Historical criticism

Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text".[1] While often discussed in terms of Jewish and Christian writings from ancient times, historical criticism has also been applied to other religious and secular writings from various parts of the world and periods of history.

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The primary goal of historical criticism is to discover the text's primitive or original meaning in its original historical context and its literal sense or sensus literalis historicus. The secondary goal seeks to establish a reconstruction of the historical situation of the author and recipients of the text. That may be accomplished by reconstructing the true nature of the events that the text describes. An ancient text may also serve as a document, record or source for reconstructing the ancient past, which may also serve as a chief interest to the historical critic. In regard to Semitic biblical interpretation, the historical critic would be able to interpret the literature of Israel as well as the history of Israel.[2] In 18th century Biblical criticism, the term "higher criticism" was commonly used in mainstream scholarship[3] in contrast to "lower criticism". In the 21st century, historical criticism is the more commonly used term for higher criticism, and textual criticism is more common than the loose expression "lower criticism".[4]

Historical criticism began in the 17th century and gained popular recognition in the 19th and 20th centuries. The perspective of the early historical critic was rooted in Protestant Reformation ideology since its approach to biblical studies was free from the influence of traditional interpretation.[5] Where historical investigation was unavailable, historical criticism rested on philosophical and theological interpretation. With each passing century, historical criticism became refined into various methodologies used today: source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, tradition criticism, canonical criticism, and related methodologies.[2]

Methods

Historical-critical methods are the specific procedures[1] used to examine the text's historical origins, such as the time and place in which the text was written, its sources, and the events, dates, persons, places, things, and customs that are mentioned or implied in the text.[2]

Application

Application of the historical-critical method, in biblical studies, investigates the books of the Hebrew Bible as well as the New Testament. Historical critics compare texts to any extant contemporaneous textual artifacts, i.e., other texts written around the same time. An example is that modern biblical scholarship has attempted to understand the Book of Revelation in its 1st-century historical context by identifying its literary genre with Jewish and Christian apocalyptic literature.

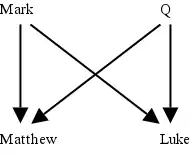

In regard to the Gospels, higher criticism deals with the synoptic problem, the relations among Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In some cases, such as with several Pauline epistles, higher criticism can confirm or challenge the traditional or received understanding of authorship. Higher criticism understands the New Testament texts within a historical context: that is, that they are not adamantine but writings that express the traditio (what is handed down). The truth lies in the historical context.

In classical studies, the 19th century approach to higher criticism set aside "efforts to fill ancient religion with direct meaning and relevance and devoted itself instead to the critical collection and chronological ordering of the source material."[6] Thus, higher criticism, whether biblical, classical, Byzantine or medieval, focuses on the source documents to determine who wrote it and where and when it was written.

Historical criticism has also been applied to other religious writings from Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism and Islam.

Methodologies

| * | includes most of Leviticus |

| † | includes most of Deuteronomy |

| ‡ | "Deuteronomic history": Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings |

Historical criticism comprises several disciplines, including[2] source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, tradition criticism, and radical criticism.

Source criticism

Source criticism is the search for the original sources which lie behind a given biblical text. It can be traced back to the 17th century French priest Richard Simon, and its most influential product is undoubtedly Julius Wellhausen's Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (1878), whose "insight and clarity of expression have left their mark indelibly on modern biblical studies."[7]

Form criticism

Form criticism breaks the Bible down into sections (pericopes, stories), which are analyzed and categorized by genres (prose or verse, letters, laws, court archives, war hymns, poems of lament etc.). The form critic then theorizes on the pericope's Sitz im Leben ("setting in life"), the setting in which it was composed and, especially, used.[8] Tradition history is a specific aspect of form criticism, which aims at tracing the way in which the pericopes entered the larger units of the biblical canon, especially the way in which they made the transition from oral to written form. The belief in the priority, stability and even detectability, of oral traditions is now recognised to be so deeply questionable as to render tradition history largely useless, but form criticism itself continues to develop as a viable methodology in biblical studies.[9]

Redaction criticism

Redaction criticism studies "the collection, arrangement, editing and modification of sources" and is frequently used to reconstruct the community and purposes of the authors of the text.[10]

History

Historical criticism as applied to the Bible began with Benedict Spinoza (1632–1677).[11] When it is applied to the Bible, the historical-critical method is distinct from the traditional, devotional approach.[12] In particular, while devotional readers concern themselves with the overall message of the Bible, historians examine the distinct messages of each book in the Bible.[12] Guided by the devotional approach, for example, Christians often combine accounts from different gospels into single accounts, but historians attempt to discern what is unique about each gospel, including how they differ.[12]

The phrase "higher criticism" became popular in Europe from the mid-18th century to the early 20th century to describe the work of such scholars as Jean Astruc (1684-1766), Johann Salomo Semler (1725–91), Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752–1827), Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792–1860), and Wellhausen (1844–1918).[13] In academic circles, it now is the body of work properly considered "higher criticism", but the phrase is sometimes applied to earlier or later work using similar methods.

"Higher criticism" originally referred to the work of German biblical scholars of the Tübingen School. After the groundbreaking work on the New Testament by Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), the next generation, which included scholars such as David Friedrich Strauss (1808–74) and Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–72), analyzed in the mid-19th century the historical records of the Middle East from biblical times, in search of independent confirmation of events in the Bible. The latter scholars built on the tradition of Enlightenment and Rationalist thinkers such as John Locke (1632–1704), David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Gotthold Lessing, Gottlieb Fichte, G. W. F. Hegel (1770–1831) and the French rationalists.

Such ideas influenced thought in England through the work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and, in particular, through George Eliot's translations of Strauss's The Life of Jesus (1846) and Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1854). In 1860, seven liberal Anglican theologians began the process of incorporating this historical criticism into Christian doctrine in Essays and Reviews, causing a five-year storm of controversy, which completely overshadowed the arguments over Charles Darwin's newly published On the Origin of Species. Two of the authors were indicted for heresy and lost their jobs by 1862, but in 1864, they had the judgement overturned on appeal. La Vie de Jésus (1863), the seminal work by a Frenchman, Ernest Renan (1823–1892), continued in the same tradition as Strauss and Feuerbach. In Catholicism, L'Evangile et l'Eglise (1902), the magnum opus by Alfred Loisy against the Essence of Christianity of Adolf von Harnack (1851–1930) and La Vie de Jesus of Renan, gave birth to the modernist crisis (1902–61). Some scholars, such as Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) have used higher criticism of the Bible to "demythologize" it.

John Barton argues that the term "historical-critical method" conflates two nonidentical distinctions, and prefers the term "Biblical criticism":

Historical study... can be either critical or noncritical; and critical study can be historical or nonhistorical. This suggests that the term "historical-critical method" is an awkward hybrid and might better be avoided.[14]

Evangelical objections

Beginning in the nineteenth century, effort on the part of evangelical scholars and writers was expended in opposing theories of historical critical scholars. Evangelicals at the time accused the 'higher critics' of representing their dogmas as indisputable facts. Bygone churchmen such as James Orr, William Henry Green, William M. Ramsay, Edward Garbett, Alfred Blomfield, Edward Hartley Dewart, William B. Boyce, John Langtry, D. K. Paton, John William McGarvey, David MacDill, J. C. Ryle, Charles Spurgeon and Robert D. Wilson pushed back against the judgements of historical critics. Some of these counter-views still have support in the more conservative evangelical circles today. There has never been a centralised stance on historical criticism, and Protestant denominations divided over the issue (e.g. Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy, Downgrade controversy etc.). The historical-grammatical method of biblical interpretation has been preferred by evangelicals, but is not held by the preponderance of contemporary scholars affiliated to major universities.[15] C. S. Lewis,[16] Gerhard Maier, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Robert L. Thomas, F. David Farnell, William J. Abraham, J. I. Packer, G. K. Beale and Scott W. Hahn rejected the historical-critical hermeneutical method as evangelicals.

Evangelical Christians have often partly attributed the decline of the Christian faith (i.e. declining church attendance, fewer conversions to faith in Christ and biblical devotion, denudation of the Bible's supernaturalism, syncretism of philosophy and Christian revelation etc.) in the developed world to the consequences of historical criticism. Acceptance of historical critical dogmas engendered conflicting representations of Protestant Christianity.[17] The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy in Article XVI affirms traditional inerrancy, but not as a response to 'negative higher criticism.'[18]

On the other hand, attempts to revive the extreme historical criticism of the Dutch Radical School by Robert M. Price, Darrell J. Doughty and Hermann Detering have also been met with strong criticism and indifference by mainstream scholars. Such positions are nowadays confined to the minor Journal of Higher Criticism and other fringe publications.[19]

See also

References

Citations

- Soulen, Richard N.; Soulen, R. Kendall (2001). Handbook of biblical criticism (3rd ed., rev. and expanded. ed.). Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-664-22314-1.

- Soulen, Richard N. (2001). Handbook of Biblical Criticism. John Knox. p. 79.

- Hahn, Scott, ed. (2009). Catholic Bible dictionary (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51229-9.

- Soulen, Richard N. (2001). Handbook of Biblical Criticism. John Knox. pp. 108, 190.

- Ebeling, Gerhard (1963). Word and Faith. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

- Burkert, Greek Religion (1985), Introduction.

- Antony F. Campbell, SJ, "Preparatory Issues in Approaching Biblical Texts Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine," in The Hebrew Bible in Modern Study, p. 6. Campbell renames source criticism as "origin criticism".

- "BibleDudes: Biblical Studies: Form". bibledudes.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- "Review of Biblical Literature" (PDF). www.bookreviews.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- "Religious Studies Department, Santa Clara University". Archived from the original on February 28, 2006.

-

Compare:

Durant, Will (1961) [1926]. "4: Spinoza". The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the Great Philosophers of the Western World. A Touchstone book. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 125. ISBN 9780671201593. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

...the movement of higher criticism which Spinoza initiated has made into platitudes the propositions for which Spinoza risked his life.

- Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus, Interrupted, HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 0-06-117393-2

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2007

- John Barton, The Nature of Biblical Criticism, Westminster John Knox Press (2007), p. 39.

- https://ehrmanblog.org/how-do-we-know-what-most-scholars-think/ Archived 2021-07-30 at the Wayback Machine Quote: "First, what is taught about the New Testament to undergraduates at the colleges and universities that are NOT evangelical? You can pick any type of school you want, and I (and virtually every other scholar in the field) can tell you the answer, simply because I (and they) know (either personally or through reputation) virtually every senior (and many junior) scholar at those places. These scholars pretty much all toe the line that I indicate: about John, 1 Timothy, the dating of the Gospels, and most other critical issues."

- Lewis, Clive Staples (1969). "Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism". BYU Studies Quarterly. 9 (1).

- "D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones on the Authority of Scripture—We Must Choose Between Two Positions". Albert Mohler. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Baptist Church, Duncan Street. "Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy". duncanstreetbaptistchurch.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2023-01-22. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2012-03-20). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-208994-6. Archived from the original on 2022-08-08. Retrieved 2021-11-17.

Sources

- Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J. American Catholic Biblical Scholarship: A History from the Early Republic to Vatican II, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1989, ISBN 0-06-062666-6. Nihil obstat by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., and Joseph A. Fitzmyer, S.J.

- Robert Dick Wilson. Is the Higher Criticism Scholarly? Clearly Attested Facts Showing That the Destructive "Assured Results of Modern Scholarship" Are Indefensible. Philadelphia: The Sunday School Times, 1922. 62 pp.; reprinted in Christian News 29, no. 9 (4 March 1991): 11–14.

External links

- Rutgers University: Synoptic Gospels Primer: introduction to the history of literary analysis of the Greek gospels, and aids in confronting the range of factors that need to be taken into consideration in accounting for the literary relationship of the first three gospels.

- Journal of Higher Criticism

- From the Divine Oracle to Higher Criticism

- Catholic Encyclopedia article "Biblical Criticism (Higher)"

- Dictionary of the history of Ideas – Modernism and the Church

- Dictionary of the history of Ideas: Modernism in the Christian Church

- Teaching Bible based on Higher Criticism

- "Historical Criticism and the Evangelical" by Grant Osborne

- "From the Divine Oracle to Higher Criticism" from The Warfare of Science With Theology by Andrew White, 1896

- Catholic Encyclopedia article (1908) "Biblical Criticism (Higher)"

- Radical criticism, link to articles in English

- Library of latest modern books of biblical studies and biblical criticism