HIV/AIDS in India

HIV/AIDS in India is an epidemic. The National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) estimated that 2.14 million people lived with HIV/AIDS in India in 2017.[1] Despite being home to the world's third-largest population of persons with HIV/AIDS (as of 2018, with South Africa and Nigeria having more),[2] the AIDS prevalence rate in India is lower than that of many other countries. In 2016, India's AIDS prevalence rate stood at approximately 0.30%—the 80th highest in the world.[3] Treatment of HIV/AIDS is primarily via a "drug cocktail" of antiretroviral drugs and education programs to help people avoid infection.

Epidemiology

The main factors which have contributed to India's large HIV-infected population are extensive labour migration and low literacy levels in certain rural areas resulting in a lack of awareness and in gender disparities.[4] The Government of India has also raised concerns about the role of intravenous drug use and prostitution in spreading HIV.[4][5]

According to Avert,[6] the statistics for special populations in 2007 are as follows:

| State | Antenatal clinic HIV prevalence 2007 (%)[7] | STD clinic HIV prevalence 2007 (%)[6] | IDU HIV prevalence 2007 (%)[6] | MSM HIV prevalence 2007 (%)[6] | Female sex worker HIV prevalence 2007 (%)[6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A & N Islands | 0.25 | 8.00 | 16.80 | 6.60 | 4.68 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 1.00 | 17.20 | 3.71 | 17.04 | 9.74 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ... | ... |

| Assam | 0.00 | 0.50 | 2.41 | 2.78 | 0.44 |

| Bihar | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 3.41 |

| Chandigarh | 0.25 | 0.42 | 8.64 | 3.60 | 0.40 |

| Chhattisgarh | 0.25 | 3.33 | ... | ... | 1.43 |

| D & N Haveli | 0.50 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Daman & Diu | 0.13 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Delhi | 0.25 | 5.20 | 10.10 | 11.73 | 3.15 |

| Goa | 0.18 | 5.60 | ... | 7.93 | ... |

| Gujarat | 0.25 | 2.40 | ... | 8.40 | 6.53 |

| Haryana | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 5.39 | 0.91 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0.00 | 0.00 | ... | 5.39 | 0.87 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 0.00 | 0.20 | ... | ... | ... |

| Jharkhand | 0.00 | 0.40 | ... | ... | 1.09 |

| Karnataka | 0.50 | 8.40 | 2.00 | 17.60 | 5.30 |

| Kerala | 0.38 | 1.60 | 7.85 | 0.96 | 0.87 |

| Lakshadweep | 0.00 | 0.00 | ... | ... | 0.00 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 0.00 | 1.72 | ... | ... | 0.67 |

| Maharashtra | 0.50 | 11.62 | 24.40 | 11.80 | 17.91 |

| Manipur | 0.75 | 4.08 | 17.90 | 16.4 | 13.07 |

| Meghalaya | 0.00 | 2.21 | 4.17 | ... | ... |

| Mizoram | 0.75 | 7.13 | 7.53 | ... | 7.20 |

| Nagaland | 0.60 | 3.42 | 1.91 | ... | 8.91 |

| Orissa | 0.00 | 1.60 | 7.33 | 7.37 | 0.80 |

| Pondicherry | 0.00 | 3.22 | ... | 2.00 | 1.30 |

| Punjab | 0.00 | 1.60 | 13.79 | 1.22 | 0.65 |

| Rajasthan | 0.13 | 2.00 | ... | ... | 4.16 |

| Sikkim | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.47 | ... | 0.00 |

| Tamil Nadu | 0.25 | 1.33 | ... | ... | ... |

| Tripura | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.00 | ... | ... |

| Uttar Pradesh | 0.00 | 0.48 | 1.29 | 0.40 | 0.78 |

| Uttaranchal | 0.00 | 0.00 | ... | ... | ... |

| West Bengal | 0.00 | 0.80 | 7.76 | 5.61 | 5.92 |

Note: Some areas in the above table report an HIV prevalence rate of zero in antenatal clinics. This does not necessarily mean HIV is absent from the area, as some states report the presence of the virus at STD clinics and among intravenous drug users. In some states and union territories, the average antenatal HIV prevalence is based on reports from only a small number of clinics.

In India, populations which are at a higher risk of HIV are female sex workers, men who have sex with men, injecting drug users, and transgenders/hijras.[8]

Management

India has been praised for its extensive anti-AIDS campaigning.[9] According to Michel Sidibé, executive director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), India's success comes from using an evidence-informed and human rights-based approach that is backed by sustained political leadership and civil society engagement.[10]

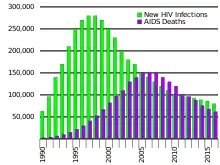

A 2012 UNAIDS report lauded India for doing "particularly well" in halving the number of adults newly infected between 2000 and 2009 in contrast to some smaller countries in Asia. In India, the number of deaths due to AIDS stood at 170,000 in 2009. It also points out that India provided substantial support to neighbouring countries and other Asian countries – in 2011, it allocated USD 430 million to 68 projects in Bhutan across key socioeconomic sectors, including health, education and capacity building. In 2011 at Addis Ababa, the Government of India further committed to accelerating technology transfer between its pharmaceutical sector and African manufacturers.

The National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) has increased the number of centres providing free antiretroviral treatment (ART) from 54 to 91 centres, with 9 more centres to be operational soon. Medicines for treating 8,500 patients have been made available at these centres. All the 91 centres have trained doctors, counsellors and laboratory technicians to help initiate patients on ART and provide follow up care while protecting confidentiality. Apart from providing free treatment, all the ART centres provide counselling to the infected persons so that they regularly take their medication. Continuity is the most important factor for the long term effectiveness of the ART drugs, as disruption can lead to drug resistance. At present, 40,000 are on ART, which is expected to go up to 85,000 by March.

Responding to a petition made by NGO's, in 2010, the Supreme Court of India directed the Indian government to provide second-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) to all AIDS patients in the country, and warned the government against abdicating its constitutional duty of providing treatment to HIV positive patients on grounds of financial constraint, as it was an issue of the right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Previously, in an affidavit before the Supreme Court, NACO said second-line ART treatment for HIV patients, costing Rs 28,500 each, could not be extended to those who had received "irrational treatment" by private medical practitioners for the first round, which costs around Rs 6,500. The court rejected both the arguments of financial constraints and that only 10 viral load testing centres were needed for testing patients for migrating from the first line of treatment to the second line, as stated by the Solicitor General representing the government. The court further asked the government to give a clear-cut and "workable" solution within a week's time.[11][12]

HIV spending increased in India from 2003 to 2007 and fell by 15% in 2008 to 2009. Currently, India spends about 5% of its health budget on HIV/AIDS. Spending on HIV/AIDS may create a burden in the health sector, which faces a variety of other challenges. Thus, it is crucial for India to step up on its prevention efforts to decrease its spending of the health budget on HIV/AIDS in future.[6]

Apart from government funding, there are various international foundations like the UNDP, World Bank, Elton John AIDS Foundation, USAID and others who are funding HIV/AIDS treatment in India.[13][14][15]

History

In 1986, the first known cases of HIV in India were diagnosed by Dr. Suniti Solomon and her student Dr. Sellappan Nirmala amongst six female sex workers in Chennai, Tamil Nadu.[16][17] But actually in 1980 's Sellappan nirmala visited Dr.Kandaraj, Sexologist, Chennai. He collected the 30 no of blood samples of HIV disease, patients for nirmala. All the patients were sex workers. After the samples are submitted to Dr.Suniti solomon. She was a microbiologist. She diagnosed with all samples are HIV positive cases and announced by her proper report to Indian government. 30 HIV patients were affected in India.

In the year of 1986, the Government of India established the National AIDS Committee within the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.[18]

In 1992, on the basis of National AIDS Committee, the government set up the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) to oversee policies and prevention and control programmes relating to HIV and AIDS and the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) for HIV prevention.[19][20] Subsequently, the State AIDS Control Societies (SACS) were set up in states and union territories. SACS implement the NACO programme at a state level, but have functional independence to upscale and innovate.[21] The first phase was implemented from 1992 to 1999 and focused on monitoring HIV infection rates among high-risk populations in selected urban areas.[18]

In 1999, the second phase of the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP II) was introduced to decrease the reach of HIV by promoting behaviour change. The prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme (PMTCT) and the provision of antiretroviral treatment were developed.[22] A National Council on AIDS was formed during this phase, consisting of 31 ministries and chaired by the Prime Minister.[18] The second phase ran between 1999 and 2006.[18]

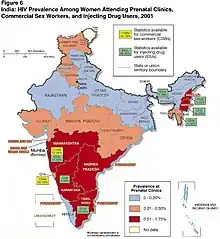

A 2006 study published in the British medical journal The Lancet reported an approximately 30% decline in HIV infections from 2000 to 2004 among women aged 15 to 24 attending prenatal clinics in selected southern states of India, where the epidemic is thought to be concentrated. Recent studies suggest that many married women in India, despite practicing monogamy and having no risk behaviours, acquire HIV from their husbands and HIV testing of married males can be an effective HIV prevention strategy for the general population.[23]

In 2007, the third phase of the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP III) targeted high-risk groups and conducted outreach programmes. It also decentralised the effort to local levels and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to provide welfare services to the affected.[6] The US$2.5 billion plan received support from UNAIDS.[24] The third stage dramatically increased targeted interventions, aiming to halt and reverse the epidemic by integrating programmes for prevention, care, support and treatment.[18] By the end of 2008, targeted interventions covered almost 932,000 of those most at risk, or 52% of the target groups (49% of female sex workers, 65% of injection drug users and 66% of men who have sex with men).[18]

Some efforts have been made to tailor educational literature to those with low literacy levels, mainly through readily accessible local libraries.[25] Increased awareness regarding the disease and citizen's related rights is in line with the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

In 2009, India established a National HIV and AIDS Policy and the World of Work, which sought to end discrimination against workers on the basis of their real or perceived HIV status.[18] Under this policy, all enterprises are encouraged to establish workplace policies and programmes based on the principles of non-discrimination, gender equity, healthy work environment, non-screening for the purpose of employment, confidentiality, prevention and care and support.[18] Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute have called for greater attention to migrant workers, whose concerns about their immigration status may leave them particularly vulnerable.[18]

No agency is tasked with enforcing the non-discrimination policy; instead, a multisectoral approach has been developed involving awareness campaigns in the private sector. The AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (AIDS Anti-Discrimination Movement) has prepared many citizen reports challenging discriminatory policies, and filed a petition in the Delhi High Court regarding the proposed segregation of gay men in prisons. A play titled High Fidelity Transmission by Rajesh Talwar[26] focused on discrimination, the importance of using a condom and illegal testing of vaccines.[27] HIV/AIDS-related television shows and movies have appeared in the past few years, mostly in an effort to appeal to the middle class.[28] An important component of these programs has been the depiction of HIV/AIDS affected persons interacting with non-infected persons in everyday life.[29]

As per the UNDP's 2010 report, India had 2.395 million people living with HIV at the end of 2009, up from 2.27 million in 2008. Adult prevalence also rose from 0.29% in 2008 to 0.31% in 2009.[30] Setting up HIV screening centres was the first step taken by the government to screen its citizens and the blood bank.

Adult HIV prevalence in India declined from an estimated 0.41% in 2000 to 0.31% in 2009. Adult HIV prevalence at a national level has declined notably in many states, but variations still exist across the states. A decreasing trend is also evident in HIV prevalence among people aged 15–24.

A 2012 report described a need for youth HIV counseling.[31]

According to NACO data, India has had a 57% reduction in estimated annual new adult HIV infections, from 274,000 in 2000 to 116,000 in 2011, and the estimated number of people living with HIV was 2.08 million in 2011.[32][33]

According to NACO, the prevalence of AIDS in India in 2015 was 0.26%, down from 0.41% in 2002;[34] in 2016, it had risen to 0.30%.[3]

Society and culture

HIV/AIDS (Prevention and Control) Bill 2014

The HIV/AIDS (Prevention and Control) Bill 2014, which sought to end stigma and discrimination against HIV positive persons in workplaces, hospitals and society while also ensuring patient privacy, was introduced in the Rajya Sabha on 11 February 2014,[35][36] and was passed on 21 March 2017.[37]

Litigation for right of access to treatment

Orphans

There are 2 million children in India that have lost one or both parents due to AIDS.[42] There are also millions of vulnerable children living in India, or children "whose survival, well-being, or development is threatened due to the possibility of exposure to HIV/AIDS,"[42] and the number of these AIDS orphans will continue to grow.[43]

Due to the negative treatment and lack of resources for these children, AIDS orphans and vulnerable children in India are at risk for health and educational disparities. They are also at higher risk for becoming infected with HIV themselves, child labour, trafficking, and prostitution.[44]

Stigma

AIDS orphans are usually cared for by extended family members.[45] These extended family members may be vulnerable as well, as they are often elderly or ill themselves. A study from 2004 found that many AIDS orphans felt that "their guardians felt like they could demand anything of them"[46] because no one else could take them in. These children may be forced to look after a sibling or other family members, so they live in their original home even after parents are deceased. The children may be worried about seizure of land by landlords or neighbours.[47]

Due to the stigma surrounding HIV in India, children of HIV-infected parents are treated poorly and often do not have access to basic resources. A study done by the Department of Rural Management in Jharkhand showed that 35% of children of HIV-infected adults were denied basic amenities.[42] Things like proper food are often not given to AIDS orphans by their extended families or caretakers.[47] This, combined with the abuse that many orphans face, leads to a higher rate of mortality among AIDS orphans.[48] Higher education rates in caregivers has been shown to decrease this stigma.[49] AIDS orphans are often not allowed in orphanages because of the concern that they could have AIDS themselves.[50]

AIDS orphans were more likely to be bullied by friends or relatives due to the stigma against HIV/AIDS in India.[51] People may falsely believe HIV can be contracted by proximity, so these orphans can lose friends.[52] Often, women widowed by HIV/AIDS face blame for the impact on their children,[53] while families face isolation during the time of illness and after. Parents often lose their jobs due to workplace discrimination.[54] The Human Rights Watch has found many cases of sexual abuse among female AIDS orphans, which often result in trafficking and prostitution.[46] Studies have shown that an increase in quality HIV treatment and care can drastically decrease this discrimination.[49]

Mental health

The emotional and social effects on AIDS orphans are very detrimental to their health and future life. Specifically, the mental health of AIDS orphans in India is shown to be worse than that for children who were orphaned for other reasons.[51]

Before becoming orphans, children of people with AIDS face many obstacles. There is "tremendous emotional trauma" associated with having a parent ill with HIV, and the child often worries about resource scarcity, being separated from siblings, and grief over the impending death of the parent.[54] While a parent is ill, a child may experience long periods of uncertainty and episodic crises, which decreases the child's sense of security and stability.[55]

A study done in orphanages in Hyderabad showed that orphans in India who have lost one or both parents to AIDS are 1.3 times as likely to be clinically depressed as children orphaned due to other reasons.[51] In addition, the study showed greater depression among younger AIDS orphans, while in other orphans it was mostly seen in older children. A distinction was also made between genders; girls orphaned due to AIDS had a higher rate of depression than boys.[44]

Education

Because orphans and vulnerable children affected by HIV/AIDS often have many deceased or ill family members, they are often forced into taking jobs at a young age to provide for their family, resulting in lower attendance at school or being forced to drop out of school completely. For example, orphans that have lost their father due to AIDS are often forced to take on high-risk field or manual labour jobs. Orphans that have lost their mothers take on housework and childcare. Girls are more often taken out of school to help with domestic work and care for sick parents.[50] Studies show that 17% of children with HIV-infected parents took on a job to assist with household income.[42]

The cost of treatment for HIV is so high that many families often do not have the means to pay for the care or education of the child.[48] If a child is forced to drop out of school in order to take on additional responsibility at home due to the illness of his parent, the child is named a "de facto" orphan.[42] There has been no correlation found between gender and risk of poor educational outcomes or risk of dropping out of school.[56] Because of stigma, many HIV/AIDS affected orphans are expelled from school.[50]

In a study on the education of orphans in India, the caretaker's health was found to be very important in determining if the orphan was at a target educational standard.[56] When a primary caregiver was in poor health, the odds of the orphan being in the target grade level decreased by 54%.[56]

Responses

While much research has gone into community programming for AIDS orphans, only a few efforts focus on saving the lives of the HIV-infected parents themselves.[57]

When comparing institution-based care and community-based care, studies have shown that there is less discrimination in the former.[49] However, the government of India has used institutionalizing orphans as the norm, and have not fully explored other options like fostering or community-based care for AIDS orphans.[50]

India pledged to provide better resources for AIDS orphans at the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS in 2001.[47] In 2007, India was the first country in South Asia to create a national response to children affected by AIDS.[58] India created the Policy Framework For Children, which has the goal of providing resources for at least 80% of children affected by HIV/AIDS. This policy takes a rights-based approach. However, this policy fails to address many social determinants of care of AIDS orphans, including the social stigma and discrimination, lack of education, and proper nutrition.[42]

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act of 2015 was created to provide orphans and vulnerable children in India with necessary resources and care.

See also

Lists of ART centres

These centres provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) to the patients.

Non-governmental organisations

These are NGOs working in India for the prevention of HIV/AIDS and accessibility of treatment and medication. These centres also provide psycho-social support through counseling, acting to function as a bridge between hospital and home care.

- Aarogya[59]

- Ashraya

- End Aids India[60]

- Humsafar Trust

- India HIV/AIDS Alliance

- Naz Foundation (India) Trust

- SAATHII[61]

- Samapathik Trust[62]

- Sankalp Rehabilitation Trust

- Suraksha Clinic

- YRG Care

- Udaan Trust

References

- "NACO Annual Report 2018-2019" (PDF).

- "Country comparison: people living with HIV/AIDS". The World Factbook—Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Country comparison HIV/AIDS prevalence". The World Factbook—Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Source of Infections in AIDS cases in India". Embassy of India. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- "Report" (PDF). www.nacoonline.org. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- "HIV and AIDS in India". Avert. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- "HIV and AIDS in India". avert.org. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "HIV cases in India drop more than 50% but challenges remain". Hindustan Times. 19 January 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Clinton lauds India Aids campaign". BBC News. 26 May 2005. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "HIV declining in India; New infections reduced by 50% from 2000–2009; Sustained focus on prevention required" (PDF). Government of India, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Department of AIDS Control, National AIDS Control Organisation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2011.

- "SC forces govt to agree to second-line ART to all AIDS patients". The Times of India. 11 December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

- "SC cautions govt over HIV treatment". Hindustan Times. 11 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013.

- "Grants – Elton John AIDS Foundation". Elton John AIDS Foundation. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Funds and Expenditures | National AIDS Control Organization | MoHFW | GoI". naco.gov.in. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "USAID, AMCHAM join hands to address India's development challenges – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Sternberg, Steve (23 February 2005). "HIV scars India". USA Today.

- Pandey, Geeta (30 August 2016). "The woman who discovered India's first HIV cases". BBC News. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Samuels, Fiona; Wagle, Sanju (June 2011). "Population mobility and HIV and AIDS: review of laws, policies and treaties between Bangladesh, Nepal and India". Overseas Development Institute. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- "About Us | National AIDS Control Organization | MoHFW | GoI". naco.gov.in.

- "The next battleground: AIDS in India". 10 October 1993.

- "SACS | National AIDS Control Organization | MoHFW | GoI". naco.gov.in.

- Kadri, AM; Kumar, Pradeep (June 2012). "Institutionalization of the NACP and Way Ahead". Indian J Community Med. 27 (2): 83–88. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.96088. PMC 3361806. PMID 22654280.

- Das, Aritra; Babu, Giridhara R.; Ghosh, Puspen; Mahapatra, Tanmay; Malmgren, Roberta; Detels, Roger (1 December 2013). "Epidemiologic correlates of willingness to be tested for HIV and prior testing among married men in India". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 24 (12): 957–968. doi:10.1177/0956462413488568. PMC 5568248. PMID 23970619.

- "India: Driving forward an effective AIDS response". unaids.org. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Ghosh, Maitrayee 2007 ICT and AIDS Literacy: A Challenge for Information Professionals in India. Electronic Library & Information Systems 41(2):134–147

- Needle, Chael. "High Fidelity Transmission: Review – A&U Magazine".

- "HIV/AIDS: Closing the Legacy". lilainteractions.in. 28 November 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Pathak, Prachee 2005 "Sterling Towers": A Soap Opera for HIV Awareness Among the Middle Class in Urban India. Dissertations and Theses 2005.

- Bourgault, Louise M. 2009 AIDS Messages in Three AIDS-Themed Indian Movies: Eroding AIDS-Related Stigma in India and Beyond. Critical Arts: A South-North Journal of Cultural & Media Studies 23(2):171–189.

- "Health care fails to reach migrants". Hindustan Times. 1 December 2010. Archived from the original on 17 December 2010.

- Mothi, SN; Swamy, VH; Lala, MM; Karpagam, S; Gangakhedkar, RR (December 2012). "Adolescents living with HIV in India - the clock is ticking". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 79 (12): 1642–7. doi:10.1007/s12098-012-0902-x. PMID 23150229. S2CID 2346814.

- "World AIDS Day: India records sharp drop in number of cases". ndtv.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "India sees 50% decline in new hiv infections: un report". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- "World AIDS Day: India records sharp drop in number of cases". ndtv.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "HIV/Aids bill tabled in Rajya Sabha". Deccan Herald. 12 February 2014.

- "Bill to end HIV/AIDS discrimination introduced in Rajya Sabha". Zee News. 11 February 2014.

- Mishra, Nikita (December 2016). "Decoded: The Good and Bad of the HIV Bill Passed by Rajya Sabha". www.thequint.com. The Quint. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- Writ Petition (Civil) No. 311 of 2003, Supreme Court of India

- Writ Petition (Civil) No. 8700 of 2006, High Court of Delhi

- Writ Petition (Civil) No. 7 of 2005, Gauhati High Court

- Writ Petition (Civil) No. 2885 of 2007, High Court of Delhi

- Kumar, Anant (29 March 2012). "AIDS Orphans and Vulnerable Children in India: Problems, Prospects, and Concerns". Social Work in Public Health. 27 (3): 205–212. doi:10.1080/19371918.2010.525136. PMID 22486426. S2CID 40952372.

- Shetty, Avinash (January 2003). "Children orphaned by AIDS: A global perspective". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 14 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1053/spid.2003.127214. PMID 12748919.

- "An In-depth Study of Psychological Distress among Orphan Children Living in Institutional Care in New Delhi and their Coping Mechanisms". IUSSP – 2017 International Population Conference. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Gilborn, Laelia Zoe (January 2002). "The effects of HIV infection and AIDS on children in Africa". Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (1): 12–14. doi:10.1136/ewjm.176.1.12. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1071640. PMID 11788529.

- Csete, Joanne (1 June 2004). "Missed Opportunities: Human rights and the politics of HIV/AIDS". Development. 47 (2): 83–90. doi:10.1057/palgrave.development.1100033. ISSN 1461-7072. S2CID 86386789.

- Ghanashyam, Bharathi (30 January 2010). "India failing children orphaned by AIDS". The Lancet. 375 (9712): 363–364. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60151-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 20135747. S2CID 26411019.

- Mukiza-Gapere, Jackson; Ntozi, James P. M. (1995). "Care for AIDS orphans in Uganda: findings from focus group discussions". Health Transition Review.

- Messer, Lynne C.; Pence, Brian W.; Whetten, Kathryn; Whetten, Rachel; Thielman, Nathan; O'Donnell, Karen; Ostermann, Jan (19 August 2010). "Prevalence and predictors of HIV-related stigma among institutional- and community-based caregivers of orphans and vulnerable children living in five less-wealthy countries". BMC Public Health. 10 (1): 504. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-504. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 2936424. PMID 20723246.

- "Future Forsaken | Abuses Against Children Affected by HIV/AIDS in India". Human Rights Watch. 28 July 2004. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Kumar, SG Prem; Dandona, Rakhi; Kumar, G. Anil; Ramgopal, SP; Dandona, Lalit (8 April 2014). "Depression among AIDS-orphaned children higher than among other orphaned children in southern India". International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 8 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-8-13. PMC 4016624. PMID 24708649.

- Salaam, Tiaji (11 February 2005). "AIDS Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC): Problems, Responses, and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- Van Hollen, Cecilia (1 December 2010). "HIV/AIDS and the Gendering of Stigma in Tamil Nadu, South India". Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 34 (4): 633–657. doi:10.1007/s11013-010-9192-9. ISSN 1573-076X. PMID 20842521. S2CID 28534016.

- Todres, Jonathan (December 2007). "Rights Relationships and the Experience of Children Orphaned by AIDS". UC Davis Law Review. 41.

- Children orphaned by AIDS : front-line responses from eastern and southern Africa. UNICEF. 1999. OCLC 59176094.

- Sinha, Aakanksha; Lombe, Margaret; Saltzman, Leia Y.; Whetten, Kathryn; Whetten, Rachel (March 2016). "Exploring Factors Associated with Educational Outcomes for Orphan and Abandoned Children in India". Global Social Welfare. 3 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1007/s40609-016-0043-7. ISSN 2196-8799. PMC 4830269. PMID 27088068.

- Beckerman, Karen Palmore (6 April 2002). "Mothers, orphans, and prevention of paediatric AIDS". The Lancet. 359 (9313): 1168–1169. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08248-X. PMID 11955530. S2CID 46158295.

- Ackerman Gulaid, Laurie. "National responses for children affected by AIDS: Review of progress and lessons learned" (PDF). Unicef.

- "AIDS Support Group". aidssupport.aarogya.com.

- "NGO for AIDS in India, HIV/AIDS Non Profit Campaign in India | End AIDS India". www.endaidsindia.org.

- "Solidarity and Action Against the HIV Infection in India". www.saathii.org.

- "Samapathik Trust, Pune - Home". Facebook.