History of Cape Verde

The recorded history of Cape Verde begins with the Portuguese discovery of the island in 1458. Possible early references to Cape Verde date back at least 2,000 years.

| History of Cape Verde |

|---|

|

| Colonial history |

| Independence struggle |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Cape Verde |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Prehistory

The first islands formed, around 40-50 million years ago, were present-day Sal and its eastern neighbors. The western islands were formed later, including São Nicolau (as early as 11.8 million years ago), São Vicente (nine million years ago), present-day Santiago and Fogo (four million years ago), and Brava (two to three million years ago).[1][2] Millions of years after the seamounts rose above the Atlantic, the first lizards, insects and plants came to the archipelago, possibly on ocean currents from the African mainland when the ocean's salinity was lower.[3]

The archipelago experienced several large volcanic eruptions, including Praia Grande 4.5 million years ago, São Vicente (and, possibly, present-day Porto Grande) 300,000 years ago,[4] Topo da Coroa 200,000 years ago, and east of present-day Fogo 73,000 years ago which inundated coastal Santiago Island and possibly Brava and part of the Barlavento Islands.[5]

During the last Ice Age, the sea level dropped to about 130 meters below its current level. Cape Verde's islands were slightly larger, and there was a large island known as Northwest Island. Santo Antão was one kilometer northwest of the island; Boa Vista and Maio were one island, and another island known as Nola (Ilha da Nola, northwest of Santo Antão) was about 80–90 meters above sea level. Before the end of the Ice Age, the Eastern Island (Ilha Occidental) split into three islands; one became submerged and is now the João Valente Reef, the Canal de São Vicente widened to provide 12 km separation from Santo Antão, Nola Island was submerged and again became a seamount, and eastern Northwest Island broke up into São Vicente, the smaller Santa Luzia, and the two islets of Branco and Raso.[6]

Possible classical references

Cape Verde may have been referenced in De choreographia by Pomponius Mela and Historia naturalis by Pliny the Elder. Mela and Pliny called the islands "Gorgades", referring to the home of the mythical Gorgons killed by Perseus. In typical ancient euhemerism, they suggested the islands as the place where the Carthaginian Hanno the Navigator slew two female "Gorillai" whose skins Hanno brought back to Carthage.

Pliny, citing the Greek writer Xenophon of Lampsacus, placed the Gorgades at two days' travel from "Hesperu Ceras" (the westernmost part of the African continent, today called Cap-Vert). As quoted by Gaius Julius Solinus, he also said that the voyage from the Gorgades to the Hesperides took around 40 days.[7] The Isles of the Blessed, written about by Marinus of Tyre and referenced by Ptolemy in his Geographia, may have been the Cape Verde islands.[8]

Portuguese discovery and colonisation

.svg.png.webp)

15th and 16th centuries

In 1456, in the service of Prince Henry the Navigator, Alvise Cadamosto, Antoniotto Usodimare (Venetian and Genoese captains, respectively) and an unnamed Portuguese captain discovered some of the islands. During the next decade, Diogo Gomes and António de Noli (also captains in the service of Prince Henry) discovered the remaining islands of the archipelago. When they first landed in Cape Verde, the islands were barren of people but not of vegetation. The Portuguese returned six years later to the island of São Tiago to establish Ribeira Grande (present-day Cidade Velha) in 1462—the first permanent European settlement in the tropics.

In Spain, the Reconquista was growing in its mission to conquer Iberia and expel the Muslims and Jews. In 1492, the Spanish Inquisition also emerged in its fullest expression of anti-Semitism. It spread to neighboring Portugal (as the Portuguese Inquisition), where King João II and Manuel I exiled thousands of Jews to São Tomé, Príncipe, and Cape Verde in 1496.

The Portuguese soon brought slaves from the West African coast. Positioned on trade routes between Africa, Europe, and the New World, the archipelago prospered from the transatlantic slave trade during the 16th century. Settlements began to appear on other islands. São Filipe was founded in 1500; Ponta do Sol and Ribeira Grande were founded in the mid-16th century (when its first settlers also arrived in Madeira and Ribeira Brava on São Nicolau. Povoação Velha on Boa Vista, Furna, Nova Sintra on Brava, and Palmeira on Sal were later founded.

The islands' prosperity encouraged sacking by pirates. After the Philippine dynasty began, Sir Francis Drake sacked Ribeira Grande in 1582, captured the island in 1585 and raided Cidade Velha, Praia and São Domingos. A year later, Cape Verde became a colony of Portugal.

17th and 18th centuries

The city of Praia was founded in 1613 on the plateau of a previous settlement. Pico do Fogo erupted in 1680, which resulted in the movement of the population to Brava and other regions (including Brazil). For a few years, the volcano was a natural lighthouse for sailors.

During the 17th century, Algerian corsairs established a base on the Cape Verde islands. They raided Madeira in 1617, stealing the church bells and taking 1,200 people captive.[9] As a result of the 1712 French Cassard expedition in which Ribeira Grande was destroyed, the capital was partially moved to Praia in the east; it became the capital in 1770. By 1740, the island was a supply point for American slave ships and whalers. This began a stream of male immigration to the American colonies.

In 1747, the islands were hit with the first of several droughts and famines which have plagued them ever since at average five-year intervals. The situation was made worse by deforestation and overgrazing, which destroyed the ground vegetation that provided moisture. Three major droughts during the 18th and 19th centuries resulted in well over 100,000 people starving to death. The Portuguese government sent little relief during the droughts.[10][11][12]

Given the scarcity of capital for the region's development, the Portuguese Finance and Overseas Councils authorized the 1664 foundation of the Guinea Coast Company. The company aimed at the slave trade, ending individual tenancy and encouraging slave companies. The Company of Cacheu and Rivers and Commerce of Guinea, which operated between 1676 and 1682, was succeeded by the Company of Cacheu and Cape Verde in 1690.

Textiles were smuggled and sold on the black market, since their values were high and their origins difficult to prove. Between 1766 and 1776, 95,000 "barafulas" (Cape Verdean textiles) were imported to the Guinean coast.

Pico do Fogo again erupted in 1769. This was the last time it erupted from the top, although it also erupted in 1785 and 1799. Another famine, affecting Brava and Fogo, began in 1774; 20,000 people starved. Fogo's population dropped from 5,700 to 4,200 around 1777. The first wave of emigration began from the islands of Brava and Fogo, as American whaling ships visited the islands and some residents left for a better life in the United States. Praia became the colonial capital in 1770, and remained so until Cape Verdean independence. Although Portugal was neutral in the Anglo-French War and American Revolutionary War, British and French squadrons fought the Battle of Porto Praya off present-day Praia on 16 April 1781.

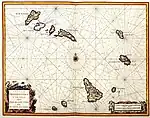

1683 map of the Cape Verde islands

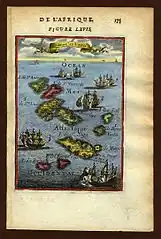

1683 map of the Cape Verde islands.jpg.webp) 1747 French-Dutch map of Cape Verde by Jacques Nicolas Bellin

1747 French-Dutch map of Cape Verde by Jacques Nicolas Bellin The 1781 battle of Porto Praya by Marquis de Rossel

The 1781 battle of Porto Praya by Marquis de Rossel

19th century

_p098_PORTO_PRAYA%252C_ISLAND_OF_ST.JAGO.jpg.webp)

The 19th-century decline of the slave trade dealt a blow to Cape Verde's economy. Around this time, Cape Verdeans began emigrating to New England. Whales abounded in the waters around Cape Verde, and as early as 1810 whaling ships from Massachusetts and Rhode Island recruited crews from the islands of Brava and Fogo.

The last pirate raids, including one in Sal Rei in 1815, led to the building of several forts across Cape Verde. Other settlements were founded later, including Mindelo (originally Nossa Senhora da Luz) in 1795, Pedra de Lume on Sal in 1799, and Santa Maria in early 1830 on the same island. Praia (the colonial capital) was modernized in 1822, expanding northward.

After Portugal lost Brazil, the British used Mindelo to refuel ships and the city flourished in 1838. Two attempts to move the colonial capital from Praia were made: a plan to move to Picos in 1831 when another famine struck Cape Verde, and Mindelo was decided on in 1838. Many people did not want to move the colonial capital, and it remained in Praia. Fogo again erupted in 1847, 1852, and 1857. Mindelo grew; two submarine telegraph cables were linked in 1874 to Pernambuco Brazil]] (when the Cory brothers opened) and to Cameroon via Bathurst (present-day Banjul) in the Gambia in 1885. Mindelo became the most-used transatlantic telegraph station in 1912. A total of 669 ships were refueled each year at the port, reaching 1,927 ships a decade later. When gasoline began to be used on boats, however, Mindelo could not rival the ports of Las Palmas on Grand Canary or nearby Dakar in Senegal. The use of coal declined, leading to a coal strike in 1912 due to insufficient work; when the Great Depression began in 1930, ship activity ended. Slavery disappeared in Cape Verde, first in São Vicente, then São Nicolau, Santo Antão and Boa Vista in 1867 (when the slave trade ended in Portugal) before ending throughout Cape Verde.[13]

_-_1885.jpg.webp) Capo Verdeans in 1885

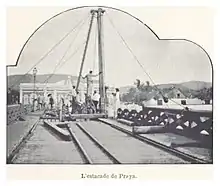

Capo Verdeans in 1885 Port of Praia, 1899

Port of Praia, 1899 Praia market, 1899

Praia market, 1899 Praia maize mill, 1899

Praia maize mill, 1899 Square in Praia, 1899

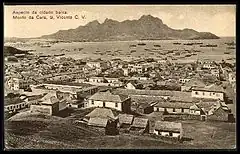

Square in Praia, 1899 Praia in 1899

Praia in 1899

20th century

At the end of the 19th century, with the advent of the ocean liner, the island's position on the Atlantic shipping lanes made Cape Verde a location for resupplying ships with fuel (imported coal), water and other supplies. Because of its harbour (developed by British merchants), Mindelo became a 19th-century commercial centre for British companies which used Cape Verde as a storage depot for coal bound for the Americas. The island of São Vicente housed a coaling and submarine cable station employing local labourers.

During World War II, Royal Navy ships were stationed in Mindelo. In April 1941, due to Winston Churchill's interest in Cape Verde, thousands of Allied troops were stationed on São Vicente. After the war, the economy collapsed as shipping traffic was reduced.

Espargos, in the centre of the island of Sal was founded in the late 1940s as the last Portuguese airport town. From 1950 to 1970, the number of flights increased. Espargos became an important stop for Alitalia's Portuguese-Brazilian flights and South African Airways' (SAA) 1967 flights between London and Johannesburg. The airline had to use the airport because to the international boycott of South Africa due to its apartheid policy.

In 1952, the Portuguese government planned to transfer over 10,000 settlers to the island of São Tomé in São Tomé and Príncipe (another Portuguese colony) to work on plantations. Africans came primarily from the islands of São Nicolau, Santiago, Santo Antão, Fogo, and Brava. When the two colonies became independent, many people left for Europe and the United States, and few returned to Cape Verde. Several famines occurred at this time due to poor harvests, the Second World War, and a poor response from the Portuguese colonial administration. Until and during the Portuguese Colonial War, those planning and fighting in the armed conflict in Portuguese Guinea often linked the liberation of Guinea-Bissau to liberation in Cape Verde; in 1956, Amílcar and Luís Cabral founded the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde.[14]

Independence movement

Although Cape Verde was neglected by Portugal, Portuguese treatment of Cape Verdeans was differed from their treatment of other colonized peoples;[15] the people of Cape Verde fared slightly better than Africans in other Portuguese colonies because of their lighter skin. A small minority received an education, and Cape Verde was the first African-Portuguese colony to have an institution of higher education. By the time of independence, one-quarter of the population could read (compared to five percent in Portuguese Guinea, present-day Guinea-Bissau).

Literate Cape Verdeans became aware of the pressures for independence which were building on the mainland. The islands continued experiencing droughts, famines, epidemics and volcanic eruptions amid Portuguese government indifference. Thousands of people died of starvation during the first half of the 20th century. Although the nationalist movement appeared less fervent in Cape Verde than in Portugal's other African holdings, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or PAIGC) was founded in 1956 by Amílcar Cabral and other pan-Africanists. Many Cape Verdeans fought for independence in Guinea-Bissau.[16]

In 1926, Portugal had become a rightist dictatorship which regarded the colonies as an economic frontier to be developed in the interest of Portugal and the Portuguese. Famines, unemployment, poverty, and the failure of the Portuguese government to address those issues caused resentment, but Portuguese dictator António de Oliveira Salazar did not want to give up his colonies as easily as other European colonial powers had given up theirs.

After World War II, Portugal was intent on holding onto its former colonies (known since 1951 as overseas territories). When most former African colonies gained independence between 1957 and 1964, the Portuguese still held on. After the Pijiguiti Massacre, however, the people of Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau fought one of the longest African liberation wars.

Like other colonies, autonomy was granted in 1972 and Portuguese Cape Verde held its only parliamentary elections in 1973 in which only Portuguese citizens could vote. Only 25,521 people registered to vote out of a total population of 272,071, and a total of 20,942 people voted. The Portuguese constitution banned political parties at the time, and most of the candidates were put forward by the ruling People's National Action movement; some civic associations, however, were allowed to nominate candidates.

After the 25 April 1974 Carnation Revolution, Cape Verde became more autonomous but continued to have an overseas governor until that post became a high commissioner. Widespread unrest forced the government to negotiate with the PAIGC, and agreements for an independent Cape Verde were on the table. Pedro Pires returned to Praia on 13 October after being exiled for over a decade. After his return, Portugal signed the 1975 Algiers Agreement. On 5 July in Praia, Portuguese Prime Minister Vasco Gonçalves transferred power to National Assembly President Abilio Duarte. The colonial history of Cape Verde ended when Cape Verde become independent. There was no armed conflict in Cape Verde, and its independence resulted from negotiation with Portugal.[17] The catalyst for independence was the PAIGC branch in Guinea-Bissau, which began an ultimately-successful war against the Portuguese there; this eventually compelled Portugal to accept independence for Cape Verde as well.

After independence (1975)

One-party rule

First Republic of Cape Verde | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1991 | |||||||||

| Motto: Unidade, Trabalho, Progresso (Portuguese) "Unity, Labour, Progress" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Esta É a Nossa Pátria Bem Amada (English: "This Is Our Beloved Motherland") | |||||||||

.svg.png.webp) | |||||||||

| Capital | Praia | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary one-party socialist republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1975-1991 | Aristides Pereira | ||||||||

| Prime minister | |||||||||

• 1975-1991 | Pedro Pires | ||||||||

| Legislature | National People's Assembly | ||||||||

| Historical era | Decolonisation of Africa, Cold War | ||||||||

• Independence from Portugal | 5 July 1975 | ||||||||

• Established one-party state | 1981 | ||||||||

• Return to multiple parties | 28 September 1990 | ||||||||

| 13 January 1991 | |||||||||

| 17 February 1991 | |||||||||

| Currency | Escudo (CVE) | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | CV | ||||||||

| |||||||||

.svg.png.webp)

Immediately after a November 1980 coup in Guinea-Bissau (Portuguese Guinea declared independence in 1973 and was granted de jure independence in 1974), relations between the two countries became strained. Cape Verde abandoned its hope for unity with Guinea-Bissau, and formed the African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV).

Responding to growing pressure for a political opening, the PAICV called an emergency congress in February 1990 to discuss proposed constitutional changes to end one-party rule. Opposition groups came together to form the Movement for Democracy (MpD) in Praia in April of that year, and campaigned for the right to contest the presidential election scheduled for December 1990. The one-party state was abolished on 28 September of that year, and the first multi-party elections were held in January 1991.

End of one-party rule

The MpD won a majority of the seats in the National Assembly. MpD presidential candidate António Mascarenhas Monteiro defeated the PAICV candidate, 73.5 percent to 26.5 percent. Legislative elections in December 1995 increased the MpD majority in the National Assembly, where the party held 50 of its 72 seats. A February 1996 presidential election returned Monteiro to office.

In the presidential election campaign of 2000 and 2001, two former prime ministers (Pedro Pires and Carlos Veiga) were the main candidates. Pires was prime minister during the PAICV regime; Veiga was prime minister during most of Monteiro's presidency, stepping aside to campaign. In what might have been one of the closest races in electoral history, Pires won by 12 votes; he and Veiga each received nearly half the votes.[18] Pires was narrowly re-elected in the 2006 elections.[19]

Jorge Carlos Almeida Fonseca, President of Cape Verde since 2011, was re-elected in October 2016. Fonseca was supported by the Movement for Democracy (MpD). MpD leader Ulisses Correia e Silva has been prime minister since the 2016 elections, when his party ousted the ruling PAICV for the first time in 15 years.[20]

In October 2021, opposition candidate and former prime minister Jose Maria Neves of PAICV won Cape Verde's presidential election.[21] On 9 November of that year, Neves was sworn in as president.[22]

See also

Footnotes

- Brown, Emma (2015). "Island boulders reveal ancient mega-tsunami". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18485. S2CID 182938906.

- Sea level rise

- "Sea Level Rise | Smithsonian Ocean". 30 April 2018.

- Ramalho, R (2010). "Traces of uplift and subsidence in the Cape Verde Archipelago" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society. 167 (3): 519–538. Bibcode:2010JGSoc.167..519R. doi:10.1144/0016-76492009-056. S2CID 140566236.

- Brown, Emma (2 October 2015). "Island Boulders Reveal Ancient Megatsunami". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18485. S2CID 182938906. Retrieved 2015-10-06.

- "Cape Verde – Addis Herald".

- Collins, Andrew (2016-09-15). Atlantis in the Caribbean: And the Comet That Changed the World. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59143-266-1.

- Analysis of Ptolemy's Geographia

- Clark, G.N. (1944). "The Barbary Corsairs in the Seventeenth Century". The Cambridge Historical Journal. 8 (1): 23. doi:10.1017/S1474691300000561. JSTOR 3020800.

- Patterson, K. David (1988). "Epidemics, Famines, and Population in the Cape Verde Islands, 1580-1900". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 21 (2): 291–313. doi:10.2307/219938. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 219938. PMID 11617208.

- Christiano José, de Senna Barcellos (1900). Subsidios para a historia de Cabo Verde e Guiné. pp. 395–397, 401. OCLC 504707074.

- José Conrado Carlos, de Chelmicki. Corografía cabo-verdiana, ou, Descripção geographico-historica da provincia das Ilhas de Cabo-Verde e Guiné. p. 316. OCLC 956405163.

- "The Portuguese Colonization of Cape Verde".

- "Cabo Verde | South African History Online".

- Chabal, Patrick (1993). "Some reflections on the postcolonial state in Portuguese-speaking Africa". Africa Insight. 23: 129–135.

- See, for instance, Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1989, p. 399.

- António Costa Pinto, "The transition to democracy and Portugal's decolonization", in Stewart Lloyd-Jones and António Costa Pinto (eds., 2003). The Last Empire: Thirty Years of Portuguese Decolonization (Intellect Books, ISBN 978-1-84150-109-3) pp. 22–24.

- "Pedro Pires wins Cape Verde runoff". New Bedford Standard-Times.

- "Cape Verde profile - Timeline". BBC News. 8 May 2018.

- "Cape Verde country profile". BBC News. 5 December 2018.

- Rodrigues, Julio (18 October 2021). "Opposition candidate Neves wins Cape Verde election". Reuters.

- "Jose Maria Neves sworn in as new Cape Verde president". 9 November 2021.

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Cape Verde Historical Timeline by Raymond Almeida. alternative site

.svg.png.webp)