HMS Cressy (1899)

HMS Cressy was a Cressy-class armoured cruiser built for the Royal Navy around 1900. Upon completion she was assigned to the China Station. In 1907 she was transferred to the North America and West Indies Station before being placed in reserve in 1909. Recommissioned at the start of World War I, she played a minor role in the Battle of Heligoland Bight a few weeks after the beginning of the war. Cressy and two of her sister ships were torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-9 on 22 September 1914 with the loss of 560 of her crew.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Cressy |

| Namesake | Battle of Crécy |

| Builder | Fairfield Shipbuilding, Govan |

| Laid down | 12 October 1898 |

| Launched | 4 December 1899 |

| Completed | 28 May 1901 |

| Fate | Sunk by SM U-9, 22 September 1914 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Cressy-class armoured cruiser |

| Displacement | 12,000 long tons (12,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 472 ft (143.9 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 69 ft 6 in (21.2 m) |

| Draught | 26 ft 9 in (8.2 m) (maximum) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Complement | 725–760 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

Design and description

Cressy was designed to displace 12,000 long tons (12,190 t). The ship had an overall length of 472 feet (143.9 m), a beam of 69 feet 9 inches (21.3 m) and a deep draught of 26 feet 9 inches (8.2 m).[1] She was powered by two 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one shaft, which produced a total of 21,000 indicated horsepower (15,660 kW) and gave a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The engines were powered by 30 Belleville boilers. On her sea trials, Cressy only reached 20.7 knots (38.3 km/h; 23.8 mph), the slowest performance of any of her class.[2] She carried a maximum of 1,600 long tons (1,600 t) of coal and her complement ranged from 725[3] to 760 officers and ratings.[4]

Her main armament consisted of two breech-loading (BL) 9.2-inch (234 mm) Mk X guns in single gun turrets, one each fore and aft of the superstructure.[3] They fired 380-pound (170 kg) shells to a range of 15,500 yards (14,200 m).[5] Her secondary armament of twelve BL 6-inch Mk VII guns was arranged in casemates amidships. Eight of these were mounted on the main deck and were only usable in calm weather.[6] They had a maximum range of approximately 12,200 yards (11,200 m) with their 100-pound (45 kg) shells.[7] A dozen quick-firing (QF) 12-pounder 12-cwt guns were fitted for defence against torpedo boats, eight on casemates on the upper deck and four in the superstructure.[8] The ship also carried three 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and two submerged torpedo tubes.[4]

The ship's waterline armour belt had a maximum thickness of 6 inches (152 mm) and was closed off by 5-inch (127 mm) transverse bulkheads. The armour of the gun turrets and their barbettes was 6 inches thick while the casemate armour was 5 inches thick. The protective deck armour ranged in thickness from 1–3 inches (25–76 mm) and the conning tower was protected by 12 inches (305 mm) of armour.[4]

Service history

Cressy, named after the 1346 Battle of Crécy,[9] was laid down by Fairfield Shipbuilding at their shipyard in Govan, Scotland on 12 October 1898 and launched on 4 December 1899.[4] After finishing her sea trials she passed into the fleet reserve at Portsmouth on 24 May 1901.[10] She was commissioned for service on the China Station on 28 May 1901,[11] but her departure was delayed for several months when her steering gear broke down shortly after leaving the base and she had to return. She eventually left home waters in early October 1901, arriving at Colombo on 7 November,[12] and then Singapore on 16 November.[13] She was assigned to the North America and West Indies Station from 1907 through 1909 and placed in reserve upon her return home.[9]

The ship was assigned to the 7th Cruiser Squadron shortly after the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. The squadron was tasked with patrolling the Broad Fourteens of the North Sea in support of a force of destroyers and submarines based at Harwich which protected the eastern end of the English Channel from German warships attempting to attack the supply route between England and France. During the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August, the ship was part of Cruiser Force 'C', in reserve off the Dutch coast, and saw no action.[14] After the battle, Rear Admiral Arthur Christian ordered Cressy to take aboard 165 unwounded German survivors from the badly damaged ships of Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt's Harwich Force. Escorted by her sister Bacchante, she set sail for the Nore to unload their prisoners.[15]

Fate

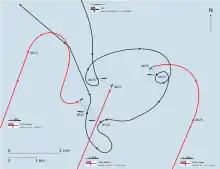

On the morning of 22 September, Cressy and her sisters, Aboukir and Hogue, were on patrol without any escorting destroyers as these had been forced to seek shelter from bad weather. The three sisters were steaming in line abreast about 2,000 yards (1,800 m) apart at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). They were not expecting submarine attack, but had lookouts posted and one gun manned on each side to attack any submarines sighted. The weather had moderated earlier that morning and Tyrwhitt was en route to reinforce the cruisers with eight destroyers.[16]

U-9, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen, had been ordered to attack British transports at Ostend, but had been forced to dive and take shelter from the storm. On surfacing, she spotted the British ships and moved to attack. She fired one torpedo at 06:20 at Aboukir which struck her on the starboard side; the ship's captain thought he had struck a mine and ordered the other two ships to close to transfer his wounded men. Aboukir quickly began listing and capsized around 06:55 despite counterflooding compartments on the opposite side to right her.[17]

As Hogue approached her sinking sister, her captain, Wilmot Nicholson, realized that it had been a submarine attack and signaled Cressy to look for a periscope although his ship continued to close on Aboukir as her crew threw overboard anything that would float to aid the survivors in the water. Having stopped and lowered all her boats, Hogue was struck by two torpedoes around 06:55. The sudden weight loss of the two torpedoes caused U-9 to broach the surface and Hogue's gunners opened fire without effect before the submarine could submerge again. The cruiser capsized about ten minutes after being torpedoed and sank at 07:15.[18]

Cressy attempted to ram the submarine, but did not succeed and resumed her rescue efforts until she too was torpedoed at 07:20. Weddigen had fired two torpedoes from his stern tubes, but only one hit. U-9 had to maneuver to bring her bow around with her last torpedo and fired it at a range of about 550 yards (500 m) at 07:30. The torpedo struck on the port side and ruptured several boilers, scalding the men in the compartment. As her sisters had done, Cressy took on a heavy list and then capsized before sinking at 07:55. Several Dutch ships began rescuing survivors at 08:30 and were joined by British fishing trawlers before Tyrwhitt and his ships arrived at 10:45. From all three ships 837 men were rescued and 62 officers and 1,397 ratings lost:[19] 560 of those lost were from Cressy.[9]

In 1954 the British government sold the salvage rights to all three ships to a German company and they were subsequently sold again to a Dutch company which began salvaging the wrecks' metal in 2011.[20][21]

Notes

Footnotes

- Friedman 2012, pp. 335–36

- Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 69

- Friedman 2012, p. 336

- Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 68

- Friedman 2011, pp. 71–72

- Friedman 2012, pp. 243, 260–61

- Friedman 2011, pp. 80–81

- Friedman 2012, pp. 243, 336

- Silverstone, p. 224

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36456. London. 16 May 1901. p. 6.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36467. London. 28 May 1901. p. 4.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36608. London. 9 November 1901. p. 8.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36616. London. 19 November 1901. p. 10.

- Corbett, pp. 100, 171–72

- Osborne, p. 103

- Corbett, pp. 172–75

- Massie, p. 133

- Massie, pp. 133–35

- Massie, p. 135

- "Booty Trawl". Private Eye. Pressdram (1302): 31. 2011.(subscription required)

- Ambrogi, Stefano (12 October 2011). "Scrap metal hunt is wrecking UK warship graves - veterans". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

Bibliography

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Corbett, Julian (March 1997). Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd, reprint of the 1938 ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-256-X.

- Firme, Tim; Johnson, Harold & MacDonald, Kevin C. (2005). "Question 27/04: British WW I Armored Cruiser Wrecks". Warship International. XLII (3): 242. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2012). British Cruisers of the Victorian Era. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-59114-068-9.

- Massie, Robert K. (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04092-8.

- Osborne, Eric W. (2006). The Battle of Heligoland Bight. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34742-4.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.