History of Nigeria

The history of Nigeria can be traced to the earliest inhabitants whose remains date from at least 13,000 BC through early civilizations such as the Nok culture which began around 1500 BC. Numerous ancient African civilizations settled in the region that is known today as Nigeria, such as the Kingdom of Nri,[1] the Benin Empire,[2] and the Oyo Empire.[3] Islam reached Nigeria through the Bornu Empire between (1068 AD) and Hausa States around (1385 AD) during the 11th century,[4][5][6][7] while Christianity came to Nigeria in the 15th century through Augustinian and Capuchin monks from Portugal to the Kingdom of Warri.[8] The Songhai Empire also occupied part of the region.[9] From the 15th century, European slave traders arrived in the region to purchase enslaved Africans as part of the Atlantic slave trade, which started in the region of modern-day Nigeria; the first Nigerian port used by European slave traders was Badagry, a coastal harbour.[10][11] Local merchants provided them with slaves, escalating conflicts among the ethnic groups in the region and disrupting older trade patterns through the Trans-Saharan route.[12]

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||

| History of Nigeria | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||

| By state | ||||||||||||||||||

| See also | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Lagos was occupied by British forces in 1851 and formally annexed by Britain in the year 1865.[13] Nigeria became a British protectorate in 1901. The period of British rule lasted until 1960 when an independence movement led to the country being granted independence.[14] Nigeria first became a republic in 1963, but succumbed to military rule after a bloody coup d'état in 1966. A separatist movement later formed the Republic of Biafra in 1967, leading to the three-year Nigerian Civil War.[15] Nigeria became a republic again after a new constitution was written in 1979. However, the republic was short-lived, as the military seized power again in 1983 and later ruled for ten years. A new republic was planned to be established in 1993 but was aborted by General Sani Abacha. Abacha died in 1998 and a fourth republic was later established the following year, 1999, which ended three decades of intermittent military rule.

Prehistory

Early Stone Age

Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (Middle Pleistocene).[16]

Middle Stone Age

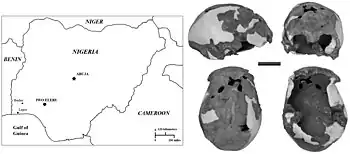

Middle Stone Age West Africans likely dwelled continuously in West Africa between MIS 4 and MIS 2, and likely were not present in West Africa before MIS 5.[17] Amid MIS 5, Middle Stone Age West Africans may have migrated across the West Sudanian savanna and continued to reside in the region (e.g., West Sudanian savanna, West African Sahel).[17] In the Late Pleistocene, Middle Stone Age West Africans began to dwell along parts of the forest and coastal region of West Africa (e.g., Tiemassas, Senegal).[17] More specifically, by at least 61,000 BP, Middle Stone Age West Africans may have begun to migrate south of the West Sudanian savanna, and, by at least 25,000 BP, may have begun to dwell near the coast of West Africa.[17] Amid aridification in MIS 5 and regional change of climate in MIS 4, in the Sahara and the Sahel, Aterians may have migrated southward into West Africa (e.g., Baie du Levrier, Mauritania; Tiemassas, Senegal; Lower Senegal River Valley).[17] Iwo Eleru people persisted at Iwo Eleru, in Nigeria, as late as 13,000 BP.[18]

Later Stone Age

Earlier than 32,000 BP,[19] or by 30,000 BP,[20][21] Late Stone Age West African hunter-gatherers were dwelling in the forests of western Central Africa[21][20] (e.g., earlier than 32,000 BP at de Maret in Shum Laka,[19] 12,000 BP at Mbi Crater).[21] An excessively dry Ogolian period occurred, spanning from 20,000 BP to 12,000 BP.[19] By 15,000 BP, the number of settlements made by Middle Stone Age West Africans decreased as there was an increase in humid conditions, expansion of the West African forest, and increase in the number of settlements made by Late Stone Age West African hunter-gatherers.[20] Macrolith-using late Middle Stone Age peoples (e.g., the possibly archaic human admixed[22] or late-persisting early modern human[18][23] Iwo Eleru fossils of the late Middle Stone Age), who dwelled in Central Africa, to western Central Africa, to West Africa, were displaced by microlith-using Late Stone Age Africans (e.g., non-archaic human admixed Late Stone Age Shum Laka fossils dated between 7000 BP and 3000 BP) as they migrated from Central Africa, to western Central Africa, into West Africa.[22] Between 16,000 BP and 12,000 BP, Late Stone Age West Africans began dwelling in the eastern and central forested regions (e.g., Ghana, Ivory Coast, Nigeria;[20] between 18,000 BP and 13,000 BP at Temet West and Asokrochona in the southern region of Ghana, 13,050 ± 230 BP at Bingerville in the southern region of Ivory Coast, 11,200 ± 200 BP at Iwo Eleru in Nigeria)[21] of West Africa.[20] After having persisted as late as 1000 BP,[24] or some period of time after 1500 CE,[25] remaining West African hunter-gatherers, many of whom dwelt in the forest-savanna region, were ultimately acculturated and admixed into the larger groups of West African agriculturalists, akin to the migratory Bantu-speaking agriculturalists and their encounters with Central African hunter-gatherers.[24] In the northeastern region of Nigeria, Jalaa, a language isolate, may be a descendant language from the original set(s) of languages spoken by West African hunter-gatherers.[24]

The Dufuna canoe, a dugout canoe found in northern Nigeria has been dated to around 6556-6388 BCE and 6164-6005 BCE,[26] making it the oldest known boat in Africa, and (after the Pesse canoe), the second oldest worldwide.[26][27]

Iron Age

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in West Africa, Central Africa, and East Africa; consequently, as these origin centers are located within inner Africa, these archaeometallurgical developments are thus native African technologies.[28] Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[29][30] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[30][31] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE.[32][33] More recently, Bandama and Babalola (2023) have indicated that iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BCE – 2458 BCE at Lejja, in Nigeria, 2136 BCE – 1921 BCE at Obui, in Central Africa Republic, 1895 BCE – 1370 BCE at Tchire Ouma 147, in Niger, and 1297 BCE – 1051 BCE at Dekpassanware, in Togo.[28]

Nok culture

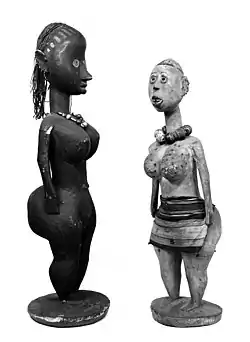

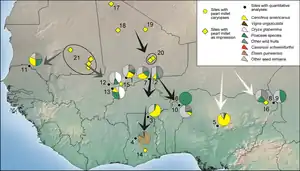

The Nok peoples and the Gajiganna peoples may have migrated from the Central Sahara, along with pearl millet and pottery, diverged prior to arriving in the northern region of Nigeria, and thus, settled in their respective locations in the region of Gajiganna and Nok.[34] Nok culture may have emerged in 1500 cal BCE and continued to persist until 1 cal BCE.[34] Nok people may have developed terracotta sculptures, through large-scale economic production,[35] as part of a complex funerary culture[36] that may have included practices such as feasting.[34] The earliest Nok terracotta sculptures may have developed in 900 BCE.[34] Some Nok terracotta sculptures portray figures wielding slingshots, as well as bows and arrows, which may be indicative of Nok people engaging in the hunting, or trapping, of undomesticated animals.[37] A Nok sculpture portrays two individuals, along with their goods, in a dugout canoe.[37] Both of the anthropomorphic figures in the watercraft are paddling.[38] The Nok terracotta depiction of a dugout canoe may indicate that Nok people used dugout canoes to transport cargo, along tributaries (e.g., Gurara River) of the Niger River, and exchanged them in a regional trade network.[38] The Nok terracotta depiction of a figure with a seashell on its head may indicate that the span of these riverine trade routes may have extended to the Atlantic coast.[38] In the maritime history of Africa, there is the earlier Dufuna canoe, which was constructed approximately 8000 years ago in the northern region of Nigeria; as the second earliest form of water vessel known in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Nok terracotta depiction of a dugout canoe was created in the central region of Nigeria during the first millennium BCE.[38] Latter artistic traditions of West Africa – Bura of Niger (3rd century CE – 10th century CE), Koma of Ghana (7th century CE – 15th century CE), Igbo-Ukwu of Nigeria (9th century CE – 10th century CE), Jenne-Jeno of Mali (11th century CE – 12th century CE), and Ile Ife of Nigeria (11th century CE – 15th century CE) – may have been shaped by the earlier West African clay terracotta tradition of the Nok culture.[39] Mountaintops are where the majority of Nok settlement sites are found.[40] At the settlement site of Kochio, the edge of a cellar of a settlement wall was chiseled from a granite foundation.[40] Additionally, a megalithic stone fence was constructed around the enclosed settlement site of Kochio.[40] Also, a circular stone foundation of a hut was discovered in Puntun Dutse.[41] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE.[32][33] As each share cultural and artistic similarity with the Nok culture found in Nok, Sokoto, and Katsina, the Niger-Congo-speaking Yoruba, Jukun, or Dakakari peoples may be descendants of the Nok peoples.[42] Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba Ife Empire and the Bini kingdom of Benin may also be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[43]

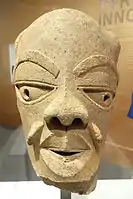

Nok seated figure; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; terracotta; 38 cm (1 ft. 3 in.); Musée du quai Branly (Paris). In this Nok work, the head is dramatically larger than the body supporting it, yet the figure possesses elegant details and a powerful focus. The neat protrusion from the chin represents a beard. Necklaces form a cone around the neck and keep the focus on the face.

Nok seated figure; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; terracotta; 38 cm (1 ft. 3 in.); Musée du quai Branly (Paris). In this Nok work, the head is dramatically larger than the body supporting it, yet the figure possesses elegant details and a powerful focus. The neat protrusion from the chin represents a beard. Necklaces form a cone around the neck and keep the focus on the face..JPG.webp) Nok artwork; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; length: 50 cm (19.6 in.), height: 54 cm (21.2 in.), width: 50 cm (19.6 in.); terracotta; Musée du quai Branly. As in most African art styles, the Nok style focuses mainly on people, rarely on animals. All of the Nok statues are very stylized and similar in that they have arched eyebrows with triangular eyes and perforated pupils.

Nok artwork; 5th century BC – 5th century AD; length: 50 cm (19.6 in.), height: 54 cm (21.2 in.), width: 50 cm (19.6 in.); terracotta; Musée du quai Branly. As in most African art styles, the Nok style focuses mainly on people, rarely on animals. All of the Nok statues are very stylized and similar in that they have arched eyebrows with triangular eyes and perforated pupils. Nok male head; 550-50 BC; terracotta; Brooklyn Museum (New York City, USA). The mouth of this head is slightly open. It might suggest speech and that the figure has something to tell us. This is a figure that seems to be in the midst of a conversation. The eyes and the eyebrows suggest an inner calm or an inner serenity.

Nok male head; 550-50 BC; terracotta; Brooklyn Museum (New York City, USA). The mouth of this head is slightly open. It might suggest speech and that the figure has something to tell us. This is a figure that seems to be in the midst of a conversation. The eyes and the eyebrows suggest an inner calm or an inner serenity. Nok male figure; terracotta; Detroit Institute of Art (Michigan, USA)

Nok male figure; terracotta; Detroit Institute of Art (Michigan, USA)

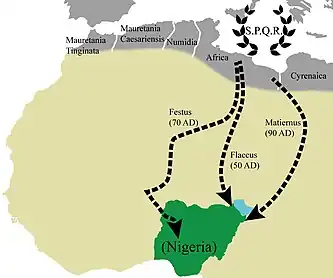

Roman expeditions to Nigeria (1st century AD)

Between 50 AD and 90 AD, Roman explorers undertook three expeditions to the area of present-day Nigeria. The reports of these expeditions confirm, among other things, the geologically already established extent of Lake Chad at that time and thus its drastic shrinkage in the past 2,000 years.

The expeditions were supported by legionaries and served mainly commercial purposes.[44]

One of the main goals of the explorations was the search for and extraction of gold, which was to be transported back to the Roman provinces on the Mediterranean coast by land with the help of camels.[45]

The Romans had at their disposal the memoirs of the ancient Carthaginian explorer Hanno the Navigator.[46] However, it is not known to what extent they were read, believed or found interesting by the Romans.

Septimius Flaccus and Julius Maternus reached the "Lake of Hippos" (as Lake Chad was called by Ptolemy). They came from the coast of Tripolitania and moved near the Tibesti Mountains. Both undertook their expeditions through the territory of the Garamantes and were able to leave a small garrison at the "Lake of Hippos and Rhinos" after a three-month journey through desert areas.

The three Roman explorations/expeditions in Nigeria were:

- The Flaccus expedition: Ptolemy wrote that Septimius Flaccus carried out his expedition in 50 AD (at the time of Emperor Claudius) to take revenge on the nomadic raiders who had attacked Leptis Magna and reached Sebha and the Aozou area.[47] He then reached the Bahr Erguig, Chari and Logone rivers in the Lake Chad area, which was called the "land of the Ethiopians" (or black men) and called Agisymba.

- The Matiernus expedition: Ptolemy wrote that Julius Maternus (or Matiernus) undertook a mainly commercial expedition around 90 AD (the time of Domitian). From the Gulf of Sirte, he reached the oasis of Cufra and the oasis of Archei, and then - after a four-month journey with the king of the Garamantes - arrived at the rivers Bahr Salamat and Bahr Aouk near what is now the Central African Republic in a region then called Agisymba. He returned to Rome with a rhinoceros with two horns, which was exhibited in the Colosseum.[48] According to Raphael Joorde, Maternus was a diplomat who explored the area south of the Tibesti Mountains with the king of Garamantes while that king was conducting a military campaign against rebellious subjects, or a "raid."[49]

- According to historians such as Susan Raven,[50] there was another Roman expedition to Central Africa: that of Valerius Festus, which may have reached northwestern Nigeria thanks to the Niger River.[51] Pliny wrote that in 70 AD. (in the time of Vespasian), a legatus legionis or commander of Legio III Augusta named Festus undertook an expedition in the direction of the Niger River. Festus went to the eastern Hoggar Mountains and advanced via the Aïr Mountains to the plain of Gadoufaoua. Festus eventually arrived in the area where Timbuktu is located today. Some scholars such as Fage[52] believe that he only reached the Ghat region in southern Libya, near the border with southern Algeria and Niger. However, it is possible that some of his legionnaires may have reached as far as the Niger River, and reached as far as the forests on the equator, navigating the river to its mouth in what is now Nigeria. Something similar may have happened during the exploration of the Nile under Emperor Nero.

Roman coins have been found in Nigeria. However, it is likely that all these coins were introduced at a much later date and there was not direct Roman traffic this far down the west coast. The coins are the only ancient European items found in Central Africa.[53]

Early states before 1500

The early independent kingdoms and states that make up present-day state of Nigeria are (in alphabetical order): Benin Kingdom, Borgu Kingdom, Fulani Empire, Hausa Kingdoms, Kanem Bornu Empire, Kwararafa Kingdom, Ibibio Kingdom, Nri Kingdom, Nupe Kingdom, Oyo Empire, Songhai Empire, Warri Kingdom, Ile Ife Kingdom, and Yagba East Kingdom.

Oyo and Benin

During the 15th century, Oyo and Benin surpassed Ife as political and economic powers, although Ife preserved its status as a religious center. Respect for the priestly functions of the oni of Ife was a crucial factor in the evolution of Yoruba culture. The Ife model of government was adapted at Oyo, where a member of its ruling dynasty controlled several smaller city-states. A state council (the Oyo Mesi) named the Alaafin (king) and acted as a check on his authority. Their capital city was situated about 100 km north of present-day Oyo. Unlike the forest-bound Yoruba kingdoms, Oyo was in the savanna and drew its military strength from its cavalry forces, which established hegemony over the adjacent Nupe and the Borgu kingdoms and thereby developed trade routes farther to the north.

The Benin Empire (1440–1897; called Bini by locals) was a pre-colonial African state in what is now modern Nigeria. It should not be confused with the modern-day country called Benin, formerly called Dahomey.[54]

The Igala are an ethnic group of Nigeria. Their homeland, the former Igala Kingdom, is an approximately triangular area of about 14,000 km2 (5,400 sq mi) in the angle formed by the Benue and Niger rivers. The area was formerly the Igala Division of Kabba province, and is now part of Kogi State. The capital is Idah in Kogi state. Igala people are majorly found in Kogi state. They can be found in Idah, Igalamela/Odolu, Ajaka, Ofu, Olamaboro, Dekina, Bassa, Ankpa, omala, Lokoja, Ibaji, Ajaokuta, Lokoja and kotonkarfe Local government all in Kogi state. Other states where Igalas can be found are Anambra, Delta and Benue states. The royal stool of Olu of warri was founded by an Igala prince.

Savanna states

During the 16th century, the Songhai Empire reached its peak, stretching from the Senegal and Gambia rivers and incorporating part of Hausaland in the east. Concurrently the Saifawa Dynasty of Borno conquered Kanem and extended control west to Hausa cities not under Songhai authority. Largely because of Songhai's influence, there was a blossoming of Islamic learning and culture. Songhai collapsed in 1591 when a Moroccan army conquered Gao and Timbuktu. Morocco was unable to control the empire and the various provinces, including the Hausa states, became independent. The collapse undermined Songhai's hegemony over the Hausa states and abruptly altered the course of regional history.

Borno reached its pinnacle under mai Idris Aloma (ca. 1569–1600) during whose reign Kanem was reconquered. The destruction of Songhai left Borno uncontested and until the 18th-century Borno dominated northern Nigeria. Despite Borno's hegemony the Hausa states continued to wrestle for ascendancy. Gradually Borno's position weakened; its inability to check political rivalries between competing Hausa cities was one example of this decline. Another factor was the military threat of the Tuareg centred at Agades who penetrated the northern districts of Borno. The major cause of Borno's decline was a severe drought that struck the Sahel and savanna from in the middle of the 18th century. As a consequence, Borno lost many northern territories to the Tuareg whose mobility allowed them to endure the famine more effectively. Borno regained some of its former might in the succeeding decades, but another drought occurred in the 1790s, again weakening the state.

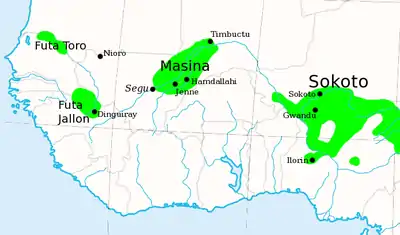

Ecological and political instability provided the background for the jihad of Usman dan Fodio. The military rivalries of the Hausa states strained the region's economic resources at a time when drought and famine undermined farmers and herders. Many Fulani moved into Hausaland and Borno, and their arrival increased tensions because they had no loyalty to the political authorities, who saw them as a source of increased taxation. By the end of the 18th century, some Muslim ulema began articulating the grievances of the common people. Efforts to eliminate or control these religious leaders only heightened the tensions, setting the stage for jihad.[55]

According to the Encyclopedia of African History, "It is estimated that by the 1890s the largest slave population of the world, about 2 million people, was concentrated in the territories of the Sokoto Caliphate. The use of slave labour was extensive, especially in agriculture."[56]

Northern kingdoms of the Sahel

Trade is the key to the emergence of organized communities in the sahelian portions of Nigeria. Prehistoric inhabitants adjusting to the encroaching desert were widely scattered by the third millennium BC, when the desiccation of the Sahara began. Trans-Saharan trade routes linked the western Sudan with the Mediterranean since the time of Carthage and with the Upper Nile from a much earlier date, establishing avenues of communication and cultural influence that remained open until the end of the 19th century. By these same routes, Islam made its way south into West Africa after the 9th century.

By then a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched into western and central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and Kanem, which were not within the boundaries of modern Nigeria but which influenced the history of the Nigerian savanna. Ghana declined in the 11th century but was succeeded by the Mali Empire which consolidated much of western Sudan in the 13th century.

Following the breakup of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali (1464–1492) founded the Songhai Empire in the region of middle Niger and western Sudan and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sonni Ali seized Timbuktu in 1468 and Djenné in 1473, building his regime on trade revenues and the cooperation of Muslim merchants. His successor Askia Muhammad Ture (1493–1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought Muslim scholars, including al-Maghili (d.1504), the founder of an important tradition of Sudanic African Muslim scholarship, to Gao.[55]

Although these western empires had little political influence on the Nigerian savanna before 1500 they had a strong cultural and economic impact that became more pronounced in the 16th century, especially because these states became associated with the spread of Islam and trade. Throughout the 16th-century much of northern Nigeria paid homage to Songhai in the west or to Borno, a rival empire in the east.

The Golden Age

During the 14th and 16th centuries, the demand for gold increased due to European and Islamic states wanting to change their currencies to gold. This led to an increase in trans-Saharan Trade.[57]

Kanem–Bornu Empire

Borno's history is closely associated with Kanem, which had achieved imperial status in the Lake Chad basin by the 13th century. Kanem expanded westward to include the area that became Borno. The mai (king) of Kanem and his court accepted Islam in the 11th century, as the western empires also had done. Islam was used to reinforce the political and social structures of the state although many established customs were maintained. Women, for example, continued to exercise considerable political influence.[58]

The mai employed his mounted bodyguard and an inchoate army of nobles to extend Kanem's authority into Borno. By tradition, the territory was conferred on the heir to the throne to govern during his apprenticeship. In the 14th century, however, dynastic conflict forced the then-ruling group and its followers to relocate in Borno, as a result the Kanuri emerged as an ethnic group in the late 14th and 15th centuries. The civil war that disrupted Kanem in the second half of the 14th century resulted in the independence of Borno.[58]

Borno's prosperity depended on the trans-Sudanic slave trade and the desert trade in salt and livestock. The need to protect its commercial interests compelled Borno to intervene in Kanem, which continued to be a theatre of war throughout the 15th century and into the 16th century. Despite its relative political weakness in this period, Borno's court and mosques under the patronage of a line of scholarly kings earned fame as centres of Islamic culture and learning.[59]

Hausa Kingdoms

The Hausa Kingdoms were a collection of states started by the Hausa people, situated between the Niger River and Lake Chad. Their history is reflected in the Bayajidda legend,[60] which describes the adventures of the Baghdadi hero Bayajidda culminating in the killing of the snake (Sarki) in the well of Daura (Kusugu) and the marriage with the local queen magajiya Daurama. While the hero had a child with the queen, Bawo, and another child with the queen's maid-servant, Karbagari.[61][62] Today the Hausa people now reside in the Northern part of Nigeria.[63]

Sarki mythology

According to the Bayajidda legend, the Hausa states were founded by the sons of Bayajidda, a prince whose origin differs by tradition, but official canon records him as the person who married the last Kabara of Daura and heralded the end of the matriarchal monarchs that had erstwhile ruled the Hausa people.[60] Contemporary historical scholarship views this legend as an allegory similar to many in that region of Africa that probably referenced a major event, such as a shift in ruling dynasties.

Banza Bakwai

According to the Bayajidda legend, the Banza Bakwai states were founded by the seven sons of Karbagari ("Town-seizer"), the unique son of Bayajidda and the slave-maid, Bagwariya.[64] They are called the Banza Bakwai meaning Bastard or Bogus Seven on account of their ancestress' slave status.[64]

Hausa Bakwai

The Hausa Kingdoms began as seven states founded according to the Bayajidda legend by the six sons of Bawo, the unique son of the hero and the queen Magajiya Daurama in addition to the hero's son, Biram or Ibrahim, of an earlier marriage.[64] The states included only kingdoms inhabited by Hausa-speakers:

Since the beginning of Hausa history, the seven states of Hausaland divided up production and labor activities in accordance with their location and natural resources. Kano and Rano were known as the "Chiefs of Indigo." Cotton grew readily in the great plains of these states, and they became the primary producers of cloth, weaving and dying it before sending it off in caravans to the other states within Hausaland and to extensive regions beyond. Biram was the original seat of government, while Zaria supplied labor and was known as the "Chief of Slaves." Katsina and Daura were the "Chiefs of the Market," as their geographical location accorded them direct access to the caravans coming across the desert from the north. Gobir, located in the west, was the "Chief of War" and was mainly responsible for protecting the empire from the invasive Kingdoms of Ghana and Songhai.[65] Islam arrived at Hausaland along the caravan routes. The famous Kano Chronicle records the conversion of Kano's ruling dynasty by clerics from Mali, demonstrating that the imperial influence of Mali extended far to the east. Acceptance of Islam was gradual and was often nominal in the countryside where folk religion continued to exert a strong influence. Nonetheless, Kano and Katsina, with their famous mosques and schools, came to participate fully in the cultural and intellectual life of the Islamic world.[66] The Fulani began to enter the Hausa country in the 13th century and by the 15th century, they were tending cattle, sheep, and goats in Borno as well. The Fulani came from the Senegal River valley, where their ancestors had developed a method of livestock management based on transhumance. Gradually they moved eastward, first into the centers of the Mali and Songhai empires and eventually into Hausaland and Borno. Some Fulbe converted to Islam as early as the 11th century and settled among the Hausa, from whom they became racially indistinguishable. There they constituted a devoutly religious, educated elite who made themselves indispensable to the Hausa kings as government advisers, Islamic judges, and teachers.[31]

Zenith

The Hausa Kingdoms were first mentioned by Ya'qubi in the 9th century and they were by the 15th-century vibrant trading centers competing with Kanem–Bornu and the Mali Empire. The primary exports were slaves, leather, gold, cloth, salt, kola nuts, and henna. At various moments in their history, the Hausa managed to establish central control over their states, but such unity has always proven short. In the 11th-century, the conquests initiated by Gijimasu of Kano culminated in the birth of the first united Hausa Nation under Queen Amina, the Sultana of Zazzau but severe rivalries between the states led to periods of domination by major powers like the Songhai, Kanem and the Fulani.[67]

Fall

Despite relatively constant growth, the Hausa states were vulnerable to aggression and, although the vast majority of its inhabitants were Muslim by the 16th century, they were attacked by Fulani jihadists from 1804 to 1808. In 1808 the Hausa Nation was finally conquered by Usman dan Fodio and incorporated into the Hausa-Fulani Sokoto Caliphate.[68]

Yoruba

Historically, the Yoruba people have been the dominant group on the west bank of the Niger. Their nearest linguistic relatives are the Igala who live on the opposite side of the Niger's divergence from the Benue, and from whom they are believed to have split about 2,000 years ago. The Yoruba were organized in mostly patrilineal groups that occupied village communities and subsisted on agriculture. From approximately the 8th century, adjacent village compounds called ilé coalesced into numerous territorial city-states in which clan loyalties became subordinate to dynastic chieftains.[69] Urbanisation was accompanied by high levels of artistic achievement, particularly in terracotta and ivory sculpture and in the sophisticated metal casting produced at Ife.

The Yoruba are especially known for the Oyo Empire that dominated the region. The Oyo Empire held supremacy over other Yoruba nations like the Egba Kingdom, Awori Kingdom, and the Egbado. In its prime, they also dominated the Kingdom of Dahomey (now located in the modern day Republic of Benin).[70]

The Yoruba pay tribute to a pantheon composed of a Supreme Deity, Olorun and the Orisha.[71] The Olorun is now called God in the Yoruba language. There are 400 deities called Orisha who perform various tasks.[72] According to the Yoruba, Oduduwa is regarded as the ancestor of the Yoruba kings. According to one of the various myths about him, he founded Ife and dispatched his sons and daughters to establish similar kingdoms in other parts of what is today known as Yorubaland. The Yorubaland now consists of different tribes from different states which are located in the Southwestern part of the country, states like Lagos State, Oyo State, Ondo State, Osun State, Ekiti State and Ogun State, among others.[73]

Igbo Kingdom

Nri Kingdom

The Kingdom of Nri is considered to be the foundation of Igbo culture and the oldest Kingdom in Nigeria.[74] Nri and Aguleri, where the Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umueri clan, who trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure, Eri.[75] Eri's origins are unclear, though he has been described as a "sky being" sent by Chukwu (God).[75][76] He has been characterized as having first given societal order to the people of Anambra.[76]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Nri hegemony in Igboland may go back as far as the 9th century,[77] and royal burials have been unearthed dating to at least the 10th century. Eri, the god-like founder of Nri, is believed to have settled in the region around 948 with other related Igbo cultures following in the 13th century.[78] The first Eze Nri (King of Nri), Ìfikuánim, followed directly after him. According to Igbo oral tradition, his reign started in 1043.[79] At least one historian puts Ìfikuánim's reign much later, around 1225.[80]

Each king traces his origin back to the founding ancestor, Eri. Each king is a ritual reproduction of Eri. The initiation rite of a new king shows that the ritual process of becoming Ezenri (Nri priest-king) follows closely the path traced by the hero in establishing the Nri kingdom.

— E. Elochukwu Uzukwu[76]

Nri and Aguleri and part of the Umueri clan, a cluster of Igbo village groups which traces its origins to a sky being called Eri and significantly, includes (from the viewpoint of its Igbo members) the neighbouring kingdom of Igala.

— Elizabeth Allo Isichei[81]

The Kingdom of Nri was a religio-polity, a sort of theocratic state, that developed in the central heartland of the Igbo region.[78] The Nri had a taboo symbolic code with six types. These included human (such as the birth of twins),[82] animal (such as killing or eating of pythons),[83] object, temporal, behavioral, speech and place taboos.[84] The rules regarding these taboos were used to educate and govern Nri's subjects. This meant that, while certain Igbo may have lived under different formal administrations, all followers of the Igbo religion had to abide by the rules of the faith and obey its representative on earth, the Eze Nri.[83][84]

Decline of Nri kingdom

With the decline of Nri kingdom in the 15th to 17th centuries, several states once under their influence, became powerful economic oracular oligarchies and large commercial states that dominated Igboland. The neighboring Awka city-state rose in power as a result of their powerful Agbala oracle and metalworking expertise. The Onitsha Kingdom, which was originally inhabited by Igbos from east of the Niger, was founded in the 16th century by migrants from Anioma (Western Igboland). Later groups like the Igala traders from the hinterland settled in Onitsha in the 18th century. Kingdoms west of the River Niger like Aboh (Abo), which was significantly populated by Igbos among other tribes, dominated trade along the lower River Niger area from the 17th century until European explorations into the Niger delta. The Umunoha state in the Owerri area used the Igwe ka Ala oracle at their advantage. However, the Cross River Igbo state like the Aro had the greatest influence in Igboland and adjacent areas after the decline of Nri.[85][86]

The Arochukwu kingdom emerged after the Aro-Ibibio Wars from 1630 to 1720, and went on to form the Aro Confederacy which economically dominated Eastern Nigerian hinterland. The source of the Aro Confederacy's economic dominance was based on the judicial oracle of Ibini Ukpabi ("Long Juju") and their military forces which included powerful allies such as Ohafia, Abam, Ezza, and other related neighboring states. The Abiriba and Aro are Brothers whose migration is traced to the Ekpa Kingdom, East of Cross River, their exact take of location was at Ekpa (Mkpa) east of the Cross River. They crossed the river to Urupkam (Usukpam) west of the Cross River and founded two settlements: Ena Uda and Ena Ofia in present-day Erai. Aro and Abiriba cooperated to become a powerful economic force.[87]

Igbo gods, like those of the Yoruba, were numerous, but their relationship to one another and human beings was essentially egalitarian, reflecting Igbo society as a whole. A number of oracles and local cults attracted devotees while the central deity, the earth mother and fertility figure Ala, was venerated at shrines throughout Igboland.

The weakness of a popular theory that Igbos were stateless rests on the paucity of historical evidence of pre-colonial Igbo society. There is a huge gap between the archaeological finds of Igbo Ukwu, which reveal a rich material culture in the heart of the Igbo region in the 8th century, and the oral traditions of the 20th century. Benin exercised considerable influence on the western Igbo, who adopted many of the political structures familiar to the Yoruba-Benin region, but Asaba and its immediate neighbours, such as Ibusa, Ogwashi-Ukwu, Okpanam, Issele-Azagba and Issele-Ukwu, were much closer to the Kingdom of Nri. Ofega was the queen for the Onitsha Igbo.

Akwa Akpa

The modern city of Calabar was founded in 1786 by Efik families who had left Creek Town, farther up the Calabar river, settling on the east bank in a position where they were able to dominate traffic with European vessels that anchored in the river, and soon becoming the most powerful in the region extending from now Calabar down to Bakkasi in the East and Oron Nation in the West.[88] Akwa Akpa (named Calabar by the Spanish) became a center of the Atlantic slave trade, where African slaves were sold in exchange for European manufactured goods.[89] Igbo people formed the majority of enslaved Africans which were sold as slaves from Calabar, despite forming a minority among the ethnic groups in the region.[90] From 1725 until 1750, roughly 17,000 enslaved Africans were sold from Calabar to European slave traders; from 1772 to 1775, the number soared to over 62,000.[91]

With the suppression of the slave trade,[92] palm oil and palm kernels became the main exports. The chiefs of Akwa Akpa placed themselves under British protection in 1884.[93] From 1884 until 1906 Old Calabar was the headquarters of the Niger Coast Protectorate, after which Lagos became the main center.[93] Now called Calabar, the city remained an important port shipping ivory, timber, beeswax, and palm produce until 1916, when the railway terminus was opened at Port Harcourt, 145 km to the west.[94]

A British sphere of influence

.svg.png.webp)

Following the Napoleonic Wars, the British expanded trade with the Nigerian interior. In 1885, British claims to a West African sphere of influence received international recognition; and in the following year, the Royal Niger Company was chartered under the leadership of Sir George Taubman Goldie. On the 31st of December 1899 the charter for the Royal Niger Company was revoked by the British government, and the sum of £865,000 was paid to the company as compensation. The entire territory of the Royal Niger Company came into the hands of the British government.[95] On 1 January 1900, the British Empire created the Southern Nigeria Protectorate and the Northern Nigeria Protectorate.

In 1914, the area was formally united as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. Administratively, Nigeria remained divided into the Northern and Southern Provinces and Lagos Colony.[96] Western education and the development of a modern economy proceeded more rapidly in the south than in the north, with consequences felt in Nigeria's political life ever since. Following World War II, in response to the growth of Nigerian nationalism and demands for independence, successive constitutions legislated by the British government moved Nigeria toward self-government on a representative and increasingly federal basis. On 1 October 1954, the colony became the autonomous Federation of Nigeria. By the middle of the 20th century, the great wave for independence was sweeping across Africa. On 27 October 1958 Britain agreed that Nigeria would become an independent state on 1 October 1960.[97]

Independence

The Federation of Nigeria was granted full independence on 1 October 1960 under a constitution that provided for a parliamentary government and a substantial measure of self-government for the country's three regions. From 1959 to 1960, Jaja Wachuku was the First Nigerian Speaker of the Nigerian Parliament, also called the "House of Representatives." Jaja Wachuku replaced Sir Frederick Metcalfe of Britain. Notably, as First Speaker of the House, Jaja Wachuku received Nigeria's Instrument of Independence, also known as Freedom Charter, on 1 October 1960, from Princess Alexandra of Kent, the Queen's representative at the Nigerian independence ceremonies. Queen Elizabeth II was monarch of Nigeria and head of state, and Nigeria was a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations. The Federal government was given exclusive powers in defence, foreign relations, and commercial and fiscal policy. The monarch of Nigeria was still head of state but legislative power was vested in a bicameral parliament, executive power in a prime minister and cabinet, and judicial authority in a Federal Supreme Court. Political parties, however, tended to reflect the makeup of the three main ethnic groups. The Northern People's Congress (NPC) represented conservative, Muslim, largely Hausa and Fulani interests that dominated the northern region of the country, consisting of three-quarters of the land area and more than half the population of Nigeria. Thus the North dominated the federation government from the beginning of independence. In the 1959 elections held in preparation for independence, the NPC captured 134 seats in the 312-seat parliament.[98]

Capturing 89 seats in the federal parliament was the second-largest party in the newly independent country the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC). The NCNC represented the interests of the Igbo- and Christian-dominated people of the Eastern Region of Nigeria.[98] and the Action Group (AG) was a left-leaning party that represented the interests of the Yoruba people in the West. In the 1959 elections, the AG obtained 73 seats.[98]

The first post-independence national government was formed by a conservative alliance of the NCNC and the NPC. Upon independence, it was widely expected that Ahmadu Bello the Sardauna of Sokoto, the undisputed strong man in Nigeria[99] who controlled the North, would become Prime Minister of the new Federation Government. However, Bello chose to remain as premier of the North and as party boss of the NPC, selected Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, a Hausa, to become Nigeria's first Prime Minister.

The Yoruba-dominated AG became the opposition under its charismatic leader Chief Obafemi Awolowo. However, in 1962, a faction arose within the AG under the leadership of Ladoke Akintola who had been selected as premier of the West. The Akintola faction argued that the Yoruba peoples were losing their pre-eminent position in business in Nigeria to people of the Igbo tribe because the Igbo-dominated NCNC was part of the governing coalition and the AG was not.[98] The federal government Prime Minister, Balewa agreed with the Akintola faction and sought to have the AG join the government. The party leadership under Awolowo disagreed and replaced Akintola as premier of the West with one of their own supporters. However, when the Western Region parliament met to approve this change, Akintola supporters in the parliament started a riot in the chambers of the parliament.[100] Fighting between the members broke out. Chairs were thrown and one member grabbed the parliamentary Mace and wielded it like a weapon to attack the Speaker and other members. Eventually, the police with tear gas were required to quell the riot. In subsequent attempts to reconvene the Western parliament, similar disturbances broke out.[100] Unrest continued in the West and contributed to the Western Region's reputation for, violence, anarchy and rigged elections.[101] Federal Government Prime Minister Balewa declared martial law in the Western Region and arrested Awolowo and other members of his faction charged them with treason. Akintola was appointed to head a coalition government in the Western Region. Thus, the AG was reduced to an opposition role in their own stronghold.[100]

First Republic

In October 1963, Nigeria proclaimed itself the Federal Republic of Nigeria, and former Governor-General Nnamdi Azikiwe became the country's first President. From the outset, Nigeria's ethnic and religious tensions were magnified by the disparities in economic and educational development between the south and the north. The AG was manoeuvred out of control of the Western Region by the Federal Government and a new pro-government Yoruba party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), took over. Shortly afterwards the AG opposition leader, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, was imprisoned to be without foundation. The 1965 national election produced a major realignment of politics and a disputed result that set the country on the path to civil war.[102] The dominant northern NPC went into a conservative alliance with the new Yoruba NNDP, leaving the Igbo NCNC to coalesce with the remnants of the AG in a progressive alliance. In the vote, widespread electoral fraud was alleged and riots erupted in the Yoruba West where heartlands of the AG discovered they had apparently elected pro-government NNDP representatives.

First period of military rule

On 15 January 1966, a group of army officers (the Young Majors) mostly south-eastern Igbos, overthrew the NPC-NNDP government and assassinated the prime minister and the premiers of the northern and western regions. However, the bloody nature of the Young Majors coup caused another coup to be carried out by General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi. The Young Majors went into hiding. Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna fled to Kwame Nkrumah's Ghana where he was welcomed as a hero.[103] Some of the Young Majors were arrested and detained by the Ironsi government. Among the Igbo people of the Eastern Region, these detainees were heroes.[104] In the Northern Region, however, the Hausa and Fulani people demanded that the detainees be placed on trial for murder.[104]

The federal military government that assumed power under General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi was unable to quiet ethnic tensions on the issue or other issues. Additionally, the Ironsi government was unable to produce a constitution acceptable to all sections of the country. Most fateful for the Ironsi government was the decision to issue Decree No. 34 which sought to unify the nation.[105] Decree No. 34 sought to do away with the whole federal structure under which the Nigerian government had been organised since independence. Rioting broke out in the North.[106] The Ironsi government's efforts to abolish the federal structure and the renaming the country the Republic of Nigeria on 24 May 1966 raised tensions and led to another coup by largely northern officers in July 1966, which established the leadership of Major General Yakubu Gowon.[107] The name Federal Republic of Nigeria was restored on 31 August 1966. However, the subsequent massacre of thousands of Ibo in the north prompted hundreds of thousands of them to return to the south-east where increasingly strong Igbo secessionist sentiment emerged. In a move towards greater autonomy to minority ethnic groups, the military divided the four regions into 12 states. However, the Igbo rejected attempts at constitutional revisions and insisted on full autonomy for the east.

The Central Intelligence Agency commented in October 1966 in a CIA Intelligence Memorandum that:[108]

"Africa's most populous country (population estimated at 48 million) is in the throes of a highly complex internal crisis rooted in its artificial origin as a British dependency containing over 250 diverse and often antagonistic tribal groups. The present crisis started" with Nigerian independence in 1960, but the federated parliament hid "serious internal strains. It has been in an acute stage since last January when a military coup d'état destroyed the constitutional regime bequeathed by the British and upset the underlying tribal and regional power relationships. At stake now are the most fundamental questions which can be raised about a country, beginning with whether it will survive as a single viable entity.

The situation is uncertain, with Nigeria, ..is sliding downhill faster and faster, with less and less chance unity and stability. Unless present army leaders and contending tribal elements soon reach agreement on a new basis for the association and take some effective measures to halt a seriously deteriorating security situation, there will be increasing internal turmoil, possibly including civil war.

On 29 May 1967, Lt. Col. Emeka Ojukwu, the military governor of the eastern region who emerged as the leader of increasing Igbo secessionist sentiment, declared the independence of the eastern region as the Republic of Biafra on 30 May 1967.[109] The ensuing Nigerian Civil War resulted in an estimated 3.5 million deaths (mostly from starving children) before the war ended with Gowon's famous "No victor, no vanquished" speech in 1970.[110]

Following the civil war, the country turned to the task of economic development. The U.S. intelligence community concluded in November 1970 that "...The Nigerian Civil War ended with relatively little rancour. The Igbos were accepted as fellow citizens in many parts of Nigeria, but not in some areas of former Biafra where they were once dominant. Iboland is an overpopulated, economically depressed area where massive unemployment is likely to continue for many years.[111]

The U.S. analysts said that "...Nigeria is still very much a tribal society..." where local and tribal alliances count more than "national attachment. General Yakubu Gowon, head of the Federal Military Government (FMG) is the accepted national leader and his popularity has grown since the end of the war. The FMG is neither very efficient nor dynamic, but the recent announcement that it intends to retain power for six more years has generated little opposition so far. The Nigerian Army, vastly expanded during the war, is both the main support to the FMG and the chief threat to it. The troops are poorly trained and disciplined and some of the officers are turning to conspiracies and plotting. We think Gowon will have great difficulty in staying in office through the period which he said is necessary before the turnover of power to civilians. His sudden removal would dim the prospects for Nigerian stability."

"Nigeria's economy came through the war in better shape than expected." Problems exist with inflation, internal debt, and a huge military budget, competing with popular demands for government services. "The petroleum industry is expanding faster than expected and oil revenues will help defray military and social service expenditures... "Nigeria emerged from the war with a heightened sense of national pride mixed with an anti-foreign sentiment, and an intention to play a larger role in African and world affairs." British cultural influence is strong but its political influence is declining. The Soviet Union benefits from Nigerian appreciation of its help during the war, but is not trying for control. Nigerian relations with the US, cool during the war, are improving, but France may be seen as the future patron. "Nigeria is likely to take a more active role in funding liberation movements in southern Africa." Lagos, however, is not perceived as the "spiritual and bureaucratic capital of Africa"; Addis Ababa has that role...."

Foreign exchange earnings and government revenues increased spectacularly with the oil price rises of 1973–74. On July 29, 1975, Gen. Murtala Mohammed and a group of officers staged a bloodless coup, accusing Gen. Yakubu Gowon of corruption and delaying the promised return to civilian rule. General Mohammed replaced thousands of civil servants and announced a timetable for the resumption of civilian rule by 1 October 1979. He was assassinated on 13 February 1976 in an abortive coup and his chief of staff Lt. Gen. Olusegun Obasanjo became head of state.

Second Republic

A constituent assembly was elected in 1977 to draft a new constitution, which was published on 21 September 1978, when the ban on political activity was lifted. In 1979, five political parties competed in a series of elections in which Alhaji Shehu Shagari of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) was elected president.[112] All five parties won representation in the National Assembly.

During the 1950s prior to independence, oil was discovered off the coast of Nigeria. Almost immediately, the revenues from oil began to make Nigeria a wealthy nation. However, the spike in oil prices from $3 per barrel to $12 per barrel, following the Yom Kippur War in 1973 brought a sudden rush of money to Nigeria.[113] Another sudden rise in the price of oil in 1979 to $19 per barrel occurred as a result of the lead-up to the Iran–Iraq War.[113] All of this meant that by 1979, Nigeria was the sixth largest producer of oil in the world with revenues from oil of $24 billion per year.[112]

In 1982, the ruling National Party of Nigeria, a conservative alliance led by Shehu Shagari, had hoped to retain power through patronage and control over the Federal Election Commission. In August 1983, Shagari and the NPN were returned to power in a landslide with a majority of seats in the National Assembly and control of 12 state governments. But the elections were marred by violence and allegations of widespread voter fraud including missing returns, polling places failing to open, and obvious rigging of results. There was a fierce legal battle over the results, with the legitimacy of the victory at stake.[114][115]

On December 31, 1983, the military overthrew the Second Republic. Major General Muhammadu Buhari emerged as the leader of the Supreme Military Council (SMC), the country's new ruling body. The Buhari government was peacefully overthrown by the SMC's third-ranking member General Ibrahim Babangida in August 1985.[116] Babangida (IBB) cited the misuse of power, violations of human rights by key officers of the SMC, and the government's failure to deal with the country's deepening economic crisis as justifications for the takeover. During his first days in office, President Babangida moved to restore freedom of the press and to release political detainees being held without charge. As part of a 15-month economic emergency plan, he announced pay cuts for the military, police, civil servants, and the private sector. President Babangida demonstrated his intent to encourage public participation in decision-making by opening a national debate on proposed economic reform and recovery measures. The public response convinced Babangida of intense opposition to an economic recession.

The Abortive Third Republic

Head of State Babangida promised to return the country to civilian rule by 1990 which was later extended until January 1993. In early 1989 a constituent assembly completed a constitution and in the spring of 1989 political activity was again permitted. In October 1989 the government established two parties, the National Republican Convention (NRC) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP); other parties were not allowed to register.

In April 1990, mid-level officers attempted unsuccessfully to overthrow the government and 69 accused plotters were executed after secret trials before military tribunals. In December 1990 the first stage of partisan elections was held at the local government level. Despite the low turnout, there was no violence and both parties demonstrated strength in all regions of the country, with the SDP winning control of a majority of local government councils.

In December 1991, state legislative elections were held and Babangida decreed that previously banned politicians could contest in primaries scheduled for August. These were cancelled due to fraud and subsequent primaries scheduled for September also were cancelled. All announced candidates were disqualified from standing for president once a new election format was selected. The presidential election was finally held on 12 June 1993, with the inauguration of the new president scheduled to take place 27 August 1993, the eighth anniversary of President Babangida's coming to power.

In the historic 12 June 1993 presidential elections, which most observers deemed to be Nigeria's fairest, early returns indicated that wealthy Yoruba businessman M. K. O. Abiola won a decisive victory. However, on 23 June, Babangida, using several pending lawsuits as a pretence, annulled the election, throwing Nigeria into turmoil. More than 100 were killed in riots before Babangida agreed to hand power to an interim government on 26 August 1993. He later attempted to renege on this decision, but without popular and military support, he was forced to hand over to Ernest Shonekan, a prominent nonpartisan businessman. Shonekan was to rule until elections scheduled for February 1994. Although he had led Babangida's Transitional Council since 1993, Shonekan was unable to reverse Nigeria's economic problems or to defuse lingering political tension.

Sani Abacha

With the country sliding into chaos Defense Minister Sani Abacha assumed power and forced Shonekan's resignation on 17 November 1993.[117] Abacha dissolved all democratic institutions and replaced elected governors with military officers. Although promising restoration of civilian rule he refused to announce a transitional timetable until 1995. Following the annulment of the June 12 election, the United States and others imposed sanctions on Nigeria including travel restrictions on government officials and suspension of arms sales and military assistance. Additional sanctions were imposed as a result of Nigeria's failure to gain full certification for its counter-narcotics efforts.

Although Abacha was initially welcomed by many Nigerians, disenchantment grew rapidly. Opposition leaders formed the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), which campaigned to reconvene the Senate and other disbanded democratic institutions. On 11 June 1994 Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola declared himself president and went into hiding until his arrest on 23 June. In response, petroleum workers called a strike demanding that Abacha release Abiola and hand over power to him. Other unions joined the strike, bringing economic life around Lagos and the southwest to a standstill. After calling off a threatened strike in July the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) reconsidered a general strike in August after the government imposed conditions on Abiola's release. On 17 August 1994, the government dismissed the leadership of the NLC and the petroleum unions, placed the unions under appointed administrators, and arrested Frank Kokori and other labor leaders.

The government alleged in early 1995 that military officers and civilians were engaged in a coup plot. Security officers rounded up the accused, including former Head of State Obasanjo and his deputy, retired General Shehu Musa Yar'Adua. After a secret tribunal, most of the accused were convicted and several death sentences were handed down. In 1994 the government set up the Ogoni Civil Disturbances Special Tribunal to try Ogoni activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and others for their alleged roles in the killings of four Ogoni politicians. The tribunal sentenced Saro-Wiwa and eight others to death and they were executed on 10 November 1995.

On 1 October 1995, Abacha announced the timetable for a three-year transition to civilian rule. Only five political parties were approved by the regime and voter turnout for local elections in December 1997 was under 10%. On 20 December 1997, the government arrested General Oladipo Diya, ten officers, and eight civilians on charges of coup plotting. The accused were tried before a Gen Victor Malu military tribunal in which Diya and five others- Late Gen AK Adisa, Gen Tajudeen Olanrewaju, Late Col OO Akiyode, Major Seun Fadipe and a civilian Engr Bola Adebanjo were sentenced to death to die by firing squad. Abacha enforced authority through the federal security system which is accused of numerous human rights abuses, including infringements on freedom of speech, assembly, association, travel, and violence against women.

Abubakar's transition to civilian rule

Abacha died of heart failure on 8 June 1998 and was replaced by General Abdulsalami Abubakar. The military Provisional Ruling Council (PRC) under Abubakar commuted the sentences of those accused in the alleged coup during the Abacha regime and released almost all known civilian political detainees. Pending the promulgation of the constitution written in 1995, the government observed some provisions of the 1979 and 1989 constitutions. Neither Abacha nor Abubakar lifted the decree suspending the 1979 constitution, and the 1989 constitution was not implemented. The judiciary system continued to be hampered by corruption and lack of resources after Abacha's death. In an attempt to alleviate such problems Abubakar's government implemented a civil service pay raise and other reforms.

In August 1998, Abubakar appointed the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) to conduct elections for local government councils, state legislatures and governors, the national assembly, and president. The NEC successfully held elections on 5 December 1998, 9 January 1999, 20 February, and 27 February 1999, respectively. For local elections, nine parties were granted provisional registration with three fulfilling the requirements to contest the following elections. These parties were the People's Democratic Party (PDP), the All People's Party (APP), and the predominantly Yoruba Alliance for Democracy (AD). The former military head of state Olusegun Obasanjo, freed from prison by Abubakar, ran as a civilian candidate and won the presidential election. The PRC promulgated a new constitution based largely on the suspended 1979 constitution, before the 29 May 1999 inauguration of the new civilian president. The constitution includes provisions for a bicameral legislature, the National Assembly consisting of a 360-member House of Representatives and a 109-member Senate.

Fourth Republic

Main article: Fourth Nigerian Republic

The emergence of democracy in Nigeria in May 1999 ended 16 years of consecutive military rule. Olusegun Obasanjo inherited a country suffering economic stagnation and the deterioration of most democratic institutions. Obasanjo, a former general, was admired for his stand against the Abacha dictatorship, his record of returning the federal government to civilian rule in 1979, and his claim to represent all Nigerians regardless of religion.

The new president took over a country that faced many problems, including a dysfunctional bureaucracy, collapsed infrastructure, and a military that wanted a reward for returning quietly to the barracks. The President moved quickly and retired hundreds of military officers holding political positions, established a blue-ribbon panel to investigate human rights violations, released scores of persons held without charge, and rescinded numerous questionable licenses and contracts left by the previous regimes. The government also moved to recover millions of dollars in funds secreted to overseas accounts.[118]

Most civil society leaders and Nigerians witnessed marked improvements in human rights and freedom of the press under Obasanjo. As Nigeria works out representational democracy, conflicts persist between the Executive and Legislative branches over appropriations and other proposed legislation. A sign of federalism has been the growing visibility of state governors and the inherent friction between Abuja and the state capitals over resource allocation.[119]

Communal violence has plagued the Obasanjo government since its inception. In May 1999, violence erupted in Kaduna State over the succession of an Emir resulting in more than 100 deaths. In November 1999, the army destroyed the town of Odi, Bayelsa State and killed scores of civilians in retaliation for the murder of 12 policemen by a local gang. In Kaduna in February–May 2000, over 1,000 people died in rioting over the introduction of criminal Shar'ia in the State. Hundreds of ethnic Hausa were killed in reprisal attacks in south-eastern Nigeria. In September 2001, over 2,000 people were killed in inter-religious rioting in Jos. In October 2001, hundreds were killed and thousands displaced in communal violence that spread across the states of Benue, Taraba, and Nasarawa. On 1 October 2001, Obasanjo announced the formation of a National Security Commission to address the issue of communal violence. Obasanjo was reelected in 2003.

The new president faces the daunting task of rebuilding a petroleum-based economy, whose revenues have been squandered through corruption and mismanagement. Additionally, the Obasanjo administration must defuse longstanding ethnic and religious tensions if it hopes to build a foundation for economic growth and political stability. Currently, there is conflict in the Niger Delta over the environmental destruction caused by oil drilling and the ongoing poverty in the oil-rich region[120]..

A further major problem created by the oil industry is the drilling of pipelines by the local population in an attempt to drain off the petroleum for personal use or as a source of income. This often leads to major explosions and high death tolls.[121] Particularly notable disasters in this area have been: 1) October 1998, Jesse, 1100 deaths, 2) July 2000, Jesse, 250 deaths, 3) September 2004, near Lagos, 60 deaths, 4) May 2006, Ilado, approx. 150–200 deaths (current estimate).[122]

Two militants of an unknown faction shot and killed Ustaz Ja'afar Adam, a northern Muslim religious leader and Kano State official, along with one of his disciples in a mosque in Kano during dawn prayers on 13 April 2007. Obasanjo had recently stated on national radio that he would "deal firmly" with election fraud and violence advocated by "highly placed individuals." His comments were interpreted by some analysts as a warning to his vice president and 2007 presidential candidate Atiku Abubakar.[123]

In the 2007 general election, Umaru Yar'Adua and Goodluck Jonathan, both of the People's Democratic Party, were elected president and Vice President, respectively. The election was marred by electoral fraud, and denounced by other candidates and international observers.[124][125]

Yar'Adua's sickness and Jonathan's successions

Yar'Adua's presidency was fraught with uncertainty as media reports said he suffered from kidney and heart disease. In November 2009, he fell ill and was flown out of the country to Saudi Arabia for medical attention. He remained incommunicado for 50 days, by which time rumours were rife that he had died. This continued until the BBC aired an interview that was allegedly done via telephone from the president's sick bed in Saudi Arabia. As of January 2010, he was still abroad.

In February 2010, Goodluck Jonathan began serving as acting president in the absence of Yar’Adua.[126] In May 2010, the Nigerian government learned of Yar'Adua's death after a long battle with existing health problems and an undisclosed illness. This lack of communication left the new acting President Jonathan with no knowledge of his predecessor's plans. Yar'Adua's Hausa-Fulani background gave him a political base in the northern region of Nigeria, while Goodluck does not have the same ethnic and religious affiliations. This lack of primary ethnic support makes Jonathan a target for militaristic overthrow or regional uprisings in the area. With the increase of resource spending and oil exportation, Nigerian GDP and HDI (Human Development Index) have risen phenomenally since the economically stagnant rule of Sani Abacha, but the primary population still survives on less than US$2 per day. Goodluck Jonathan called for new elections and stood for re-election in April 2011, which he won.[127][128] However, his re-election bid in 2015 was truncated with the emergence of former military ruler General Muhammadu Buhari, mainly on his inability to quell the rising insecurity in the country. General Muhammadu Buhari was declared the winner of the 2015 presidential elections. General Muhammadu Buhari took over the helm of affairs in May 2015 after a peaceful transfer of power from the Jonathan led administration. On 29 May 2015, Buhari was sworn in as President of Nigeria, becoming the first opposition figure to win a presidential election since independence in 1960.[129] On 29 May 2019, Muhammadu Buhari was sworn in for a second term as Nigeria's president, after winning the presidential election in February 2019.[130]

Since 2023

The ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) candidate, Bola Tinubu, won the February 2023 presidential election to succeed Muhammadu Buhari as the next president of Nigeria. However, the opposition had accusations of electoral fraud in polls.[131] On 29 May 2023, Bola Tinubu was sworn in as Nigeria’s president to succeed Buhari.[132]

Democracy Day

Nigeria's Democracy day was originally celebrated on May 29, every year since General Olusegun Obasanjo emerged President in 1999. However, on June 12, 2018, General Muhammadu Buhari, as president, announced a shift in this date from May 29 to June 12, as from the year 2019. This was to commemorate the June 12th election of 1993, and the events that surrounded it.[133]

Historiography

The Ibadan School dominated the academic study of Nigerian history until the 1970s. It arose at the University of Ibadan in the 1950s and remained dominant until the 1970s. The University of Ibadan was the first university to open in Nigeria, and its scholars set up the history departments at most of Nigeria's other universities, spreading the Ibadan historiography. Its scholars also wrote the textbooks that were used at all levels of the Nigerian education system for many years. The school's output appears in the "Ibadan History Series."[134]

The leading scholars of the Ibadan School include Saburi Biobaku, Kenneth Dike, J. F. A. Ajayi, Adiele Afigbo, E. A. Ayandele, O. Ikime and Tekena Tamuno. Foreign scholars often associated with the school include Michael Crowder, Abdullahi Amith, J. B. Webster, R. J. Gavin, Robert Smith, and John D. Omer-Cooper. The school was characterised by its overt Nigerian nationalism and it was geared towards forging a Nigerian identity through publicizing the glories of pre-colonial history. The school was quite traditional in its subject matter, being largely confined to the political history that colleagues in Europe and North America were then rejecting. It was very modern, however, in the sources used. Much use was made of oral history and throughout the school took a strongly interdisciplinary approach to gather information. This was especially true after the founding of the Institute for African Studies that brought together experts from many disciplines.

The Ibadan School began to decline in importance in the 1970s. The Nigerian Civil War led some to question whether Nigeria was, in fact, a unified nation with a national history. At the same time, rival schools developed. At Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria, the Islamic Legitimist school arose that rejected Western models in favour of the scholarly tradition of the Sokoto Caliphate and the Islamic world. From other parts of Africa, the Neo-Marxist school arrived and gained a number of supporters. Social, economic, and cultural history also began to grow in prominence.

In the 1980s Nigerian scholarship, in general, began to decline, and the Ibadan School was hugely affected. The military rulers looked upon the universities with deep suspicion and they were poorly funded. Many top minds were co-opted with plum jobs in the administration and left academia. Others left the country entirely for jobs at universities in the West. The economic collapse of the 1980s also greatly hurt the scholarly community, especially the sharp devaluation of the Nigerian currency. This made inviting foreign scholars, subscribing to journals, and attending conferences vastly more expensive. Many of the domestic journals, including the Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, faltered and were only published rarely, if at all.[135]

See also

References

- Editorial Team (2018-12-12). "The Nri Kingdom (900AD - Present): Rule by theocracy". Think Africa. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- "The kingdom of Benin". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- "Kingdom of Oyo (ca. 1500-1837) •". 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- "Table content, Nigeria". country studies. 20 August 2001.

- "Historic regions from 5th century BC to 20th century". History World. 29 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "A short Nigerian history". Study country. 25 May 2010.

- "About the Country Nigeria The History". Nigeria Government Federal Website. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Ryder, A. F. C. "MISSIONARY ACTIVITY IN THE KINGDOM OF WARRI TO THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, vol. 2, no. 1, 1960, pp. 1–26. JSTOR 41970817. Accessed 4 July 2023.

- "Songhai | World Civilization". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- "Historical Legacies | Religious Literacy Project". Archived from the original on 2020-04-17. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- "The Transatlantic Slave Trade". rlp.hds.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-06-10. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "The Transatlantic Slave Trade | Religious Literacy Project". Archived from the original on 2020-06-10. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- Chioma, Unini (2020-02-01). "When I Remember Nigeria, I Remember Democracy! By Hameed Ajibola Jimoh Esq". TheNigeriaLawyer. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- "Nigerian Diaspora and Remittances: Transparency and market development". Nigerian Diaspora and Remittances: Transparency and market development. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Obasanjo, Olusegun (1980). My Command: an account of the Nigeria Civil War 1967–1970. Ibadan: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0435902490.

- Scerri, Eleanor (October 26, 2017). "The Stone Age Archaeology of West Africa" (PDF). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1, 31. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.137. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4. S2CID 133758803.

- Niang, Khady; et al. (2020). "The Middle Stone Age occupations of Tiémassas, coastal West Africa, between 62 and 25 thousand years ago". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 34: 102658. Bibcode:2020JArSR..34j2658N. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102658. ISSN 2352-409X. OCLC 8709222767. S2CID 228826414.

- Bergström, Anders; et al. (2021). "Origins of modern human ancestry" (PDF). Nature. 590 (7845): 232. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..229B. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03244-5. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 8911705938. PMID 33568824. S2CID 231883210.

- MacDonald, K.C. (April 2011). "Betwixt Tichitt and the IND: the pottery of the Faita Facies, Tichitt Tradition". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 46: 49, 51, 54, 56–57, 59–60. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2011.553485. ISSN 0067-270X. OCLC 4839360348. S2CID 161938622.

- Scerri, Eleanor M. L. (2021). "Continuity of the Middle Stone Age into the Holocene". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 70. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79418-4. OCLC 8878081728. PMC 7801626. PMID 33431997. S2CID 231583475.

- MacDonald, Kevin C. (Sep 2, 2003). "Archaeology, language and the peopling of West Africa: a consideration of the evidence". Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. pp. 39–40, 43–44, 49–50. doi:10.4324/9780203202913-11. ISBN 9780203202913. OCLC 815644445. S2CID 163304839.

- Schlebusch, Carina M.; Jakobsson, Mattias (2018). "Tales of Human Migration, Admixture, and Selection in Africa". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 19: 407. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021759. ISSN 1527-8204. OCLC 7824108813. PMID 29727585. S2CID 19155657.

- Eborka, Kennedy (February 2021). "Migration and Urbanization in Nigeria from Pre-colonial to Post-colonial Eras: A Sociological Overview". Migration and Urbanization in Contemporary Nigeria: Policy Issues and Challenges. University of Lagos Press. p. 6. ISBN 9789785435160. OCLC 986792367.

- MacDonald, Kevin C. (Sep 2, 2003). "Archaeology, language and the peopling of West Africa: a consideration of the evidence". Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge. pp. 39–40, 43–44, 48–49. doi:10.4324/9780203202913-11. ISBN 9780203202913. OCLC 815644445. S2CID 163304839.

- Van Beek, Walter E.A.; Banga, Pieteke M. (Mar 11, 2002). "The Dogon and their trees". Bush Base, Forest Farm: Culture, Environment, and Development. Routledge. p. 66. doi:10.4324/9780203036129-10. ISBN 9781134919567. OCLC 252799202. S2CID 126989016.

- Breunig, Peter; Neumann, Katharina; Van Neer, Wim (1996). "New research on the Holocene settlement and environment of the Chad Basin in Nigeria". African Archaeological Review. 13 (2): 116–117. doi:10.1007/BF01956304. JSTOR 25130590. S2CID 162196033.

- Richard Trillo (16 June 2008). "Nigeria Part 3:14.5 the north and northeast Maiduguri". The Rough Guide to West Africa. Rough Guides. pp. Unnumbered. ISBN 978-1-4053-8070-6.

- Bandama, Foreman; Babalola, Abidemi Babatunde (13 September 2023). "Science, Not Black Magic: Metal and Glass Production in Africa". African Archaeological Review. doi:10.1007/s10437-023-09545-6. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 10004759980. S2CID 261858183.

- Eze–Uzomaka, Pamela. "Iron and its influence on the prehistoric site of Lejja". Academia.edu. University of Nigeria,Nsukka, Nigeria. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (6 November 2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9030-6. S2CID 161611760.

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 9783937248462.

- Champion, Louis; et al. (15 December 2022). "A question of rite—pearl millet consumption at Nok culture sites, Nigeria (second/first millennium BC)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 32 (3): 263–283. doi:10.1007/s00334-022-00902-0. S2CID 254761854.

- Ehret, Christopher (2023). "African Firsts in the History of Technology". Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. p. 19. doi:10.2307/j.ctv34kc6ng.5. ISBN 9780691244105. JSTOR j.ctv34kc6ng.5. OCLC 1330712064.

- Champion, Louis; et al. (15 December 2022). "A question of rite—pearl millet consumption at Nok culture sites, Nigeria (second/first millennium BC)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 32 (3): 263–283. doi:10.1007/s00334-022-00902-0. S2CID 254761854.