Suicide in India

About 800,000 people die by suicide worldwide every year.[2] 164,033 Indians committed suicide in 2021 and the national suicide rate was 12 (calculated per hundred thousand or per lakh),[3] which is the highest rate of deaths from suicides since 1967, which is the earliest recorded year for this data.[4] According to The World Health Organization, in India, suicide is an emerging and serious public health issue.[5]

| Suicide |

|---|

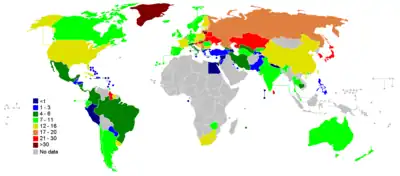

Suicide rates in India have been rising over the past five decades.[6] Suicides during 2021 increased by 7.2% in comparison to 2020 with India reporting highest number of suicides in the world.[3] India's contribution to global suicide deaths increased from 25.3% in 1990 to 36.6% in 2016 among women, and from 18.7% to 24.3% among men.[7] In 2016, suicide was the most common cause of death in both the age groups of 15–29 years and 15–39 years.[8] Between 1987 and 2007, the suicide rate increased from 7.9 to 10.3 per 100,000,[9] with higher suicide rates in southern and eastern states of India.[10] Daily wage earners registered 42,004 deaths by suicide in 2021, the biggest group in the suicide data.[11]

In 2021, Maharashtra recorded highest number of deaths by suicide(22,207) followed by Tamil Nadu(18,925), Madhya Pradesh(14,965) West Bengal(13,500), and Karnataka(13,056). These five states together accounted for almost half of the total suicides recorded in India in that year.[3]

The male-to-female suicide ratio in 2021 was 72.5 : 27.4.[12]

Estimates for number of suicides in India vary. For example, a study published in The Lancet projected 187,000 suicides in India in 2010,[13] while official data by the Government of India claims 134,600 suicides in the same year.[14] Similarly, for 2019, while NCRB reported India's suicide rate to be 10.4, according to WHO data, the estimated age-standardized suicide rate in India for the same year is 12.9. They have estimated it to be 11.1 for women and 14.7 for men.[15]

Definition

The Government of India classifies a death as suicide if it meets the following three criteria:[16]

- it is an unnatural death,

- the intent to die originated within the person,

- there is a reason for the person to end his or her life. The reason may have been specified in a suicide note or unspecified.

If one of these criteria is not met, the death may be classified as death because of illness, murder or in another statistical.

Statistics

| Contributing Factors | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Family problems | 32.4 |

| Illness | 17.1 |

| Drug abuse/alcohol addiction | 5.6 |

| Marriage related issues | 5.5 |

| Love affairs | 4.5 |

| Bankruptcy or indebtedness | 4.2 |

| Failure in examination | 2.0 |

| Unemployment | 2.0 |

| Professional/career problem | 1.2 |

| Property dispute | 1.1 |

| Death of dear person | 0.9 |

| Poverty | 0.8 |

| Suspected/illicit relation | 0.5 |

| Fall in social reputation | 0.4 |

| Impotency/infertility | 0.3 |

| Other causes | 11.1 |

| Causes not known | 10.3 |

Regional trends

Maharashtra reported the highest number of suicides at 18,916, followed by Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka. These five states collectively contributed to 49.5% of India's suicides in 2019. Nagaland reported only 41 suicides in the year. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka have consistently accounted for about 8.0% (or more) suicides in India across 2017 to 2019. Among the Union Territories, Delhi reported the highest number of suicides followed by Puducherry. Lakshadweep reported zero suicides. Bihar and Punjab reported a significant increase in the percentage of suicides in 2019 over 2018.[18]

Age and suicide in India

In 2019, the age groups 18–30 and 30–45 years accounted for 35.1% and 31.8% suicides in India, respectively. Combined, this age group of young adults accounted for 67% of total suicides. Thus, out of the total 1.39 lakh total suicides in India, 93,061 were young adults. This indicates that they are the most vulnerable age groups. Compared to 2018, youth suicide rates have risen by 4%.[19]

Literacy

In 2019, 12.6% victims of suicide were illiterate, 16.3% victims of suicide were educated up to primary level, 19.6% of the suicide victims were educated up to middle level and 23.3% of the suicide victims were educated up to matric level. Only 3.7% of total suicide victims were graduates and above.[16]

Suicide in cities

The number of deaths by suicide has seen an increasing trend from 2016 to 2019. In 2019, it increased by 4.6% compared to 2018. There were 25,891 suicides reported in the largest 53 mega cities of India in 2021. In the year 2021, Delhi City(2,760) recorded the highest number of deaths by suicide among the four metropolitan cities, followed by Chennai (2,699), Bengaluru (2,292) and Mumbai (1,436). These four cities together reported almost 35.5% of the total suicides reported from the 53 mega cities.[3]

Gender

In 2021, the male-to-female ratio of suicide victims was 72.5 : 27.4, while (70.9 : 29.1) in 2020. The total number of male suicides was 1,18,979 and female suicides accounted for 45,026.A total of 28 transgender people died by suicide. The proportion of female victims were more due to "marriage-related issues" (specifically in "dowry-related issues", and "impotency/infertility"). Of females who committed suicides, the highest number (23,178) was of house-wives followed by students (5,693) and daily wage earners (4,246).[12] Among males, maximum suicides were by daily wage earners (37,751), followed by self-employed persons (18,803) and unemployed persons (11,724).[20]

Dynamics

Domestic violence

Almost 40% of the world's total number of female suicides take place in India.[21] Domestic violence was found to be a major risk factor for suicide in a study performed in Bangalore.[22] In another study carried out in 2017, domestic violence was found to be a risk factor for attempted suicides among married women[23] This is found to be reflected in the NCRB 2019 data, where the proportion of female victims were more in "marriage-related issues" (specifically in "dowry-related issues").[24]

Suicide motivated by politics

Suicides motivated by ideology doubled between 2006 and 2008.[10] Mental health experts say these deaths illustrate the increasing stress on young people in a nation where, elections notwithstanding, the masses often feel powerless. Sudhir Kakar was quoted to say, "The willingness to die for a cause, as exemplified by Gandhi's epic fasts during the struggle for independence, is seen as noble and worthy. Ancient warriors in Tamil Nadu, in southeastern India, would commit suicide if their commander was killed."[25]

Mental illness

A large proportion of suicides occur in relation to psychiatric illnesses such as depression, substance use and psychosis.[26] The association between depression and death by suicide has been found to be higher among women. The National Mental Health Survey (NMHS) 2015–16 found that almost 80% of those suffering from mental illnesses did not receive treatment for more than a year.[27] The Indian government has been criticised by the media for its mental health care system, which is linked to the high suicide rate.[28][29]

Farmer's suicide in India

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported that in 2019, 10,281 people involved in the farming sector died by suicide. 5,957 were farmers/cultivators and 4,324 were agricultural labourers. Out of the 5,957 farmers/cultivators suicides, a total of 5,563 were male and 394 were female. Together, they accounted for 7.4% of total suicides in India in 2019.[30]

Student suicides in India

In 2021, according to NCRB data, 13,089 students died due to suicide, an increase from 12,526 student suicides in 2020. 43.49% of these were female, while 56.51% were male. Maharashtra reported the highest number of student suicides, registering 1,834 deaths, followed by Madhya Pradesh with 1,308, and Tamil Nadu with 1,246 deaths.[31]

At least one student commits suicide every hour in India. The year 2019 recorded the highest number of deaths by suicide (10,335) in the last 25 years. From 1995 to 2019, India lost more than 1.7 lakh students to suicide. Despite being one of the most advanced states in India, Maharashtra had the highest number of student suicides. In 2019, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh accounted for 44% of the total student suicides.[32]

Every hour one student commits suicide in India, with about 28 such suicides reported every day, according to data compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Maharashtra had the highest number of student suicides in 2018 with 1,448, followed by Tamil Nadu with 953 and Madhya Pradesh with 862. The NCRB data shows that 10,159 students committed suicide in 2018, an increase from 9,905 in 2017 and 9,478 in 2016.[33]

A Lancet study stated that suicide death rates in India are among the highest in the world and a large proportion of adult suicide deaths occur between the ages 15 and 29.[34]

Cram schools

Many suicides are attributed to the intense pressure and harsh regimen of students in cram schools (or coaching institutes). In the five years from 2011 to 2016, 57 students in Kota, dubbed the "coaching capital" of the country, died by suicide.[35] Cram schools or coaching institutes offer coaching to high school students for various college entrance exams, such as the JEE or NEET.[36][37]

Ragging

Ragging has been identified as a potential trigger for suicides.[38] Between 2012 and 2019, 54 ragging-related suicide incidents have occurred in the country.[39]

Suicide in the Indian Armed Forces

A total of 787 suicides have been reported in the Indian Armed Forces between 2014 and 2021. Of these, the Army reported 591 suicide cases, Navy reported 36, while the Indian Air Force reported 160 deaths by suicide.[40] More than half of the personnel in the Indian Army are under severe stress and many lives are being lost to suicides, fratricides and untoward incidents.[41]

Legislation

In India, suicide was illegal and the survivor would face jail term of up to one year and fine under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code. However, the government of India decided to repeal the law in 2014.[42] In April 2017, the Indian parliament decriminalised suicide by passing the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017[43][44] and the act commenced in July 2018.

Suicide prevention

Approaches to preventing suicide suggested in a 2003 monograph include:

- Reducing social isolation

- Preventing social disintegration

- Treating mental disorders[45]

- Regulating the sale of pesticides and ropes[45]

- Promoting psychological motivational sessions and meditation and yoga.[45]

State-led policies are being enforced to decrease the high suicide rate among farmers of Karnataka.[46]

See also

References

- Värnik, Peeter (2012). "Suicide in the World". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 9 (3): 760–771. doi:10.3390/ijerph9030760. PMC 3367275. PMID 22690161.

- Using the phrase 'commit suicide' is offensive to survivors and frightening to anyone contemplating taking his/her life. It's not the same as 'being committed' to a relationship or any other use of it as a verb. Suicide prevention (SUPRE) World Health Organization (2012)

- Narayanan, Jayashree (30 August 2022). "NCRB report 2021: 7.2 per cent increase in death by suicide; experts say 'busting myths, stigma is crucial'". The Indian Express. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Jha, Abhishek (29 August 2022). "Deaths by suicide at their highest rate in 2021, shows NCRB data". The Hindustan Times. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- "Suicide - India". who.int. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- Swain, Prafulla Kumar; Tripathy, Manas Ranjan; Priyadarshini, Subhadra; Acharya, Subhendu Kumar (29 July 2021). "Forecasting suicide rates in India: An empirical exposition". PLOS ONE. 16 (7): e0255342. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1655342S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255342. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8321128. PMID 34324554.

- Dandona, Rakhi; Kumar, G. Anil; Dhaliwal, R. S.; Naghavi, Mohsen; Vos, Theo; Shukla, D. K.; Vijayakumar, Lakshmi; Gururaj, G.; Thakur, J. S.; Ambekar, Atul; Sagar, Rajesh (1 October 2018). "Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016". The Lancet Public Health. 3 (10): e478–e489. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30138-5. ISSN 2468-2667. PMC 6178873. PMID 30219340.

- "Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016". Lancet. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Vijaykumar L. (2007), Suicide and its prevention: The urgent need in India, Indian J Psychiatry;49:81–84,

- Polgreen, Lydia (30 March 2010). "Suicides, Some for Separatist Cause, Jolt India". The New York Times.

- "'Daily wage earners' biggest group among death by suicides in 2021: NCRB". Business Standard. 30 August 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "45,026 females committed suicide in 2021, over half were housewives". The Hindu. 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Patel, V.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Vijayakumar, L.; Thakur, J. S.; Gajalakshmi, V.; Gururaj, G.; Suraweera, W.; Jha, P. (2012). "Suicide mortality in India: A nationally representative survey". The Lancet. 379 (9834): 2343–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60606-0. PMC 4247159. PMID 22726517.

- Suicides in India Archived 13 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Registrar General of India, Government of India (2012)

- "GHO | By category | Suicide rate estimates, age-standardized - Estimates by country". WHO. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- "Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India 2019" (PDF).

- "Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India - 2019 | National Crime Records Bureau".

- "Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India - 2019 | National Crime Records Bureau". ncrb.gov.in. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- "Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India - 2020 | National Crime Records Bureau". ncrb.gov.in. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- "Daily wage earners, self-employed, unemployed top categories dying by suicide in 2021". The Hindu. 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- "Nearly 40% of female suicides occur in India". The Guardian. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Gururaj, G; Isaac, M; Subhakrishna, DK; Ranjani, R (2004). "Risk factors for completed suicides: A case-control study from Bangalore, India". Inj Control Saf Promot. 11 (3): 183–91. doi:10.1080/156609704/233/289706. PMID 15764105. S2CID 29716380.

- Indu, Pankajakshan Vijayanthi; Remadevi, Sivaraman; Vidhukumar, Karunakaran; Shah Navas, Peer Mohammed; Anilkumar, Thekkethayyil Viswanathan; Subha, Nanoo (1 December 2020). "Domestic Violence as a Risk Factor for Attempted Suicide in Married Women". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 35 (23–24): 5753–5771. doi:10.1177/0886260517721896. ISSN 0886-2605. PMID 29294865. S2CID 20756262.

- "Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India - 2019 | National Crime Records Bureau". ncrb.gov.in. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Polgreen, Lydia (31 March 2010). "Suicides, Some for Separatist Cause, Jolt India". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Brådvik, Louise (September 2018). "Suicide Risk and Mental Disorders". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (9): 2028. doi:10.3390/ijerph15092028. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 6165520. PMID 30227658.

- "Understanding India's mental health crisis". Ideas For India. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "India's Mental Health Crisis". The New York Times. 30 December 2014.

- Bray, Carrick (4 November 2016). "Mental Daily Slams India's Mental Health System — Calls It 'Crippling', 'Misogynistic'". The Huffington Post.

- "Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India - 2019 | National Crime Records Bureau". ncrb.gov.in. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Verma, Tushar (1 September 2022). "Student suicides in India at a five-year high, most from Maharashtra". The Indian Express. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- Kumar, Chethan (7 September 2020). "One every hour: At 10,335, last year saw most student suicides in 25 years". The Times of India.

- Garai, Shuvabrata (29 January 2020). "Student suicides rising, 28 lives lost every day". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Patel, Vikram; Ramasundarahettige, Chinthanie; Vijayakumar, Lakshmi; Thakur, JS; Gajalakshmi, Vendhan; Gururaj, Gopalkrishna; Suraweera, Wilson; Jha, Prabhat; Million Death Study Collaborators (2012). "Suicide mortality in India: a nationally representative survey". The Lancet. 379 (9834): 2343–2351. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60606-0. PMC 4247159. PMID 22726517.

{{cite journal}}:|author9=has generic name (help) - "Why 57 Young Students Have Taken Their Lives In Kota". HuffPost India. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "After 50 student suicides, Andhra and Telangana govts wake up to looming crisis". The News Minute. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Iqbal, Mohammed (29 December 2018). "The dark side of Kota's dream chasers". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Deepika, K. c (6 August 2015). "Ragging leads to 15 suicides in 18 months". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "To stop ragging-related suicides, Modi govt to make 1-week induction mandatory in colleges". The Print. 26 July 2019.

- "787 suicides reported in armed forces since 2014, most from Army, govt data shows". The Print.

- Peri, Dinakar (8 January 2021). "Over half of Army personnel under severe stress: study". The Hindu.

- "Govt decides to repeal Section 309 from IPC; attempt to suicide no longer a crime". Zee News. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Mental health bill decriminalising suicide passed by Parliament". The Indian Express. 27 March 2017. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- THE MENTAL HEALTHCARE ACT, 2017 (PDF). New Delhi: The Gazette of India. 7 April 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2017.

- Singh A.R., Singh S.A. (2003), Towards a suicide free society: identify suicide prevention as public health policy, Mens Sana Monographs, II:2, p3-16. [cited 2011 Mar 7]

- Deshpande, R S (2002), Suicide by Farmers in Karnataka: Agrarian Distress and Possible Alleviatory Steps, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 37 No 25, pp2601-10