Hinduism in the United States

Hinduism is a minority religion in the United States of America, constituting 1% of the population.[4] The vast majority of American Hindus are immigrants mainly from India, some from Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, and a minority from Bhutan, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Additionally, the United States has a number of converts to Hinduism.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,338,214 (2020) 1% of U.S. Population[2](2016 Public Religion Research Institute data) 1% of the U.S. Population (2015 Pew Research Center data)[3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 483,000 | |

| 278,600 | |

| 202,157 | |

| 130,110 | |

| 128,119 | |

| 78,879 | |

| 70,300 | |

| Religions | |

| Hinduism | |

| Languages | |

Majority spoken languages

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hinduism by country |

|---|

|

| Full list |

There are also Hindus from the Caribbean (mainly Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana, some from Suriname and Jamaica), Southeast Asia (mainly Singapore, Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia (especially Bali and Java), Canada, Oceania (mainly Fiji, Australia, and New Zealand), Africa (mainly Mauritius, South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Réunion, and Seychelles), Europe (mainly United Kingdom, Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and France), and the Middle East (mainly the Gulf countries), and other countries and their descendants. There are also about 900 ethnic Cham people from Vietnam, living in America, 55% of whom are Hindus.[5]

While there were isolated sojourns by Hindus in the United States during the 19th century, Hindu presence in the United States was extremely limited until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[6]

Hindu-Americans hold the highest levels of educational attainment among all religious communities in the United States. This is mostly due to strong US immigration policies that favor educated and highly skilled migrants.[7] Many concepts of Hinduism, such as meditation, karma, ayurveda, reincarnation, and yoga, have entered into mainstream American vernacular.[8] According to Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life survey of 2009, 24% of Americans believe in reincarnation, a core concept of Hinduism.[9][10] Furthermore, the Hindu values of vegetarianism and ahimsa are gaining in popularity. In September 2021, the State of New Jersey aligned with the World Hindu Council to declare October as Hindu Heritage Month. Om is a widely chanted mantra across the United States, particularly among millennials and those who practice yoga and subscribe to the New Age philosophy.

Demographics

The United States Department of State's 2004 Religious Freedom Report[11] found some 1.5 million adherents of Hinduism, corresponding to 0.50% of the total population. The Hindu population of USA is the world's eighth-largest; 10% of Asian Americans who together account for 5.8% of US population, are followers of the Hindu faith.[12]

Most Hindus in America are immigrants (87%) and 9% are the children of immigrants and 10% of the Hindus are converts.[13]The vast majority of Hindus are immigrants from South Asia (mainly India, some from Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, and a minority from Bhutan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Maldives). There are also Hindus from the Caribbean (mainly Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana, some from Suriname and Jamaica), Southeast Asia (mainly Singapore, Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia (especially Bali and Java)), Canada, Oceania (mainly Fiji, Australia, and New Zealand), Africa (mainly Mauritius, South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, Réunion, and Seychelles), Europe (mainly United Kingdom, Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and France), and the Middle East (mainly the Gulf countries), and other countries and their descendants. Additionally, the United States has number of converts to Hinduism. There are also about 900 ethnic Cham people from Vietnam, one of the few remaining non-Indic Hindus in the world, living in America, 55% of whom are Hindus.[14] In the 1990s, Buddhist Bhutan expelled or forced to leave most of its Hindu population, one-fifth of the country's population, demanding conformity in religion.[15] More than 90,000 Hindu-Bhutanese refugees have been resettled in the United States.[16]

Many of the Afghan Hindus have also settled in United States with their family, mainly after Soviet–Afghan War and rise of Taliban. Many of them immigrated to United States due to the discrimination faced by them in their homeland. Many of them reflects and influence the Culture of Afghanistan in United States.[17][18]A number of Hindu Americans are twice or thrice-migrant because they came directly from the former British colonies in Africa, the Caribbean, Fiji etc. or from East Africa via Great Britain respectively[19]

According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March 2017, Hindus were the largest minority religion in 92 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[20] In September 2021, the State of New Jersey aligned with the World Hindu Council to declare October as Hindu Heritage Month.

Although Hinduism is practiced mainly by people of South Asian descent, a sizable amount of Hindus in United States were converts to Hinduism. According to the Pew research estimates, 9% of the Hindus in United States belong to a non-Asian ethnicity – 4% of the Hindus in United States were White, 2% were Black, 1% Latino and 2% Mixed.[21] Converts to Hinduism include Hollywood actress Julia Roberts, actor Russell Brand etc.[22][23]

Contemporary status and Public Opinion

American Hindus have the highest rates of educational attainment and highest rate of household income among all religious communities, and the lowest divorce rates.[24] This is mostly due to strong US immigration policies that favor educated and highly skilled migrants only.

According to the 2008 Pew Research, Of all the America adults who said they were raised as Hindus, 80 percent continued to adhere to Hinduism which is the highest retention rate for any religion in America.[25]

Public opinions of Hindus

Hindus also have relatively high acceptance of homosexuality. 71% of the Hindus in the United States believe that homosexuality should be accepted, which is higher than the general public which is 62%.[21] About 68% of the Hindus supported same-sex marriage, while that of general public is 53%.[21] Hindus in the United States also showed high support for abortion. About 68% of the Hindus supported abortion. About 69% of the Hindus supported strict laws and regulation for the protection of environment and nature.[21]

According to the Pew Research Center, only 15% of the Americans identified the Vedas as a Hindu religious text. Roughly half of Americans knew that yoga has roots in Hinduism.[26][27] On the same survey when respondents were asked to rate how warmly they see religious groups on a "feeling thermometer"; Hindus were below Jews, Catholics, and Evangelical Christians; but were above Atheists, and Muslims. The Survey noted that on a scale of 0–100, Hindus had a thermometer reading at 55 compared to 63 for Jews, and Muslims at 49.[26][27]

Religiosity

According to a 2014 Pew Research survey, 88% of the American Hindu population believed in God (versus 89% of adults overall). However, only 26% believed that religion is very important in their life. About 51% of the Hindu population reported praying daily.[21]

Though 88% of Hindus believe in God, that is low compared to the 99% of Evangelical Protestants, 96% of Catholics, 99% of Jehovah's Witnesses, etc.[21]

History

Anandibai Joshi is believed to be the first Hindu woman to set foot on American soil, arriving in New York in June 1883 at the age of 19. She graduated with an MD from the Women's Medical College of Pennsylvania on March 11, 1886, becoming the first female of South Asian origin to graduate with a degree in Western medicine from the United States. Joshi returned to India in late 1886 but died within months of her return.[28]

One of the first major discussions of Hinduism in the United States was Swami Vivekananda's address to the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. He spent two years in the United States, and lectured in several cities including Detroit, Boston, and New York. In 1902 Swami Rama Tirtha visited the US for about two years lecturing on the philosophy of Vedanta.[29] In 1920 Paramahansa Yogananda was India's delegate at the International Congress of Religious Liberals held in Boston.[30]

Prior to 1965, Hindu immigration to the United States was minuscule and isolated, with fewer than fifty thousand Indians immigrating before 1965. It is worth noting that although most of these immigrants were Punjabi Sikhs, they were incorrectly referred to as "Hindoo" by many Americans, as well as in some official immigration documents.[31] The Bellingham Riots in Bellingham, Washington on September 5, 1907, epitomized the low tolerance in the United States for Indians and Hindus. In the 1923 case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court ruled that Thind and other South Asians were not "free white persons" according to a 1790 federal law that stated that only white immigrants could apply for naturalized citizenship.[32] The Immigration Act of 1924 prohibited the immigration of Asians such as Middle Easterners and Indians. This further prevented Hindus from immigrating to the United States.[33] Despite such events, some people, including professionals, stayed and worked until the Immigration and Nationality Services (INS) Act of 1965 was passed. This opened the doors to Hindu immigrants who wished to work and start families in the United States.[34] It included Hindu preachers as well, who spread awareness of the religion among the people who had little or no contact with it.[35]

Also during the 1960s, Hindu teachers found resonance in the US counter-culture, leading to the formation of a number of Neo-Hindu movements such as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness founded by Swami Prabhupada.[36] People involved in the counter-culture such as Ram Dass, George Harrison, and Allen Ginsberg were influential in the spread of Hinduism in the United States. Ram Dass was a Harvard professor known as Richard Alpert and after being fired from Harvard was receiving a lot of media coverage. He traveled to India and studied under Neem Karoli Baba and came back to the west as a Hindu teacher and changed his name to Ram Dass which means servant of Rama (one of the Hindu gods). A student of Ram Dass, Jeffery Kagel, devoted his life to Hinduism in the sixties and is now making many CDs chanting the sacred mantras or spiritual verses. He has been very successful and is considered the rock star of yoga. George Harrison was a member of The Beatles which in its peak of popularity was receiving more media coverage than any other band in the world.[37] He became a devotee of Swami Prabhupada. George Harrison started to record songs with the words "Hari Krishna" in the lyrics and was widely responsible for popularizing Hinduism in America with the younger generation of the time. Allen Ginsberg, the author of Howl, became a figure in the sixties that was also heavily involved with Hinduism and it was said that he chanted "Om" at The Human Be-in of 1967 for hours on end. Other influential Indians of Hindu faith are Mata Amritanandamayi, Chinmoy and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.[38]

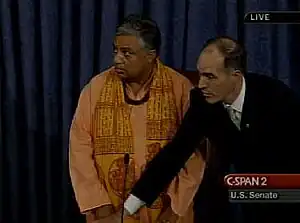

A joint session of the United States Congress was opened with a prayer in Sanskrit (with some Hindi and English added), read by Venkatachalapathi Samudrala, in September 2000, to honor the visit of Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The historic gesture was an initiative by Ohio Congressman Sherrod Brown who requested the US Congress House Chaplain to invite the Hindu priest from the Shiva Vishnu Hindu Temple in Parma, Ohio.[39] Another Hindu prayer was read in the United States Senate on July 12, 2007, by Rajan Zed, a Hindu chaplain from Nevada.[40] His prayer was interrupted by a couple and their daughter who claimed to be "Christian patriots", which prompted a criticism of candidates in the upcoming presidential election for not criticizing the remarks.[41] In October 2009, President Barack Obama lit a ceremonial Diwali lamp at the White House to symbolize victory of light over darkness. In April 2009, President Obama appointed the first Hindu American, Anju Bhargava, a management consultant and pioneer community builder, to serve as a member of his inaugural Advisory Council on Faith Based and Neighborhood Partnership. In collaboration with the White House Hindu American Seva Communities was formed to bring the Hindu seva voices to the forefront in the public arena and to bridge the gap between US government and Hindu and Dharmic people and places of worship.

As of February 2017 92,323 exiled Bhutanese refugees have been resettled in the USA since 2008. Hinduism is the major religion of Bhutanese who have settled in the USA.[42][43]

Western Influence

Hindu Americans as well as Hindu Immigrants can be seen adapting their practice and places of worship in accordance with the world around them. Many of the early Hindu emissaries to the United States drew on ideological confluences between Christian and Hindu universalism.[44] Hindu temples in the United States tend to house more than one deity corresponding with a different tradition, unlike those in India which tend to house deities from a single tradition.[45] Not only has yoga entered the American vernacular, but its meaning has shifted. While Hindus in the United States may refer to the practice as a form of meditation that has different forms (i.e. karma yoga, bhakti yoga, kriya yoga), it is used in reference to the physical aspect of the word.[46]

Life and culture

Community and social life

Hindu temples

The Vedanta Society was responsible for building the earliest temples in the United States starting in 1905, with the Old Temple in San Francisco,[47][48][49] but they were not considered formal temples.[50] The earliest traditional Mandir in the United States is Shiva Kartikeya Temple in Concord, California and was built in 1957 known as Palanisamy Temple, it is one of the few temples that is run by the public by elected members.[51] The Maha Vallabha Ganapathi Devastanam owned by the Hindu Temple Society of North America in Flushing, New York City was consecrated on July 4, 1977. This temple recently underwent significant expansion and renovation.[52]

Today there are over 1450 Hindu Temples across the United States,[53] spread across the country, with a majority of them situated on the east coast centered around the New York region which alone has over 1135 temples[54] the next largest number being in Texas with 128 Temples[55] and Massachusetts with 127 temples.[56]

Other prominent temples include the Malibu Hindu Temple, built-in 1981 and located in Calabasas, is owned and operated by the Hindu Temple Society of Southern California. The temple is near Malibu, California. Apart from these, Swaminarayan temples exist in several cities across the country with a sizable following.

The Sri Ganesha Temple of Alaska in Anchorage is the northernmost Hindu temple in the world.[57]

The oldest Hindu Temple in Texas is the Shree Raseshwari Radha Rani temple at Radha Madhav Dham, Austin.[58] The temple, established by Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj is one of the largest Hindu Temple complexes in the Western Hemisphere,[59] and the largest in North America.[60][61][62]

In Tampa, South Florida, the Sri Vishnu Temple was consecrated in November 2001.[63]

Parashakthi Temple[64] in Pontiac, Michigan is a tirtha peetham in the west for Goddess "Shakthi" referred to as the "Great Divine Mother" in Hinduism. The Temple was envisioned by Dr. G Krishna Kumar in a deep meditative kundalini experience of "Adi Shakthi" in 1994.[65]

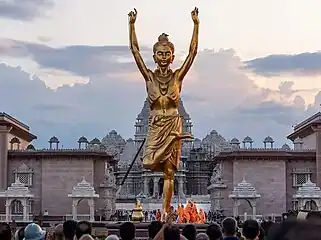

Akshardham in Robbinsville, New Jersey is one of the largest stone Hindu temples in the United States.[66]

The Indian American Cultural Center opened on March 9, 2002, in Merrillville, Northwest Indiana. It was in 2010 on June 18 that the temple was finalized and opened, The Bharatiya Temple of Northwest Indiana.[67] This temple is adjacent to the Cultural Center. In the native way of Hinduism, one would never see different sectarian groups worship in one temple. The Bharatiya Temple is unique in its own way by allowing different sectarian groups to worship together. The Bharatiya Temple has four different Hindu groups as well as a Jain group.[68]

Hindu Temple of St. Louis, Missouri

Hindu Temple of St. Louis, Missouri Sri Guruvaayoorappan Temple in Morganville, New Jersey

Sri Guruvaayoorappan Temple in Morganville, New Jersey

Political Involvement

A Hindu Military Chaplaincy was launched in May 2011; Army Captain Pratima Dharm became the first Hindu to serve as a U.S. military chaplain.[69]

Tulsi Gabbard became the first-ever Hindu to be elected to the US Congress in 2012, prior to becoming the first Hindu to seek a major party nomination for President in 2020; she is a Hawaiian of Samoan and European descent, the daughter of a Roman Catholic father and a Hindu mother.[70] Later, in 2016 three more Hindus were elected to Congress: Raja Krishnamoorthi, Pramila Jayapal and Ro Khanna (Rohit Khanna)all of Indian descent.[71] American Hindus are now the third-largest Religious Group in Congress with four members.[72] Among the lawmakers declining to state their religious affiliations were Indian-American Pramila Jayapal elected to the House of Representatives; since her mother is a Hindu, the Hindu American Foundation suggests that Jayapal is also Hindu.[73] In 2019 Padma Kuppa, an Indian politician from Troy Michigan joined the House of Representatives.

The American Hindu are considered as an important vote bank in the American Politics.[74]

Businessman Vivek Ramaswamy became the first Hindu to seek the Republican nomination for the presidency during the 2024 Republican Party presidential primaries.

Activism

Several organizations have been made to combat discrimination against Hindus in the United States and make changes in the political scene. Some of these organizations include:

- Hindu American Foundation

- Sadhana: Coalition of Progressive Hindus[75]

- CoHNA: Coalition of Hindus of North America[76]- Due to their activism the US state of Georgia passed resolution condemning Hinduphobia in 2023, making it the first state in US to pass such a resolution.[77]

- HinduPACT

Hinduism in United States Territories

U.S Virgin Islands

According to the 2000 census, there were more than 400 Hindus in the United States Virgin Islands (0.4% of the population).[79] According to the 2011 census, there are 528 Hindus in the U.S. Virgin Islands representing 1.9% of the population. The majority reside in the Tortola Island (454) followed by the Virgin Gorda Island (69).[80] Tortola and Virgin Gorda are part of the British Virgin Islands, to which these statistics refer, so are not applicable here. The majority of them are Sindhi Hindus and Indo-Caribbeans with some Gujaratis.[79] There is a Hindu temple in La Grande Princesse, St. Croix and one in Frenchman's Bay, St. Thomas.[81][82]

Puerto Rico

As of 2006, there were 3,482 Hindus in Puerto Rico making up 0.09% of the population, according to Religious Intelligence.[83]

Discrimination

Temple desecration

In January 2019, Swaminarayan Temple in Kentucky was vandalized. They sprayed black paint on the deity and also sprayed 'Jesus is the only God' on the walls. The Christian cross was also spray painted on various walls.[84][85] In February 2015, Hindu temples in Kent and the Seattle Metropolitan area were vandalized, and in April 2015, a Hindu temple in north Texas was vandalized with xenophobic images spray-painted on its walls.[86][87] The Sri Venkateshwara temple in Pittsburgh was also vandalized and $15000 worth of jewelry was stolen.[88]

In January 2023, the Shri Omkarnath Temple located in Brazos Valley, Texas was broken into by the burglars. The board member of temple, Srinivasa Sunkari said "There was a sense of invasion, that sense of loss of privacy when something like this happened to us". Hindu advocacy organizations like HinduPact and Hindu American Foundation demanded investigation in the issue.[89]

Venkatachalapathi Samuldrala

The first Hindu opening prayer offered in the U.S. Congress was by Venkatachalapathi Samuldrala, a priest of Shiva Hindu Temple in Parma, Ohio.[90][91][92][93] This prompted criticism from the Family Research Council (FRC), a conservative Christian group, who protested against it in conservative media, in turn generating responses from their opponents and leading to serious discussions over the role of legislative chaplains in a pluralist society.[92]

Rajan Zed

There was controversy over the prayer by Rajan Zed, a Hindu cleric, in United States Senate.[94] It was instigated by the conservative Christian group American Family Association, which cited the loss of the "Judeo-Christian foundations" of the United States as a motive.[95]

California textbook protest over Hindu history

A controversy in the US state of California concerning the portrayal of Hinduism in history textbooks began in 2005. The Texas-based Vedic Foundation and the American Hindu Education Foundation complained to California's Curriculum Commission, arguing that the coverage in sixth grade history textbooks of Indian history and Hinduism was biased against Hinduism.[96] Points of contention included a textbook's portrayal of the caste system, the Indo-Aryan migration theory, and the status of women in Indian society.[97]

See also

- Hinduism in the Philippines

- Maharishi Vedic City, Iowa

- Hindu American Foundation

- Hindu Temple Society of North America

- Hindu University of America

- Hinduism in Los Angeles

- Sanskrit studies

- Hinduism Today

- Indians in the New York City metropolitan area

- List of Hindu temples in the United States

- Hindu eschatology

- Hinduism in Vietnam

- Micheal Altman

References

- "hindus in the United States of America". worldatlas.com. August 16, 2017.

- Cox, Daniel; Jones, Ribert P. (June 9, 2017). America's Changing Religious Identity.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center. May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- "About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated". Measuring Religion in Pew Research Center's American Trends Panel. Pew Research Center. December 14, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- "Eastern Cham in the United States". Joshua Project.net. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Batalova, Jeanne Batalova Mary Hanna and Jeanne (October 15, 2020). "Indian Immigrants in the United States". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- Hilburn, Matthew (July 30, 2012). "Hindu-Americans Rank Top in Education, Income". Voice of America. Archived from the original on February 20, 2013. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- Rajghatta, Chidanand (August 18, 2009). "Americans turn to Hindu beliefs". The Times of India. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- Ryan, Thomas (October 21, 2015). "25 percent of US Christians believe in reincarnation. What's wrong with this picture?". America. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- Miller, Lisa (August 15, 2009). "We Are All Hindus Now". Newsweek. Retrieved July 11, 2018 – via AdiShakti.org.

- "International Religious Freedom Report". United States Department of State. 2004.

- "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research Center. July 19, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- "Hindu population up in US, becomes fourth-largest faith". India Today. Indo-Asian News Service. May 13, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Eastern Cham in the United States". Joshua Project.net. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Bhutan: International Religious Freedom Report". United States Department of State. 2007.

- "90,000th Bhutanese refugee flying to US from Nepal for resettlement". The Himalayan Times. September 20, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "First Afghan Hindu and Sikh Temple in Maryland a Cultural Bridge | Voice of America - English". www.voanews.com. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: Afghan". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Rangaswamy, Padma (2007). Indian Americans (2007 Hardcover ed.). New York: Chelsea House. p. 55. ISBN 9780791087862.

gujarati.

- "Largest Non-Christian Faith Tradition by County" (PDF). Religion Census Newsletter. Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. March 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "I'm a Hindu: Julia Roberts - Times of India". The Times of India. August 7, 2010. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Tatchell, Lucy (October 23, 2010). "Katy Perry and Russell Brand are married in private Hindu ceremony". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Rajagopal 2005, p. 2.

- "Hindus - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- "Only 15% Americans identify Vedas as Hindu religious text". City Air News. July 24, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Alper, Becka A. (July 23, 2019). "6 facts about what Americans know about religion". Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Historical Photos Depict Women Medical Pioneers". Public Radio International. July 12, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Arora, Raj Kumar (1978). Swami Ram Tirath, his life and works. New Delhi, India: Rajesh Publications. p. 56.

- Hevesi, Dennis (December 3, 2010). "Sri Daya Mata, Guiding Light for U.S. Hindus, Dies at 96 (Published 2010)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- Chan, Sucheng (1991). Asian Americans: An Interpretive History. Boston, Mass.: Twayne. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-80578-426-8.

- Coulson, Doug (2015). "British Imperialism, the Indian Independence Movement, and the Racial Eligibility Provisions of the Naturalization Act: United States v. Thind Revisited". Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives. 7: 1–42. SSRN 2610266.

- Mann, Gurinder Singh; Numrich, Paul David & Williams, Raymond Brady (2001). Buddhists, Hindus and Sikhs in America: A Short History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-19512-442-2.

- Lee, Erika (October 1, 2015). "Legacies of the 1965 Immigration Act". South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA). Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- Bagoria, Mukesh (2009). "Tracing the Historical Migration of Indians to the United States". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 70: 894–904. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44147737.

- "Srila Prabhupada Lila". www.srilaprabhupadalila.org. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- Williams, John P. (September 11, 2019). "Journey to America: South Asian Diaspora Migration to the United States (1965–2015)". Indigenous, Aboriginal, Fugitive and Ethnic Groups Around the Globe. doi:10.5772/intechopen.88118. ISBN 978-1-78985-431-2.

- "Proud to be 1st Hindu-American to run for president: Tulsi Gabbard". The Economic Times. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- "For the first time, a Hindu priest will pray before US Congress". Rediff.com. September 14, 2000. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "California Senate opened with Hindu prayer for first time". Asian Tribune. August 29, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- Boorstein, Michelle (July 27, 2007). "Hindu Groups Ask '08 Hopefuls to Criticize Protest". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Maxym, Maya (March 1, 2010). "Nepali-speaking Bhutanese (Lhotsampa) Cultural Profile". Ethnomed.org. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- Koirala, Keshav P. (February 6, 2017). "Where in US and elsewhere Bhutanese refugees from Nepal resettled". The Himalayan Times. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Lucia, Amanda (January 25, 2017). "Hinduism in America". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.436. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Prema, Kurien A. (2006). "Multiculturalism and "American" Religion: The Case of Hindu Indian Americans". Social Forces. 85 (2): 723–741. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0015. S2CID 146134214. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- Lucia, Amanda (January 25, 2017). "Hinduism in America". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.436. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- "Week a fitting time to celebrate East Indians' success in SF". November 3, 2018.

- "Visit to Vedanta Society and the Old Temple of 1905 | Society for Asian Art".

- "Old Temple | Vedanta Society of Northern California". December 30, 2020.

- Sen, Arijit (2013). Staged Disappointment - Interpreting the Architectural Facade of the Vedanta Temple, San Francisco. Vol. 47. pp. 207–214. doi:10.1086/673870. S2CID 164182046.

- "Hinduism in America". The Pluralism Project. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- "Ganesh Temple History". NY Ganesh Temple.org. October 28, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Iyer, Hari. "Global Hindu Temples directory ~ America". All Hindu Temples. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- Iyer, Hari. "Global Hindu Temples directory ~ New York". All Hindu Temples. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- Iyer, Hari. "Global Hindu Temples directory ~ Texas". All Hindu Temples. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- Iyer, Hari. "Global Hindu Temples directory ~ Massachusetts". All Hindu Temples. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- "Sri Ganesth Temple of Alaska Timings and Address". templesinindiainfo. April 10, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- India Today International. Volume 1, Issues 1–8. Living Media International. 2002.

- "Vedic Foundation Inaugurated at Barsana Dham, Austin" (PDF). Hindu University of America Newsletter. 12 (2): 2. July 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 18, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Ciment, James, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of American Immigration. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-76568-028-0.

- Hylton, Hilary; Rossie, Cam (2004). Insiders' Guide to Austin (4th ed.). Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-0-76272-997-5.

- Mugno, Marjie; Rafferty, R. R., eds. (1998). Texas Monthly Guidebook. Houston, Texas: Gulf Pub. Co.

- "South Florida Hindu Temple - Welcome to the Temple Experience !!!". www.sfht.org. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- "Shakthi Worship". Parashakthi Temple. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Honoring the eternal Divine Mother". India Abroad. December 30, 2011. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- Kuruvilla, Carol (August 26, 2014). "PHOTOS: Stunning Hindu temple in New Jersey is one of the largest in America". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014.

- "Bharatiya Temple of NWI". www.bharatiyatemple-nwindiana.org. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- Pati, George (2011). "Temple and Human Bodies: Representing Hinduism". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 15 (2): 191–207. doi:10.1007/s11407-011-9103-x. S2CID 145472191. ProQuest 904024803.

- Chaudhary, Ravi (June 6, 2011). "Launching The First Hindu Military Chaplaincy". Huffington Post. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Basu, Tanya (March 5, 2015). "Hindus Are Thriving in America, but There's Only One in Congress". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- George, Varghese K. (January 5, 2017). "More Hindus and Buddhists in U.S. Congress: Pew study". The Hindu. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Foundation, Hindu American. "Hindu American Foundation Announces Launch Of "I Am Hindu American" Campaign". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- "Hindus and Jews gain ground in new US Congress". The Times of India. January 5, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Salman, Safiya Ghori-Ahmad, Fatima (October 21, 2020). "Why Indian Americans Matter in U.S. Politics". Foreign Policy. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Our Mission, Vision, Values". Sadhana. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- "Coalition of Hindus of North America". CoHNA. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- AP (April 1, 2023). "Georgia passes resolution condemning Hinduphobia". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- Crabtree, Vexen. "Guam (Territory of Guam)". The Human Truth Foundation. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Faith Matters: Hinduism in the U.S.V.I." The St. Croix Source. July 11, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Demographics census in VGB" (PDF). data census.in.

- "Faith Matters: Hinduism in the U.S.V.I." July 11, 2011. Archived from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- Shree Ram Naya Sabha, Inc. v. Hendricks, 19 VI 216 (D.V.I. July 14, 1982).

- Tharoor, Kanishk (October 9, 2015). "Small places, new countries". @businessline. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- "In New "Hate Crime" Incident, Hindu Temple Vandalised In US' Kentucky". NDTV.com. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- "Hindu temple vandalized with hate speech in US, hateful words written on walls". Times Now News. January 31, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Hindu temple vandalised in U.S." The Hindu. January 31, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Chatterjee, Pallabi (January 31, 2019). "US: Hindu temple vandalized in Kentucky, deity sprayed black paint". Yahoo! News India. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Police Investigate Robbery At Hindu Temple". www.cbsnews.com. March 17, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- "US; Burglars break into Texas Hindu temple, steal donation box: Report". gulfnews.com. January 20, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- Congressional Record, Proceedings and Debates of the 106th Congress, Second Session. Vol. 146. September 14, 2000. p. 18005 (H7579).

- Robinson, B.A. (September 28, 2000). "Hindu Invocation In Congress". ReligiousTolerance.org. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- "Congress' Hindu Blessing". Hinduism Today. January 2001. Archived from the original on May 11, 2003.

- Marty, Martin E. (October 26, 2000). "Spiritual Adultery?". The Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion. University of Chicago Divinity School. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Davies, Haley (August 27, 2007). "Hindu chaplain Rajan Zed leads state Senate in opening prayer". SFGATE. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Boorstein, Michelle (July 27, 2007). "Hindu Groups Ask '08 Hopefuls to Criticize Protest". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "Textbook Reform Initiative: Problem statement". Vedic Foundation. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- Vashisht, Kanupriya (January 11, 2006). "The Hindutva deluge in California". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2006.

Further reading

- Bhatia, Sunil (August 1, 2007). American Karma: Race, Culture, and Identity in the Indian Diaspora. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-0919-1.

- Kurien, Prema (2012). "Chapter 7. What is American about American Hinduism? Hindu Umbrella Organisations in the United States on Comparative Perspective". In Zavos, John; et al. (eds.). Public Hinduisms. New Delhi: SAGE Publ. India. ISBN 978-81-321-1696-7.

- Rajagopal, Arvind (2005). "Hindu Diaspora in the United States". In Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (eds.). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Boston, Ma: Springer US. pp. 445–454. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-29904-4_45. ISBN 978-0-387-29904-4.

- "Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

.jpg.webp)