Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Hellenistic culture. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellenistic Judaism were Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria (now in southern Turkey), the two main Greek urban settlements of the Middle East and North Africa, both founded in the end of the fourth century BCE in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great. Hellenistic Judaism also existed in Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period, where there was a conflict between Hellenizers and traditionalists.

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

The major literary product of the contact between Second Temple Judaism and Hellenistic culture is the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible from Biblical Hebrew and Biblical Aramaic to Koine Greek, specifically, Jewish Koine Greek. Mentionable are also the philosophic and ethical treatises of Philo and the historiographical works of the other Hellenistic Jewish authors.[1][2]

The decline of Hellenistic Judaism started in the second century and its causes are still not fully understood. It may be that it was eventually marginalized by, partially absorbed into, or progressively became the Koine-speaking core of Early Christianity centered on Antioch and its traditions, such as the Melkite Greek Catholic Church and the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch.

Hellenism

The conquests of Alexander in the late fourth century BCE spread Greek culture and colonization—a process of cultural change called Hellenization—over non-Greek lands, including the Levant. This gave rise to the Hellenistic period, which sought to create a common or universal culture in the Alexandrian empire based on that of fifth-century Athens, along with a fusion of Near Eastern cultures.[3] The period is characterized by a new wave of Greek colonization which established Greek cities and kingdoms in Asia and Africa,[4] the most famous being Alexandria in Egypt. New cities established composed of colonists from different parts of the Greek world, and not from a specific metropolis ("mother city") as before.[4]

These Jews living in countries west of the Levant formed the Hellenistic diaspora. The Egyptian diaspora is the most well-known of these.[5] It witnessed close ties. Indeed, there was firm economic integration of Judea with the Ptolemaic Kingdom that ruled from Alexandria, while there were friendly relations between the royal court and the leaders of the Jewish community. This was a diaspora of choice, not of imposition. Information is less robust regarding diasporas in other territories. It suggests that the situation was by and large the same as it was in Egypt.[6]

Jewish life in both Judea and the diaspora was influenced by the culture and language of Hellenism. The Greeks viewed Jewish culture favorably, while Hellenism gained adherents among the Jews. While Hellenism has sometimes been presented (under the influence of 2 Maccabees, itself notably a work in Koine Greek) as a threat of assimilation diametrically opposed to Jewish tradition,

Adaptation to Hellenic culture did not require compromise of Jewish precepts or conscience. When a Greek gymnasium was introduced into Jerusalem, it was installed by a Jewish High Priest. And other priests soon engaged in wrestling matches in the palaestra. They plainly did not reckon such activities as undermining their priestly duties.

Later historians would sometimes depict Hellenism and Judaism uniquely incompatible, likely due to the influence of the persecution of Antiochus IV. However, it does not appear that most Jews in the Hellenistic era considered Greek rulers any worse or different from Persian or Babylonian ones. Writings of Hellenized Jews such as Philo of Alexandria show no particular belief that Judaism and Greek culture are incompatible; as another example, the Letter of Aristeas holds up Jews and Judaism in a favorable light by the standards of Greek culture. The one major difference that even the most Hellenized Jews did not appear to compromise on was the prohibition on polytheism; this still separated Hellenistic Jews from wider Greek culture in refusing to honor shrines, temples, gods, and so on other than their own God of Israel.[8]

Hellenistic rulers of Judea

Under the suzerainty of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and later the Seleucid Empire, Judea witnessed a period of peace and protection of its institutions.[9] For their aid against his Ptolemaic enemies, Antiochus III the Great promised his Jewish subjects a reduction in taxes and funds to repair the city of Jerusalem and the Second Temple.[9]

Relations deteriorated under Antiochus's successor Seleucus IV Philopator, and then, for reasons not fully understood, his successor Antiochus IV Epiphanes drastically overturned the previous policy of respect and protection, banning key Jewish religious rites and traditions in Judea (although not among the diaspora) and sparking a traditionalist revolt against Greek rule.[9] One of the possible reasons is that while Alexander the Great saw in Yahweh the «Jewish Zeus», Antiochus saw in him Seth-Typhon, that is, the «Anti-Zeus».[10] Out of this revolt was formed an independent Jewish kingdom known as the Hasmonean kingdom, which lasted from 141 BCE to 63 BCE. The Hasmonean Dynasty eventually disintegrated due to a civil war.

Hasmonean civil war

The Hasmonean civil war began when the High Priest Hyrcanus II (a supporter of the Pharisees) was overthrown by his younger brother, Aristobulus II (a supporter of the Sadducees). A third faction, consisting primarily of Idumeans from Maresha, led by Antipater and his son Herod, re-installed Hyrcanus, who, according to Josephus, was merely Antipater's puppet. In 47 BCE, Antigonus, a nephew of Hyrcanus II and son of Aristobulus II, asked Julius Caesar for permission to overthrow Antipater. Caesar ignored him, and in 42 BCE Antigonus, with the aid of the Parthians, defeated Herod. Antigonus ruled for only three years, until Herod, with the aid of Rome, overthrew him and had him executed. Antigonus was the last Hasmonean ruler.

Influence

The major literary product of the contact of Judaism and Hellenistic culture is the Septuagint, as well as the Book of Wisdom, Sirach, apocrypha and pseudepigraphic apocalyptic literature (such as the Assumption of Moses, the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Book of Baruch, the Greek Apocalypse of Baruch, etc.) dating to the period. Important sources are Philo of Alexandria and Flavius Josephus. Some scholars[11] consider Paul the Apostle to be a Hellenist as well, even though he himself claimed to be a Pharisee (Acts 23:6).

Philo of Alexandria was an important apologist of Judaism, presenting it as a tradition of venerable antiquity that, far from being a barbarian cult of an oriental nomadic tribe, with its doctrine of monotheism had anticipated tenets of Hellenistic philosophy. Philo could draw on Jewish tradition to use customs which Greeks thought as primitive or exotic as the basis for metaphors: such as "circumcision of the heart" in the pursuit of virtue.[12] Consequently, Hellenistic Judaism emphasized monotheistic doctrine (heis theos), and represented reason (logos) and wisdom (sophia) as emanations from God.

Beyond Tarsus, Alexandretta, Antioch, and Northwestern Syria (the main "Cilician and Asiatic" centers of Hellenistic Judaism in the Levant), the second half of the Second Temple period witnessed an acceleration of Hellenization in Israel itself, with Jewish high priests and aristocrats alike adopting Greek names:

'Ḥoni' became 'Menelaus'; 'Joshua' became 'Jason' or 'Jesus' [Ἰησοῦς]. The Hellenic influence pervaded everything, and even in the very strongholds of Judaism it modified the organization of the state, the laws, and public affairs, art, science, and industry, affecting even the ordinary things of life and the common associations of the people […] The inscription forbidding strangers to advance beyond a certain point in the Temple was in Greek; and was probably made necessary by the presence of numerous Jews from Greek-speaking countries at the time of the festivals (comp. the "murmuring of the Grecians against the Hebrews," Acts vi. 1). The coffers in the Temple which contained the shekel contributions were marked with Greek letters (Sheḳ. iii. 2). It is therefore no wonder that there were synagogues of the Libertines, Cyrenians, Alexandrians, Cilicians, and Asiatics in the Holy City itself (Acts vi. 9).[13]

"There is neither Jew nor Greek"

Ethnic, cultural, philosophical, and social tensions within the Hellenistic Jewish world were partly overcome by the emergence of a new, typically Antiochian, Middle-Eastern Greek doctrine (doxa), either by

- established, native Hellenized Cilician-Western Syrian Jews (themselves descendants of Babylonian Jewish migrants who had long adopted various elements of Greek culture and civilization while retaining a generally conservative, strict attachment to Halakha),

- heathen, 'Classical' Greeks, Macedonians, Greco-Syrian gentiles, or

- the local, native descendants of Greek or Greco-Syrian converts to mainstream Judaism – known as proselytes (Greek: προσήλυτος/proselytes) and Greek-speaking Jews born of mixed marriages.

Their efforts were probably facilitated by the arrival of a fourth wave of Greek-speaking newcomers to Cilicia and Northwestern Syria: Cypriot Jews and 'Cyrenian' (Libyan) Jewish migrants of non-Egyptian North African Jewish origin, as well as gentile Roman settlers from Italy—many of whom already spoke fluent Koine Greek and/or sent their children to Greek schools. Some scholars believe that, at the time, these Cypriot and Cyrenian North African Jewish migrants, such as Simon of Cyrene, were generally less affluent than the native Cilician-Syrian Jews and practiced a more 'liberal' form of Judaism, more propitious for the formation of a new canon:

[North African] Cyrenian Jews were of sufficient importance in those days to have their name associated with a synagogue at Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). And when the persecution arose about Stephen [a Hellenized Syrian-Cilician Jew], some of these Jews of Cyrene who had been converted at Jerusalem, were scattered abroad and came with others to Antioch and [initially] preached the word "unto the Jews only" (Acts 11:19, 20 the King James Version), and one of them, Lucius, became a prophet in the early church there [the nascent Greek 'Orthodox' community of Antioch].

— International Standard Bible Encyclopedia[14]

Decline of the Hellenistai and partial conversion to Christianity

The reasons for the decline of Hellenistic Judaism are obscure. It may be that it was marginalized by, absorbed into, or became Early Christianity (see the Gospel of the Hebrews). The Pauline epistles and the Acts of the Apostles report that, after his initial focus on the conversion of Hellenized Jews across Anatolia, Macedonia, Thrace and Northern Syria without criticizing their laws and traditions,[15][16] Paul the Apostle eventually preferred to evangelize communities of Greek and Macedonian proselytes and Godfearers, or Greek circles sympathetic to Judaism: the Apostolic Decree allowing converts to forego circumcision made Christianity a more attractive option for interested pagans than Rabbinic Judaism, which required ritual circumcision for converts (see Brit milah). See also Circumcision controversy in early Christianity[17][18] and the Abrogation of Old Covenant laws.

The attractiveness of Christianity may, however, have suffered a setback with its being explicitly outlawed in the 80s CE by Domitian as a "Jewish superstition", while Judaism retained its privileges as long as members paid the fiscus Judaicus.

The opening verse of Acts 6 points to the problematic cultural divisions between Hellenized Jews and Aramaic-speaking Israelites in Jerusalem, a disunion that reverberated within the emerging Christian community itself:

it speaks of "Hellenists" and "Hebrews." The existence of these two distinct groups characterizes the earliest Christian community in Jerusalem. The Hebrews were Jewish Christians who spoke almost exclusively Aramaic, and the Hellenists were also Jewish Christians whose mother tongue was Greek. They were Greek-speaking Jews of the Diaspora, who returned to settle in Jerusalem. To identify them, Luke uses the term Hellenistai. When he had in mind Greeks, gentiles, non-Jews who spoke Greek and lived according to the Greek fashion, then he used the word Hellenes (Acts 21.28). As the very context of Acts 6 makes clear, the Hellenistai are not Hellenes.[19]

Some historians believe that a sizeable proportion of the Hellenized Jewish communities of Southern Turkey (Antioch, Alexandretta and neighboring cities) and Syria/Lebanon converted progressively to the Greco-Roman branch of Christianity that eventually constituted the "Melkite" (or "Imperial") Hellenistic churches of the MENA area:

As Christian Judaism originated at Jerusalem, so Gentile Christianity started at Antioch, then the leading center of the Hellenistic East, with Peter and Paul as its apostles. From Antioch it spread to the various cities and provinces of Syria, among the Hellenistic Syrians as well as among the Hellenistic Jews who, as a result of the great rebellions against the Romans in A.D. 70 and 130, were driven out from Jerusalem and Palestine into Syria.[20]

Cultural legacy

Widespread influence beyond Second Temple Judaism

Both Early Christianity and Early Rabbinical Judaism were far less 'orthodox' and less theologically homogeneous than they are today; and both were significantly influenced by Hellenistic religion and borrowed allegories and concepts from Classical Hellenistic philosophy and the works of Greek-speaking Jewish authors of the end of the Second Temple period before the two schools of thought eventually affirmed their respective 'norms' and doctrines, notably by diverging increasingly on key issues such as the status of 'purity laws', the validity of Judeo-Christian messianic beliefs, and, more importantly, the use of Koiné Greek and Latin as liturgical languages replacing Biblical Hebrew, etc.[21]

First synagogues in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East

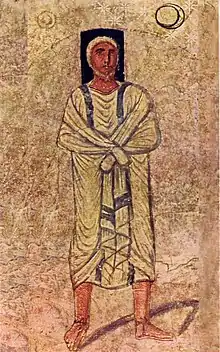

The word synagogue itself comes from Jewish Koiné Greek, a language spoken by Hellenized Jews across Southeastern Europe (Macedonia, Thrace, Northern Greece), North Africa and the Middle East after the 3rd century BCE. Many synagogues were built by the Hellenistai or adherents of Hellenistic Judaism in the Greek Isles, Cilicia, Northwestern and Eastern Syria and Northern Israel as early as the first century BCE- notably in Delos, Antioch, Alexandretta, Galilee and Dura-Europos: because of the mosaics and frescos representing heroic figures and Biblical characters (viewed as potentially conductive of "image worship" by later generations of Jewish scholars and rabbis), many of these early synagogues were at first mistaken for Greek temples or Antiochian Greek Orthodox churches.

Mishnaic and Talmudic concepts

Many of the Jewish sages who compiled the Mishnah and earliest versions of the Talmud were Hellenized Jews, including Johanan ben Zakai, the first Jewish sage attributed the title of rabbi and Rabbi Meir, the son of proselyte Anatolian Greek converts to Early Rabbinical Judaism.

Even Israeli rabbis of Babylonian Jewish descent such as Hillel the Elder whose parents were Aramaic-speaking Jewish migrants from Babylonia (hence the nickname "Ha-Bavli"), had to learn Greek language and Greek philosophy in order to be conversant with sophisticated rabbinical language – many of the theological innovations introduced by Hillel had Greek names, most famously the Talmudic notion of Prozbul, from Koine Greek προσβολή, "to deliver":

Unlike literary Hebrew, popular Aramaic or Hebrew constantly adopted new Greek loanwords, as is shown by the language of the Mishnaic and Talmudic literature. While it reflects the situation at a later period, its origins go back well before the Christian era. The collection of the loanwords in the Mishna to be found in Schürer shows the areas in which Hellenistic influence first became visible- military matters, state administration and legislature, trade and commerce, clothing and household utensils, and not least in building. The so-called copper scroll with its utopian list of treasures also contains a series of Greek loanwords. When towards the end of the first century BCE, Hillel in practice repealed the regulation of the remission of debts in the sabbath year (Deut. 15.1-11) by the possibility of a special reservation on the part of the creditor, this reservation was given a Greek name introduced into Palestinian legal language- perōzebbōl = προσβολή, a sign that even at that time legal language was shot through with Greek.

— Martin Hengel, Judaism and Hellenism (1974)

Influence on Levantine Byzantine traditions

The unique combination of ethnocultural traits inhered from the fusion of a Greek-Macedonian cultural base, Hellenistic Judaism and Roman civilization gave birth to the distinctly Antiochian “Middle Eastern-Roman” Christian traditions of Cilicia (Southeastern Turkey) and Syria/Lebanon:

"The mixture of Roman, Greek, and Jewish elements admirably adapted Antioch for the great part it played in the early history of Christianity. The city was the cradle of the church".[22]

Some typically Grecian "Ancient Synagogal" priestly rites and hymns have survived partially to the present, notably in the distinct church services of the followers of the Melkite Greek Catholic church and its sister-church the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch in the Hatay Province of Southern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Northern Israel, and in the Greek-Levantine Christian diasporas of Brazil, Mexico, the United States and Canada.

But many of the surviving liturgical traditions of these communities rooted in Hellenistic Judaism and, more generally, Second Temple Greco-Jewish Septuagint culture, were expunged progressively in the late medieval and modern eras by both Phanariot European-Greek (Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople) and Vatican (Roman Catholic) gentile theologians who sought to 'bring back' Levantine Greek Orthodox and Greek-Catholic communities into the European Christian fold: some ancient Judeo-Greek traditions were thus deliberately abolished or reduced in the process.

Members of these communities still call themselves "Rûm" (literally "Roman"; usually referred to as "Byzantine" in English) and referring to Greeks in Turkish, Persian and Levantine Arabic. In that context, the term Rûm is preferred over Yāvāni or Ionani (literally "Ionian"), also referring to Greeks in Ancient Hebrew, Sanskrit and Classical Arabic.

Individual Hellenized Jews

Hellenistic and Hasmonean Period

- Andronicus son of Meshullam, Egyptian Jewish scholar of the 2nd century BCE. One of the first known advocates of early Pharisaic (proto-Rabbinical) orthodoxy against the Samaritans.

- Antigonus of Sokho, also known as Antigonos of Socho, was the first scholar of whom Pharisaic tradition has preserved not only the name but also an important theological doctrine. He flourished about the first half of the third century BCE. According to the Mishnah, he was the disciple and successor of Simon the Just. Antigonus is also the first noted Jew to have a Greek name, a fact commonly discussed by scholars regarding the extent of Hellenic influence on Judaism following the conquest of Judaea by Alexander the Great.

- Antigonus II Mattathias (known in Hebrew as Matityahu) was the last Hasmonean king of Judea. Antigonus was executed in 37 BCE, after a reign of three years during which he led the national struggle of the Jews for independence from the Romans.

- Alexander of Judaea, or Alexander Maccabeus, was the eldest son of Aristobulus II, king of Judaea[23]

- Aristobulus of Alexandria (fl. 181–124 BCE), philosopher of the Peripatetic school who attempted to fuse ideas in the Hebrew Scriptures with those in Greek thought

- Jason of the Oniad family, High Priest in the Temple in Jerusalem from 175 to 172 BCE

- Menelaus, High Priest in Jerusalem from 171 BCE to about 161 BCE

- Mariamne I, Jewish princess of the Hasmonean dynasty, was the second wife of Herod the Great.

- Onias I (Hellenized form of Hebrew name (Greek: Ὀνίας) from (Hebrew: Honiyya) was the son of Jaddua mentioned in Nehemiah.[24] According to Josephus, this Jaddua is said to have been a contemporary of Alexander the Great.[25] I Maccabees regards Onias as a contemporary of the Spartan king Areus I (309-265 BCE).[26] Onias I is thought to be the father or grandfather of Simon the Just.

- Ben Sira, also known as Yesu'a son of Sirach, leading 2nd century BCE Jewish scholar and theologian who lived in Jerusalem and Alexandria, author of the Wisdom of Sirach, or "Book of Ecclesiasticus".

- Simeon the Just or Simeon the Righteous (Hebrew: שמעון הצדיק Shimon HaTzaddik) was a Jewish High Priest during the time of the Second Temple.

- Simon Thassi (died 135 BCE) was the second son of king Mattathias and the first prince of the Jewish Hasmonean Dynasty. He was also a general (Doric Greek: στραταγός, stratagos; literally meaning "army leader") in the Greco-Syrian Seleucid army of Antiochus VI

Herodian and Roman Period

- Philo of Alexandria (Greek: Φίλων, Philōn; c. 20 BCE – c. 50 CE), also called Philo Judaeus, of Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt

- Titus Flavius Josephus, was the first Jewish historian. Initially a Jewish military leader during the First Jewish-Roman War, he famously switched sides and became a Roman citizen and acclaimed Romano-Jewish academic. He popularized the idea that Judaism was similar in many ways to Greek philosophy

- Justus of Tiberias, Jewish historian born in Tiberias, "a highly Hellenistic Galilean city", he was a secretary to governor Herod Agrippa II and rival of Titus Flavius Josephus

- Julianos (Hellenized form of the Latin name Julianus) and Pappos (from Koine Greek pappa or papas 'patriarch' or 'elder') born circa 80 CE in the city of Lod (Hebrew: לוֹד; Greco-Latin: Lydda, Diospolis, Ancient Greek: Λύδδα / Διόσπολις – city of Zeus), one of the main centers of Hellenistic culture in central Israel. Julianos and Pappos led the Jewish resistance movement against the Roman army in Israel during the Kitos War, 115-117 CE (their Hebrew names were Shamayah and Ahiyah respectively)

- Lukuas, also called Andreas, Libyan Jew born circa 70 CE, was one of the main leaders the Jewish resistance movement against the Roman army in North Africa and Egypt during the Kitos War, 115-117 CE

- Rabbi Meir, a famous Jewish sage who lived in Galilee in the time of the Mishna, is thought to be the son of Anatolian Greek (Talmud, Tractate Kilayim) gentile proselyte converts to Pharisaic Judaism (folk etymologies and mistranslations connected him, wrongly, to the family of Emperor Nero). He was the son-in-law of Haninah ben Teradion, himself a Hellenized Jewish aristocrat and leading rabbinical figure in late 1st century CE Jewish theology.

- Rabbi Tarfon (Hebrew: רבי טרפון, from the Greek name Τρύφων Tryphon), a kohen,[27] was a member of the third generation of the Mishnah sages, who lived in the period between the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE) and the fall of Betar (135 CE). Thought to be originally from the region of Lod (Hebrew: לוֹד; Greco-Latin: Lydda, Diospolis, Ancient Greek: Λύδδα / Διόσπολις – city of Zeus), one of the main centers of Hellenistic culture in central Israel, R. Tarfon was one of the most vociferous Jewish critics of Early Christianity

- Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion, prominent Galilean Jewish scholar and teacher. His father's name (Teradion) is thought to be of Judeo-Greek origin. Also, 'Hananiah' (or 'Haninah') was a popular name amongst the Hellenized Jews of Syria and Northern Israel (pronounced 'Ananias' in Greek). He was a leading figure in late 1st century CE Jewish theology and one of the Ten Martyrs murdered by the Romans for ignoring the ban on teaching Torah

- Trypho the Jew, thought to be a 2nd-century CE rabbi opposed to Christian apologist Justin Martyr, whose Dialogue with Trypho is paradoxically "equally influenced by Greek and Rabbinic thought."[28] He is most likely the same as Rabbi Tarfon.

Late Antiquity and Early Medieval Era

- Rav Pappa (Hebrew: רב פפא, from Koine Greek pappa or papas 'patriarch' or 'elder' – originally 'father') (ca. 300 – died 375) was a Jewish Talmudist who lived in Babylonia, at a time when Judeo-Aramaic culture was regaining the upper hand against classical Hellenistic Judaism, notably amongst Jewish communities in Babylonia which reverted progressively to the pre-Hellenistic Aramaic culture

- Kalonymos family (Kαλώνυμος in Greek), first known rabbinical dynasty of Northern Italy and Central Europe: notable members include Ithiel I, author of Jewish prayer books (born circa 780 CE) and Kalonymus Ben Meshullam born in France circa 1000, spiritual leader of the Jewish community of Mainz in Western Germany

- The Radhanites: an influential group of Jewish merchants and financiers active in France, Germany, Central Europe, Central Asia and China in the Early Middle Ages – thought to have revolutionized the world economy and contributed to the creation of the 'Medieval Silk Road' long before Italian and Byzantine merchants. Cecil Roth and Claude Cahen, among others, claim their name may have come originally from the Rhône River valley in France, which is Rhodanus in Latin and Rhodanos (Ῥοδανός) in Greek, as the center of Radhanite activity was probably in France where their trade routes began.

See also

- Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch

- Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem

- History of Judaism

- Greek Jews

- History of the Jews in the Roman Empire

- Jerusalem during the Second Temple Period

- Jewish apocrypha

- Jewish Christianity

- List of events in early Christianity

- Origins of Christianity

- Paul the Apostle and Judaism

- Romaniote Jews

References

- Walter, N. Jüdisch-hellenistische Literatur vor Philon von Alexandrien (unter Ausschluss der Historiker), ANRW II: 20.1.67-120

- Barr, James (1989). "Chapter 3 - Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek in the Hellenistic age". In Davies, W.D.; Finkelstein, Louis (eds.). The Cambridge history of Judaism. Volume 2: The Hellenistic Age (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–114. ISBN 9781139055123.

- Roy M. MacLeod, The Library Of Alexandria: Centre Of Learning In The Ancient World

- Ulrich Wilcken, Griechische Geschichte im Rahmen der Alterumsgeschichte.

- "Syracuse University. "The Jewish Diaspora in the Hellenistic Period"". Archived from the original on 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- Hegermann, Harald (1990). "Chapter 4: The Diaspora in the Hellenistic age". In Davies, W.D.; Finkelstein, Louis (eds.). The Cambridge history of Judaism (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–166. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521219297.005. ISBN 9781139055123.

- Gruen, Erich S. (1997). "Fact and Fiction: Jewish Legends in a Hellenistic Context". Hellenistic Constructs: Essays in Culture, History, and Historiography. University of California Press. pp. 72 ff.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2008). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: The Coming of the Greeks: The Early Hellenistic Period (335–175 BCE). Library of Second Temple Studies. Vol. 68. T&T Clark. pp. 155–165. ISBN 978-0-567-03396-3.

- Gruen, Erich S. (1993). "Hellenism and Persecution: Antiochus IV and the Jews". In Green, Peter (ed.). Hellenistic History and Culture. University of California Press. pp. 238 ff.

- te Velde 1967, pp. 13–15.

- "Saul of Tarsus: Not a Hebrew Scholar; a Hellenist" Archived 2009-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Encyclopedia

- E. g., Leviticus 26:41, Ezekiel 44:7

- "Hellenism" Archived 2009-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, Jewish Encyclopedia, Quote: from 'Range of Hellenic Influence' and 'Reaction Against Hellenic Influence' sections

- Kyle, M. G. "Cyrene". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. via "Topical Bible: Cyrene". Bible Hub. Archived from the original on 2015-05-09. Retrieved 2015-02-21.

- Acts 16:1–3

- McGarvey on Acts 16 Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine: "Yet we see him in the case before us, circumcising Timothy with his own hand, and this 'on account of certain Jews who were in those quarters. '"

- 1 Corinthians 7:18

- "making themselves foreskins"; I Macc. i. 15; Josephus, "Ant." xii. 5, § 1; Assumptio Mosis, viii.; I Cor. vii. 18;, Tosef.; Talmud tractes Shabbat xv. 9; Yevamot 72a, b; Yerushalmi Peah i. 16b; Yevamot viii. 9a; Archived 2020-05-08 at the Wayback Machine; Catholic Encyclopedia: Circumcision Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine: "To this epispastic operation performed on the athletes to conceal the marks of circumcision St. Paul alludes, me epispastho (1 Corinthians 7:18)."

- " Conflict and Diversity in the Earliest Christian Community" Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, Fr. V. Kesich, O.C.A.

- "History of Christianity in Syria" Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine, Catholic Encyclopedia

- Daniel Boyarin. "Dying for God: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity and Judaism", Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999, p. 15.

- "Antioch," Encyclopaedia Biblica, Vol. I, p. 186 (p. 125 of 612 in online .pdf file.

- Alexander II of Judea Archived 2011-10-16 at the Wayback Machine at the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Nehemiah xii. 11

- Jewish Antiquities xi. 8, § 7

- I Macc. xii. 7, 8, 20

- Talmud Bavli, Kiddushin, 71a

- Philippe Bobichon (ed.), Justin Martyr, Dialogue avec Tryphon, édition critique, introduction, texte grec, traduction, commentaires, appendices, indices, (Coll. Paradosis nos. 47, vol. I-II.) Editions Universitaires de Fribourg Suisse, (1125 pp.), 2003

Further reading

| Library resources about Hellenistic Judaism |

Foreign language

- hrsg. von W.G. Kümmel und H. Lichtenberger (1973), Jüdische Schriften aus hellenistisch römischer Zeit (in German), Gütersloh

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Delling, Gerhard (1987), Die Begegnung zwischen Hellenismus und Judentum Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt (in German), vol. Bd. II 20.1

English

- Borgen, Peder. Early Christianity and Hellenistic Judaism. Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark, 1996.

- Cohen, Getzel M. The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa. Hellenistic Culture and Society 46. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Gruen, Erich S. Constructs of Identity In Hellenistic Judaism: Essays On Early Jewish Literature and History. Boston: De Gruyter, 2016.

- Mirguet, Françoise. An Early History of Compassion: Emotion and Imagination In Hellenistic Judaism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Neusner, Jacob, and William Scott Green, eds. Dictionary of Judaism in the Biblical Period: 450 BCE to 600 CE. 2 vols. New York: Macmillan Library Reference, 1996.

- Tcherikover, Victor (1975), Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews, New York: Atheneum

- The Jewish Encyclopedia

- te Velde, Herman (1967). Seth, God of Confusion: a study of his role in Egyptian mythology and religion. Probleme der Ägyptologie. Vol. 6. Translated by van Baaren-Pape, G.E. (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05402-8.