History of Helsinki

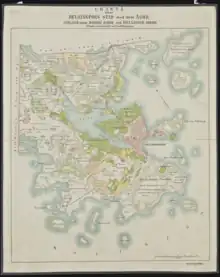

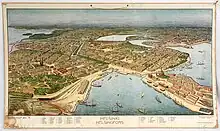

Helsinki is the capital of Finland and is its largest city. It was founded in the Middle Ages to be a Swedish rival to other ports on the Gulf of Finland, but it remained a small fishing village for over two centuries. Its importance to the Swedish Kingdom increased in the mid-18th century when the fortress originally known as Sveaborg was constructed on islands at the entrance to the harbor. While intended to protect Helsinki from Russian attack, Sveaborg ultimately surrendered to Russia during the Finnish War (1808-1809), and Finland was incorporated into the Russian Empire as part of the Treaty of Fredrikshamn. Russia then moved the Finnish capital from Turku to Helsinki, and the city grew dramatically during the 19th century. Finnish independence, a civil war, and three consecutive conflicts associated with World War II made Helsinki a site of significant political and military activity during the first half of the 20th century. Helsinki hosted the Summer Olympic Games in 1952, was a European Capital of Culture in 2000, and the World Design Capital in 2012. It is considered a Beta Level city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC), according to their 2012 analysis.

Kingdom of Sweden

Helsinki was founded by Swedish King Gustav I in 1550 as the town of Helsingfors. Gustav intended for the town to serve the purpose of consolidating trade in the southern part of Finland and providing a competitor to Reval (today: Tallinn), a nearby Hanseatic League city which dominated local trade at the time. In order to ensure the economic viability of the city, the king ordered the citizens of several other towns to relocate to Helsingfors, but the order did not achieve its intended effect. The Swedish acquisition of northeastern Estonia, including Reval, in 1561 during the Livonian War caused the Swedish crown to lose interest in building up a competitor to Reval, and Helsingfors languished as a forgotten village for decades thereafter.

In 1640, Helsingfors was moved south from its original location at the mouth of the river Vantaa (in Swedish: Vanda), but the improved harbour failed to attract traders. The plague of 1710 killed the greater part of the inhabitants of Helsingfors.[1] After Russia began to assert itself in the Baltic with the foundation of St. Petersburg, Helsingfors was fortified by the Swedish authorities to protect the city from Russian attacks. Construction of the island fortress Sveaborg (in Finnish: Viapori, today: Suomenlinna) began in 1748.

During the Finnish War, Russians captured Helsingfors in March 1808 and besieged the Sveaborg fortress until it surrendered in May. In addition, about one quarter of the town was destroyed by a fire in November of that year.[2]

Grand Duchy of Finland

Following the Russian victory in the war, sovereignty over Finland was transferred from Sweden to Russia in 1809, and in 1812 the Russian government relocated the Finnish capital to Helsinki from Turku (in Swedish: Åbo), a city across from Sweden on the Gulf of Bothnia. It was believed that the relative lack of Swedish influence in Helsinki, combined with its greater proximity to St. Petersburg, would make a Finnish government headquartered there easier to control. The fortress of Sveaborg also made the capital less vulnerable to an attack via the sea.

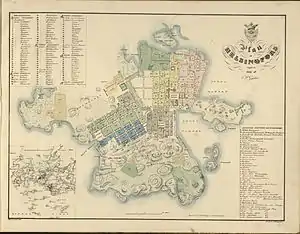

The Russian authorities rebuilt the city of Helsinki in neoclassical style, intending to turn it into a stylish modern capital along the lines of St. Petersburg. The plan by Johan Albrecht Ehrenström was initiated in 1816 by the German-born architect Carl Ludvig Engel. The plan focused on a large urban square, and the initial buildings constructed in the city included the Government Palace on the east side of the square (1822), the Helsinki Old Church (1826), the Orthodox Holy Trinity Church (1826), and Engels Teater (1827), the first theatre in the city. Following the Great Fire of Turku in 1827, The Royal Academy of Turku, at the time the country's only university, was also relocated to Helsinki. It was renamed the Imperial Alexander University in Finland (after Emperor Alexander I) and eventually became the modern University of Helsinki. Engel designed the Main University Building (completed on the west side of Senate Square in 1832) and the university library (1844), now the National Library of Finland. The relocation of the university consolidated the city's new role in the Grand Duchy and helped set it on the path of continuous growth.

The planned reinvention of the city as a national capital was finalized by the completion of the Helsinki Cathedral on the north side of Senate Square in 1852. Planned as the focal point of the square from the outset, the cathedral was to be located on the site of the existing Lutheran Ulrika Eleonora church. As such, its construction could not begin until after completion of the Helsinki Old Church, relocation of the altar and furnishings, and demolition of the Ulrika Eleonora church. Construction of the cathedral, originally known as the St. Nicholas Church, took from 1830 to 1852; thus it was not completed until 12 years after Engel's death. It remains a recognizable symbol of Helsinki, easily visible when approaching the city by boat from the Gulf of Finland.

During the 19th century, Helsinki became the economic and cultural center of Finland; as elsewhere, technological advancements such as railroads and industrialization were key factors behind the city's growth. The first Helsinki railway station opened in 1862 with service to Hämeenlinna. Beginning from the late 19th century, the Finnish language became more and more dominant in the city, since the people who moved in from the countryside mostly spoke Finnish. In the beginning of the 20th century, the city was already predominantly Finnish-speaking, although with a large Swedish-speaking minority. Nowadays the Swedish speakers are a small minority.

Helsinki's role as a capital resulted in its being the location of many prominent events in 19th and 20th century Finnish history. While the first 90 years under Russian rule were beneficial to the development of the city and the Finnish nation, the Russification of Finland began in 1899, during the reign of Nicholas II. In 1898, military officer Nikolay Bobrikov had been named by the tsar to be the Governor-General of Finland. Bobrikov's role was to hasten the Russification processes and assimilate Finland more fully into the Russian empire, by force if necessary. This made him extremely unpopular among the Finns, and in 1904 he was assassinated in Helsinki's Government Palace by Eugen Schauman.

20th century to present

Dissatisfaction with Russian rule and calls for independence continued, and in 1917 Finland took advantage of the Russian Revolution to obtain complete independence. Unfortunately, the sociopolitical turmoil that led to the Russian revolution also existed in Finland, and independence was immediately followed by a 3.5-month civil war. The socialist/communist faction of the population (Reds) rose against the conservative faction and government (Whites). The signal to begin hostilities was the lighting of a red lantern in the tower of the Helsinki Workers' Hall in the Hakaniemi district of the city on 26 January 1918. As Helsinki was within what was considered Red territory, the conservative Finnish government left the city and reassembled in Vaasa. The Finnish People's Delegation, the government of the Finnish Socialist Workers' Republic (as Red Finland was officially known), was established in Helsinki on 28 January 1918. German soldiers, allies of the White Guard, took Helsinki back from the Reds on 13 April 1918. While atrocities were committed by both sides during the conflict, thousands of Red prisoners perished after the war while being detained by the Whites at several locations, including the Suomenlinna fortress.

The new nation developed as a democratic republic amidst the interwar turmoil in Europe. According to the August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, Finland was placed in the Soviet Union's sphere of influence. Consequently, the Soviets attacked Finland on 30 November 1939 to begin the Winter War. Helsinki was bombed immediately after the war commenced, and then several additional times during the war. After an unfavorable peace agreement to end the war, Finland took the opportunity to become a "co-belligerent" with Nazi Germany in World War II, fighting a Continuation War against the Soviet Union only. This also resulted in multiple bombings of Helsinki from 1941 to 1944, with the most significant series being three massive raids in February 1944.

After the war, Finland was forced to pay reparations to the Soviet Union. Despite this, Helsinki and the rest of Finland thrived. A landmark event was hosting the Games of the XV Olympiad (1952 Summer Olympics). Finland's rapid urbanization in the 1970s, occurring late relative to the rest of Europe, tripled the population in the metropolitan area, and the Helsinki Metro subway system was built. The relatively sparse population density of Helsinki and its peculiar structure have often been attributed to the lateness of its growth. Helsinki was a European Capital of Culture in 2000, and the World Design Capital in 2012. It is considered a Beta Level city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC), according to their 2012 analysis.

Historical population of Helsinki

The population of the city grew rapidly after the relocation of the capital there in 1812, as demonstrated by the following table.

- 1810: 4,070 inhabitants

- 1830: 11,100

- 1850: 20,700

- 1880: 43,300

- 1900: 93,600

- 1925: 209,800

- 1960: 425,000

- 2001: 559,718

- 2012: 596,233

- 2017: 635,000

References

- Engström, NG. (1994). "[The plague in Finland in 1710]". Hippokrates (Helsinki) (in Finnish and English). 11: 38–46. PMID 11640321.

- Niukkanen, Marianna; Heikkinen, Markku. "Vuoden 1808 suurpalo". Kurkistuksia Helsingin kujille (in Finnish). National Board of Antiquities. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

Bibliography

External links

![]() Media related to History of Helsinki at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Helsinki at Wikimedia Commons