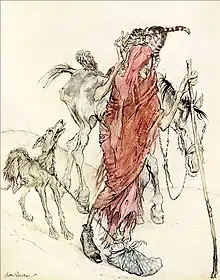

Hag

A hag is a wizened old woman, or a kind of fairy or goddess having the appearance of such a woman, often found in folklore and children's tales such as "Hansel and Gretel".[1] Hags are often seen as malevolent, but may also be one of the chosen forms of shapeshifting deities, such as The Morrígan or Badb, who are seen as neither wholly benevolent nor malevolent.[2][3]

Etymology

The term appears in Middle English, and was a shortening of hægtesse, an Old English term for 'witch'; similarly the Dutch heks and German Hexe are also shortenings, of the Middle Dutch haghetisse and Old High German hagzusa, respectively.[4] All of these words are derived from the Proto-Germanic **hagatusjon-[4] which is of unknown origin; the first element may be related to the word hedge.[4][5]

As a stock character in fairy or folk tale, the hag shares characteristics with the crone, and the two words are sometimes used as if interchangeable.

Using the word hag to translate terms found in non-English (or non-modern English) is contentious, since use of the word is sometimes associated with misogyny.[6][7]

In folklore

A "Night Hag" or "the Old Hag", was a nightmare spirit in English and anglophone North American folklore. This variety of hag is essentially identical to the Old English mæra—a being with roots in ancient Germanic superstition, and closely related to the Scandinavian mara. According to folklore, the Old Hag sat on a sleeper's chest and sent nightmares to him or her. When the subject awoke, he or she would be unable to breathe or even move for a short period of time. In the Swedish film Marianne (2011), the main character suffers from such nightmares. This state is now called sleep paralysis, but in the old belief, the subject was considered "hagridden".[8] It is still frequently discussed as if it were a paranormal state.[9]

Many stories about hags seem to have been used to frighten children into being good. In Northern England, for example, Peg Powler was a river hag who lived in the River Tees and had skin the colour of green pond scum.[10][11][12] Parents who wanted to keep their children away from the river's edge told them that if they got too close to the water, she would pull them in with her long arms, drown them, and sometimes eat them. This type of nixie or neck has other regional names, such as Grindylow[13] (a name connected to Grendel),[13][14] Jenny Greenteeth from Yorkshire, and Nelly Longarms from several English counties.[15]

Many tales about hags do not describe them well enough to distinguish between an old woman who knows magic, or a witch or supernatural being.[16]

In Slavic folklore, Baba Yaga was a hag who lived in the woods in a house on chickens legs. She would often ride through the forest on a mortar, sweeping away her tracks with a broom.[17] Though she is usually a single being, in some folktales three Baba Yagas are depicted as helping the hero in his quest, either by giving advice or by giving gifts.[18]

In Irish and Scottish mythology, the cailleach is a hag goddess concerned with creation, harvest, the weather, and sovereignty.[3][19] In partnership with the goddess Bríd, she is a seasonal goddess, seen as ruling the winter months while Bríd rules the summer.[19] In Scotland, a group of hags, known as The Cailleachan (The Storm Hags) are seen as personifications of the elemental powers of nature, especially in a destructive aspect. They are said to be particularly active in raising the windstorms of spring, during the period known as A Chailleach.[19][20]

Hags as sovereignty figures abound in Irish mythology. The most common pattern is that the hag represents the barren land, who the hero of the tale must approach without fear, and come to love on her own terms. When the hero displays this courage, love, and acceptance of her hideous side, the sovereignty hag then reveals that she is also a young and beautiful goddess.[3]

In ancient Greek religion, the Three Fates (particularly Atropos) are often depicted as hags.

Hags are similar to Lilith of the Torah and the Old Testament.

In Western literature

In mediaeval and later literature, the term hag, and its relatives in European languages, came to stand for an unattractive, older woman. Building on the mediaeval tradition of such women as portrayed in comic and burlesque literature, specifically in the Italian Renaissance, the hag represented the opposite of the lovely lady familiar from the poetry of Petrarch.[21]

In The Heroes or Greek Fairy Tales For My Children, Charles Kingsley characterized Scylla as "Scylla the sea hag".[22]

See also

References

- Briggs, Katharine. (1976) An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, "Hags", p.216. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- Lysaght, Patricia. (1986) The Banshee: The Irish Death Messenger. Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 1-57098-138-8. p.54

- Clark, Rosalind. (1991) The Great Queens: Irish Goddesses from the Morrígan to Cathleen Ní Houlihan (Irish Literary Studies, Book 34) Savage, Maryland, Barnes and Noble (reprint) pp.5, 8, 17, 25

- "Hag | Origin and meaning of hag by Online Etymology Dictionary".

- hag1 Archived 28 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition (2000)

- Rich, Adrienne (4 February 1979). "That Women Be Themselves; Women". The New York Times. pp. BR.3.

- "Feminist storyteller reprises 'These Are My Sisters'". Star Tribune. 7 July 1996.

- Ernsting, Michele (2004) "Hags and nightmares: sleep paralysis and the midnight terrors" Radio Netherlands

- The "Old Hag" Syndrome Archived 19 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine from About: Paranormal Phenomena

- Ghosts, Helpful and Harmful by Elliott O'Donnell

- Introduction to Folklore by Marian Roalfe Cox

- The History and Antiquities of the Parish of Darlington, in the Bishoprick by William Hylton Dyer Longstaffe, 1854

- The Nineteenth century and after, Volume 68, Leonard Scott Pub. Co., 1910. Page. 556

- A Grammar of the Dialect of Oldham by Karl Georg Schilling, 1906. Page. 17.

- Froud, Brian and Lee, Alan. (1978) Faeries. New York, Peacock Press ISBN 0-553-01159-6

- K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature, p 66-7 University of Chicago Press, London, 1967

- Russian Folk-Tales W. R. S. Ralston, Forgotten Books, ISBN 1-4400-7972-2, ISBN 978-1-4400-7972-6. p.170

- W. R. S. Ralston. Songs of the Russian People Section III.--Storyland Beings.

- McNeill, F. Marian (1959). The Silver Bough, Vol.2: A Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Candlemas to Harvest Home. Glasgow: William MacLellan. pp. 20–1. ISBN 978-0-85335-162-7.

- McNeill, F. Marian (1959). The Silver Bough, Vol.1: Scottish Folklore and Folk-Belief. Glasgow: William MacLellan. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-85335-161-0.

- Bettella, Patrizia (2005). The ugly woman: transgressive aesthetic models in Italian poetry from the Middle Ages to the Baroque. U of Toronto P. pp. 117–20. ISBN 978-0-8020-3926-2.

- Kingsley, Charles (1917). The Heroes or Greek Fairy Tales For my Children. Ginn and Company. pp. 148.

Further reading

- Sagan, Carl (1997) The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark.

- Kettlewell, N; Lipscomb, S; Evans, E. (1993) Differences in neuropsychological correlates between normals and those experiencing "Old Hag Attacks". Perceptual and Motor Skills 1993 Jun;76 (3 Pt 1):839-45; discussion 846. PMID 8321596

External links

- Henry Fuseli's painting of a hag, from the Met collection