Suicide in Ireland

Suicide in Ireland has the 17th highest rate in Europe and the 4th highest for the males aged 15–24 years old which was a main contributing factor to the improvement of suicides in Ireland (World Health Organization, 2012).

| Suicide |

|---|

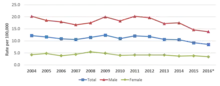

On average, adjusted for age, The Central Statistics Office provided the overall suicide rate has a decreasing trend, which is from 13.5 per 100,000 population in 2001 to 8.5 in 2016 (The National Suicide Research Foundation, 2016).

The suicide rate was significantly higher in males than females (OECD, 2018). Also, Irish young men and women suicide rate also had recorded the highest rate in Europe (Richardson et al., 2013; European Child Safety Alliance, 2014).

Hanging is the most common suicide method that people in Ireland used (Departments of Public Health, 2001). The second common method is drowning (Departments of Public Health, 2001). Then, shooting, and overdose respectively (Departments of Public Health, 2001).

The WHO stated that strong partnership such as media, school, and the government should be working together and giving support to prevent suicide (WHO, 2014).

Statistics

The National Suicide Research Foundation (NSRF) has kept a record on the Irish suicide rate.

| Year | Male | Female | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 16.7 | 4.4 | 10.6 | |||||||

| 2008 | 17.5 | 5.4 | 11.4 | |||||||

| 2009 | 20 | 4.9 | 12.4 | |||||||

| 2010 | 17.9 | 3.9 | 11.1 | |||||||

| 2011 | 20.2 | 4.2 | 12.1 | |||||||

| 2012 | 19.6 | 4.1 | 11.8 | |||||||

| 2013 | 17.2 | 4.1 | 10.6 | |||||||

| 2014 | 17.5 | 3.7 | 10.5 | |||||||

| 2015 | 14.6 | 3.8 | 9.2 | |||||||

| 2016 | 13.8 | 3.4 | 8.5 | |||||||

| Source: Central Statistics Office (Ireland), The National Suicide Research Foundation | ||||||||||

Overall, Ireland has the trend of decreasing suicide rate in recent years. From 2011, the population has decreased from 12.1 per 100,000 population to 8.5 per 100,000 population in 2016 (NSRF, 2016). Youth suicide as a main contributing factor to the Irish suicide rate increased. A report (Richardson et al., 2013) stated that Irish young males had the highest number of suicides in Europe from the EU context, while another report showed Irish young females also experienced the highest suicide rate in Europe in 2018 (European Child Safety Alliance, 2014).

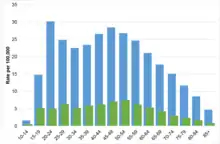

The National Suicide Research Foundation (2016) indicated the highest rate of suicide in Ireland for male was 30 per 100,000 population, aged 20–24, while that of female was approximately 7 per 100,000 population aged 50–54 between 2007 and 2015. Male suicide rate was significantly higher than female, especially in 2011, where it was around 5 times higher in male than female (NSRF, 2016). A report in 2018 indicated that in 400 suicides, 8 of 10 are men (Ryan, 2018).

Common methods

A national study in Ireland in 2001, showed the most common method that people used to suicide in Ireland is hanging (Departments of Public Health, 2001; Biddle et al., 2010). Other suicide methods commonly used in Ireland included drowning, shooting, and overdose respectively (Departments of Public Health, 2001).

Gender

For gender, males were more likely to kill themselves in a more violent way such as hanging or shooting, while females were more apparent to drown, overdose or poison themselves in order to suicide (Departments of Public Health, 2001).

Age

For ages, younger people aged 15–24 were more likely to use hanging to suicide, while adults aged 25–34 years old were found more common in drug overdose and self-poisoning (Arensman et al., 2016). Therefore, the population of suiciding by hanging would reduce when people got older, and yet increased in firearms suicide (Arensman et al., 2016).

Risk factors

Unemployment

Unemployment was strongly associated with Ireland's suicide rate. According to the studies, the unemployment rate in Ireland had a decreasing trend from January 2012 of 16% to January 2016 which is 9% (Eurostat, 2019). At this period, the Ireland suicide rate was also decreasing from 2012 (11.8 per 100,000 population) to 2016 (8.5 per 100,000 population) (NSRF, 2016). The result showed a higher unemployment rate contributed to a higher suicide rate in Ireland. People who were unemployed usually experienced health problems that made them unable to work, thereby increased their stress of life and financial difficulties, leading to deceleration of self-esteem (Preti & Miotto, 1999). Moreover, high levels of stress and financial difficulties might pose negative impacts on their mental health, which caused attempt to die by suicide and self-harm (MFHA, 2016). However, limitations do exist. It was difficult to understand whether unemployment contributed to the promotion of dying by suicide (Departments of Public Health, 2001). Between 2002-2008, the unemployment rate is significantly lower than in other years, but the suicide rate was not influenced by the unemployment rate (Eurostat, 2019; NSRF, 2016). Therefore, other risk factors should also be considered in promoting suicide intentions in Ireland.

Mental illness

Mental illness is another main contributing factor that increased the risk of suicide. A report showed that Ireland was one of the countries of highest rates of mental illness in Europe, and the problem of mental illness cost over €8.2 billion a year in Ireland (Cullen, 2018). 18.5% of the population in Ireland reported that they were suffering from mental illness in 2016, and the rate of depression in both males and females were above the European average (Cullen, 2018). 28% of Irish children aged between 11 and 15 years had reported that they had experienced bullying in school, in which 14% were cyberbullying. This might contribute to mental illness and promote suicide intentions (Cullen, 2018). Moreover, females were more likely to experience mental illness and attend mental health services than males (Gavigan & McKeon, 2007). This could be explained by slower recognition of depression and lower intention to seek help for males (Gavigan & McKeon, 2007). As a result, this might be another significant factor why males have contributed to higher suicide rate than females. In addition, a large number of people who experienced mental illness would take drug or medicine such as antidepressant to reduce the pressure that might also lead to increase the risk of suicide (Departments of Public Health, 2001).[1]

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption also is significantly linked with the morality of suicide. The studies showed more than half of the people who committed suicide were also related to alcohol, also more than one-third of those who drank alcohol had hurt themselves (GRIFFIN, 2014). The World Health Organization stated that people who experienced alcohol abuse were 8 times more likely to do things unconsciously than people who didn't (WHO, 2004). Also, males seemed to drink more than female especially the younger ones (Departments of Public Health, 2001). Therefore, leading the young males aged 15–24 turned up the greatest suicide rate compared to the rest of the age groups (NSRF, 2016). Evidence showed that there was a high amount of alcohol consumption by young people usually in the weekend and public holiday as they might drink when hanging with friends or having a party (Arensman et al., 2016). Young people who drank at an earlier age might also make them drink regularly and more in the future (Departments of Public Health, 2001). Heavy drinking or alcohol abuse had a negative influence on people's mental health, especially for the young people, which increased their feeling of depression and anxiety leading to increase self-harm and suicide (Departments of Public Health, 2001).

Suicide prevention

Suicidal thought is often a temporal thought of mind which is possible to help and provide emotional support to those people who had strong depression and anxiety, in order to reduce the risk of suicide (Health Service Executive, 2011). A focused campaign indicated that the suicide rates among 25–34 years old men decreased (Health Service Executive, 2011). According to the Irish Probable Suicide Deaths Study (IPSDS), men are three times more likely to die from suicide than women and age range in between 35-54 is at most risk of taking their own lives.[2]

The WHO stated that strong partnership works together as a core element to prevent suicide (WHO, 2014). Media, school, and the government are the three major sectors which play a significant role in suicide prevention and giving support.

Media

The media, including the news, television, film and the internet, play a significant role in suicide prevention, especially for the younger people (Biddle et al., 2012). A study shows that teenagers are more easily affected by social media (Lin et al., 2010). The media might spread out the information to the public about the impact and the lethality rate of suicide, as well the characteristics of the suicide method especially hanging (Arensman et al., 2016). Media also takes part in promoting suicide prevention awareness, reporting suicide and providing information for assistance if someone who is thinking about committing suicide (Arensman et al., 2016).

Hanging is the most common suicide method that the Irish used, especially for young people (Departments of Public Health, 2001). The suicide method that people choose is significantly related to how they perceived the information of suicide cases (Cantor & Baume, 1998). Thus, media is an important sector that linked to reducing people's cognitive availability of hanging. For example, the media should report fewer details of the suicide cases that involve hanging, such as pictures and videos (Arensman et al., 2016). The media should also follow the media guideline that avoids using profanity and sensationalism (Samaritans, 2013).

School

The studies showed that the suicide rate was higher in young people. Hence, the school should infuse positive mental health to their students for suicide prevention among this age group. There are different programs that can be supported by the school. For example, MindOut training is a program which was developed in 2004 by the Health Promotion Research Centre in NUI Galway and the HSE's Health Promotion and Improvement Department (HSE, 2018). This program is based on the feedback from the teacher and the young people, and elaborated by the researchers. It has been proven to improve young people's overall mental health and wellbeing, strengthen their emotional competence, and the ability to cope with their own personal difficulties (HSE, 2018). Teachers and parents are the most important stakeholders for the school to promote these approaches (HSE, 2018).

In addition, the school should educate their students on how drinking alcohol and taking drug might impact their mental health and increase the feeling of depression (Arensman et al., 2016). Moreover, they should as well explain how drugs and alcohol contribute to suicide intentions (Arensman et al., 2016).

Government

The Government of Ireland proposed to decrease the mortality rate of suicide and improve national overall mental health and wellbeing by several approaches. These include providing society better suicide awareness, giving support to the communities, improving safety, access and quality of the service, better research and use target approaches to identify the specified priority group of suicide, etc. (HSE, 2017). The government also aimed to reduce the overall suicide rate and self-harm rate of the whole population by the project "Connecting of life" (Department of Health, 2015).

Connecting for life, which is the national office's project, aimed to reduce the suicide rate in 2015-2020 (Department of Health, 2015). This project provides free and evidence-based suicide and self-harm training which aimed to increase public awareness and governmental support for suicide prevention. In 2017, over 12000 Irish people have completed programs such as Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) (Department of Health, 2015). Currently, all 17 local action plans are placed for supporting suicide prevention (Department of Health, 2015). The National Office had funded more than €11.9 million in 2017, and approximately 60% of the fund was used in agencies and front-line services for meeting the target of Connecting for life and researching (Department of Health, 2015).

Notes

- Arensman, Ella & Bennardi, Marco & Larkin, Celine & Wall, Amanda & Mcauliffe, Carmel & McCarthy, Jacklyn & Williamson, Eileen & J. Perry, Ivan. (2016). Suicide among Young People and Adults in Ireland: Method Characteristics, Toxicological Analysis, and Substance Abuse Histories Compared. PLOS ONE. 11. e0166881. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166881.

- Biddle, L., Gunnell, D., Owen-Smith, A., Potokar, J., Longson, D., Hawton, K., ... Donovan, J. (2012). Information sources used by the suicidal to inform choice of method. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 702–709.

- Burke, S., & McKeon, P. (2007). Suicide and the reluctance of young men to use mental health services. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 24(2), 67–70. doi:10.1017/S0790966700010260

- Central Statistics Office. (2013). Vital Statistics Fourth Quarter and Yearly Summary

- Child Safety Europe. (2014). What are European countries doing to prevent intentional injury to children?

- Cullen, P. (2018). Ireland has one of the highest rates of mental health illness in Europe, report finds. THE IRISH TIMES

- Department of Health. (2015). Connecting for life : Ireland's national strategy to reduce suicide 2015-2020. Ireland, Dublin : Department of Health

- Departments of Public Health. (2001). Suicide in Ireland. Departments of Public Health.

- eurostat. (2019). Unemployment by sex and age - monthly average.

- GRIFFIN, E., ARENSMAN, E., PAUL CORCORAN, P., CHRISTINA B DILLON, C., WILLIAMSON, E., PERRY, I. (2014). NATIONAL SELF-HARM REGISTRY IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2014, The National Suicide Research Foundation.

- Lin, Jin-Jia & Chang, Shu-Sen & Lu, Tsung-Hsueh. (2010). The leading methods of suicide in Taiwan, 2002-2008. BMC public health. 10. 480. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-480.

- Mental Health First Aid (2016) HELPING SOMEONE WITH MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS AND FINANCIAL DIFFICULTIES: GUIDELINES FOR THE SUPPORT PERSON

- OECD/European Union. (2018). “Promoting mental health in Europe: Why and how?”, in Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union, Brussels. doi:10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-4-en

- Ryan, O. (2018). Men account for eight in 10 suicides in Ireland. TheJournal.ie

- Preti, A., & Miotto, P. (1999). Suicide and unemployment in Italy, 1982-1994. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 53(11), 694–701. doi:10.1136/jech.53.11.694

- Richardson, N., Clarke, N., & Fowler, C. (2013). A report on the all-Ireland young men and suicide project. Carlow: Men's Health Forum in Ireland.

- Samaritans. (2013) MEDIA GUIDELINES for Reporting Suicide. Samaritans.

- The Health Service Executive. (2011). Suicide. The Health Service Executive.

- The Health Service Executive. (2017). National Office for Suicide Prevention Annual Report 2017. The Health Service Executive.

- The Health Service Executive. (2018). Launch of newly revised MindOut Programmes for schools. The Health Service Executive.

- The National Suicide Research Foundation. (2016). Suicide. The National Suicide Research Foundation.

- World Health Organization. (2012). Programmes and Projects, Mental Health, Suicide Prevention, Country Reports and Charts. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2004). Global Status Report on Alcohol. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: a global imperative. World Health Organization.

References

- "'A lot of young people with ADHD feel misunderstood by family and in school'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2022-11-25.

- Baker, Noel (2022-11-25). "Number of deaths by suicide in Ireland may be far higher than official statistics record". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 2022-11-25.