Krymchaks

The Krymchaks (Krymchak: plural: кърымчахлар, qrımçahlar, singular: кърымчах, qrımçah) are Jewish ethno-religious communities of Crimea derived from Turkic-speaking adherents of Rabbinic Judaism.[3] They have historically lived in close proximity to the Crimean Karaites, who follow Karaite Judaism.

Krymchak community in Ukraine. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,200–1,500 (est)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,200[2] | |

| 406 (2001)[3] | |

| 954 (2021)[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Krymchak | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Crimean Tatars, other Jews, especially Crimean Karaites | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

At first krymchak was a Russian descriptive used to differentiate them from their Ashkenazi Jewish coreligionists, as well as other Jewish communities in the former Russian Empire such as the Georgian Jews, but in the second half of the 19th century this name was adopted by the Krymchaks themselves. Before this their self-designation was "Срель балалары" (Srel balalary) – literally "Children of Israel". The Crimean Tatars referred to them as zuluflı çufutlar ("Jews with pe'ot") to distinguish them from the Karaites, who were called zulufsız çufutlar ("Jews without pe'ot").

Language

The Krymchaks speak a modified form of the Crimean Tatar language, called the Krymchak language. It is the Jewish patois,[5] or ethnolect of Crimean Tatar, which is a Kypchak Turkic language. Before the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Krymchaks were at least bilingual: they spoke the Krymchak ethnolect and at the same time mostly used Hebrew for their religious life and for written communication. The Krymchaks adhered to their Turkic patois up to World War II, but later began to lose their linguistic identity. Now they are making efforts to revive their language. Many of the linguistic characteristics of the Krymchak language could be found in the Crimean Tatar language. In addition, it contains numerous Hebrew and Aramaic loan-words and was traditionally written in Hebrew characters (now it is written in Cyrillic script).

Origins

The Krymchaks are likely a result of diverse origins whose ancestors probably included Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews, and Jews from the Byzantine empire, Genoa, Georgia, and other places.[6]

Other more speculative theories include that the Krymchaks are probably partially descended from Jewish refugees who settled along the Black Sea in ancient times. Jewish communities existed in many of the Greek colonies in the region during the late classic period. Recently excavated inscriptions in Crimea have revealed a Jewish presence at least as early as the 1st century BCE. In some Crimean towns, monotheistic pagan cults called sebomenoi theon hypsiston ("Worshippers of the All-Highest God," or "God-Fearers") existed. These quasi-proselytes kept the Jewish commandments but remained uncircumcised and retained certain pagan customs. Eventually, these sects disappeared as their members adopted either Christianity or normative Judaism. Another theory is that after the suppression of Bar Kokhba's revolt by the emperor Hadrian, those Jews who were not executed were exiled to the Crimean peninsula.

The late classical era saw great upheaval in the region as Crimea was occupied by Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Khazars, and other peoples. Jewish merchants such as the Radhanites began to develop extensive contacts in the Pontic region during this period, and probably maintained close relations with the proto-Krymchak communities. Khazar dominance of Crimea during the Early Middle Ages is considered to have had at least a partial impact on Krymchak demographics.

Middle Ages

In the late 7th century most of Crimea fell to the Khazars. In the 12th century, Rabbi Yehuda haLevi wrote a philosophical work known as the Kuzari, in which he placed a learned Jew in a long discussion with the Khazar king, who was searching for the religion he would take up. A belief arose that his people followed him into Judaism. In the 20th century, a Jewish writer by the name of Arthur Koestler suggested that Ashkenazi Jews descended from this episode. Since then, this theory has reemerged, including by antisemites who seek to deny continuity between ancient Jews with modern Jewish populations.

In 2013, Professor Shaul Stampfer of the history department of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, argued that Kuzari was never intended to be a true description of the events but merely an allegory using the supposed discussion to explain Jewish philosophy. According to Stampfer, there are no Jewish graveyards, buildings, writings or references in the writings of others to suggest that there was ever any significant Jewish community among the Khazars or their leadership.[7]

During the period of Khazar rule, some degree of intermarriage between Crimean Jews and Khazars could have occurred, but suggestions that the Krymchaks absorbed numerous Khazar refugees during the decline and fall of the Khazar kingdom (or during the Khazar successor state, ruled by Georgius Tzul, centered in Kerch), seem to be fanciful. It is known that Kipchak converts to Judaism existed, and it is possible that from these converts the Krymchaks adopted their distinctive language.

In times when the Crimea belonged to the Byzantine Empire and after then, waves of Byzantine Jews settled there. These newcomers were in most cases merchants from Constantinople and brought with them Romaniote Jewish practices (Bonfil 2011).

The Mongol conquerors of the Pontic–Caspian steppe were promoters of religious freedom, and the Genoese occupation of southern Crimea (1315–1475) saw rising degrees of Jewish settlement in the region. The Jewish community was divided among those who prayed according to the Sephardi, Ashkenazi and Romaniote rites. In 1515 the different traditions were united into a distinctive Krymchak prayer book, which represented the Romaniote rite[8][9] by Rabbi Moshe Ha-Golah, a Chief Rabbi of Kiev, who had settled in Crimea.[10]

In the 18th century the community was headed by David Ben Eliezer Lehno (d. 1735), author of the introduction to the "Kaffa" rite prayer book and Mishkan David ("Abode of David"), devoted to Hebrew grammar. He was also the author of a monumental Hebrew historical chronicle, Devar sefataim ("Utterance the mouth"), on the history of the Crimean Khanate.

Tatar rule

Under the Crimean Khanate the Jews lived in separate quarters and paid the dhimmi-tax (the Jizya). A limited judicial autonomy was granted according to the Ottoman millet system. Overt, violent persecution was extremely rare.

According to anthropologist S.Vaysenberg, "The origin of Krymchaks is lost in the darkness of the ages. Only one thing can be said, that they carry less Turkic blood than the Karaites, although certain kinship between both peoples and the Khazars can hardly be denied. But Krymchaks during the Middle Ages and modern times constantly mixed with their European counterparts. There was an admixture with Italian Jews from the time of the Genoeses with the arrival of the Lombroso, Pyastro and other families. Cases of intermarriage with Russian Jews occurred in recent times.

There is no general work on the ethnography of Krymchaks. The available summary of folklore materials is not complete. Extensive anthroponimic data has been collected from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but does not cover earlier periods, for which archival material does exist. The study of each of these groups of sources can shed light on the ethnogenesis of the Krymchak ethnic minority.

Russian and Soviet rule

The Russian Empire annexed Crimea in 1783. The Krymchaks were thereafter subjected to the same religious persecution imposed on other Jews in Russia. Unlike their Karaite neighbors, the Krymchaks suffered the full brunt of anti-Jewish restrictions.

During the 19th century many Ashkenazim from Ukraine and Lithuania began to settle in Crimea. Compared with these Ashkenazim the Krymchaks seemed somewhat backward; their illiteracy rates, for example, were quite high, and they held fast to many superstitions. Intermarriage with the Ashkenazim reduced the numbers of the distinct Krymchak community dramatically. By 1900 there were 60,000 Ashkenazim and only 6,000 Krymchaks in Crimea.

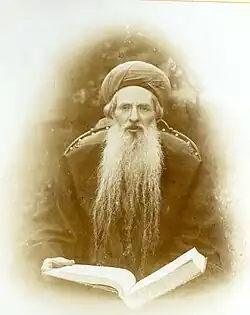

In the mid-19th century the Krymchaks became followers of Rabbi Chaim Hezekiah Medini, also known by the name of his work the Sedei Chemed, a Sephardi rabbi born in Jerusalem who had come to Crimea from Istanbul. His followers accorded him the title of gaon. Settling in Karasubazaar, the largest Krymchak community in Crimea, Rabbi Medini spent his life raising their educational standards.

By 1897, the Krymchaks stopped being "the majority of Talmudic Jews on the Crimean Peninsula".[11]

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, civil war tore apart Crimea. Many Krymchaks were killed in the fighting between the Red Army and the White Movement. More still died in the famines of the early 1920s and the early 1930s. Many emigrated to the Holy Land, the United States and Turkey.

Under Joseph Stalin, the Krymchaks were forbidden to write in Hebrew and were ordered to employ the Cyrillic alphabet to write their own language. Synagogues and yeshivas were closed by government decree. Krymchaks were compelled to work in factories and collective farms.

Holocaust and after

Unlike the Crimean Karaites, the Krymchaks were targeted for annihilation by the Nazis following the Axis capture of Crimea in 1941. Six thousand Krymchaks, almost 75% of their population, were killed during the Holocaust. Moreover, upon the return of Soviet authority to the region in 1944, many Krymchaks found themselves forcibly deported to Central Asia along with their Crimean Tatar neighbors.[12]

By 2000, only about 600 Krymchaks lived in the former Soviet Union, about half in Ukraine and the remainder in Georgia, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Some 600–700 Krymchaks still clinging to their Crimean identity live in Israel,[2] and others in the United States and Canada.

Culture

The Krymchaks practice Orthodox or Talmudic Judaism. Their unique nusah, or prayer book, known as Nusah Kaffa, emerged during the 16th century. Kaffa was a former name of the Crimean city of Feodosia.[6]

Traditional occupations for the Krymchaks included farming, trade, and viticulture.[6]

The dress and customs of the Krymchaks resembled that of the nearby Karaites and Crimean Tatars. [6]

The Krymchaks considered themselves a distinct group and rarely intermarried with Karaites or the Crimean Tatars. The Krymchaks used to practice polygamy but then adopted monogamy by the late 19th century.[6]

See also

References

- Kizilov, M. Krymchaks: Modern situation of the community. "Eurasian Jewish Annual". 2008

- "Михаил Кизилов. Крымчаки: современное состояние общины". Archived from the original on 2015-10-17. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- Krymchaks Archived 2014-06-22 at the Wayback Machine at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- "ВПН 2020 | Официальный сайт | Всероссийская перепись населения 2021". Archived from the original on 2023-01-30. Retrieved 2023-01-15.

- Ianbay, Iala (2016). Krymchak Dictionary. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. IX–XIV. ISBN 978-3-447-10541-5.

- Akiner, Shirin (1986). Islamic peoples of the Soviet Union : with an appendix on the non-Muslim Turkic peoples of the Soviet Union : an historical and statistical handbook (2nd ed.). London: KPI. p. 433. ISBN 0-7103-0188-X.

- Stampfer, Shaul (2013). "Did the Khazars Convert to Judaism?". Jewish Social Studies. 19 (3): 1–72. doi:10.2979/jewisocistud.19.3.1. S2CID 161320785. Project MUSE 547127.

- Bernstein, S. "S. K. Mirsky Memorial Volume" pp. 451–538. 1970

- Glazer, S. M. Piyyut and Pesah: Poetry and Passover, p. 11, 2013

- Ueber das Maḥsor nach Ritus Kaffa. Isaac Markon, 1909.

- Wolfish, Dan (12 March 1993). "The Ottawa Jewish Bulletin, vol. 57 iss. 11". The Ottawa Jewish Bulletin. 57 (11): 18. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Gabbay, Liat Klain (2019-09-11). Indigenous, Aboriginal, Fugitive and Ethnic Groups Around the Globe. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-78985-431-2. Archived from the original on 2022-05-09. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

Sources

- Blady, Ken. Jewish Communities in Exotic Places Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson Inc., 2000. pp. 115–130.