Hillbilly

Hillbilly is a term for people who dwell in rural, mountainous areas in the United States, primarily in the Appalachian region. As people migrated out of the region during the Great Depression, the term spread northward and westward with them.

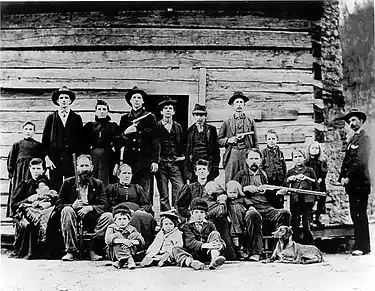

The first known instances of "hillbilly" in print were in The Railroad Trainmen's Journal (vol. ix, July 1892),[1] an 1899 photograph of men and women in West Virginia labeled "Camp Hillbilly",[2] and a 1900 New York Journal article containing the definition: "a Hill-Billie is a free and untrammeled white citizen of Alabama, who lives in the hills, has no means to speak of, dresses as he can, talks as he pleases, drinks whiskey when he gets it, and fires off his revolver as the fancy takes him".[3] The stereotype is twofold in that it incorporates both positive and negative traits: "Hillbillies" are often considered independent and self-reliant individuals who resist the modernization of society, but at the same time they are also defined as backward and violent. Scholars argue this duality is reflective of the split ethnic identities in white America.[2] The term's later usage extended beyond solely white communities, exemplified with the "Hispanic hillbillies of northern New Mexico," in reference to the Hispanos of New Mexico.[4]

Etymology

The term "hillbilly" is Scottish in origin but is not derived from its dialect. In Scotland, the term "hill-folk" referred to people who preferred isolation from the greater society, and "billy" meant "comrade" or "companion". The words "hill-folk" and "Billie" were combined and applied to the Cameronians who followed the teachings of a militant Presbyterian named Richard Cameron. These Scottish Covenanters fled to the hills of southern Scotland in the late 17th century to avoid persecution of their religious beliefs.[5]

Many of the early settlers of the Thirteen Colonies were from Scotland and Northern Ireland and were followers of William of Orange, the Protestant king of England. In 17th century Ireland, during the Williamite War, protestant supporters of William III ("King Billy") were referred to as "Billy's Boys" because 'Billy' is a diminutive of 'William' (common across both Britain and Ireland). In time the term hillbilly became synonymous with the Williamites who settled in the hills of North America.[6]

Some scholars disagree with this theory. Michael Montgomery's From Ulster to America: The Scotch-Irish Heritage of American English states, "In Ulster in recent years it has sometimes been supposed that [hillbilly] was coined to refer to followers of King William III and brought to America by early Ulster emigrants, but this derivation is almost certainly incorrect. ... In America hillbilly was first attested only in 1898, which suggests a later, independent development."[7]

History

The Appalachian Mountains were settled in the 18th century by settlers primarily from England, lowland Scotland, and the province of Ulster in Ireland. The settlers from Ulster were mainly Protestants who migrated to Ireland from Lowland Scotland and Northern England during the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century. Many further migrated to the American colonies beginning in the 1730s, and in America became known as the Scots-Irish although this term is inaccurate as they were also of Northern English descent.[7]

The term "hillbilly" spread in the years following the American Civil War. At this time, the country was developing both technologically and socially, but the Appalachian region was falling behind. Before the war, Appalachia was not distinctively different from other rural areas of the country. Post-war, although the frontier pushed farther west, the region maintained frontier characteristics. The Appalachian people themselves were perceived as backward, quick to violence, and inbred in their isolation. Fueled by news stories of mountain feuds such as that in the 1880s between the Hatfields and McCoys, the hillbilly stereotype developed in the late 19th to early 20th century.[2]

The term "hillbilly" was used by members of the Planter's Protection Association, a tobacco farmers union that formed in the Black Patch region of Kentucky, to refer to non-union scab farmers who did not join the organization.[8]

The "classic" hillbilly stereotype reached its current characterization during the years of the Great Depression. The period of Appalachian out-migration, roughly from the 1930s through the 1950s, saw many mountain residents moving north to the Midwestern industrial cities of Chicago, Cleveland, Akron, and Detroit.

This movement to Northern society, which became known as the "Hillbilly Highway", brought these previously isolated communities into mainstream United States culture. In response, poor white mountaineers became central characters in newspapers, pamphlets, and eventually, motion pictures. Authors at the time were inspired by historical figures such as Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone. The mountaineer image transferred over to the 20th century where the "hillbilly" stereotype emerged.[2]

In popular culture

Pop culture has perpetuated the "hillbilly" stereotype. Scholarly works suggest that the media has exploited both the Appalachian region and people by classifying them as "hillbillies". These generalizations do not match the cultural experiences of Appalachians. Appalachians, like many other groups, do not subscribe to a single identity.[9] One of the issues associated with stereotyping is that it is profitable. When "hillbilly" became a widely used term, entrepreneurs saw a window for potential revenue. They "recycled" the image and brought it to life through various forms of media.[10]

The comics portrayed hillbilly stereotypes, notably in two strips, Li'l Abner and Snuffy Smith. Both characters were introduced in 1934.

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (2016) is a memoir by J. D. Vance about the Appalachian values of his upbringing and their relationship to the social problems of his hometown, Middletown, Ohio. The book topped The New York Times Best Seller list in August 2016.[11]

A family of "Hill People", who are employed as migrant workers on a farm in 1952 Arkansas, have a major role in John Grisham's book A Painted House, with Grisham trying to avoid stereotypes.

Film and television

Television and film have portrayed "hillbillies" in both derogatory and sympathetic terms. Films such as Sergeant York or the Ma and Pa Kettle series portrayed the "hillbilly" as wild but good-natured. Television programs of the 1960s such as The Real McCoys, The Andy Griffith Show, and especially The Beverly Hillbillies, portrayed the "hillbilly" as backwards but with enough wisdom to outwit more sophisticated city folk. Gunsmoke's Festus Haggen was portrayed as intelligent and quick-witted (but lacking "education").

The popular 1970s television variety show Hee Haw regularly lampooned the stereotypical "hillbilly" lifestyle. A darker negative image of the hillbilly was introduced to another generation in the film Deliverance (1972), based on a novel of the same name by James Dickey, which depicted some "hillbillies" as genetically deficient, inbred, and murderous.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and its sequels has Leatherface and his family, the Sawyers, portray a particularly violent "Hillbilly" stereotype that is common in horror films. The trope that comes from the depiction of Hillbillies and inbred, cannibalistic savages is called the "Hillbilly Horrors" trope.[12] The Texas Chainsaw Massacre movie series is thought to have paved the way for the countless horror films featuring deranged and often cannibalistic "Hillbillies" that have since become a staple of the horror genre.[13]

Similar "evil hillbilly people"-type have also been seen in a more comical light in the 1988 horror film The Moonlight Sonata, but the 2010 horror comedy film Tucker & Dale vs. Evil even parodies hillbilly stereotyping. More recently, the TV series Justified (2010-2015) was centered around deputy U. S. Marshal Raylan Givens who was reassigned to his hometown in Harlan, Kentucky where he was in conflict with Boyd Crowder, a drug dealer who had grown up with Raylan. The show's plots often included "hillbilly" tropes such as dimwitted and easily manipulated men, use of homemade drugs, and snake-handling revivalists.

"Hillbillies" became a frequent gimmick in professional wrestling, usually portrayed as simple but amiable fan favourites. An early example of this character was Whiskers Savage (born Edward Civil, 1899-1967) who was promoted as a "bumpkin" persona as early as 1928.[14] During the 1960s and 1970s, two superheavyweight wrestlers (and frequent tag team partners) Haystacks Calhoun and Man Mountain Mike both portrayed "country boys" in overalls and carrying lucky horseshoes. In the WWF in the 1980s, Hillbilly Jim, depicted as a protegé of Hulk Hogan, led a faction of "hillbillies" including Uncle Elmer, Cousin Luke and Cousin Junior.[15][16]

"Hillbillies" were at the center of reality television in the 21st century. Network television shows such as The Real Beverly Hillbillies, High Life, and The Simple Life displayed the "hillbilly" lifestyle for viewers in the United States. This sparked protests across the country with rural-minded individuals gathering to fight the stereotype. The Center for Rural Strategies started a nationwide campaign stating the stereotype was "politically incorrect". The Kentucky-based organization engaged political figures in the movement such as Robert Byrd and Mike Huckabee. Both protestors argued that the discrimination of any other group in United States would not be tolerated, so neither should the discrimination against rural U.S. citizens. A 2003 piece published by The Cincinnati Enquirer read, "In this day of hypersensitivity to diversity and political correctness, Appalachians have been a group that it is still socially acceptable to demean and joke about... But rural folks have spoken up and said 'enough' to the Hollywood mockers."[17]

Music

Hillbilly music was at one time considered an acceptable label for what is now known as country music. The label, coined in 1925 by country pianist Al Hopkins,[18] persisted until the 1950s.

The "hillbilly music" categorization covers a wide variety of musical genres including bluegrass, country, western, and gospel. Appalachian folk song existed long before the "hillbilly" label. When the commercial industry was combined with "traditional Appalachian folksong", "hillbilly music" was formed. Some argue this is a "High Culture" issue where sophisticated individuals may see something considered "unsophisticated" as "trash".[5]

In the early-20th century, artists began to utilize the "hillbilly" label. The term gained momentum due to Ralph Peer, the recording director of OKeh Records, who heard it being used among Southerners when he went down to Virginia to record the music and labeled all Southern country music as so from then on.[19] The York Brothers entitled one of their songs "Hillbilly Rose" and the Delmore Brothers followed with their song "Hillbilly Boogie". In 1927, the Gennett studios in Richmond, Indiana, made a recording of black fiddler Jim Booker. The recordings were labeled "made for Hillbilly" in the Gennett files and were marketed to a white audience. Columbia Records had much success with the "Hill Billies" featuring Al Hopkins and Fiddlin' Charlie Bowman.

By the late-1940s, radio stations started to use the "hillbilly music" label. Originally, "hillbilly" was used to describe fiddlers and string bands, but now it was used to describe traditional Appalachian music. Appalachians had never used this term to describe their own music. Popular songs whose style bore characteristics of both hillbilly and African American music were referred to as hillbilly boogie and rockabilly. Elvis Presley was a prominent player of rockabilly and was known early in his career as the "Hillbilly Cat".

When the Country Music Association was founded in 1958, the term hillbilly music gradually fell out of use. The music industry merged hillbilly music, Western swing, and Cowboy music, to form the current category C&W, Country and Western.

Some artists (notably Hank Williams) and fans were offended by the "hillbilly music" label. While the term is not used as frequently today, it is still used on occasion to refer to old-time music or bluegrass. For example, WHRB broadcasts a popular weekly radio show entitled "Hillbilly at Harvard". The show is devoted to playing a mix of old-time music, bluegrass, and traditional country and western.[20]

Video games

Many video games feature plots, subplots or characters that utilize the Hillbilly stereotype for narrative purposes and cultural signifiers. Some notable examples of this include the Silent Hill video game series, Fallout 3, Fallout 76, Dead by Daylight, Grand Theft Auto V, Red Dead Redemption 2, Resident Evil 4 and Resident Evil 7.

Cultural implications

The hillbilly stereotype is considered to have had a traumatizing effect on some in the Appalachian region. Feelings of shame, self-hatred, and detachment are cited as a result of "culturally transmitted traumatic stress syndrome". Appalachian scholars say that the large-scale stereotyping has rewritten Appalachian history, making Appalachians feel particularly vulnerable. "Hillbilly" has now become part of Appalachian identity and some Appalachians feel they are constantly defending themselves against this image.[9]

The stereotyping also has political implications for the region. There is a sense of "perceived history" that prevents many political issues from receiving adequate attention. Appalachians are often blamed for economic struggles. "Moonshiners, welfare cheats, and coal miners" are stereotypes stemming from the greater hillbilly stereotype in the region. This prejudice has been said to serve as a barrier for addressing some serious issues such as the economy and the environment.[9]

Despite the political and social difficulties associated with stereotyping, Appalachians have organized to enact change. The War on Poverty is sometimes considered to be an example of one effort that allowed for Appalachian community organization. Grassroots movements, protests, and strikes are common in the area, though not always successful.[9]

Intragroup versus intergroup usage

The Springfield, Missouri Chamber of Commerce once presented dignitaries visiting the city with an "Ozark Hillbilly Medallion" and a certificate proclaiming the honoree a "hillbilly of the Ozarks". On June 7, 1952, President Harry S. Truman received the medallion after a breakfast speech at the Shrine Mosque for the 35th Division Association.[21] Other recipients included US Army generals Omar Bradley and Matthew Ridgway, J. C. Penney, Johnny Olson, and Ralph Story.[22]

Hillbilly Days[23] is an annual festival held in mid-April in Pikeville, Kentucky celebrating the best of Appalachian culture. The event began by local Shriners as a fundraiser to support the Shriners Children's Hospital. It has grown since its beginning in 1976 and now is the second largest festival held in the state of Kentucky. Artists and craftspeople showcase their talents and sell their works on display. Nationally renowned musicians as well as the best of the regional mountain musicians share six different stages located throughout the downtown area of Pikeville. Aspiring hillbillies from across the nation compete to come up with the wildest Hillbilly outfit. The event has earned its name as the Mardi Gras of the Mountains. Fans of "mountain music" come from around the United States to hear this annual concentrated gathering of talent. Some refer to this event as the equivalent of a "Woodstock" for mountain music.

The term "Hillbilly" has been used with pride by a number of people within the region as well as famous persons, such as singer Dolly Parton, chef Sean Brock, and actress Minnie Pearl. Positive self-identification with the term generally includes identification with a set of "hillbilly values" including love and respect for nature, strong work ethic, generosity toward neighbors and those in need, family ties, self-reliance, resiliency, and a simple lifestyle.

See also

References

- "Hillbilly". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- Harkins, Anthony (November 20, 2003). Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195146318.

- Hawthorne, Julian (April 23, 1900). "Mountain Votes Spoil Huntington's Revenge". New York Journal: 2.

- Verbatim. 1995. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- Green, Archie (1965). "Hillbilly Music: Source and Symbol". Journal of American Folklore. 78 (309): 204–228. doi:10.2307/538356. JSTOR 538356.

- "Hillbillies in the White House". BBC News.

- Montgomery, Michael (2006). From Ulster to America: The Scotch-Irish Heritage of American English. Ulster Historical Foundation. p. 82. ISBN 9781903688618.

- "Brutal Saviours of the Black Patch | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- Billings, Dwight B.; Norman, Gurney; Ledford, Katherine (2000). Back Talk from Appalachia: Confronting Stereotypes. ISBN 978-0813143347. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- Newcomb, Horace (1979). "Appalachia on Television: Region as Symbol in American Popular Culture". Appalachian Journal. 7 (1/2): 155–164. JSTOR 40932731.

- Aaron M. Renn (August 23, 2016). "Hillbilly Elegy: Culture, Circumstance, Agency". Urbanophile. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- "Hillbilly Horrors". TV Tropes. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- Knöppler, Christian (2017). ""7. Cannibal Hillbillies and Backwoods Horror"". The Monster Always Returns: American Horror Films and Their Remakes: 183–210. doi:10.1515/9783839437353-010. ISBN 9783839437353 – via Degruyter.

- "Leo Savage". Wrestlingdata.com. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- Murphy, Ryan (December 8, 2010). "Where Are They Now? Hillbilly Jim". WWE.com. WWE. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Hillbilly Jim". WWE.com. WWE. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Pate, Susan (2008). Grappling With Diversity Readings On Civil Rights Pedagogy and Critical Multiculturalism. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791478998.

- Sanjek, David (2004). "All the Memories Money Can Buy: Marketing Authenticity and Manufacturing Authorship". In Eric Weisbard (ed.). This is Pop. Harvard University Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-674-01321-6.

- Brackett, David. The Pop, Rock and Soul Reader: Histories and Debates.

- Potier, Beth. "'Hillbilly at Harvard' hosts heady hoedown weekly". Harvard University Gazette. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- "Remarks at a Breakfast of the 35th Division Association, Springfield, Missouri". June 7, 1952. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Dessauer, Phil "Springfield, Mo.-Radio City of Country Music" (April, 1957), Coronet, p. 151

- "Hillbilly days".

African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A Study of Folk Tradition (1995), by Cecelia Conway