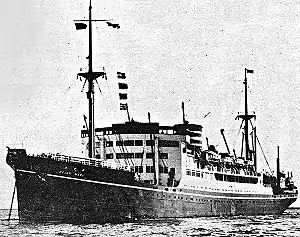

Heian Maru (1930)

Heian Maru (平安丸) was a Japanese ocean liner launched in 1930 and operated primarily on the NYK line's trans-Pacific service between Yokohama and Seattle. Shortly before the outbreak of the Pacific War, it was requisitioned by the Imperial Japanese Navy and converted to use as an auxiliary submarine tender. In 1944 it was sunk by American aircraft at Chuuk Lagoon during Operation Hailstorm. Its submerged hulk – the largest of Chuuk's "Ghost Fleet" – remains a popular scuba diving destination.

Heian Maru, ca. 1937 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Heian Maru |

| Builder | Ōsaka Iron Works, Japan |

| Laid down | 19 June 1929 |

| Launched | 16 April 1930 |

| Completed | 24 November 1930 |

| Stricken | 18 February 1944 |

| Fate | Sunk 1944 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 11,615 grt |

| Length | 163.3 m (535 ft 9 in) overall |

| Beam | 20.1 m (65 ft 11 in) |

| Draught | 12.5 m (41 ft 0 in) |

| Propulsion | 2×B&W-Ikegai diesels:*2 shafts:*13,404 bhp |

| Speed | 18.4 knots (21.2 mph; 34.1 km/h) |

| Capacity | 330 passengers (76 first class, 69 tourist class, 185 third class) |

| Crew | 130 |

| Armament | 4×15 cm/50 41st Year Type naval guns; *4×13 mm AA guns |

Background

In the late 1920s the Japanese shipping company Nippon Yūsen (NYK) began a major shipbuilding program, aimed at expanding its international passenger service. Of eight passenger liners built, three were of the Hikawa Maru class, designed mainly for service on NYK's Yokohama-Seattle route. The three ships were the Hikawa Maru, Hiye Maru, and Heian Maru.

Construction of the Heian Maru, planned as an 11,616-ton combined passenger-cargo liner, began 19 June 1929 at Ōsaka Iron Works. It was named in honor of Kyoto's historic Heian Shrine and launched on 24 November 1930. Fitting out was completed on 24 November, and on 18 December Heian Maru began her maiden ocean crossing, from Hong Kong to Seattle.[1]

Ocean liner

Heian Maru entered regular service, delivering passengers, cargo, and mail, her initial route being Hong Kong, Shanghai, Moji, Kobe, Yokohama, Victoria and Seattle, with occasional stops at Yokkaichi, Nagoya, and Shimizu.

From early 1935 she served the Osaka to Seattle route, with calls at Kobe, Nagoya, and Shimizu. The return trip was to Yokohama, Kobe and Osaka. From April 1935 most voyages started and finished at Kobe, with stops at Yokohama, Vancouver, and Seattle. Due to the speed of Heian Maru and her two sister ships, NYK was able to maintain regular departures from Seattle for Yokohama every three weeks.[2]

Heian Maru was a fast, modern, mid-sized liner capable of taking 300 passengers across the Pacific in comfort. Her interiors were done in Old English style, and when opened for tours in Seattle she attracted thousands of visitors. One 1934 American passenger described the galley's attempts at American-style food as poor, but was impressed by the vessel's compactness of design, clever engineering, and professional crew.[3]

On 30 March 1937 she brought Prince and Princess Chichibu to Vancouver on their Royal Visit on their way to the coronation of King George VI.[4][5]

On 26 July 1941, President Roosevelt ordered the freezing of all Japanese assets in the United States.[6] Heian Maru, en route to Seattle, was forced to spend two days sitting 150 miles off Cape Flattery while officials worked out a guarantee that the ship would not be seized once it entered American waters. Among the passengers, waiting anxiously, were numerous Jewish refugees from war-torn Europe, who had received transit visas from Chiune Sugihara, Japanese consul in Lithuania. Once in port the ship was refused permission to discharge its cargo of raw silk (valued at $1,000,000) bound for New Jersey mills. Only after five separate legal claims were initiated by the American customers of this cargo did the government relent and let it be offloaded.[7] All passengers disembarked in Seattle, including 69 bound for Vancouver, B.C.[8] Further diplomatic furor arose when, among 144 Japanese passengers preparing to board the ship for the return voyage to Yokohama, both men and women were stripped to their underwear and searched by American officials.[9] The ship sailed in ballast from Seattle for the last time on 4 August 1941.

Submarine tender

After Heian Maru returned to Japan in August 1941, NYK was informed that due to rising tension between Japan and the United States, the liner would be converted to military use. On 3 October the ship was formally requisitioned by the Imperial Japanese Navy, and designated an auxiliary submarine tender with the Yokosuka Naval District. Two weeks later conversion was begun at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Kobe. Amongst numerous other alterations, four 15 cm/50 41st Year Type naval guns, two dual-mount 13 mm AA guns, two searchlights, and a rangefinder were installed.[1]

The outbreak of World War II in the Pacific on 7 December 1941 (8 December in Japan) found Heian Maru still being refitted, but by the end of the month she was on her way to Kwajalein to take up a new posting with IJN 6th Fleet. In early February 1942, while at Kwajalein, Heian Maru's crew got their first experience in combat during raids launched from the American aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6).

Throughout 1942 and into the early months of 1943, the Heian Maru shuttled between Japanese bases at Truk (later known as Chuuk Atoll), Rabaul in the Solomon Islands, and Yokosuka and Kure, in Japan. She performed her designated task of supplying the dozen submarines of the IJN 6th Fleet with torpedoes, provisions, spare parts, and replacement crewmen, but, with her capacious holds, was also used as a troop and general cargo transport. At Rabaul in January 1943 Heian Maru was caught in two major Allied aerial attacks, during which she narrowly avoided bomb hits.[1]

On 2 June 1943 Heian Maru was reassigned to the IJN 5th Fleet and arrived at Paramushiro in the Kuril Islands to support operations in the Aleutian Islands. She was used as a floating command post for the secret successful withdrawal of 5,000 Japanese troops from the island of Kiska, then returned to Yokosuka on 14 August and was returned to the IJN 6th Fleet.

Over the next several months, Heian Maru was busy transporting troops, vehicles, and other supplies of the IJA 17th Infantry Division from Shanghai to Truk and Rabaul. During a brief refit at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, her four 152-mm guns were replaced by two Type 10 120-mm guns, two Type 96 anti-aircraft guns and a Type 2 sonar. She was repainted in a dazzle camouflage pattern. Afterwards, she ferried torpedoes, distilled water, and other cargo to Truk, and, on 19 November, had a tense encounter with the American submarine USS Dace (SS-247) which tested her new commander, Captain Tamaki Toshiharu. She spent December 1943 and January 1944 disbursing supplies to submarines and other ships of the Combined Fleet at Truk lagoon.

The Japanese naval base at Truk was a large, sprawling complex, with hundreds of vessels anchored among dozens of islands, surrounded by a protective coral reef. The islands were studded with airfields, hospitals, repair shops, storage sheds, fuel depots, and command facilities. It was defended by coastal guns in concrete casemates, hundreds of fighter planes, and hundreds of anti-aircraft guns of all types, both on ship and shore.[10] Heian Maru was moored next to her sister ship Hikawa Maru (in wartime service as a hospital ship) on the leeward side of Dublon Island when, on the morning of 17 February 1944, the Americans launched Operation Hailstone.

Carried out by the US Navy's Task Force 58, with nine aircraft carriers, under the command of Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, Hailstone was a massive two-day combined air-surface-submarine raid. Although the IJN had moved its aircraft carriers and battleships from Truk a short time earlier, their defenses were unprepared for the scale of the attack, and the remaining navy and merchant vessels were devastated by wave after wave of American warplanes. Heian Maru quickly put to sea and went into evasive maneuvers north of Dublon Island - with Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi and his Sixth Fleet staff on board - but as one of the largest targets in the lagoon, enemy attacks were relentless. At mid-morning two bombs fell close astern, damaging one of her propeller shafts and flooding an aft hold. The crew managed to correct the trim by pumping fuel to her bow tanks, and after sunset Heian Maru returned to Dublon, where Admiral Takagi and some of the ship's cargo of Type 95 torpedoes were offloaded.[1]

Early the following morning, 18 February 1944, Heian Maru got underway as the American aerial attacks resumed. Shortly after 0300 she was struck, in quick succession, by two pairs of bombs; fire engulfed the bridge and threatened the hold containing the remaining torpedoes. The wounded ship began sinking, and at about 0500 Captain Tamaki gave the order to abandon ship. Most of the crew, including Tamaki, reached the shore safely, but a total of 18 men were killed, and 25 wounded.[1]

At 0900, Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers from USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) attacked the still-burning Heian Maru, a torpedo striking her amidships on the port side. She sank soon after, coming to a rest on her port side in about 110 feet of water.

On 31 March 1944 the Heian Maru was officially removed from the navy list.[1]

Dive site

Chuuk Lagoon, in the Caroline Islands, now part of the Federated States of Micronesia, is a popular destination for recreational/sport divers around the world. In the 1960s, scuba divers began locating and identifying the hulks of Japanese ships sunk during Operation Hailstone (as well as later raids). The lagoon became well known after being the subject of a 1971 episode of The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, titled 'Lagoon of Lost Ships'. Of the roughly 45 ship wrecks that make up Chuuk's "Ghost Fleet", the Heian Maru is among the most popular with divers. Its depth of about 33 metres or 108 feet (12 metres or 39 feet on upper/starboard side),[11] in relatively clear, still waters, makes it accessible to moderately experienced scuba divers. It is the largest wreck in the lagoon (the somewhat larger Tonan Maru No.3 was refloated post-war),[11] and its name is still clearly visible on the bow, in both English and Japanese. Lying on its port side, some of the Heian Maru's cargo holds are accessible, revealing stockpiles of torpedoes, artillery shells, submarine periscopes, and numerous other items.

In recent years there has been growing concern by Chuukese and environmental groups over potential damage to the lagoon as the slowly corroding wrecks begin leaking heavy fuel oil.[12]

Heian Maru and other Japanese wrecks in Chuuk Lagoon are officially designated as war graves by the Japanese government.

References

- Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Tashirō Iwashige, The visual guide of Japanese wartime merchant marine, "Dainippon Kaiga". Archived from the original on 2002-12-07. (Japan), May 2009

- Ships of the World special issue, The Golden Age of Japanese Passenger Liners, "Kaijinsha"., (Japan), May 2004

- Voyage of a Century "Photo Collection of NYK Ships", "Nippon Yūsen"., (Japan), October 1985

- The Maru Special, Japanese Naval Vessels No.29, "Japanese submarine tenders w/ auxiliary submarine tenders", "Ushio Shobō". (Japan), July 1979

- The Maru Special, Japanese Naval Vessels No.53, "Japanese support vessels", Ushio Shobō (Japan), July 1981

Notes

- Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp and Peter Cundall. "IJN Submarine Tender Heian Maru". Combined Fleet website. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Transpacific Steam: The History of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast of North America to the Far East and the Antipodes, 1867-1941, E. Mowbray Tate

- Why Japan Was Strong: A Journey of Adventure, John Patric, 1943

- Yesaki, Mitsuo; Steves, Harold; Steves, Kathy (2005). Steveston Cannery Row: An Illustrated History. Mitsuo Yesaki. ISBN 9780968380710.

- "Home | Vancouver Sun".

- "United States freezes Japanese assets - Jul 26, 1941". History.com. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- Tate, E. Mobray (1986). Transpacific Steam: The Story of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast. Rosemount Publishing. p. 124. ISBN 0-8453-4792-6.

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle

- The "Magic" Background of Pearl Harbor, United States Department of Defense, Volume III (August 5, 1941-October 17, 1941)

- "War in the Pacific NHP: War in Paradise". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Michael McFadyen's Scuba Diving Web Site". Michaelmcfadyenscuba.info. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- "Chuuk Islands - The Blue and the Black - Foreign Correspondent". ABC.net.au. 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2016-02-18.