HMT Empire Windrush

HMT Empire Windrush, originally MV Monte Rosa, was a passenger liner and cruise ship launched in Germany in 1930. She was owned and operated by the German shipping line Hamburg Süd in the 1930s under the name Monte Rosa. During World War II she was operated by the German navy as a troopship. At the end of the war, she was taken by the British Government as a prize of war and renamed the Empire Windrush. In British service, she continued to be used as a troopship until March 1954, when the vessel caught fire and sank in the Mediterranean Sea with the loss of four crewmen. HMT stands for "His Majesty's Transport" and MV for "Motor Vessel".

Empire Windrush | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | MV Monte Rosa (1930–1947) |

| Namesake | Monte Rosa |

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | Hamburg (1930–40) |

| Builder | Blohm & Voss, Hamburg |

| Yard number | 492 |

| Launched | 13 December 1930 |

| Maiden voyage | 28 March 1931–30 June 1931, Hamburg – South America – Hamburg |

| Out of service | May 1945 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Seized by the United Kingdom as a war reparation |

| Name | HMT Empire Windrush |

| Namesake | River Windrush |

| Owner |

|

| Operator | New Zealand Shipping Company |

| Port of registry | London |

| Acquired | November 1945 |

| In service | 1947 |

| Out of service | 30 March 1954 |

| Fate | Sank after catching fire |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage |

|

| Length | 500 ft 3 in (152.48 m) |

| Beam | 65 ft 7 in (19.99 m) |

| Depth | 37 ft 8 in (11.48 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 SCSA diesel engines (Blohm & Voss, Hamburg), double reduction geared driving two propellers. |

| Speed | 14.5 knots (26.9 km/h) |

| Part of a series on the |

| British African-Caribbean community |

|---|

| Community and subgroups |

| History |

| Languages |

| Culture |

| People |

In 1948, Empire Windrush brought a large group of West Indian immigrants to the United Kingdom, carrying 1,027 passengers and two stowaways on a voyage from Jamaica to London.[1][2] 802 of these passengers gave their last country of residence as somewhere in the Caribbean: of these, 693 intended to settle in the United Kingdom.[1] Additionally, the ship carried 66 Polish people intending to settle in Britain.[3]

Windrush was not the first ship to carry a large group of West Indian people to the United Kingdom, as two other ships had arrived the previous year.[4] But Windrush's 1948 voyage became very well-known; British Caribbean people who came to the United Kingdom in the period after World War II, including those who came on other ships, are sometimes referred to as the Windrush generation.

Background and description

Empire Windrush, under the name Monte Rosa, was the last of five almost identical Monte-class passenger ships that were built between 1924 and 1931 by Blohm & Voss in Hamburg for Hamburg Süd (Hamburg South American Steam Shipping Company).[5]

During the 1920s, Hamburg Süd believed there would be a lucrative business in carrying German emigrants to South America (see German Argentine). The first two ships (MV Monte Sarmiento and MV Monte Olivia) were built for that purpose with single-class passenger accommodation of 1,150 in cabins and 1,350 in dormitories. In the event, the emigrant trade was less than expected and the two ships were repurposed as cruise ships, operating in Northern European waters, the Mediterranean and around South America.[5]

This proved to be a great success. Until then, cruise holidays had been the preserve of the rich. But by providing modestly priced cruises, Hamburg Süd was able to profitably cater to a large new clientele.[5] Another ship was commissioned to cater for the demand – the MV Monte Cervantes, which struck an uncharted rock and sank after only two years in service. Despite this, Hamburg Süd remained confident in the design and quickly ordered two more ships, the MV Monte Pascoal and the MV Monte Rosa.[5]

Monte Rosa was 500 ft 6 in (152.55 m) long, with a beam of 65 ft 8 in (20.02 m). She had a depth of 37 ft 9 in (11.51 m). The ship was assessed at 13,882 GRT, 7,788 NRT.[6]

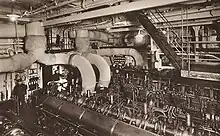

Engines and machinery

The five Monte-class vessels were diesel-powered motor ships. At the time, the use of diesel engines was highly unusual in ships of this size, which would have been typically steam-powered. The first two to be launched, Monte Sarmiento and Monte Olivia, were in fact the first large diesel-powered passenger ships to see service with a German operator.[7] The use of diesel engines reflected the experience Blohm & Voss had gained by building diesel-powered U-boats during World War I.[5]

Windrush carried four oil-burning four-stroke single-acting MAN diesel engines with a combined output of 6,880 horsepower (5,130 kW). They were single-reduction geared in pairs to two propellers. The ships' top speed was 14 knots (26 km/h) (around half the speed of the large trans-Atlantic Ocean liners of the era), but this was considered adequate for both the immigrant and cruise business.[5]

Electrical power was initially provided by three 350-kW DC electric generators, powered by internal combustion engines and installed in the engine room; a fourth generator was added in 1949. There was also an emergency generator outside the engine room. The ship also carried two Scotch marine boilers to produce high-pressure steam for some auxiliary machinery. These could be heated either by burning diesel fuel or by using the hot exhaust gases from the main engines.[8]

Naming

The Monte-Class ships were named after mountains in Europe or South America. Monte Rosa was named after Monte Rosa, a mountain massif located on the Swiss-Italian border and the second-highest mountain in the Alps.

The ship was renamed in British service. Merchant ships in service with the United Kingdom Government during and after World War 2 had names prefixed with the word Empire. These vessels were known as Empire ships and numbered around 1,300. Windrush was one of around sixty empire ships that were named after British rivers.[Note 1] Empire Windrush's namesake, the River Windrush is a small tributary of the Thames, that flows through the Cotswolds towards Oxford.

The ship's designation prefix was also changed, from "MV" (Motor Vessel) to "HMT". This was used for British troopships and could stand for "His Majesty's Troopship", "His Majesty's Transport"[9][10] or "Hired Military Transport".[11][Note 2] Some official documents, such as the enquiry report into the ship's loss, used "MV Empire Windrush" instead of "HMT".[8]

Official Numbers are ship identifier numbers assigned to merchant ships by their country of registration. Each country developed its own official numbering system, some on a national and some on a port-by-port basis, and the formats have sometimes changed over time. National Official Numbers are different from IMO Numbers. Flag states still use national systems, which also cover those vessels not subject to the IMO regulations. Monte Rosa had the German Official Number 1640. She used the Maritime call sign RHWF until 1933[12] and then DIDU until 1945.[13] When the ship sank in 1954 she had the British Official Number 181561.[8]

Early history

Monte Rosa was launched on 13 December 1930[14] and was delivered in early 1931 to Hamburg Süd. After sea trials, she departed from Hamburg on her first voyage to South America on 28 March, arriving back on 22 June.[14]

Monte Rosa's entry into service came just as the Great Depression was causing a serious downturn in Hamburg Süd's cruise business. It was not until 1933 that this picked up again, when the older ships, Monte Sarmiento and Monte Olivia reverted to their original role of carrying migrants to South America while Monte Pascoal and Monte Rosa were used for cruises, to Norway and the United Kingdom;[5] Monte Rosa also continued to carry immigrants to South America, making more than 20 return-trips before the outbreak of World War II.[14]

After the Nazi regime came to power in Germany in 1933, the ship was used by the party to help spread its ideology. In 1937, she and Monte Olivia, and Monte Sarmiento were chartered to provided cruise holidays for the state-owned Kraft durch Freude ('Strength through Joy') programme.[15] This provided concerts, lectures, sports activities and cheap holidays as a means of strengthening support for the Nazi regime and indoctrinating people in its ideology.[16]

When visiting South America, the ship was used to spread Nazi ideology among the German-speaking community there. When in port in Argentina, she hosted Nazi rallies for German-Argentine people. In 1933, the new German ambassador, Baron Edmond von Thermann, arrived in Argentina on the Monte Rosa. He disembarked in front of an enthusiastic crowd wearing an SS uniform; he would spend his time in office actively proselytising Nazi ideology.[14] The ship was also used as a venue for Nazi gatherings when docked in London.[17]

Monte Rosa ran aground off Thorshavn, Faroe Islands, on 23 July 1934,[18] but was refloated the next day.[19] In 1936, the ship made a rendezvous at sea with the airship LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin. During the manoeuvre, a bottle of champagne was hoisted from the Monte Rosa to the airship.[20]

German World War II service

At the start of World War II, Monte Rosa was allocated for military use. She was used as a barracks ship at Stettin, then as a troopship for the invasion of Norway in April 1940. She was later used as an accommodation and recreational ship attached to the battleship Tirpitz, stationed in the north of Norway, from where Tirpitz and her flotilla attacked the Allied convoys en route to Russia.

In November 1942, she was one of several ships used for the deportation of Norwegian Jewish people.[21] The ship made two trips from Oslo to Denmark on the 19th and the 26th of November,[22] carrying a total of 46 people. They included the Polish-Norwegian businessman and humanitarian Moritz Rabinowitz. Of the 46, all but two were murdered at Auschwitz concentration camp.[23][24] In September 1943, the ship was to be used for the deportation of Danish Jewish people. The German chief of sea transport at Aarhus in Denmark, together with Monte Rosa's captain, Heinrich Bertram (captain), conspired to prevent this by falsely reporting serious engine trouble to the German High Command. This action may have contributed to the Rescue of the Danish Jews.[25]

In September 1943, the Tirpitz was badly damaged by British X-class submarines at Altafjord in Norway, during Operation Source. The Germans were unwilling to risk moving the ship to a German dockyard for repair, so in October Monte Rosa was used to carry hundreds of civilian workers and engineers to Altafjord where they would repair the Tirpitz in situ.[26] During this time, Monte Rosa was docked alongside the battleship to act as accommodation for the workers.[27]

Air attack

During the winter of 1943–1944, Monte Rosa continued to shuttle between Norway and Germany.[26] On 30 March 1944, she was attacked by British and Canadian Bristol Beaufighters. The strike was mounted for the explicit purpose of sinking her after a reconnaissance aircraft from 333 (Norwegian) Squadron had obtained details of the ship's movements.[28][29] The ship was travelling south, escorted by two flak ships, a destroyer and by German fighters.[28] The attacking force consisted of nine aircraft from Royal Air Force (RAF) 144 Squadron, five of which carried torpedoes; and nine aircraft from Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) 404 Squadron, all armed with armour-piercing RP-3 rockets.[29]

The attack took place close to the Norwegian island of Utsira.[29] The RCAF and RAF crews claimed two torpedo hits on Monte Rosa; the ship was also struck by eight rockets and by cannon fire.[30][28] One German Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighter was shot down and two 404 Squadron Beaufighters were lost. The two crew of one aircraft were killed; the crew of the other (one of whom was the squadron commanding officer) survived to become prisoners of war.[29][28][31] Despite her damage, Monte Rosa was able to reach Aarhus in Denmark on 3 April.[28]

Sabotage attack

In June 1944, Max Manus and Gregers Gram, members of Norwegian Independent Company 1 (a British Army sabotage and resistance unit composed of Norwegians), attached limpet mines to Monte Rosa's hull while the ship was in Oslo harbour. They had learned the ship was to carry 3,000 German troops back to Germany and their purpose was to sink her during the trip.[32] The pair had twice bluffed their way into the dock area by posing as electricians, then hid for three days as they waited for the ship to arrive. After it docked, they paddled out to her from their hiding place on an inflatable rubber boat and attached their mines.[33] The mines detonated when the ship was near Øresund, damaging the hull; she remained afloat and returned to harbour under her own power.[34]

Later wartime service

In September 1944, the vessel was damaged by another explosion, possibly from a mine. Odd Claus, a Norwegian boy with German parents who was being forcibly taken to Germany, was one of those on board when this happened. In his 2008 memoirs, he wrote that as well as German troops, the vessel was carrying Norwegian women with young children, who were being taken to Germany as part of the Lebensborn programme. He notes the explosion happened at 5 am, and states that around 200 on board were trapped and drowned as the ship's captain closed the watertight bulkhead doors to control flooding and stop the ship from sinking.[35]

On 16 February 1945, Monte Rosa was damaged by a mine explosion near the Hel Peninsula in the Baltic, With a flooded engine room, the ship was towed to the German-occupied Polish port of Gdynia for temporary repairs. The ship was then towed to Copenhagen, carrying 5,000 German refugees who were fleeing from the advancing Red Army. She was taken to Kiel and on 10th May 1945 was captured there by British forces.[36][37]

Postwar British service

Over the summer of 1945, Monte Rosa's wartime damage was repaired in a Danish dockyard. On the 18 November 1945, ownership was transferred to the United Kingdom as a prize of war.[37]

In 1947, Monte Rosa was assigned to the British Ministry of Transport and registered as a British vessel.[8]

By this time, she was the only survivor of the five Monte-class ships. Monte Cervantes sank near Tierra del Fuego in 1930. Two ships were sunk in Kiel harbour by separate wartime air-raids, Monte Sarmiento in February 1942 and Monte Olivia in April 1945.[38] Monte Pascoal was damaged by an air-raid on Wilhelmshaven in February 1944; in 1946 she was filled with chemical bombs and scuttled by the British in the Skagerrak.[14][38] Monte Rosa was renamed HMT Empire Windrush on 21 January 1947, for use on the Southampton–Gibraltar–Suez–Aden–Colombo–Singapore–Hong Kong route, with voyages extended to Kure in Japan after the start of the Korean War. The vessel was operated for the British Government by the New Zealand Shipping Company,[8][39] and made one voyage only to the Caribbean before resuming normal trooping voyages.

West Indian immigrants

In 1948, Empire Windrush, which was en route from Australia to Britain via the Atlantic, docked in Kingston, Jamaica, to pick up servicemen who were on leave. The British Nationality Act 1948, giving the status of citizenship of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC status) to all British subjects connected with the United Kingdom or a British colony, was going through parliament, and some Caribbean migrants decided to embark "ahead of the game". Prior to 1962, the UK had no immigration control for CUKCs, who could settle indefinitely in the UK without restrictions.

The ship was far from full, and so an opportunistic advertisement was placed in a Jamaican newspaper, The Daily Gleaner, offering cheap transport on the ship for anybody who wanted to travel to the UK. Many former servicemen took this opportunity to return to Britain with the hopes of finding better employment, including, in some cases, rejoining the RAF; others decided to make the journey just to see what the "mother country" was like.[40][41] One passenger later recalled that demand for tickets far exceeded the supply, and that there was a long queue to obtain one.[42]

Passengers on board

A commonly given figure for the number of West Indian immigrants on board the Empire Windrush is 492,[2][43][44] based understandably on news reports in the media at the time, which variously announced that "more than 400", "430" or "500" Jamaican men had arrived in Britain.[45][46][47] However, the ship's records, kept in the United Kingdom National Archives, indicate conclusively that 802 passengers gave their last place of residence as a country in the Caribbean.[1] A small number of the Caribbean people on board were Indo-Caribbeans.[48]

Among West Indian passengers was Jamaican-born Sam Beaver King, who was travelling to the UK to rejoin the RAF. He would later help found the Notting Hill Carnival and become the first black Mayor of Southwark.[49] There were also the calypso musicians Lord Kitchener, Lord Beginner and Lord Woodbine, as well as Trinidadian singer Mona Baptiste, one of the few women on the ship, who had travelled first class.[50] Jamaican artist and master potter Cecil Baugh was also among the passengers.[51]

The ship also carried 66 people whose last country of residence was Mexico – they were a group of Polish people who had been detained and transported to Siberia by the Soviets after the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, but had escaped and made their way to Mexico via India and the Pacific. Around 1400 had been living at a refugee camp at Santa Rosa near León, Guanajuato since 1943.[3]

All but one of the Polish group were women and children;[3] they had been granted permission to settle in the United Kingdom under the terms of the Polish Resettlement Act 1947,[1][2][52][53][54] and the Empire Windrush had called at Tampico, Mexico to pick them up.[1] One of them later recalled they were accommodated in cabins below the waterline, only allowed on-deck in escorted groups and were kept segregated from the other passengers.[52]

Of the other passengers, 119 were from Britain and 40 from other parts of the world.[1] The non-Caribbean people on the ship included serving RAF officer, Sierra Leonean John Henry Clavell Smythe, acting as a welfare-officer; he would go on to become Attorney General of Sierra Leone.[55] Another passenger was Nancy Cunard, English writer and heiress to the Cunard shipping fortune, who was on her way back from Trinidad.[56][57]

One of the stowaways was a woman called as Evelyn Wauchope, a 39-year-old dressmaker.[58][59] She was discovered seven days out of Kingston. A whip-round was organised on board ship, raising £50 – enough for the fare and £4 pocket money for her.[56][Note 3]

Arrival

The arrival of Empire Windrush was a notable news event. Even when the ship was in the English Channel, the Evening Standard dispatched an aircraft to photograph her from the air, printing the story on the newspaper's front page.[61] The ship docked at the Port of Tilbury, near London, on 21 June 1948[43][58] and the 1,027 passengers began disembarking the next day. This was covered by newspaper reporters and by Pathé News newsreel cameras.[45] The name Windrush, as a result, has come to be used as shorthand for West Indian migration,[62] and by extension for the beginning of modern British multiracial society.

The purpose of Windrush's voyage had been to transport service personnel. The additional arrival of civilian, West Indian immigrants was not expected by the British government, and not welcome. George Isaacs, the Minister of Labour, stated in Parliament that there would be no encouragement for others to follow their example. Three days before the ship arrived, Arthur Creech Jones, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote a Cabinet memorandum noting that the Jamaican Government could not legally prevent people from departing, and the British government could not legally prevent them from landing. However, he stated that the government was opposed to this immigration, and all possible steps would be taken by the Colonial Office and the Jamaican government to discourage it.[63] Despite this, the first legislation controlling immigration was not passed until 1962.

Those who had not already arranged accommodation were temporarily housed in the Clapham South deep shelter in south-west London, less than a mile away from the Coldharbour Lane Employment Exchange in Brixton, where some of the arrivals sought work. The stowaways served brief prison sentences, but were eligible to remain in the United Kingdom on their release.[64]

Many of Empire Windrush's passengers only intended to stay for a few years but, although a number did return, the majority remained to settle permanently. Those born in the West Indies who settled in the UK in this migration movement over the following years are now typically referred to as the "Windrush Generation".[65]

Earlier voyages

While the 1948 voyage of the Windrush is well-known, it was not the first ship to carry West Indian people to the United Kingdom after World War 2. On 31 March 1947, the SS Ormonde docked at Liverpool after sailing from Jamaica with 241 passengers, including 11 stowaways. One of Ormonde's passengers was Ralph Lowe, the father of author and poet Hannah Lowe.[4] On arrival, the stowaways were tried at Liverpool Magistrates Court. The court sentenced them to one day in prison, which effectively meant their immediate release.[66]

On 21 December 1947, the SS Almanzora docked at Southampton with 200 people on board. As on the Windrush, many were former service personnel who had served in the RAF during World War 2.[4]

Later service

In May 1949, Empire Windrush was on a voyage from Gibraltar to Port Said when a fire broke out on board. Four ships were put on standby to assist if the ship had to be abandoned. Although the passengers were placed in the lifeboats, they were not launched and the ship was subsequently towed back to Gibraltar.[67]

In February 1950, the ship was used to transport the last British troops stationed in Greece back to the United Kingdom,[68] embarking the First Battalion of the Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment at Thessaloniki on 5 February, and further troops and their families at Piraeus.[69][70] British forces had been in Greece since 1944, fighting on the side of the Kingdom of Greece in the Greek Civil War.[71]

On 7 February 1953, around 200 miles (320 km) south of the Nicobar Islands, Windrush sighted a small cargo ship, the Holchu, adrift and sent out a general warning. Holchu was later boarded by the crew of a British cargo ship, the Ranee, alerted by Windrush's warning. They found no trace of the five crew and the vessel was towed to Colombo.[72] Holchu was carrying a cargo of rice and was in good condition aside from a broken mast. Adequate supplies of food, water and fuel were found, and a meal had been prepared in the ship's galley.[73] The fate of Holchu's crew remains unknown and the incident is cited in several works on Ufology and the Bermuda Triangle.[74][75][76]

In June 1953, Windrush was one of the ships that took part in the Fleet review that marked the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.[77]

Last voyage and sinking

Empire Windrush set off from Yokohama, Japan, in February 1954 on what proved to be her final voyage. She called at Kure and was to sail to the United Kingdom, calling at Hong Kong, Singapore, Colombo, Aden and Port Said.[8] Her passengers included recovering wounded United Nations veterans of the Korean War, and some soldiers from the Duke of Wellington's Regiment who had been wounded at the Third Battle of the Hook in May 1953.

The voyage was plagued with engine breakdowns and other defects, including a fire after the departure from Hong Kong.[78] It took 10 weeks to reach Port Said. There, a group of 50 Royal Marines from 3 Commando Brigade came on board and ship left port for the last time.[79][80]

On board were 222 crew and 1,276 passengers, including military personnel and some women and children, dependents of some of the military personnel.[81] With 1498 people on board, the ship was almost completely full as it was certified to carry 1541.[8]

Accidental fire

At around 6:15 am on Sunday 28 March, when the ship was in the western Mediterranean about 30 miles (48 km) north-west of Cape Caxine off the coast of Algeria,[8] there was a sudden explosion and fierce fire in the engine room which killed the third engineer, first electrician, and two other engine-room crew members; two greasers, one was the fifth man in the engine room and the other was in the boiler room, managed to escape the inferno.[8][Note 4]

The ship quickly lost all electrical power as the four main electrical generators were located in the burning engine room; the emergency backup generator was started but problems with the main circuit breaker made its power unusable. The emergency generator powered the ship's emergency lighting, bilge pump, fire pump and the radio.[8]

The ship did not have a sprinkler system. The chief officer heard the explosion from the ship's bridge and assembled the ship's firefighting squad, who happened to be on deck at the time doing routine work. They were only able to fight the fire for a few minutes before the loss of electrical power stopped the water pumps that fed their fire hoses. The second engineer was able to enter the engine room by wearing a smoke hood, but was unable to close a watertight door that might have contained the fire. Attempts to close all watertight doors using the controls on the bridge had also failed.[8]

Rescue operations

At 6:23 am, the Radio Officer sent the first distress message; this was acknowledged by two French ships, and by radio stations at Gibraltar, Oran and Algiers. Soon after, all electrical power was lost but messages continued to be sent using the emergency transmitter until 6:45am, when the fire stopped the Radio Officer from making further transmissions.[81]

The order was given to wake the passengers and crew and assemble them at their emergency stations, but the ship's public address system was not working, nor were its air and steam whistles, so the order had to be transmitted by word of mouth.

At 6:45 am, all attempts to fight the fire were halted and the order was given to launch the lifeboats, with the first ones away carrying the women and children on board[8][81] and the ship's cat.[82]

While the ship's 22 lifeboats could accommodate all on board, thick smoke and the lack of electrical power prevented many of them from being launched. Each set of lifeboat davits accommodated two lifeboats and without electrical power, raising the wire ropes to lower the second boat was an arduous and slow task. With fire spreading rapidly, the order was given to drop the remaining boats into the sea.[8] In the end, only 12 lifeboats were launched.[80]

Many of the crew and troops abandoned the ship by climbing down ladders or ropes and jumping into the sea, after first throwing overboard any loose items to hand that would float[8] Some were picked up by Windrush's lifeboats, others by a boat from the first rescue ship, which reached the scene at 7.00 am.[8][81] The last person to leave Windrush was the chief officer, Captain W Wilson, at 7:30 am.[81] Although some people were in the sea for two hours,[80] all were rescued and the only fatalities were the four crew killed in the engine room.[79]

The ships responding to Windrush's distress call were the Dutch ship MV Mentor, the British P&O Cargo liner MV Socotra, the Norwegian ship SS Hemsefjell and the Italian ships SS Taigete and SS Helschell.[83][84] A Royal Air Force Avro Shackleton from 224 Squadron assisted in the rescue.[85]

The rescue vessels took the passengers and crew to Algiers, where they were cared for by the French Red Cross and the French Army. They were taken to Gibraltar the aircraft carrier HMS Triumph. As most had lost all their possessions, the service personnel were issued with new uniforms and the families given clothing provided by SSAFA. [86] From Gibraltar, they returned to the United Kingdom in aircraft chartered from British Eagle[87] with the last group arriving on April 2nd. [88]

Salvage attempt and sinking

Around 26 hours after Empire Windrush had been abandoned, she was reached by HMS Saintes of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet 100 kilometres (54 nmi) northwest of Algiers. The fire was still burning fiercely more than a day after it started, but a party from Saintes managed to get on board and attach a tow cable. At about midday, Saintes began to tow the ship to Gibraltar, at a speed of around 3.5 knots (6.5 km/h), but Empire Windrush sank in the early hours of the following morning, Tuesday, 30 March 1954,[8] after having been towed a distance of only around 16 kilometres (8.6 nmi). The bodies of the four men killed were not recovered, and were lost when the ship sank.[89]

The wreck lies at a depth of around 2,600 m (8,500 ft).[90]

Inquiry into the sinking

An inquiry into the sinking of Empire Windrush was held in London between the 21 June and 7 July 1954.[8] John Vickers Naisby, the wreck commissioner led the enquiry.[91]

Sidney Silverman, lawyer and Member of Parliament, represented the interests of the ship's crew, and during the proceedings tried to show that Windrush was in an unsafe state and was not fit to be at sea. One of the four men killed in the accident, Engineer Leslie Pendleton, had written several letters to his father describing the ship's poor state of repair, many breakdowns, and a previous fire; these were submitted to the enquiry as evidence.[91]

No firm cause for the fire was established, but it was thought the most likely cause was that corrosion in one of the ship's funnels, or uptakes, may have led to a panel failing, causing incandescently hot soot to fall into the engine room, where it damaged a fuel oil or lubricating oil supply pipe and ignited the leaking oil.[8][92] An alternative theory was that a fuel pipe fractured and deposited fuel oil onto a hot exhaust pipe.[8] The enquiry also concluded that Windrush was seaworthy at the time she caught fire.[91]

It was thought the rapid failure of the ship's three main electrical generators was due to the fire consuming all the oxygen in the engine-room and stopping the internal combustion engines that powered them. The rapid depletion of oxygen and the fire's noxious gasses were thought to have also caused the deaths of the four engine-room crew.[8]

As the ship was government property, she was not insured.[84]

Legacy

In 1954, several of the military personnel on board Empire Windrush during her final voyage received decorations for their role in the evacuation of the burning ship. A military nurse was awarded the Royal Red Cross for her role in evacuating the patients under her care.[93]

In 1998, an area of public open space in Brixton, London, was renamed Windrush Square to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of Empire Windrush's West Indian passengers. To commemorate the "Windrush Generation", in 2008, a Thurrock Heritage plaque was unveiled at the London Cruise Terminal at Tilbury.[94] This chapter in the boat's history was also commemorated, although fleetingly only, in the Pandemonium sequence of the Opening Ceremony of the Games of the XXX Olympiad in London, 27 July 2012. A small replica of the ship plastered with newsprint was the facsimile representation in the ceremony.[95]

In 2020, a fund-raising effort was begun for a project to recover one of the ship's anchors as a monument to the people of the Windrush generation.[96][97]

See also

- MS Monte Rosa – list of ships named Monte Rosa

- Empire Orwell, formerly the German cargo liner TS Pretoria, captured and converted into a British troopship.

- SS Empire Fowey, formerly the German liner SS Potsdam, captured and converted into a British troopship.

- Windrush – a 1998 BBC documentary series about the first postwar West Indian immigrants to the UK

- Windrush Day, an annual celebration of the contribution of immigrants to British society. Held on the 22 June, the day the Empire Windrush's passengers disembarked in 1948.

- Windrush scandal, a British political scandal that began in 2018 concerning people who were wrongly detained, denied legal rights, threatened with deportation and wrongly deported from the UK by the Home Office.

Notes

- Adur, Arun, Blackwater, Bure, Calder, Clyde, Colne, Crouch, Dart, Dee, Derwent, Don, Chelmer, Cherwell, Dovey, Evenlode, Exe, Fal, Frome, Hamble, Humber, Kennet, Lune, Nene, Nidd, Orwell, Ouse, Otter, Ribble, Roden, Roding, Rother, Severn, Soar, Spey, Stour, Swale, Taff, Tamar, Taw, Tern, Teviot, Thames, Torridge, Trent, Tweed, Tyne, Usk, Wandle, Wansbeck, Waveney, Weaver, Welland, Wensum, Wey, Wharfe, Windrush, Witham, Wye, Yare.

- Naval trawlers in service with the Royal Navy also used the prefix HMT, in this case meaning His/Her Majesty's Trawler.

- Wauchope got married in Britain in 1952. In 1954, she and her husband moved to the United States.[60]

- The four killed were Senior Third Engineer George Stockwell, First Electrician J.W. Graves, Seventh Engineer A. Webster and Eighth Engineer Leslie Pendleton. Arnott (2019)

References

- Rodgers, Lucy; Maryam Ahmed (27 April 2018). "Windrush: Who exactly was on board?". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Mead, Matthew (17 October 2017). "Empire Windrush: Cultural Memory and Archival Disturbance". MoveableType. 3. doi:10.14324/111.1755-4527.027. ISSN 1755-4527.

- "The Windrush Poles: From Deportation to New Life". Culture.pl. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "Ormonde, Almanzora and Windrush". The National Archives. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- Schwerdtner, Nils (30 October 2013). German Luxury Ocean Liners: From Kaiser Willhelm to Aidastella. Amberley Publishing Limited. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-1-4456-1471-7. OCLC 832608271.

- "Lloyd's Register, Navires a Vapeur et a Moteurs" (PDF). Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. London: Lloyd's of London. 1931. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Prager, Hans Georg (1977). Blohm & Voss: ships and machinery for the world. Translated by Bishop, Frederick. Herford. p. 126. ISBN 3782201388. OCLC 32801123.

- "The Merchant Shipping Act, 1894 Report of Court (no. 7933)" (PDF). Local history & Maritime Digital Archive, Southampton City Council. 27 June 1954. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Edwards, Paul M. (28 January 2015). Small United States and United Nations Warships in the Korean War. McFarland. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-4766-2134-0.

- Mace, Martin (28 November 2014). The Royal Navy and the War at Sea 1914-1919. Pen and Sword. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-1-4738-4645-6.

- Smith, Malcolm (28 July 2014). The Royal Naval Air Service During the Great War. Pen and Sword. pp. 211–. ISBN 978-1-78346-383-1.

- "Lloyd's Register: Navires à Vapeur et à Moteurs (RHWF)" (PDF). Plimsoll Ship Data. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

- "Lloyd's Register: Navires à Vapeur et à Moteurs (DIDU)" (PDF). Plimsoll Ship Data. Retrieved 2 May 2009.

- Arnott, Paul (17 June 2019). Windrush: A Ship Through Time. History Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-0-7509-9120-9.

- Schön (2000), p.34

- Mitchell, Otis C., ed. (1981). "Karl H. Heller -- Strength through joy : regimented leisure in Nazi German". Nazism and the common man: essays in German history (1929-1939) (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-1546-1.

- James J. Barnes; Patience P. Barnes (2005). Nazis in Pre-war London, 1930-1939: The Fate and Role of German Party Members and British Sympathizers. Sussex Academic Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84519-053-8.

- "German liner aground". The Times. No. 46814. London. 23 July 1934. col F, p. 14.

- "German liner refloated". The Times. No. 46815. London. 24 July 1934. col B, p. 11.

- "D-LZ 129 "Graf Zeppelin" – Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek". www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de (in German). Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Roundups of Norwegian Jews — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Women in war : examples from Norway and beyond. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. 2015. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4724-4518-6. OCLC 921987565.

- Ottosen, Kristian (1994). "Vedlegg 1". I slik en natt; historien om deportasjonen av jøder fra Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Aschehoug. pp. 334–360. ISBN 82-03-26049-7.

- Inndragning av jødisk eiendom i Norge under den 2. verdenskrig. Norges offentlige utredninger (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statens forvaltningstjeneste. June 1997. ISBN 82-583-0437-2. NOU 1997:22 ("Skarpnesutvalget"). Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- Werner, Emmy E. (2005). A conspiracy of decency : the rescue of the Danish Jews during World War II. Boulder, Colo.: Westview. ISBN 978-0-7867-4669-9. OCLC 824698950.

- Arnott (2019), Ch.11

- Konstam, Angus (2018). Sink the Tirpitz 1942-44 : the RAF and Fleet Air Arm Duel with Germany's Mighty Battleship. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-4728-3158-3. OCLC 1057664849.

- The Official history of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Vol. 3. Toronto: University of Toronto Press in co-operation with the Dept. of National Defence and the Canadian Govt. Pub. Centre, Supply and Services Canada. 1980. pp. 458–459. ISBN 0802023797. OCLC 7596341.

- Hendrie, Andrew (1997). Canadian squadrons in Coastal Command. St. Catharines, Ont.: Vanwell. pp. 154–157. ISBN 1-55125-038-1. OCLC 38126149.

- Grove, Eric (2002). German Capital Ships and Raiders in World War II: From Scharnhorst to Tirpitz, 1942–1944. Psychology Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7146-5283-2.

- "Liner Torpedoed off Norway". The Times. No. 49820. London. 1 April 1944. p. 4.

- O'Connor, Bernard (29 June 2016). Sabotage in Norway. Lulu.com. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-291-38022-4.

- "Max Manus – leader of the Norwegian Resistance movement". Look and Learn. 12 May 1973.

- Tillotson, Michael (5 January 2012). SOE and The Resistance: As Told in The Times Obituaries. Bloomsbury. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4411-1971-1.

- Claus, Odd (2008). Vitne til krig: en norsk gutts opplevelser i Tyskland 1944–1946 [Witness to war a Norwegian boy's experiences in Germany] (in Norwegian). Oslo: Cappelen Damm. ISBN 9788204142894. OCLC 313646489.

- Miller, William H. Jr. (29 June 2012). Doomed Ships: Great Ocean Liner Disasters. Courier Corporation. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-486-14163-3.

- Schön (2000), p.55

- Schwerdtner, Nils (30 October 2013). German Luxury Ocean Liners: From Kaiser Willhelm to Aidastella. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-4456-1471-7.

- Clarkson, John (1995). New Zealand and Federal lines. Preston, U.K.: J. & M. Clarkson. p. 55. ISBN 0-9521179-5-9. OCLC 35599714.

- Phillips, Mike; Trevor Phillips (1998). Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-653039-8.

- "Windrush - Arrivals". BBC History. The Making of Modern Britain. BBC. 2001. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Gentleman, Amelia (22 June 2018). "A Windrush passenger 70 years on: 'I have no regrets about anything'". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

There were more people who wanted to travel than places available. "There was a long queue, lots of people hustling and bustling to get tickets, offering to pay more – but my name was on the list," said Gardner, now 92.

- Childs, Peter; Storry, Mike, eds. (2002). "Afro-Caribbean communities". Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture. London: Routledge. pp. 11–14.

- Cavendish, Richard (June 1998). "Arrival of SS Empire Windrush". History Today. Vol. 48, no. 6. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- "Pathe Reporter Meets". www.britishpathe.com. 24 June 1948. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- 'Empire Windrush' Ship Arrives In Uk Carrying… 1948. British Pathé, 24 June 1948.

- "500 Hope To Start a New Life Today", Daily Express, 21 June 1948. Cited in Phillips and Phillips (1998), Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain.

- "It's time to tell the stories of Windrush's Indo-Caribbean passengers". 23 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- "Sam King: Notting Hill Carnival founder and first black Southwark mayor dies". BBC News. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- Cobbinah, Angela (11 October 2018), "Mona’s musical journey after Windrush", Camden New Journal.

- Cumper, Pat (1975). "Cecil Baugh, Master Potter". Jamaica Journal. 9 (2 & 3): 18–27 – via Digital Library of the Caribbean.

- Raca, Jane (22 June 2018). "The other Windrush generation: Poles reunited after fleeing Soviet camps". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- "Who Were the Windrush Poles?". British Future. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Polish Community Focus". 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Windrush Team (5 June 2019). "The forgotten history of the Windrush". Windrush Day 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Kynaston (2007), p. 276.

- Stanley, Jo (21 June 2018). "The non-conformist heiress who sailed on the Windrush". The Morning Star. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960. Ancestry.com in association with The National Archives.

- "First Girl Stowaway". Letter in The Daily Gleaner, Thursday 5 August 1948, p. 8.

- "What became of the Windrush stowaway, Evelyn Wauchope?". 7 July 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- Richards, Denise (21 June 1948). "Welcome Home! Evening Standard 'plane greets the 400 sons of Empire". Evening Standard (36608 ed.). London. p. 1.

- "Windrush generation: Who are they and why are they facing problems?". BBC News. 31 July 2020.

- Hansen, Randall (1 June 2000). Citizenship and Immigration in Postwar Britain. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-19-158301-8.

- "Students From The Colonies". The Times. London. 9 May 1949. p. 2.

- Alexander, Saffron (22 June 2015). "Windrush Generation: 'They thought we should be planting bananas'". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Jamaicans Seeking Work In England". The Times. No. 50725. London. 2 April 1947. p. 2.

- "Troopships. Those that took us out to the Suez Canal Zone, but better still, brought us back home again". Suez Veterans Association. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- "Batallion's 25 Years Overseas". The Times. No. 51618. London. 17 February 1950. p. 8.

- "Last British Troops leave Greece". The Times. No. 51592. London. 6 February 1950. p. 5.

- "Last British Troops to Leave Greece". The Times. No. 51592. London. 17 January 1950. p. 5.

- "The Greek Civil War, 1944-1949". The National WWII Museum: New Orleans. 22 May 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- "Ship Abandoned in Indian Ocean". Townsville Daily Bulletin. 12 February 1953. p. 1.

- "Ship Found Adrift Without Crew". The Times. No. 52543. London. 11 February 1953. p. 8.

- Iturralde, Robert (27 October 2017). UFOs, Teleportation, and the Mysterious Disappearance of the Malaysian Airlines Flight #370. Robert Iturralde. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-5356-1151-0.

- Gaddis, Vincent H. (1965). Invisible Horizons: True Mysteries of the Sea. Ace Books. p. 128. OCLC 681276.

- Sanderson, Ivan (2005). Invisible Residents: The Reality of Underwater UFOs. Adventures Unlimited Press. p. 133. ISBN 1931882207. OCLC 1005460189.

- "Merchant ships at Spithead". The Times. No. 52647. London. 13 June 1953. p. 3.

- "Windrush engineer warned that ship was unsafe – archive, 1954". The Guardian. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Dockerill, Geoffrey, "On Fire at Sea" essay in compilation The Unquiet Peace: Stories from the Post War Army, London, 1957.

- "This day in 1954 - The Empire Windrush". Boat Building Academy. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- "Troopship Blaze Inquiry". The Times. No. 52964. London. 22 June 1954. p. 3.

- Makepeace, Margaret (18 August 2018). "Loss of the 'Empire Windrush'". British Library. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

Within twenty minutes of the order to abandon ship, all 250 women and children had been placed in lifeboats, as well as 500 of the servicemen and the ship's cat Tibby.

- Mitchell, W. H., and Sawyer, L. A. (1995). The Empire Ships. London, New York, Hamburg, Hong Kong: Lloyd's of London Press Ltd. p. 477. ISBN 1-85044-275-4. OCLC 246537905.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "British Troopship Ablaze In Mediterranean". The Times. No. 52982. London. 29 March 1953. p. 6.

- "Constant Endeavour". Aeroplane. No. February 2010. p. 60.

- "Ship Survivors in London". The Times. No. 52893. London. 30 March 1953. p. 6.

- "Troopship Survivors Arrive by Air". The Times. No. 52894. London. 31 March 1953. p. 8.

- "News in Brief". The Times. No. 52897. London. 3 April 1953. p. 5.

- Arnott (2019)

- "MV Empire Windrush [+1954]". wrecksite.eu. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- Arnott (2019) Chapter 23

- "Cause Of Ship's Fire Unknown". The Times. No. 52995. London. 28 July 1954. p. 5.

- "Army Nurse's Courage Rewarded". The Times. No. 53052. London. 2 October 1954. p. 3.

- "The Empire Windrush". Thurrock-history.org.uk. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Green, Miranda (26 December 2018). "Year in a word: Windrush". Financial Times. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Chakelian, Anoosh (22 June 2020). "Recovering Windrush: The deep-sea hunt for a new monument to British history". New Statesman. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Bliss, Dominic (22 June 2020). "The mission to raise the anchor from a shipwreck – as a monument to the generation it brought to Britain". National Geographic. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

Bibliography

- Sea Breeze, various contemporary issues.

- The Daily Express, 20 June 1954, for a report of the Strength Through Joy programme, archived in WO 32/15643 at The National Archives (UK) and the British Library Newspaper Library, London.

- Board of Trade Inquiry Report, archived as BT 239/56 at The National Archives.

- War Office files on the loss, archived as WO 32/15643 at The National Archives including contemporary press clippings.

- Report of the British Consul in Algiers for the Foreign Office, archived at The National Archives as FO 859/26, including recommendation to invite the Mayor of Algiers to London, an invoice for services rendered by the French Army in Algeria, a full passenger list, and letters from passengers.

- Arnott, Paul (17 June 2019). Windrush: A Ship Through Time. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-9120-9. OCLC 1091689683.

- Schön, Heinz, ed. (2000). Hitlers Traumschiffe: die "Kraft-durch-Freude"-Flotte 1934 - 1939 (in German). Kiel: Arndt. ISBN 978-3-88741-031-5.

External links

- Original blueprints of Monte Rosa by Blohm and Voss, 1931. At archive.org.

- Photographs taken onboard Monte Rosa while in passenger service with Hamburg Sud, pre-World War 2.

- Photograph of Monte Rosa in German wartime service (1943); photograph number 89096, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- 1948 voyage of the Windrush

- Passenger List from the Public Record Office

- "Windrush – the Passengers", Phillips, Mike, BBC History, 10 March 2011

- Windrush settlers arrive in Britain, 1948 – treasures of The National Archives (UK).

- Windrush settlers arrive in Britain, 1948 – Transcript

- Board of Trade 'Inwards passenger lists, 1948' Subseries within BT 26 Record Summary – held at The National Archives (UK), Kew, Richmond, London.

- Through My Eyes website Archived 7 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Imperial War Museum online exhibition – videos, pictures and interviews from the museum's archives showing the West Indian contribution to the World War II effort

- Windrush: Arrival 1948 Passenger List - Goldsmiths College, University of London

- Film by Youmanity tracing the arrival of a Jamaican family aboard Empire Windrush

- Oral history of passengers on the Windrush from BBC History

- Sinking of the Windrush

- Pathé newsreel showing the ship on fire, and the passengers and crew embarking on HMS Triumph in Algiers.