Falconry

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person involved in falconry: a "falconer" flies a falcon; an "austringer" (Old French origin) flies a hawk (Accipiter, some buteos and similar) or an eagle (Aquila or similar). In modern falconry, the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), Harris's hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus), and the peregrine falcon (Falco perigrinus) are some of the more commonly used birds of prey. The practice of hunting with a conditioned falconry bird is also called "hawking" or "gamehawking", although the words hawking and hawker have become used so much to refer to petty traveling traders, that the terms "falconer" and "falconry" now apply to most use of trained birds of prey to catch game. Many contemporary practitioners still use these words in their original meaning, however.

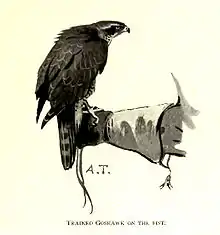

| Falconry, a living human heritage | |

|---|---|

A Goshawk | |

| Country | Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Republic of Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Morocco, Netherlands, Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Spain and Syrian Arab Republic, United Arab Emirates |

| Domains | Knowledge and practices |

| Reference | 1708 |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2021 (16th session) |

| List | Representative |

| |

In early English falconry literature, the word "falcon" referred to a female peregrine falcon only, while the word "hawk" or "hawke" referred to a female hawk. A male hawk or falcon was referred to as a "tiercel" (sometimes spelled "tercel"), as it was roughly one-third less than the female in size.[1][2] This traditional Arabian sport grew throughout Europe. Falconry is also an icon of Arabian culture. The saker falcon used by Arabs for falconry is called by Arabs "Hur" ie Free-bird where it is used in falconry since very ancient times in the Arabic peninsula. Saker Falcons are the national bird of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman and Yemen and have been integral to Arab heritage and culture for over 9,000 years. They are the national emblem of many Arabic countries.[3][4]

Birds used in contemporary falconry

Several raptors are used in falconry. They are typically classed as:

- "Broadwings": Buteo and Parabuteo spp., and eagles (red-tailed hawks, Harris hawks, golden eagles)

- "Shortwings": Accipiter (Cooper's hawk, goshawks, sparrow hawks)

- "Longwings": Falcons (peregrine falcons, kestrels, gyrfalcons, saker falcons)

Owls are also used, although they are far less common.

In determining whether a species can or should be used for falconry, the species' behavior in a captive environment, its responsiveness to training, and its typical prey and hunting habits are considered. To some degree, a species' reputation will determine whether it is used, although this factor is somewhat harder to objectively gauge.

Species for beginners

In North America, the capable red-tailed hawk is commonly flown by beginner falconers during their apprenticeship.[5][6] Opinions differ on the usefulness of the kestrel for beginners due to its inherent fragility. In the UK, beginner falconers are often permitted to acquire a larger variety of birds, but Harris's hawk and the red-tailed hawk remain the most commonly used for beginners and experienced falconers alike.[7] Red-tailed hawks are held in high regard in the UK due to the ease of breeding them in captivity, their inherent hardiness, and their capability hunting the rabbits and hares commonly found throughout the countryside in the UK. Many falconers in the UK and North America switch to accipiters or large falcons following their introduction with easier birds. In the US, accipiters, several types of buteos, and large falcons are only allowed to be owned by falconers who hold a general license. The three kinds of falconry licenses in the United States, typically, are the apprentice class, general class, and master class.

Soaring hawks and the common buzzard (Buteo)

The genus Buteo, known as "hawks" in North America and not to be confused with vultures, has worldwide distribution, but is particularly well represented in North America. The red-tailed hawk, ferruginous hawk, and rarely, the red-shouldered hawk are all examples of species from this genus that are used in falconry today. The red-tailed hawk is hardy and versatile, taking rabbits, hares, and squirrels; given the right conditions, it can catch the occasional duck or pheasant. The red-tailed hawk is also considered a good bird for beginners. The Eurasian or common buzzard is also used, although this species requires more perseverance if rabbits are to be hunted.

Harris's hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus)

Parabuteo unicinctus is one of two representatives of the Parabuteo genus worldwide. The other is the white-rumped hawk (P. leucorrhous). Arguably the best rabbit or hare raptor available anywhere, Harris's hawk is also adept at catching birds. Often captive-bred, Harris's hawk is remarkably popular because of its temperament and ability. It is found in the wild living in groups or packs, and hunts cooperatively, with a social hierarchy similar to wolves. This highly social behavior is not observed in any other bird-of-prey species, and is very adaptable to falconry. This genus is native to the Americas from southern Texas and Arizona to South America. Harris's hawk is often used in the modern technique of car hawking (or drive-by falconry), where the raptor is launched from the window of a moving car at suitable prey.

True hawks (Accipiter)

The genus Accipiter is also found worldwide. Hawk expert Mike McDermott once said, "The attack of the accipiters is extremely swift, rapid, and violent in every way." They are well known in falconry use both in Europe and North America. The northern goshawk has been trained for falconry for hundreds of years, taking a variety of birds and mammals. Other popular Accipiter species used in falconry include Cooper's hawk and the sharp-shinned hawk in North America and the European sparrowhawk in Europe and Eurasia.

Harriers (Circus)

New Zealand is likely to be one of the few countries to use a harrier species for falconry; there, falconers successfully hunt with the Australasian harrier (Circus approximans).[8]

Falcons (Falco)

The genus Falco is found worldwide and has occupied a central niche in ancient and modern falconry. Most falcon species used in falconry are specialized predators, most adapted to capturing bird prey such as the peregrine falcon and merlin. A notable exception is the use of desert falcons such the saker falcon in ancient and modern falconry in Asia and Western Asia, where hares were and are commonly taken. In North America, the prairie falcon and the gyrfalcon can capture small mammal prey such as rabbits and hares (as well as the standard gamebirds and waterfowl) in falconry, but this is rarely practiced. Young falconry apprentices in the United States often begin practicing the art with American kestrels, the smallest of the falcons in North America; debate remains on this, as they are small, fragile birds, and can die easily if neglected.[9] Small species, such as kestrels, merlins and hobbys are most often flown on small birds such as starlings or sparrows, but can also be used for recreational bug hawking – that is, hunting large flying insects such as dragonflies, grasshoppers, and moths.

Owls (Strigidae)

Owls (family Strigidae) are not closely related to hawks or falcons. Little is written in classic falconry that discusses the use of owls in falconry. However, at least two species have successfully been used, the Eurasian eagle-owl and the great horned owl.[10] Successful training of owls is much different from the training of hawks and falcons, as they are hearing- rather than sight-oriented. (Owls can only see black and white, and are long-sighted.) This often leads falconers to believe that they are less intelligent, as they are distracted easily by new or unnatural noises, and they do not respond as readily to food cues. However, if trained successfully, owls show intelligence on the same level as those of hawks and falcons.

Booted eagles (Aquila)

The Aquila (all have "booted" or feathered tarsi) genus has a nearly worldwide distribution. The more powerful types are used in falconry; for example golden eagles have reportedly been used to hunt wolves[11] in Kazakhstan, and are now most widely used by the Altaic Kazakh eagle hunters in the western Mongolian province of Bayan-Ölgii to hunt foxes,[12][13][14][15][16] and other large prey, as they are in neighbouring Kyrgyzstan.[17] Most are primarily ground-oriented, but occasionally take birds. Eagles are not used as widely in falconry as other birds of prey, due to the lack of versatility in the larger species (they primarily hunt over large, open ground), the greater potential danger to other people if hunted in a widely populated area, and the difficulty of training and managing an eagle. A little over 300 active falconers are using eagles in Central Asia, with 250 in western Mongolia, 50 in Kazakhstan, and smaller numbers in Kyrgyzstan and western China.[15]

Sea eagles (Haliaëtus)

Most species of genus Haliaëtus catch and eat fish, some almost exclusively, but in countries where they are not protected, some have been effectively used in hunting for ground quarry.

Husbandry, training, and equipment

See Hack (falconry) and Falconry training and technique. They can be trained by nurturing a deep bond between the falconer and Falcon.They should cover the falcon's head with a leather band if not hunting.

Falconry around the world

Falconry is currently practiced in many countries around the world. The falconer's traditional choice of bird is the northern goshawk and peregrine falcon. In contemporary falconry in both North America and the UK, they remain popular, although Harris' hawks and red-tailed hawks are likely more widely used. The northern goshawk and the golden eagle are more commonly used in Eastern Europe than elsewhere. In the west Asia, the saker falcon is the most traditional species flown against the houbara bustard, sandgrouse, stone-curlew, other birds, and hares. Peregrines and other captive-bred imported falcons are also commonplace. Falconry remains an important part of the Arab heritage and culture. The UAE reportedly spends over US$27 million annually towards the protection and conservation of wild falcons, and has set up several state-of-the-art falcon hospitals in Abu Dhabi and Dubai.[18] The Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital is the largest falcon hospital in the whole world. Two breeding farms are in the Emirates, as well as those in Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Every year, falcon beauty contests and demonstrations take place at the ADIHEX exhibition in Abu Dhabi.

Eurasian sparrowhawks were formerly used to take a range of small birds, but are really too delicate for serious falconry, and have fallen out of favour now that American species are available.

In North America and the UK, falcons usually fly only after birds. Large falcons are typically trained to fly in the "waiting-on" style, where the falcon climbs and circles above the falconer and/or dog and the quarry is flushed when the falcon is in the desired commanding position. Classical game hawking in the UK had a brace of peregrine falcons flown against the red grouse, or merlins in "ringing" flights after skylarks. Rooks and crows are classic game for the larger falcons, and the magpie, making up in cunning what it lacks in flying ability, is another common target. Short-wings can be flown in both open and wooded country against a variety of bird and small mammal prey. Most hunting with large falcons requires large, open tracts where the falcon is afforded opportunity to strike or seize its quarry before it reaches cover. Most of Europe practices similar styles of falconry, but with differing degrees of regulation.

Medieval falconers often rode horses, but this is now rare with the exception of contemporary Kazakh and Mongolian falconry. In Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia, the golden eagle is traditionally flown (often from horseback), hunting game as large as foxes and wolves.[20]

In Japan, the northern goshawk has been used for centuries. Japan continues to honor its strong historical links with falconry (takagari), while adopting some modern techniques and technologies.

In Australia, although falconry is not specifically illegal, it is illegal to keep any type of bird of prey in captivity without the appropriate permits. The only exemption is when the birds are kept for purposes of rehabilitation (for which a licence must still be held), and in such circumstances it may be possible for a competent falconer to teach a bird to hunt and kill wild quarry, as part of its regime of rehabilitation to good health and a fit state to be released into the wild.

In New Zealand, falconry was formally legalised for one species only, the swamp/Australasian harrier (Circus approximans) in 2011. This was only possible with over 25 years of effort from both Wingspan National Bird of Prey Center[21] and the Raptor Association of New Zealand.[22] Falconry can only be practiced by people who have been issued a falconry permit by the Department of Conservation. Tangent aspects, such as bird abatement and raptor rehabilitation, also employ falconry techniques to accomplish their goals.

Falconry today

Falcons can live into their midteens, with larger hawks living longer and eagles likely to see out middle-aged owners. Through the captive breeding of rescued birds, the last 30 years have had a great rebirth of the sport, with a host of innovations; falconry's popularity, through lure flying displays at country houses and game fairs, has probably never been higher in the past 300 years. Ornithologist Tim Gallagher, editor of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Living Bird magazine, documented his experiences with modern falconry in a 2008 book, Falcon Fever.[lower-alpha 1]

Making use of the natural relationship between raptors and their prey, falconry is now used to control pest birds and animals in urban areas, landfills, commercial buildings, hotels, and airports.[24]

Falconry centres or bird-of-prey centres house these raptors. They are responsible for many aspects of bird-of-prey conservation (through keeping the birds for education and breeding). Many conduct regular flying demonstrations and educational talks, and are popular with visitors worldwide.

Such centres may also provide falconry courses, hawk walks, displays, and other experiences with these raptors.

Clubs and organizations

In the UK, the British Falconers' Club (BFC) is the oldest and largest of the falconry clubs. BFC was founded in 1927 by the surviving members of the Old Hawking Club, itself founded in 1864. Working closely with the Hawk Board, an advisory body representing the interests of UK bird of prey keepers, the BFC is in the forefront of raptor conservation, falconer education, and sustainable falconry. Established in 1927, the BFC now has a membership over 1,200 falconers. It began as a small and elite club, but it is now a sizeable democratic organisation that has members from all walks of life, flying hawks, falcons, and eagles at legal quarry throughout the British Isles.

The North American Falconers Association[25] (NAFA), founded in 1961, is the premier club for falconry in the US, Canada, and Mexico, and has members worldwide. NAFA is the primary club in the United States and has a membership from around the world. Most USA states have their own falconry clubs. Although these clubs are primarily social, they also serve to represent falconers within their states in regards to that state's wildlife regulations.

The International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey,[26] founded in 1968, currently represents 156 falconry clubs and conservation organisations from 87 countries worldwide, totalling over 75,000 members.

The Saudi Falcons Club preserves the historical heritage associated with the falconry culture, and spreads awareness and provides training to protect falcons and flourish falconry.

Captive breeding and conservation

The successful and now widespread captive breeding of birds of prey began as a response to dwindling wild populations due to persistent toxins such as PCBs and DDT, systematic persecution as undesirable predators, habitat loss, and the resulting limited availability of popular species for falconry, particularly the peregrine falcon. The first known raptors to breed in captivity belonged to a German falconer named Renz Waller. In 1942–43, he produced two young peregrines in Düsseldorf in Germany.

The first successful captive breeding of peregrine falcons in North America occurred in the early 1970s by the Peregrine Fund, professor and falconer Heinz Meng, and other private falconer/breeders such as David Jamieson and Les Boyd who bred the first peregrines by means of artificial insemination. In Great Britain, falconer Phillip Glasier of the Falconry Centre in Newent, Gloucestershire, was successful in obtaining young from more than 20 species of captive raptors. A cooperative effort began between various government agencies, non-government organizations, and falconers to supplement various wild raptor populations in peril. This effort was strongest in North America where significant private donations along with funding allocations through the Endangered Species Act of 1972 provided the means to continue the release of captive-bred peregrines, golden eagles, bald eagles, aplomado falcons and others. By the mid-1980s, falconers had become self-sufficient as regards sources of birds to train and fly, in addition to the immensely important conservation benefits conferred by captive breeding.

Between 1972 and 2001, nearly all peregrines used for falconry in the U.S. were captive-bred from the progeny of falcons taken before the U. S. Endangered Species Act was passed, and from those few infusions of wild genes available from Canada and special circumstances. Peregrine falcons were removed from the United States' endangered species list on August 25, 1999.[27] Finally, after years of close work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, a limited take of wild peregrines was allowed in 2001, the first wild peregrines taken specifically for falconry in over 30 years.

Some controversy has existed over the origins of captive-breeding stock used by the Peregrine Fund in the recovery of peregrine falcons throughout the contiguous United States. Several peregrine subspecies were included in the breeding stock, including birds of Eurasian origin. Due to the extirpation of the eastern subspecies (Falco peregrinus anatum), its near extirpation in the Midwest, and the limited gene pool within North American breeding stock, the inclusion of non-native subspecies was justified to optimize the genetic diversity found within the species as a whole.[28] Such strategies are common in endangered species reintroduction scenarios, where dramatic population declines result in a genetic bottleneck and the loss of genetic diversity.

Laws regulating the hunting, import and export of wild falcons vary across Asia, and effective enforcement of current national and international regulations is lacking in some regions. It is possible that the spread of captive-bred falcons in falcon markets in the Arabian Peninsula has mitigated this demand for wild falcons.

Hybrid falcons

The species within the genus Falco are closely related, and some pairings produce viable offspring. The heavy northern gyrfalcon and Asiatic saker are especially closely related, and whether the Altai falcon is a subspecies of the saker or descendants of naturally occurring hybrids is not known. Peregrine and prairie falcons have been observed breeding in the wild and have produced offspring.[29] These pairings are thought to be rare, but extra-pair copulations between closely related species may occur more frequently and/or account for most natural occurring hybridization. Some male first-generation hybrids may have viable sperm, whereas very few first-generation female hybrids lay fertile eggs. Thus, naturally occurring hybridization is thought to be somewhat insignificant to gene flow in raptor species.

The first hybrid falcons produced in captivity occurred in western Ireland when veteran falconer Ronald Stevens and John Morris put a male saker and a female peregrine into the same moulting mews for the spring and early summer, and the two mated and produced offspring.

Captive-bred hybrid falcons have been available since the late 1970s, and enjoyed a meteoric rise in popularity in North America and the UK in the 1990s. Hybrids were initially "created" to combine the horizontal speed and size of the gyrfalcon with the good disposition and aerial ability of the peregrine. Hybrid falcons first gained large popularity throughout the Arabian Peninsula, feeding a demand for particularly large and aggressive female falcons capable and willing to take on the very large houbara bustard, the classic falconry quarry in the deserts of the West Asia. These falcons were also very popular with Arab falconers, as they tended to withstand a respiratory disease (aspergillosis from the mold genus Aspergillus) in stressful desert conditions better than other pure species from the Northern Hemisphere.

Artificial selection and domestication

Some believe that no species of raptor have been in captivity long enough to have undergone successful selective breeding for desired traits. Captive breeding of raptors over several generations tends to result, either deliberately, or inevitably as a result of captivity, in selection for certain traits, including:

- Ability to survive in captivity

- Ability to breed in captivity

- Suitability (in most cases) for interactions with humans for falconry: Birds that demonstrated an unwillingness to hunt with men were most often discarded, rather than being placed in breeding projects

- With gyrfalcons in areas away from their natural Arctic tundra habitat, better disease resistance

- With gyrfalcons, feather color[30]

Escaped falconry birds

Falconers' birds are inevitably lost on occasion, though most are found again. The main reason birds can be found again is because, during free flights, birds usually wear radio transmitters or bells. The transmitters are in the middle of the tail, on the back, or attached to the bird's legs.

Records of species becoming established in Britain after escaping or being released include:

- Escaped Harris hawks reportedly bred in the wild in Britain.

- The return of the goshawk as a breeding bird to Britain since 1945 is due in large part to falconers' escapes; the earlier British population was wiped out by gamekeepers and egg collectors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- A pair of European eagle owls bred in the wild in Yorkshire for several years, feeding largely or entirely on rabbits. The pair are most likely captive escapees. If this will lead to a population becoming established is not yet known.

In 1986, a lost captive-bred female prairie falcon (which had been cross-fostered by an adult peregrine in captivity) mated with a wild male peregrine in Utah. The prairie falcon was trapped and the eggs removed, incubated, and hatched, and the hybrid offspring were given to falconers. The wild peregrine paired with another peregrine the next year.

Falconry in Hawaii is prohibited largely due to the fears of escaped non-native birds of prey becoming established on the island chain and aggravating an already rampant problem of invasive species impacts on native wildlife and plant communities.

Regulations

In Great Britain

In sharp contrast to the US, falconry in Great Britain is permitted without a special license, but a restriction exists of using only captive-bred birds. In the lengthy, record-breaking debates in Westminster during the passage of the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Bill, efforts were made by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and other lobby groups to have falconry outlawed, but these were successfully resisted. After a centuries-old but informal existence in Britain, the sport of falconry was finally given formal legal status in Great Britain by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which allowed it to continue, provided all captive raptors native to the UK were officially ringed and government-registered. DNA testing was also available to verify birds' origins. Since 1982, the British government's licensing requirements have been overseen by the Chief Wildlife Act Inspector for Great Britain, who is assisted by a panel of unpaid assistant inspectors.

British falconers are entirely reliant upon captive-bred birds for their sport. The taking of raptors from the wild for falconry, although permitted by law under government licence, has not been allowed in recent decades.

Anyone is permitted to possess legally registered or captive-bred raptors, although falconers are anxious to point out this is not synonymous with falconry, which specifically entails the hunting of live quarry with a trained bird. A raptor kept merely as a pet or possession, although the law may allow it, is not considered to be a falconer's bird. Birds may be used for breeding or kept after their hunting days are over, but falconers believe it is preferable that young, fit birds are flown at quarry.

In the United States

In the United States, falconry is legal in all states except Hawaii, and in the District of Columbia. A falconer must have a state permit to practice the sport. (Requirements for a federal permit were changed in 2008 and the program discontinued effective January 1, 2014.)[31] Acquiring a falconry license in the United States requires an aspiring falconer to pass a written test, have equipment and facilities inspected, and serve a minimum of two years as an apprentice under a licensed falconer, during which time, the apprentice falconer may only possess one raptor. Three classes of the falconry license have a permit issued jointly by the falconer's state of residence and the federal government. The aforementioned apprentice license matriculates to a general class license, which allows the falconer to up to three raptors at one time. (Some jurisdictions may further limit this.) After a minimum of five years at general level, falconers may apply for a master class license, which allows them to keep up to five wild raptors for falconry and an unlimited number of captive-produced raptors. (All must be used for falconry.) Certain highly experienced master falconers may also apply to possess golden eagles for falconry.

Within the United States, a state's regulations are limited by federal law and treaties protecting raptors. Most states afford falconers an extended hunting season relative to seasons for archery and firearms, but species to be hunted, bag limits, and possession limits remain the same for both. No extended seasons for falconry exist for the hunting of migratory birds such as waterfowl and doves.

Federal regulation of falconry in North America is enforced under the statutes of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), originally designed to address the rampant commercial market hunting of migratory waterfowl during the early 20th century. Birds of prey suffered extreme persecution from the early 20th century through the 1960s, where thousands of birds were shot at conspicuous migration sites, and many state wildlife agencies issued bounties for carcasses.[32] Due to widespread persecution and further impacts to raptor populations from DDT and other toxins, the act was amended in 1972 to include birds of prey. (Eagles are also protected under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1959.) Under the MBTA, taking migratory birds, their eggs, feathers, or nests is illegal. Take is defined in the MBTA to "include by any means or in any manner, any attempt at hunting, pursuing, wounding, killing, possessing, or transporting any migratory bird, nest, egg, or part thereof".[33] Falconers are allowed to trap and otherwise possess certain birds of prey and their feathers with special permits issued by the Migratory Bird Office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and by state wildlife agencies (issuers of trapping permits).

The Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) restricts the import and export of most native birds species and are listed in the CITES Appendices I, II, and III.

The Wild Bird Conservation Act, legislation put into effect circa 1993, regulates importation of any CITES-listed birds into the United States.

Some controversy exists over the issue of falconer's ownership of captive-bred birds of prey. Falconry permits are issued by states in a manner that entrusts falconers to "take" (trap) and possess permitted birds and use them only for permitted activities, but does not transfer legal ownership. No legal distinction is made between native wild-trapped vs. captive-bred birds of the same species. This legal position is designed to discourage the commercial exploitation of native wildlife.

History

Evidence suggests that the art of falconry may have begun in Mesopotamia, with the earliest accounts dating to around 2,000 BC. Also, some raptor representations are in the northern Altai, western Mongolia.[2][34] The falcon was a symbolic bird of ancient Mongol tribes.[35] Some disagreement exists about whether such early accounts document the practice of falconry (from the Epic of Gilgamesh and others) or are misinterpreted depictions of humans with birds of prey.[36][37] During the Turkic Period of Central Asia (seventh century AD), concrete figures of falconers on horseback were described on the rocks in Kyrgyz.[34] Falconry was probably introduced to Europe around AD 400, when the Huns and Alans invaded from the east. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194–1250) is generally acknowledged as the most significant wellspring of traditional falconry knowledge. He is believed to have obtained firsthand knowledge of Arabic falconry during wars in the region (between June 1228 and June 1229). He obtained a copy of Moamyn's manual on falconry and had it translated into Latin by Theodore of Antioch. Frederick II himself made corrections to the translation in 1241, resulting in De Scientia Venandi per Aves.[38] King Frederick II is most recognized for his falconry treatise, De arte venandi cum avibus (The Art of Hunting with Birds). Written himself toward the end of his life, it is widely accepted as the first comprehensive book of falconry, but also notable in its contributions to ornithology and zoology. De arte venandi cum avibus incorporated a diversity of scholarly traditions from east to west, and is one of the earliest challenges to Aristotle's explanations of nature.[39]

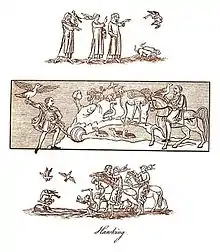

Historically, falconry was a popular sport and status symbol among the nobles of medieval Europe,[41] and Asia. Many historical illustrations left in Rashid al Din's "Compendium chronicles" book described falconry of the middle centuries with Mongol images. Falconry was largely restricted to the noble classes due to the prerequisite commitment of time, money, and space. In art and other aspects of culture, such as literature, falconry remained a status symbol long after it was no longer popularly practiced. The historical significance of falconry within lower social classes may be underrepresented in the archaeological record, due to a lack of surviving evidence, especially from nonliterate nomadic and nonagrarian societies. Within nomadic societies such as the Bedouin, falconry was not practiced for recreation by noblemen. Instead, falcons were trapped and hunted on small game during the winter to supplement a very limited diet.[42]

In the UK and parts of Europe, falconry probably reached its zenith in the 17th century,[1][2] but soon faded, particularly in the late 18th and 19th centuries, as firearms became the tool of choice for hunting. (This likely took place throughout Europe and Asia in differing degrees.) Falconry in the UK had a resurgence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when a number of falconry books were published.[43] This revival led to the introduction of falconry in North America in the early 20th century. Colonel R. Luff Meredith is recognized as the father of North American falconry.[44]

Throughout the 20th century, modern veterinary practices and the advent of radio telemetry (transmitters attached to free-flying birds) increased the average lifespan of falconry birds, and allowed falconers to pursue quarry and styles of flight that had previously resulted in the loss of their hawk or falcon.

Timeline

- 722–705 BC – An Assyrian bas-relief found in the ruins at Khorsabad during the excavation of the palace of Sargon II (Sargon II) has been claimed to depict falconry. In fact, it depicts an archer shooting at raptors and an attendant capturing a raptor. A. H. Layard's statement in his 1853 book Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon is "A falconer bearing a hawk on his wrist appeared to be represented in a bas-relief which I saw on my last visit to those ruins."

- 680 BC – Chinese records describe falconry.

- Fourth century BC – Aristotle wrote that in Thrace, the boys who want to hunt small birds, take hawks with them. When they call the hawks addressing them by name, the hawks swoop down on the birds. The small birds fly in terror into the bushes, where the boys catch them by knocking them down with sticks; in case the hawks themselves catch any of the birds, they throw them down to the hunters. When the hunting finishes, the hunters give a portion of all that is caught to the hawks.[45] He also wrote that in the city of Cedripolis (Κεδρίπολις), men and hawks jointly hunt small birds. The men drive them away with sticks, while the hawks pursue closely, and the small birds in their flight fall into the clutches of the men. Because of this, they share their prey with the hawks.[46]

- Third century BC – Antigonus of Carystus wrote the same story about the city of Cedripolis.[47]

- 355 AD – Nihon-shoki, a largely mythical narrative, records hawking first arriving in Japan from Baekje as of the 16th emperor Nintoku.

- Second–fourth century – the Germanic tribe of the Goths learned falconry from the Sarmatians.

- Fifth century – the son of Avitus, Roman Emperor 455–56, from the Celtic tribe of the Arverni, who fought at the Battle of Châlons with the Goths against the Huns, introduced falconry in Rome.

- 500 – a Roman floor mosaic depicts a falconer and his hawk hunting ducks.

- Early seventh century – Prey caught by trained dogs or falcons is considered halal in Quran.[48] By this time, falconry was already popular in the Arabian Peninsula.

- 818 – Japanese Emperor Saga ordered someone to edit a falconry text named Shinshuu Youkyou.

- 875 – Western Europe and Saxon England practiced falconry widely.

- 991 – In the poem The Battle of Maldon describing the Battle of Maldon in Essex, before the battle, the Anglo-Saxons' leader Byrhtnoth says, "let his tame hawk fly from his hand to the wood".

- 1070s – The Bayeux Tapestry shows King Harold of England with a hawk in one scene. The king is said to have owned the largest collection of books on the sport in all of Europe.

- 1100 – Norman nobility distinguished falconry from the sport of 'hawking'.[41] Normans practiced falconry by horseback and 'hawking' by foot.[41]

- Around 1182 – Niketas Choniates wrote about hawks that are trained to hunt at the Byzantine Empire.[49]

- Around the 1240s – The treatise of an Arab falconer, Moamyn, was translated into Latin by Master Theodore of Antioch, at the court of Frederick II, it was called De Scientia Venandi per Aves and much copied.

- 1250 – Frederick II wrote in the last years of his life a treatise on the art of hunting with birds: De arte venandi cum avibus.

- 1285 – The Baz-Nama-yi Nasiri, a Persian treatise on falconry, was compiled by Taymur Mirza, an English translation of which was produced in 1908 by D. C. Phillott.[50]

- 1325 – The Libro de la caza, by the prince of Villena, Don Juan Manuel, includes a detailed description of the best hunting places for falconry in the kingdom of Castile.

- 1390s – In his Libro de la caza de las aves, Castilian poet and chronicler Pero López de Ayala attempts to compile all the available correct knowledge concerning falconry.

- 1486 – See the Boke of Saint Albans

- Early 16th century – Japanese warlord Asakura Norikage (1476–1555) succeeded in captive breeding of goshawks.

- 1580s – Spanish drawings of Sambal people recorded in the Boxer Codex showed a culture of falconry in the Philippines.

- 1600s – In Dutch records of falconry, the town of Valkenswaard was almost entirely dependent on falconry for its economy.

- 1660s – Tsar Alexis of Russia writes a treatise that celebrates aesthetic pleasures derived from falconry.

- 1801 – Joseph Strutt of England writes, "the ladies not only accompanied the gentlemen in pursuit of the diversion [falconry], but often practiced it by themselves; and even excelled the men in knowledge and exercise of the art."

- 1864 – The Old Hawking Club is formed in Great Britain.

- 1921 – Deutscher Falkenorden is founded in Germany. Today, it is the largest and oldest falconry club in Europe.

- 1927 – The British Falconers' Club is founded by the surviving members of the Old Hawking Club.

- 1934 – The first US falconry club, the Peregrine Club of Philadelphia, is formed; it became inactive during World War II and was reconstituted in 2013 by Dwight A. Lasure of Pennsylvania.

- 1941 – Falconer's Club of America formed

- 1961 – Falconer's Club of America was defunct

- 1961 – North American Falconers Association formed

- 1968 – International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey formed[51]

- 1970 – Peregrine falcons were listed as an endangered species in the U.S., due primarily to the use of DDT as a pesticide (35 Federal Register 8495; June 2, 1970).

- 1970 – The Peregrine Fund is founded, mostly by falconers, to conserve raptors, and focusing on peregrine falcons.

- 1972 – DDT banned in the U.S. (EPA press release – December 31, 1972) but continues to be used in Mexico and other nations.

- 1999 – Peregrine falcon removed from the Endangered Species List in the United States, due to reports that at least 1,650 peregrine breeding pairs existed in the U.S. and Canada at that time. (64 Federal Register 46541-558, August 25, 1999)

- 2003 – A population study by the USFWS shows peregrine falcon numbers climbing ever more rapidly, with well over 3000 pairs in North America

Hunting falcon as depicted by Edwin Henry Landseer in 1837.

Hunting falcon as depicted by Edwin Henry Landseer in 1837. - 2006 – A population study by the USFWS shows peregrine falcon numbers still climbing. (Federal Register circa September 2006)

- 2008 – USFWS rewrites falconry regulations virtually eliminating federal involvement. {Federal Register: October 8, 2008 (Volume 73, Number 196)}

- 2010 – Falconry is added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)[19][52]

Falconry in Britain in early 12th century

Medieval Normans distinguished falconry from the sport of 'hawking'.[41] Normans practiced falconry by horseback and 'hawking' by foot.[41] An immediate impact of the Norman Conquest of England was a penchant for falconry enjoyed by Norman nobility.[41] So much so, in fact, that they outlawed commoners from hunting particular lands so that nobility could freely enjoy both sports.[41] Both falconry and 'hawking' were central to Norman cultural identity in medieval times.[41] Normans transported their falcons on a frame called a cadge.[41]

The Book of St Albans

The often-quoted Book of Saint Albans or Boke of St Albans, first printed in 1486, often attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, provides this hierarchy of hawks and the social ranks for which each bird was supposedly appropriate.

- Emperor: Eagle, vulture, and merlin

- King: gyr falcon and the tercel of the gyr falcon

- Prince: falcon gentle and the tercel gentle

- Duke: falcon of the loch

- Earl: Peregrine falcon

- Baron: bustard

- Knight: sacre and the sacret

- Esquire: lanere and the laneret

- Lady: marlyon

- Young man: hobby

- Yeoman: goshawk

- Poor man: tercel

- Priest: sparrowhawk

- Holy water clerk: musket

- Knave or servant: kestrel

This list, however, was mistaken in several respects.

- 1) Vultures are not used for falconry.

- 3) 4) 5) These are usually said to be different names for the peregrine falcon. But there is an opinion that renders 4) as "rock falcon" = a peregrine from remote rocky areas, which would be bigger and stronger than other peregrines. This could also refer to the Scottish peregrine.

- 6) The bustard is not a bird of prey, but a game species that was commonly hunted by falconers; this entry may have been a mistake for buzzard, or for busard which is French for "harrier"; but any of these would be a poor deal for barons; some treat this entry as "bastard hawk", possibly meaning a hawk of unknown lineage, or a hawk that could not be identified.

- 7) Sakers were imported from abroad and very expensive, and ordinary knights and squires would be unlikely to have them.

- 8) Contemporary records have lanners as native to England.

- 10) 15) Hobbies and kestrels are historically considered to be of little use for serious falconry (the French name for the hobby is faucon hobereau, hobereau meaning local/country squire. That may be the source of the confusion), however King Edward I of England sent a falconer to catch hobbies for his use. Kestrels are coming into their own as worthy hunting birds, as modern falconers dedicate more time to their specific style of hunting. While not suitable for catching game for the falconer's table, kestrels are certainly capable of catching enough quarry that they can be fed on surplus kills through the molt.

- 12) An opinion[53] holds that since the previous entry is the goshawk, this entry ("Ther is a Tercell. And that is for the powere [= poor] man.") means a male goshawk and that here "poor man" means not a labourer or beggar, but someone at the bottom of the scale of landowners.

The relevance of the "Boke" to practical falconry past or present is extremely tenuous, and veteran British falconer Phillip Glasier dismissed it as "merely a formalised and rather fanciful listing of birds".

Falconry in Britain in 1973

A book about falconry published in 1973[54] says:

- Most falconry birds used in Britain were taken from the wild, either in Britain, or taken abroad and then imported.

- Captive breeding was initiated. The book mentions a captive-bred goshawk and a brood of captive-bred red-tailed hawks. It describes as a new and remarkable event captive breeding hybrid young in 1971 and 1972 from John Morris's female saker and Ronald Stevens's peregrine falcon.

- Peregrine falcons were suffering from the post–World War II severe decline caused by pesticides. Taking wild peregrines in Britain was only allowed to train them to keep birds off Royal Air Force airfields to prevent bird strikes.

- The book does not mention telemetry.

- Harris hawks were known to falconers but unusual. For example, the book lists a falconry meet on four days in August 1971 at White Hill and Leafield in Dumfriesshire in Scotland; the hawks flown were 11 goshawks and one Harris hawk. The book felt it necessary to say what a Harris hawk is.

- The usual species for a beginner was a kestrel.

- A few falconers used golden eagles.

- Falcons in falconry would have bells on their legs so the hunters could find them. If the bells fell off the falcon, the hunter would not be able to find his bird easily. The bird usually died if it could not find a way to remove the leather binding on its feet.

Intangible cultural heritage

In 2010, UNESCO inscribed falconry as a living human heritage element of 11 countries, including the United Arab Emirates, Belgium, Czech Republic, Slovakia, France, Republic of Korea, Mongolia, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Spain, and the Syrian Arab Republic. Austria and Hungary were added in 2012, and Germany, Italy, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, and Portugal were added in 2016. With a total of eighteen countries, falconry is the largest multi-national nomination on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[55]

Literature and film

- In historic literature of Mongols, The Secret History of Mongol is one of earliest books that described Bodonchar Munkhag, first leader of the Borjigan tribe as having first caught a falcon and fed it until spring. Through falconry, he not only survived, but also made it his tribal custom. His eighth-generation descendant Esukhei Baatar (hereo) was also in falconry, and he was the father of Genghis Khan. Through Genghis Khan's Great Mongol empire, this custom was introduced to China, Korea, Japan, and Europe, as well as the Western Asia.

- In the Tale XXXIII of the Tales of Count Lucanor by the prince of Villena, Lo que sucedió a un halcón sacre del infante don Manuel con una garza y un águila, the tale tries to teach a moral based on a story about falconry lived by the father of the author.

- In the ninth novel of the fifth day of Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron, a medieval collection of novellas, a falcon is central to the plot: Nobleman Federigo degli Alberighi has wasted his fortune courting his unrequited love until nothing is left but his brave falcon. When his lady comes to see him, he gives her the falcon to eat. Knowing his case, she changes her mind, marries him, and makes him rich.

- Famous explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton wrote an account of falconry in India, Falconry in the Valley of the Indus, first published in 1852 and now available in modern reprints.

- A 17th-century English physician-philosopher, Sir Thomas Browne, wrote a short essay on falconry.[56]

- T.H. White was a falconer and wrote The Goshawk about his attempt to train a hawk in the traditional art of falconry. Falconry is also featured and discussed in The Once and Future King.

- In Virginia Henley's historical romance books, The Falcon and the Flower, The Dragon and the Jewel, The Marriage Prize, The Border Hostage, and Infamous, numerous mentions to the art of falconry are made, as these books are set at dates ranging from the 1150s to the 16th century.

- The main character, Sam Gribley, in the children's novel My Side of the Mountain, is a falconer. His trained falcon is named Frightful.

- William Bayer's novel Peregrine set in the world of falconry, about a rogue peregrine falcon in New York City, won the 1982 Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Mystery.

- Stana Katic, the Canadian actress who played Detective Kate Beckett on Castle, enjoys falconry in her spare time.[57] She has said that "It gives me self-respect."

- In the book and movie The Falcon and the Snowman about two Americans who sold secrets to the Soviets, one of the two main characters, Christopher Boyce, is a falconer.

- In The Royal Tenenbaums, Richie keeps a falcon named Mordecai on the roof of his home in Brooklyn.

- In James Clavell's Shōgun, Toranaga, one of the main characters, practices falconry throughout the book, often during or immediately before or after important plot events. His thoughts also reveal an analogy between his falconry and his use of other characters towards his ends.

- The 1985 film Ladyhawke involved a medieval warrior who carried a red-tailed hawk as a pet, but in truth, the hawk was actually his lover, who had been cursed by an evil bishop to keep the two apart.

- In The Dark Tower series, the main character, Roland, uses a hawk named David, to win a trial by combat to become a Gunslinger.

- "The Falconer" is a recurring sketch on Saturday Night Live, featuring Will Forte as a falconer who constantly finds himself in mortal peril and must rely on his loyal falcon, Donald, to rescue him.

- Gabriel García Márquez's novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold's main character, Santiago Nasar, and his father are falconers.

- Hodgesaargh is a falconer based in Lancre Castle in Terry Pratchett's Discworld books. He is an expert and dedicated falconer who unluckily seems to only keep birds that enjoy attacking him.

- Fantasy author Mercedes Lackey is a falconer and often adds birds of prey to her novels. Among the Tayledras or Hawkbrother race in her Chronicles of Valdemar, everyone bonds with a specially bred raptor called a bondbird, which has limited powers of speech mind-to-mind and can scout and hunt for its human bondmate.

- Crime novelist Andy Straka is a falconer and his Frank Pavlicek private eye series features a former NYPD homicide detective and falconer as protagonist. The books include A Witness Above, A Killing Sky, Cold Quarry (2001, 2002, 2003), and Kitty Hitter (2009).

- In Irish poet William Butler Yeats's poem, "The Second Coming", Yeats uses the image of "The falcon cannot hear the falconer" as a metaphor for social disintegration.

- American poet Robert Duncan's poem "My Mother Would Be a Falconress"[58]

- The comic book Gold Ring by Qais M. Sedki and Akira Himekawa features falconers and falcons.

- The Marvel Comics character The Falcon is both named after the animal, but is a falconer himself, fighting crime with his falcon Redwing.

- C. J. Box's Joe Pickett series of novels has a recurring character, Nate Romanowski, who is a falconer.

- A Kestrel for a Knave is a novel by British author Barry Hines, published in 1968. It is set in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, and tells of Billy Casper, a young working-class boy troubled at home and at school, who only finds solace when he finds and trains a kestrel, which he names "Kes". The film made from the book in 1969 by Ken Loach is also called Kes.

- Barry Hines was inspired by his younger brother Richard, who like Billy Casper, took kestrels from the wild and trained them. (He trained the three hawks used in the film Kes.) He has written of this in his memoir No Way But Gentleness: A Memoir of How Kes, My Kestrel, Changed My Life (Bloomsbury, 2016).

- H is for Hawk (Vintage, 2015) by Helen Macdonald, which won the Samuel Johnson Prize and Costa Book of the Year prizes in 2014, tells of how she trained a goshawk and mourned her father in the same year. It has echoes of T.H. White's The Goshawk.

- Dragonheart features Brok, the brutal knight for the iron fisted King Einon, who proved a capable falconer and owns a falcon.

- On The Mummy Returns, Ardeth Bay proved a capable falconer and owned a saker falcon named after the Egyptian god Horus. Sadly, while delivering a message, Horus was shot to death by Lock-Nah with a rifle.

- Avatar: The Last Airbender featured falconry, involving many using messenger hawks to deliver messages. Also the assassin, Combustion Man showed talents with falconry. owned a raven eagle, which he used to intercept a messenger hawk carrying information about Aang's whereabouts. The raven eagle tied the hawk up, stole the message it was carrying, and delivered it to Combustion Man, thus keeping the Avatar's survival after the Coup of Ba Sing Se a secret.

English language words and idioms derived from falconry

These English language words and idioms are derived from falconry:

| Expression | Meaning in falconry | Derived meaning |

|---|---|---|

| haggard[59] | of a hawk, caught from the wild when adult | looking exhausted and unwell, in poor condition; wild or untamed |

| lure[60] | Originally a device used to recall hawks. The hawks, when young, were trained to associate the device (usually a bunch of feathers) with food. | To tempt with a promise/reward/bait |

| rouse[61] | To shake one's feathers | Stir or awaken |

| pounce[62] | Referring to a hawk's claws, later derived to refer to birds springing or swooping to catch prey | Jump forward to seize or attack something |

| to turn tail[63] | Fly away | To turn and run away |

See also

Notes

- About 5,000 falconers were in the United States in 2008.[23]

References

- Bert, E. (1619), An Approved Treatise on Hawks and Hawking.

- Latham, S. (1633), The Falcon's Lure and Cure.

- "Why peregrine falcons are the ultimate status symbol in the Middle East". The Telegraph.

- "Saker Falcon entry at Abu Dhabi Environment division".

- "The Modern Apprentice – The Red-Tail Hawk". Themodernapprentice.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Beginners Circle". Americanfalconry.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Harris' Hawk". DK: Cyber city. Archived from the original on 2013-03-05. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- "Falconry". NZ Falconers Association. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Should Apprentice Falconers be Allowed to Fly American Kestrels?". American falconry. 1992-04-14. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- Melling, T.; Dudley, S. & Doherty, P. (2008). "The Eagle Owl in Britain" (PDF). British Birds. 101 (9): 478–490.

- Hollinshead, Martin (2006), The last Wolf Hawker: The Eagle Falconry of Friedrich Remmler, The Fernhill Press, archived from the original on 2011-09-28, retrieved 2007-06-21.

- "International Journal of Intangible Heritage". International Journal of Intangible Heritage. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-17. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Eagle Hunters". Discover-bayanolgii.com. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "International Journal of Intangible Heritage". International Journal of Intangible Heritage. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Stewart, Rowan (2002), Kyrgyzstan, Odyssey, p. 182.

- UAEINTERACT. "UAE Interact, United Arab Emirates information, news, photographs, maps and webcams". Uaeinteract.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "A Falconer with His Falcon near Al-Ain". World Digital Library. 1965. Archived from the original on 2016-05-25. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- "Kyrgyz berkut, kyrgyz hunting eagle". Pipex. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- "Wingspan National Bird of Prey Center". NZ. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "Raptor Association". NZ. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- "Tim Gallagher's got "Falcon Fever"" (Blog spot). Wild Bird on the Fly (World Wide Web log). Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

- Ranahan, Jared (28 January 2022). "Preying for a paycheck: The birds that work for hotels". The Washington Post.

- "North American Falconers Association". N-a-f-a.com. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey – Home". Iaf.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Peregrine Falcons". Endangered Species Program. US Fish & Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Cade, TJ; Burnham, W (2003), The Return of the Peregrine: a North American sage of tenacity and teamwork, The Peregrine Fund.

- Oliphant, LW (1991), "Hybridization Between a Peregrine Falcon and a Prairie Falcon in the Wild.", The Journal of Raptor Research, 25 (2): 36–39.

- "Welcome to Canada's oldest and most successful gyrfalcon breeding establishment". Archived from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- "73 FR 59448" (PDF). Gpo.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-31. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Matthiessen, P (1959), Wildlife in America, Viking.

- "Migratory Bird Treaty Act". Archived from the original on 2010-12-03. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- "The Asian Conference on the Social Sciences (ACSS)" (PDF). ACSS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). www.mefrg.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Epic of Gilgamesh.

- Layard, A. H. (1853), Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, London: John Murray.

- Egerton, F (2003), "A History of the Ecological Sciences : Part 8: Fredrick II of Hohenstaufen: Amateur Avian Ecologist and Behaviorist" (PDF), Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, Esa pubs, 84 (1): 40–44, doi:10.1890/0012-9623(2003)84[40:ahotes]2.0.co;2, archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-11-27, retrieved 2007-11-03.

- Ferber, S (1979), Islam and The Medieval West.

- Strutt, Joseph (1801). Cox, J. Charles (ed.). The sports and pastimes of the people of England from the earliest period. Methuen & co. p. 24. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- 15 Let's play Age of Empires IV. Falconry & Hawking: Norman Nobility.

- Thesiger, W (1959), Arabian Sands, Penguin Books.

- Mitchell, EB (1971) [1900], The art & practice of hawking (7th ed.), Newton, MA: Charles T. Branford, p. 291

- A brief history of North American Falconry, NAFA, archived from the original on 2015-04-08.

- "Aristotelian Corpus, On Marvelous Things Heard, 27.118". Archived from the original on 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Aristotle, History of Animals, 9.36.2". Archived from the original on 2020-10-09. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- "Antigonus, Compilation of Marvellous Accounts, 28". Archived from the original on 2020-03-06. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- Quran 5:4.

- "Niketas Choniates, Annals, 251". Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- The Baz-Nama-Yi Nasiri. A Persian Treatise on Falconry. Translated by Phillott, DC. London: Bernard Quaritch. 1908.

- "International Association for Falconry and Conservation of Birds of Prey – Role of IAF". Iaf.org. Archived from the original on 26 November 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "- intangible heritage – Culture Sector – UNESCO". Unesco.org. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "The Welsh Hawking Club", Austringer (36): 11, archived from the original on 2010-10-13, retrieved 2008-05-09.

- Evans, Humphrey (1973), Falconry, an illustrated introduction, John Bartholomew & Son, ISBN 0-85152-921-6.

- "Falconry, a living human heritage". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Sir Thomas Browne's Miscellany Tracts: Of Hawks and Falconry". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Katic, Stana (2009-10-08). Kimmel, James 'Jimmy' (ed.). "On Falconry". You tube (video). Archived from the original on 2012-09-23. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- aapone (6 May 2005). "My Mother Would Be a Falconress". My Mother Would Be a Falconress. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "haggard". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- "lure". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- "rouse". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- "pounce". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- "tail". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

Further reading

- Ash, Lydia, Modern Apprentice: site for North Americans interested in falconry. Much information for this entry was due to her research.

- Beebe, FL; Webster, HM (2000), North American Falconry and Hunting Hawks (8th ed.), ISBN 0-685-66290-X.

- Chenu, Jean Charles; Des Murs, Marc Athanase Parfait Œillet (1862). La fauconnerie, ancienne et moderne. Paris: Librairie L. Hachette et Cie.

- Chiorino, G. E. (1906). Il Manuale del moderno Falconiere. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli.

- Fernandes Ferreira (b. 1546), Diogo; Cordeiro (1844–1900), Luciano (1899). Arte da caça de altaneria. Lisbon: Lisboa Escriptorio.

- Freeman, Gage Earle; Salvin, Francis Henry (1859). Falconry : Its Claims, History and Practice. London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts.

- Freeman, Gage Earle (1869). Practical falconry – to which is added, How I became a falconer. London: Horace Cox.

- Fuertes, Louis Agassiz; Wetmore, Alexander (1920). "Falconry, the sport of kings". National Geographic Magazine. 38 (6).

- García, Beatriz E. Candil; Hartman, Arjen E (2007), Ars Accipitraria: An Essential Dictionary for the Practice of Falconry and hawking, London: Yarak, ISBN 978-0-9555607-0-5 (the excerpt on the language of falconry comes from this book).

- ——— (2008), The Red-tailed Hawk: The Great Unknown, London: Yarak, ISBN 978-0-9555607-4-3.

- Harting, James Edmund (1891). Bibliotheca Accipitraria: A Catalogue of Books Ancient and Modern Relating to Falconry, with notes, glossary and vocabulary. London: Bernard Quaritch.

- López de Ayala (1332–1407), Pedro; de la Cueva, duque de Albuquerque (d. 1492), Beltrán; de Gayangos (1809–1897), Pascual; Lafuente y Alcántara, Emilio (1869). El libro de las aves de caça. Madrid: M. Galiano.

- Latini (1220–1295), Brunetto; Bono (c. 1240 – c. 1292), Giamboni (1851). de Mortara, Alessandro (ed.). Scritture antiche toscane di falconeria ed alcuni capitoli nell' originale francese del Tesoro di Brunetto Latini sopra la stessa materia. Prato: Tipografia F. Alberghetti e C.

- Phillott, Douglas Craven; al-Dawlah Timur Mirza, Husam (1908). The Baz-nama-yi Nasiri, a Persian treatise on falconry. London: Bernard Quaritch.

- Riesenthal, Oskar von (1876). Die Raubvögel Deutschlands und des angrenzenden Mitteleuropas; Darstellung und Beschreibung der in Deutschland und den benachbarten Ländern von Mitteleuropa vorkommenden Raubvögel. Cassel, Germany: Verlag von Theodor Fischer.

- Deva, Raja of Kumaon, Rudra; Shastri (tr.), Hara Prasad (1910). Syanika satra: or a book on hawking. Calcutta: Asiatic Society.

- Soma, Takuya. 2012. ‘Contemporary Falconry in Altai-Kazakh in Western Mongolia’The International Journal of Intangible Heritage (vol.7), pp. 103–111. Archived 2017-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Soma, Takuya. 2013. 'Ethnographic Study of Altaic Kazakh Falconers', Falco: The Newsletter of the Middle East Falcon Research Group 41, pp. 10–14.