History of Lodi

The history of Lodi, a city and commune in Lombardy, Italy, draws its origins from the events related to the ancient village of Laus Pompeia, so named from 89 BC in honor of the Roman consul Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo.[1]

The settlement was founded by the Boii in a territory inhabited since the Neolithic period by the first nomadic farmers and breeders;[2] in later eras, the town became a Roman municipium (49 B.C.), a diocese (4th century) and finally - after coming under the control of the Lombards and the Franks - a free commune (11th century).[3] In the Middle Ages, by virtue of its privileged geographical position and the resourcefulness of its inhabitants, the township undermined the commercial and political supremacy of nearby Milan; the tension between the two municipalities resulted in a bitter armed conflict, in the course of which Ambrosian militias destroyed Laus twice.[4]

The city was refounded at the initiative of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa on August 3, 1158, a day remembered as the birth date of the new Lodi.[5] Due to the lordships and protection of the emperors, the municipality remained independent until 1335, when it fell under the rule of the Visconti, becoming one of the major centers of the Duchy of Milan.[6] In the mid-15th century it hosted the important negotiations between the pre-unitary Italian states that led to the Peace of Lodi (April 9, 1454); in the following decades - by virtue of the contributions of numerous artists and intellectuals - it experienced a season of great cultural splendor.[7]

Between the end of the sixteenth century and the mid-nineteenth century, the people of Lodi endured foreign occupations: the Spanish period was a phase of decadence, during which the town was transformed into a fortress; under Austrian rule, on the other hand, the city experienced an era of decisive economic expansion and urban renewal; the Battle of Lodi (May 10, 1796) opened the parenthesis of the Napoleonic twenty-year period.[8]

The decades following Italian unification saw the birth of the first factories as well as a resurgence of cultural life and civic activism.[9] Lodians also played an important role during the Resistance.[10] Since March 6, 1992, the city has been the capital of an Italian province.[11]

Laus Pompeia

Origins

In all likelihood, the Lodi territory was occupied since the Neolithic period by nomadic populations of farmers and ranchers.[13] As testified by archaeological findings, the first stable settlements - included within a triangle having vertices coinciding with the modern settlements of Gugnano, Lodi Vecchio and Montanaso Lombardo - date back to the Iron Age and are probably due to the settlement of some Ligurian tribes; the oldest find, preserved at the Lodi Civic Museum, is a bronze ring bearing an engraving depicting six geese.[13] The main village, which in a later period would have assumed the name of Laus, was located at Lodi Vecchio, about 7 km west of the site of the city of Lodi; in the third book of the Naturalis historia, Pliny the Elder expressly states that the village was founded by the Boii,[12] although historically that area was always controlled by the Insubri.[2] The Gallic toponym of the settlement has not been recorded accurately, which makes it prohibitive to reconstruct the exact etymology of the name "Laus".[14]

According to the Greek historian Polybius, the Romans arrived in the Po Valley between 223 and 222 B.C., years in which the consuls (Publius Furius Philus and Gaius Flaminius Nepos first, Marcus Claudius Marcellus and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio later) attacked and defeated the Insubrians.[15][16] This first occupation was short-lived, since the Celts - profiting from Hannibal's descent - regained their independence and maintained it for over twenty years.[16] It was not until 195 B.C. that Insubrian resistance was finally overwhelmed: from then until 49 B.C., Laus was part of the Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul.[16] Meanwhile, in 89 B.C., the village had been renamed "Laus Pompeia" in gratitude to Consul Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, who that very year had promoted the Lex Pompeia de Transpadanis, granting Latin right - that is, a status intermediate between full citizenship and subject status - to the inhabitants of the communities located north of the Po.[16] Strabo's measure had brought about a radical transformation not only from a legal point of view, but above all from a cultural and urban planning point of view: Latin was adopted as the official language and the settlement was rebuilt in a roughly rectangular shape, on the model of the castrum.[17] Forty years later, the Laudensians became full-fledged Roman citizens: Laus Pompeia acquired at the same time the rank of municipium, governed autonomously by a quadrumvirate and a town council, both elective.[17]

The Lodi Civic Museum preserves a fragment of black marble, dating from the first century AD, on which stands the epigraph: "Tiberius Caesar Augustus, son of Augustus, and Drusus Caesar, son of Augustus, had this gate built"; thus there must have been a wall.[18] As was the prerogative of any Roman city, there was also a forum, civil basilica, covered market, theater and baths.[18] Laus quickly became a flourishing agricultural, artisan and commercial center, mainly due to its privileged geographic location: the town was situated in the central part of the Po Valley, on the confluence of the roads from Placentia (Piacenza) and Acerrae (Pizzighettone) that led to Mediolanum (Milan), as well as at the point of intersection of these with the road from Ticinum (Pavia) that went up to Brixia (Brescia).[19] The earliest Laudense craftsman of whom there is evidence, specializing in the production of ceramics, was named Lucius Acilius.[20]

The most widely practiced cult in the territory - along with the veneration for Maia, Mefitis, and Mercury - was that of Hercules, who in late Roman times rose to symbolize state power and civilization prevailing over barbarism; this conspicuous diffusion was likely due to identification with an earlier Celtic deity, Ogmios.[17][21] The temple dedicated to Hercules stood outside the city, on the right bank of the Adda, where the church of Santa Maria Maddalena[17] is located in Lodi Nuova. As everywhere else in the Roman Empire, the veneration of the dead was also very much in vogue.[17] The presence of a Christian community in Laus - where the Berber soldiers Victor Maurus, Nabor and Felix were martyred in 303 - is attested as early as the third century, but the establishment of the diocese occurred only with Saint Bassianus between 373 and 374.[22] An epistle of St. Ambrose reports that in November 387 Bassianus invited Bishop Felix of Como and Ambrose himself to the consecration ceremony of the Basilica of the XII Apostles, one of the oldest churches in Lombardy, located in the suburb of Laus Pompeia.[20]

Barbarian invasions and the early Middle Ages

The barbarian invasions - which had affected the Lodi territory as early as 271, with the descent of the Juthungi and Alemanni - resumed with greater vigor at the beginning of the fifth century, so it was decided - for greater security - to relocate the episcopal see within the walls: the site chosen for the new cathedral of St. Mary was the south side of the ancient forum, where more than 1,400 Christians had been killed at the time of the persecutions of Diocletian and Maximian.[23][24]

On November 18, 401, the Visigoths of Alaric I crossed the Alps, setting their sights on the Po Valley and sowing devastation in the unprotected countryside; by the following February, the roads near Laus were impassable, so much so that the senator Quintus Aurelius Symmachus - in order to travel to Mediolanum to meet the emperor Honorius - had to pass through Pavia once he reached Piacenza.[24][25] In 452 Attila's Huns penetrated Italy, attacking Milan and hitting Laus Pompeia hard; the Lodians were also involved in the clashes between Flavius Orestes and Odoacer, king of the Heruli, as well as between the latter and Theodoric the Great, king of the Goths.[24][26] The Gothic War of the 6th century, fought by the Ostrogoths against the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, also inflicted extensive damage on the city.[24] Later it was the turn of the Lombards, who broke into northern Italy in 568 and conquered Milan the following year, but did not besiege and occupy Laus until 575, after the surrender of Pavia; in all likelihood the Laudensi capitulated due to a voluntary retreat of the front, due to the fact that the settlement was now considered indefensible.[24]

Although marshes - present in the territory since prehistoric times - were still extremely widespread, especially to the east of the city, an extension and rationalization of cultivation (vineyards, meadows, turkey oak, chestnut and even olive groves)[27] occurred at that time. Moreover, in spite of the protracted phase of decline, the first large-scale commercial activities began to develop: in a decree issued by the Lombard ruler Liutprand, dating back to 715, it is stated that traffic to and from the Adriatic was guaranteed in Laus by two river ports, located respectively at the confluence of the Lambro and Adda rivers in the Po.[28]

In 774 began the long domination of the Franks, during which the city was elevated to capital of a comitatus, that is, an administrative district of the Carolingian Empire.[29] Between the end of the ninth century and the beginning of the next, during the so-called "feudal anarchy," two incursions of the Magyars took place, which were followed by a period of quiet, due to the agreements made with them by King Berengar; however, these new incursions instilled a feeling of collective fear, which led a part of the population to take refuge inside some castles built to the south of the town.[29] On November 24, 975, with a diploma from Emperor Otto II of Saxony, Bishop Andrea obtained recognition of temporal power over the town and the surrounding territory within a seven-mile radius, thus becoming the first bishop-count of Laus: the ruler ceded landed estates, serf families, market management and tax revenues to Andrea; these prerogatives were expanded in July 981 with a second measure, which also entrusted the diocese with the administration of justice.[29] The figure of Bishop Andrea was crucial to the history of the Lodi community in the Middle Ages, as he laid the foundations for future city autonomy in the form of direct vassalage to the monarch, within the feudal system.[29]

Conflict with Milan

At the beginning of the 11th century, Laus constituted one of the greatest obstacles to the political and economic expansion of Milan, which was on its way to becoming a mercantile center of European stature: the Laudensians held almost exclusive control of commercial traffic across the territory's rivers, notably the Lambro, demanding tolls from boats that sailed up the waterways.[29]

Into this context came the actions of the Archbishop of Milan Ariberto da Intimiano, who fully embodied the imperialistic spirit of the time: when Lodi's bishop Notker, Andrea's successor, died in 1027, he availed himself of a faculty granted to him by the ruler Conrad II the Salic and imposed on the clergy of Laus the episcopal appointment of Ambrose II of Arluno, a canon who would act as his loyal vavasour.[27] Believing this arrangement to be an undue interference in their own affairs, the Laudensians adamantly opposed it and prevented the designated bishop from entering the city; Aribertus in turn did not desist and gathered an army around him, militarily occupying the countryside of Laus and laying siege to the village.[27] Realizing that they had little chance to resist, the citizens finally signed a peace agreement, swore an oath of allegiance to the archbishop and accepted the election of Ambrose II, who remained in office until 1051.[27]

The following decades saw the eruption of riots, always followed by raids and devastation, throughout the territories subjected to the Milanese.[30] This continuous state of tension resulted in the outbreak of a war between Laus and Milan: the conflict began in 1107, when the Laudensians removed Bishop Arderico from Vignate, accused of too subordinate an attitude toward the archdiocese presided over by Grosolanus.[30] In the meantime, at the initiative of the emerging merchant bourgeoisie, Laus had become a free commune, administered by an elective college of six consuls and renewed annually; the arengo, seat of the municipal government, was located a short distance from the basilica of the XII Apostles.[30] Despite having formed an alliance with Pavia and Cremona, also rivals of Milan, the Lodians appeared destined to succumb before the superior military power of the Ambrosian city, partly because the only defensive device was represented by the ancient Roman walls, dating back to the first century A.D. and therefore now obsolete; moreover, the town had gradually extended beyond the circle with a series of suburbs, around which a simple moat had been dug.[30][31] The capitulation of Laus was delayed only by Henry V, who, between the end of 1110 and the beginning of the following year, descended to Italy to be crowned emperor by Pope Paschal II, intimating the suspension of hostilities; on May 24, 1111 - while the sovereign was traveling between Verona and the Brenner Pass, on his way back to Germany - the Milanese decided to attack the city and destroyed it: first the walls were torn down, then the houses were looted and burned.[30]

The peace conditions imposed on the people of Lodi included a ban on rebuilding the damaged buildings and an oath of "perpetual subservience" to the victors; a further clause provided for the suppression of the weekly Tuesday market, one of the most important in the whole of Lombardy, which was a substantial source of income for the citizens.[30] In those years the people of Lodi had to submit to Milan without any form of autonomy, as evidenced by the fact that they were obliged to send a contingent of two hundred infantrymen at the siege of Como in 1126.[32] Nonetheless, Laus managed partly to rise again: the chronicler Ottone Morena - an eyewitness of the events - recounts that the surviving population abandoned the destroyed houses and "began to live in six new hamlets."[32] The basilica and cathedral of Santa Maria, spared from the devastation, continued to accommodate the Laudensians; at the same time, there was a very slow recovery of agriculture.[32]

In March 1153, shortly after his election, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa convened a diet in Constance to address issues related to Italian politics as well; Albernando Alamanno and Omobono Maestro, two Lodi merchants, requested an audience with the monarch and appeared before him in penitent clothes, protesting the wrong they had suffered at the hands of the Milanese.[33] The sovereign listened to them and decided to address a letter of reprimand to the Ambrosian authorities, which he entrusted to the missus dominicus Sicherius; the latter - ignoring the resistance manifested by the Laudensians themselves, who feared heavy retaliation from the rival city - delivered the imperial missive to the consuls of Milan, who, however, showered him with threats and forced him to flee.[33] The following year, being in Italy for the coronation ceremony, Barbarossa convened a diet in Roncaglia, where he arrived on November 30, 1154: on this occasion, Frederick received the remonstrances of the Lodi, Pavia and Como delegates against the actions of the Milanese, who in turn offered the monarch a large sum of money in order to obtain his approval, thus safeguarding their hegemony over the other Lombard municipalities.[33] The emperor rejected the proposal of the Ambrosian consuls, ordering them to "all submit to him, without any conditions," while the inhabitants of Laus were granted the reopening of the market, which benefited the local economy.[33]

The Milanese then had to wait until the ruler returned to Germany to strike their main enemies separately: first Cremona (summer 1157), then Pavia (winter 1157-1158), and finally Laus again (spring 1158).[33] In particular, the reprisal against the Laudensians was exceedingly severe: taxes were considerably tightened, some property was confiscated, and a ban was instituted on moving away from the village as well as on selling land owned for less than sixty years, so that no one would try to escape Milan's control; furthermore, all male citizens were required to repudiate loyalty to the emperor and swear complete obedience to the Ambrosian authorities, on pain of the community's ultimate annihilation.[33] Attempts at mediation by Bishop Lanfranco and Pope Adrian IV went unheeded: faced with the Lodians' denial, Milanese militias reached Laus on April 23, 1158, entered and sacked it, under the eyes of the inhabitants, who offered no resistance; within three days, crops were devastated, trees were felled and the town was entirely razed to the ground.[34] The refugees headed mainly for Pizzighettone and Cremona, where they were welcomed.[35]

The founding of New Lodi

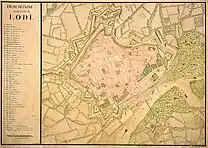

Frederick Barbarossa reappeared in Italy on June 8, 1158: encamped near Melegnano, he received a procession of Lodi exiles demanding justice.[35] With a view to downsizing Milan's supremacy, which he deemed dangerous, the sovereign personally promoted the rebuilding of the city, which he refounded the following August 3 in a more strategically appropriate location: the site chosen was in fact not the ruins of Laus Pompeia, but rather Mount Guzzone (or Colle Eghezzone), a modest trapezoidal-shaped rise located on the right bank of the Adda, not far from the point where a bridge known as "del Fanzago" and one of the river ports managed by the Laudensians already stood.[35][36] The chronicler Otto Morena describes the founding of the new settlement in these terms:[note 1][5]

"On the day of Sunday, August 3, 1158, the Most Holy Emperor Frederick mounted his horse, accompanied by several of his princes and knights and foot soldiers from Lodi, and all together they made their way to Mount Guzzone. When they had reached the mountain and had traversed it on all sides, [...] in the twinkling of an eye it began to rain copiously, a sign considered by all to be a good omen. When it stopped raining, the emperor invested with a banner the land on which the new city of Lodi was built. [...] The boundaries were established, starting from the side known as San Vincenzo; from the Adda to the moat of Porta Imperiale, then from the swamp that overtakes the aforementioned moat to another swamp that extends toward the Selvagreca, to the Adda to the east. When this task was over, the emperor and the Lodians returned to the camp with great joy and equal gladness."

Three months later - at the second Diet of Roncaglia - the sovereign promulgated the Constitutio de regalibus, by which he formalized the prerogatives of royal authority.[37] At the same time, Barbarossa granted the Laudensi exceptional privileges, including the right to build bridges over all waterways in the territory and to sail throughout Lombardy with full exemption from taxes; despite these benefits, the village developed slowly and with difficulty.[37][38] After having a system of fortifications erected around the town, the monarch established his headquarters in Lodi, from where he led a broad military offensive against the municipalities most reluctant to bow to his rule: the siege of Crema in 1159-1160 and the siege of Milan in 1161-1162 both ended in victory for Frederick's troops, who finally devastated the Ambrosian city with the participation of soldiers from Lodi, Cremona, Pavia, Como, Seprio and Novara.[39]

Barbarossa stopped in Lodi again in November 1163: on that occasion, the inauguration of the crypt of the cathedral took place, where the relics of the first bishop Bassianus were transferred from the basilica of the XII Apostles.[40] During the ceremony, the emperor and his wife Beatrice of Burgundy offered 35 pounds of gold for the completion of the new cathedral church,[41] the foundation stone of which had been symbolically laid on the very day the city was founded.[42][43]

When the sovereign returned to Germany, his officials were responsible for continued violence and prevarication throughout northern Italy, fueling growing discontent with imperial authority; in order to put an end to such abuse and to protect their own interests, while promoting the rebuilding of Milan, in 1167 a number of municipalities formed the Lombard League, a political-military alliance that the people of Lodi - out of gratitude to their founder - refused to join.[44] The city was then besieged by the coalition's army and forced to affiliate by force, "subject to loyalty to the emperor"; the conditions of surrender included the League's commitment to build at its own expense a new circle of walls two fathoms thick and twelve high, i.e., about one meter by six.[44] Frederick reacted by outlawing all rebellious municipalities with the sole exception of Lodi, to which on the contrary were renewed trade and tax concessions.[44] In the meantime, Barbarossa's absence from Italy lasted for almost seven years, during which time the confederation was further enlarged and consolidated: in 1173 the Lodians themselves organized and hosted a congress attended by delegates from the thirty-six allied cities.[44]

On May 29, 1176, fifty Lodi infantrymen took part in the decisive battle of Legnano, from which the imperial army - weakened by the defection of some German princes - exited heavily defeated; as a result, as sanctioned by the Peace of Constance, the monarch had to grant the municipalities almost total autonomy, definitively renouncing his intention to subjugate northern Italy.[45] Without Barbarossa's protection any longer, Lodi was called upon to face further contrasts with Milan, which were exacerbated when the new ruler Henry VI confirmed to the Laudensi the exercise of the prerogatives they had long enjoyed.[46] The military clash between the two cities resumed in 1193 and ended five years later with the stipulation of a pact of friendship: Lodi ceded to the Milanese the rights over the waters of the Lambro, obtaining in exchange the recognition of jurisdiction over its territory and the exclusive right to trade on the Adda.[46]

Meanwhile, the municipality's form of government had undergone a partial evolution: the town had been divided into six districts called "vicinities," each of which elected two of the twelve consuls who administered the city; these were assisted by a council known as the "credenza" and a council composed of representatives of the "paratici," i.e., the guilds of arts and crafts.[47] Due to the claims of the emerging artisan bourgeoisie, political life in Lodi became increasingly animated, to such an extent that two opposing factions began to form: the faction of the nobles and landowners - of Ghibelline tendency - was headed by the Overgnaghi family, while the party of the emerging classes - akin to the positions of the Guelphs - was led by the Fissiraga and Sommariva.[47] In order to protect the municipal institutions, the college of consuls was replaced by the figure of the podestà, a magistrate foreign to local disputes as he was an outsider:[48] the first to hold this office was the Brescian Giovanni Calepino, while his successor Petrocco Marcellino - a native of Milan - was the one who promulgated the statutes of the municipality.[49]

The age of lordships and the Renaissance period

The age of lordship

In the 13th century Lodi continued to grow: around 1220 the construction of the Muzza canal was undertaken, completed about a decade later, in which Lodi landowners and Milanese chieftains participated; this new hydraulic work contributed greatly to the flourishing of agriculture.[46] Until medieval times, the city was lapped by Gerundo Lake:[50] the land was largely marshy and unhealthy, but through the work of Benedictine, Cistercian and Cluniac monks - initiated in the 11th century and crowned by the opening of the Muzza[27] - it was reclaimed and made one of the most fertile regions in Europe.[51]

Meanwhile, the truce between the Italian municipalities and Emperor Frederick II of Swabia, Barbarossa's nephew, became increasingly precarious; on November 27, 1237, an armed clash was reached near Cortenuova, with an inauspicious outcome for the Lombard League.[52] Lodi also surrendered, and the sovereign made a solemn entry on December 12, deciding to turn the town into a Ghibelline stronghold: after ordering the removal of the Guelphs from the town, the monarch ordered the consolidation of the walls and the building of a castle alongside Porta Cremona, above the Selvagreca area, where he himself settled for short periods.[52] The Laudensi were also granted the right of minting for the first time: some silver and copper "grossi" minted under Frederick II's reign are preserved in the Civic Museum.[53] In 1243, outraged by the burning at the stake of a Franciscan friar, Pope Gregory IX inflicted an interdict on the city and suppressed the diocese, thus affecting the interests of one of the municipalities most closely linked to the emperor;[54] the Lodians regained the bishopric only nine years later, after the death of the sovereign and the subsequent decline of the Ghibellines.[52]

In 1251 the post of podestà was entrusted for a decade to Sozzo Vistarini, one of the most influential and wealthy members of the Laudense nobility, who had abandoned the Overgnaghi faction and placed himself at the head of the Guelphs.[52] The conferring of such vast power on a single person was a clear sign of a change in the political order, with the onset of the age of city lordships: formally, municipal bodies continued to be elected, but in practice - as was the case in most municipalities of central-northern Italy at that time - the government was held by a single family, represented by its head.[52] The Vistarini were succeeded by the Della Torre family of Milan with Martino, Filippo and then Napo; in the following years there were a number of tumults between the various sides aspiring to control Lodi, until in 1292 the Guelph party, headed by podestà Antonio Fissiraga, prevailed again.[55]

Towards the end of the 13th century, the city experienced considerable urban expansion, with the remaking of the city walls and the start of the construction of a number of new buildings, including the central core of Palazzo Broletto and the church of San Francesco;[56] the latter, in particular, is notable for the two "open-air" biforas on its façade, which constitute the first example of an architectural arrangement that between the 14th and 15th centuries spread throughout northern Italy.[57] Around 1300, the popular legend of the dragon Tarantasio was propagated: according to local folklore, the creature haunted the marshy waters of Lake Gerundo and, with its deadly miasmas, triggered the frequent malaria epidemics that affected the area.[50] In 1301, a conflict against the Ghibelline Matteo I Visconti, lord of Milan, began: after forming an alliance with the rulers of Pavia and Piacenza, Antonio Fissiraga gathered anti-Visconti forces in the spring of the following year and moved toward the Ambrosian city, where the outbreak of a revolt forced the Milanese nobleman to surrender without a fight and cede supremacy to the Della Torre.[55]

The situation changed dramatically in 1311, due to the descent of Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg into Italy: the sovereign militarily occupied the town founded by Barbarossa, allowing the return of the rival Fissiraga families.[55] The leader of the Ghibelline faction was Bassiano Vistarini, who had himself proclaimed lord of Lodi in 1321, with the support of the Visconti; he was succeeded by his sons Giacomo and Sozzino, who ruled until November 1328, when a popular uprising broke out: Guelph notary Pietro Temacoldo, a former miller originally from Castiglione d'Adda, led the uprising and seized power, handing over the keys of the city to Pope John XXII.[55][58] On August 31, 1335 - after suffering a long siege - Lodi fell under the blows of Azzone Visconti, losing its independence and becoming one of the most populous centers of the Duchy of Milan.[49] During this period peace was momentarily re-established among the feuding Lodi families and work was begun on the building of the castle of Porta Regale, completed in 1373; meanwhile, the crisis of the 14th century led to a protracted phase of economic and demographic decline.[49]

Following the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti in September 1402, the Ambrosian administration saw its ability to exercise government over peripheral territories greatly diminished. Luigi Vistarini took advantage of this weakness to proclaim himself rector of Lodi, but his initiative was harshly opposed by rival factions, who provoked scuffles and succeeded him with Antonio II Fissiraga.[59] However, the latter adopted a benevolent political line toward the Visconti, arousing widespread discontent that eventually favored the conquest of power by Giovanni Vignati, wealthy heir of a noble Guelph family of the Contado;[note 2] supported by the pope, the Republic of Florence and the Cavalcabò of Cremona, he placed himself in command of a small army and was appointed lord of Lodi on November 23, 1403.[59] Three years later, after promoting an unsuccessful war effort against Milan, Vignati received the title of Venetian patrician: the Republic of San Marco looked favorably on the small lordships born from the fragility of the Visconti regime.[59] Between 1409 and 1410, the Lodi aristocrat also seized Vercelli, Melegnano and Piacenza, buying the latter for the price of 9,000 florins from some French mercenaries who had invaded it; on September 16, 1412, the new Duke Filippo Maria signed an agreement in which he formally recognized Vignati's authority over the territories south of Milan, but at the same time bound him to political and military subordination to himself.[59]

On December 9, 1413, from the Laudense cathedral, Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg and Antipope John XXIII issued the bull convening the Council of Constance, which would later resolve the Western Schism; for about a month the city was the seat of ambassadors from all parts of Italy, and Giovanni Vignati, in exchange for his hospitality, was given the hereditary title of "count of Lodi, Chignolo and Maccastorna," briefly becoming one of the preeminent figures on the European political scene.[60] In the summer of 1414, after managing to recapture Piacenza, the Duke of Milan captured Giacomo Vignati, one of the Lodi nobleman's two sons.[61] The latter was then forced to negotiate again and to declare himself a vassal of the Visconti, taking an oath of allegiance; later, having gone to the castle of Porta Giovia to obtain the release of his son provided for in the agreement, he was arrested by surprise and sentenced to death.[61] Meanwhile, the condottiero Francesco Bussone, known as "the Carmagnola," occupied Lodi and killed Ludovico, Vignati's other heir: the city of Barbarossa thus became to all intents and purposes part of the Duchy of Milan again.[61]

Peace of Lodi and the Renaissance

In 1419, Gerardo Landriani Capitani, a devotee of literary studies and in contact with the most distinguished humanists of the time, became bishop of Lodi;[62] he was responsible for the unexpected discovery, among the documents of the cathedral chapter, of a manuscript containing some rhetoric treatises traditionally attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero.[63] The codex was of considerable importance in the rediscovery of the classical art of oratory since it included - in addition to De inventione and Rhetorica ad Herennium, works that were widespread in the Middle Ages - De oratore and Orator, of which only fragments were known until then, and the almost complete text of Brutus, of which only the title was previously known.[note 3][63]

After the death of Filippo Maria Visconti, northern Italy again fell into disarray: in Milan the Golden Ambrosian Republic was established, while the people of Lodi proclaimed their membership in the Serenissima, which ratified their accession on October 12, 1447.[64] The situation changed unexpectedly when Francesco Sforza took command of the Ambrosian troops: after the defeat of Caravaggio, Venice ceded Lodi to the Milanese, sparing it at least from pillage; however, the town was besieged and devastated by Francesco Piccinino's soldiers.[64] A long series of riots and clashes followed, after which Sforza was appointed the new duke of Milan on September 11, 1449.[64] Because of their border position, Lodi and the neighboring townships were repeatedly plundered by the different armies at war with each other, but already the following year negotiations for an understanding began, which took place right in the city at Palazzo Broletto: the agreement, known as the "peace of Lodi," was signed on April 9, 1454 by representatives of the main Italian pre-unitary states (Duchy of Milan, Republic of Venice, Republic of Florence, Republic of Genoa, Margraviate of Mantua, Kingdom of Naples, Duchy of Savoy, and March of Montferrat).[65][66] The historical importance of the pact lies in the fact that it gave the peninsula a new political-institutional structure that - by containing the expansionist ambitions of individual regional governments - ensured a substantial territorial balance for forty years, consequently helping to foster the artistic and literary flowering of the Renaissance.[66][67]

In the following decades, marked by the long bishopric of the humanist and patron Carlo Pallavicino (1456-1497), Lodi experienced one of its richest eras from an artistic and cultural point of view: intellectual Maffeo Vegio, music theorist Franchino Gaffurio and architect Giovanni Battagio worked during this phase; works such as the Ospedale Maggiore, Mozzanica palace, the treasure of San Bassiano[note 4] and the civic temple of the Incoronata, considered the city's most prestigious monument and one of the greatest masterpieces of the Lombard Renaissance,[56][68] also saw the light. Around 1470, the renovation of the cathedral was started with the construction of the sacristy and stained glass windows, while the church of San Francesco was enlarged and frescoed;[69] meanwhile, the Duke of Milan had the bridge over the Adda rebuilt with two fortifications at the ends, consolidating the defense system by the arrangement of the octagonal ravelin and the remodeling of the Rocchetta.[70]

The modern era

Spanish rule

The period of stability guaranteed by the peace of Lodi came to an end in 1494, when King Charles VIII of France - encouraged by Ludovico il Moro - invaded the peninsula with an army of 30,000 troops, initiating the so-called "ruin of Italy"; starting from that moment, for about twenty years raids and pillages followed one after the other, which also affected the territory of Lodi.[71] The episode of the challenge of Barletta (February 13, 1503), in which Fanfulla da Lodi, a captain of fortune in the service of the Iberians, took part,[72] is part of the conflict between the French and the Spanish. Between June 1509 and September 1515, while the war of the League of Cambrai raged, Barbarossa's city was occupied several times: first by Louis XII's men, then by the Swiss and then by the Venetians, who, however, abandoned it almost immediately.[71] The Treaty of Noyon in 1516 finally assigned the Duchy of Milan to the French, who emerged victorious from the Battle of Marignano.[71]

After a few years, the newly elected Emperor Charles V of Habsburg - who had come into conflict with Francis I - sent a corps of Swiss mercenaries to take possession of Lombardy; they arrived in Lodi in May 1522 and plundered it.[71] From then on, the village became the headquarters of the supreme commander Fernando d'Ávalos: it was in Lodi that the imperial troops that captured the French monarch during the Battle of Pavia on February 24, 1525 gathered.[73] In June 1526, the population of Lodi - exasperated by the abuse of power perpetrated by Fabrizio Maramaldo's Spanish garrison - began an armed insurrection; condottiero Lodovico Vistarini led the rioters, drove the occupiers away and welcomed the army of the League of Cognac, hostile to Charles V, into the city.[74] The imperial militia reacted harshly, placing Lodi under siege and striking it with a heavy cannonade that breached the city walls not far from the castle, in the place that was later renamed "via del Guasto"; however, the people of Lodi managed to hold out until the end of the conflict, sanctioned by the Peace of Cambrai (1529).[74] In 1535, upon the death of Francesco II Sforza, the Duchy of Milan was formally annexed to the domains of Charles V; when the emperor visited Lodi in August 1541, he was hosted at the Vistarini palace, in the mansion of the man who had spearheaded the uprising fifteen years earlier.[74]

The city was not involved in the subsequent war events, which allowed for the construction of the bell tower of the cathedral, begun in 1538 based on a design by Callisto Piazza and left unfinished for military security reasons, on the instructions of the authorities.[74] At that time the municipality was administered by a castellan and a podestà appointed by the Spanish governors, flanked by a decurion council and an executive council composed of representatives of the aristocratic families.[75] The second half of the 16th century saw the radical Mannerist renovation of the San Cristoforo complex, carried out by architect Pellegrino Tibaldi; frescoes were painted in the cathedral by Antonio Campi, which have been lost, and the marble rose window on the façade was created.[76][77] Meanwhile, Bishop Antonio Scarampi established the seminary, founded a boys' orphanage and implemented the renewal measures promoted by the Council of Trent, working under the auspices of Cardinal Carlo Borromeo.[77]

In the seventeenth century, despite the fact that Lodi continued to enjoy peace, the Hispanic authorities imposed the complete rebuilding and enlargement of the city walls, transforming the town into a stronghold; the Inquisition tribunal[78] was also particularly active at that time. The climate of tension, the conditions of isolation and the continuous demand for taxes produced a marked economic depression, which was accentuated by the plague epidemic of 1630, caused by the passage of the Landsknechts through the city; the lazaret was set up at Porta Cremona.[79] The drastic provisions adopted by health judge Pietro Boldoni, who decreed the immediate suspension of markets and a total curfew, made it possible to moderate the spread of the contagion: the disease caused 200 victims out of more than 13,000 inhabitants, resulting in one of the lowest mortality rates in all of northern Italy.[79]

As can be deduced from the text of a meticulous report addressed to the Spanish dignitary Filippo de Haro, the seventeenth-century economy was predominantly based on agriculture and animal husbandry; the most sold products were ceramics, linen cloths, butter and Granone Lodigiano, considered the progenitor of all grana cheeses.[78] Towards the end of the century there was a revival of cultural life: the first theater, still reserved for the nobility, was inaugurated, and a number of scientific-literary sodalities were formed, attended by intellectuals such as the poet Francesco De Lemene, a member of the Accademia dell'Arcadia; in the same years the first public schools were created, while the congregation of the Filippini laid the foundations for the book collection that would later form the civic library.[80]

The Austrian period

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) determined the beginning of Austrian rule, sanctioned by the Treaties of Utrecht (1713) and Rastatt (1714).[81] At first the new rulers, who were initially unappreciated by the people of Lodi,[82] focused their attention on a few measures of a mostly symbolic nature: in 1721 the wooden guardhouse used by the Iberian soldiers in the Piazza Maggiore was removed, while in 1724 - at the head of the bridge over the Adda River - a statue of John of Nepomuk, a saint very dear to the sailors of Central Europe, was placed.[83]

Later on, the government of Maria Theresa of Habsburg (1740-1780) introduced some significant reforms in Lodi as well, which favored the start of a remarkable economic recovery, especially through the multiplication and rational reorganization of agricultural land according to the principle of crop rotation, which soon became an established practice.[84] In order to protect public health, burials in churches and on churchyards were prohibited: the opening of the first two suburban cemeteries in Riolo and San Fereolo dates back to that period.[85] Other innovations involved the adoption of odonymy and the reorganization of local administrations: in this regard, Emperor Joseph II of Habsburg-Lorraine established the abolition of feuds and instituted eight provinces including that of Lodi, which replaced the ancient Contado and also included Pandino, Gradella, Nosadello, Rivolta, Spino, Agnadello as well as the rest of the Gera d'Adda.[86]

During the course of the century there was a strong urban development that transformed the face of the city under the banner of late Baroque and Rococo architecture, changing the original structure of the ancient medieval settlement: The churches of Santa Maria del Sole,[87] Santa Maria Maddalena,[88] San Filippo Neri[89] and Santa Chiara Nuova[90] were built, while the interior of the cathedral was remodeled by Francesco Croce to adapt it to the style of the time, and the Bishop's palace was entirely renovated by Giovanni Antonio Veneroni.[86][91] In the same years, Palazzo Barni, Palazzo Modignani, Palazzo Sommariva and a new theater were also built, after the fire that had destroyed the previous one; numerous other buildings were greatly expanded or renovated, such as Palazzo Galeano, the town hall and the Ospedale Maggiore, the latter designed by Giuseppe Piermarini, the same architect of the Royal Villa of Monza and La Scala in Milan.[86][92] Several monasteries and minor religious buildings were deconsecrated and in some cases demolished to make room for new private dwellings; the main streets were also widened by the removal of guard stones and the demolition of porticoes.[93] At the same time, the bastions erected during the Spanish rule of the seventeenth century were dismantled almost completely; in their place, a ring road approximately 3700 m long was laid out, connecting all the city gates, which had been used for centuries as customs barriers and restored according to the canons of the neoclassical style.[94]

In the meantime, the influence of the Enlightenment movement had also reached the Laudense territory: many religious orders were suppressed, the library was opened to the public, the original nucleus of the future Civic Museum was formed, and the first hot-air balloons were experimented with; a new hospital was also inaugurated and a higher education course was established.[86] In March 1770, the then 14-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart stopped briefly in the city, at a hotel located in the "Gatta" locality, while he was traveling with his father Leopold between Milan and Parma; during his stay, the musician completed the writing of the first of his twenty-three string quartets, known as the Lodi Quartet.[83]

Contemporary era

The Napoleonic 20-year period

In 1792 the Archduchy of Austria went to war against the First Republic of France, which had arisen as a result of the revolutionary events of three years earlier; in March 1796, in order to relieve the pressure on the German front, the Directory decided to take military operations to Italy, entrusting the command of the army to the emerging 26-year-old general Napoleon Bonaparte.[95] After forcing the Kingdom of Sardinia, an ally of the Habsburg monarchy, to surrender in just three weeks, the French continued their march south of the Po River and crossed it on May 7 between Piacenza and San Rocco al Porto, with the further aim of confronting the Austrian army and inflicting substantial losses on the enemy.[95][96]

The vanguard of Napoleon's troops, coming from Casalpusterlengo, reached Lodi in the early morning hours of May 10; by that time the bulk of the Archducal forces - under the orders of Johann Peter Beaulieu - had already moved further north, leaving a contingent of 10,000 troops to guard the bridge over the Adda, perched in the Revellino fortress.[97] Hostilities began with a prolonged artillery duel, which caused extensive damage in the neighborhoods located near the river; the church of San Cristoforo and other places of worship were turned into hospitals to accommodate the wounded and displaced.[98] Bonaparte, who was watching the clash from the bell tower of St. Francis, sent two cavalry divisions in search of a ford, with the aim of attempting a quick outflanking maneuver.[98] The action was successful and proved decisive for the French victory: the Habsburg troops, attacked on three sides, were in fact forced to retreat.[98][99]

The Battle of Lodi represented the first significant military and political success of Napoleon, who entered Milan triumphant on May 15 after receiving the keys of the Ambrosian city from the hands of Francesco Melzi d'Eril at Palazzo Sommariva.[100] The historical importance of these events justifies the presence of many streets and squares dedicated to the bridge over the Adda: for example, in the VI arrondissement of Paris, on the rive gauche, there is the "rue du Pont de Lodi".[101] About the decisive combat of the Italian campaign, Bonaparte had written:[102]

"It was only on the evening of Lodi that I began to think of myself as a superior man, and that I harbored the ambition to implement great things that until then had found a place in my mind only as a fantastic dream."

Meanwhile, Antoine Christophe Saliceti, commissioner of the Directory, had ordered the confiscation of the treasure of Saint Bassianus and had it transported to France.[103]

_Duca_di_Lodi.png.webp)

As early as 1789 there was a secret Jacobin circle in the city, founded by Andrea Terzi, which met at the Osteria del Gallo on Corso di Porta Cremonese.[95] The assertion of Napoleon's troops triggered great celebrations, the bourgeoisie began wearing tricolor cockades, and numerous freedom trees were planted, one of which was even in the seminary; in 1797, when the Cisalpine Republic was formally established, the religious institutions of Sant'Agnese, Sant'Antonio, San Cristoforo and San Domenico were suppressed.[103] After an ephemeral interlude in which the Austro-Russians of Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov occupied the whole of Lombardy (1799), General Bonaparte - who in the meantime had proclaimed himself "first consul" with the coup of 18 Brumaire - succeeded in reconquering the Po Valley following the Battle of Marengo, returning to Lodi in June 1800.[103] In this circumstance the city of Barbarossa lost the rank of capital it had acquired in 1786, during Habsburg rule: the Lodi territory was annexed to the Department of the Alto Po, with its administrative headquarters in Cremona.[103]

After Napoleon's coronation as Emperor of the French, north-central Italy became a kingdom ruled by Bonaparte himself (1805); Francesco Melzi d'Eril was appointed duke of Lodi, while Bishop Gianantonio Della Beretta received the title of baron.[104] From 1806 to 1816, the three chiosi[note 5] (Porta Cremonese, Porta d'Adda, Porta Regale) and the neighboring municipalities of Arcagna, Boffalora, Bottedo, Campolungo, Cornegliano, Montanaso, Torre de' Dardanoni and Vigadore[105] were temporarily aggregated to the municipality. In May 1809 - on the initiative of Viceroy Eugene of Beauharnais - a monument commemorating the Battle of the Bridge, created by Giocondo Albertolli, was placed in Piazza Maggiore; the work was destroyed in 1814 and the granite guard stones that surrounded it were reused to delimit the cathedral forecourt.[104][106]

Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia

French rule ended with the defeat at Leipzig in October 1813, in which Bonaparte was defeated by the Sixth Coalition army.[104] On April 26, 1814, the Austrians returned to Milan, and eleven months later, in deference to the resolutions of the Congress of Vienna, the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia was born; shortly afterwards Lodi obtained the status of "royal city."[note 6][104] Emperor Francis II of Habsburg-Lorraine visited the town of Lodi in the last days of December 1815 and spent New Year's Eve at Modignani Palace; the following January, upon the establishment of the seventeen territorial districts of the state, Lodi became the capital - along with Crema -[note 7] of the province of the same name.[104]

During the Restoration years, Barbarossa's city developed mainly on two fronts: on the cultural side, three new newspapers saw the light of day, the municipal high school was inaugurated (which counted Giacomo Leopardi among the contenders for professorships), and other educational institutions sprang up, including the Maria Cosway women's college and the Barnabite men's college, whose return was authorized by Bishop Alessandro Maria Pagani; in terms of urban planning, public oil lighting was introduced in 1819, and in 1838, on the occasion of Ferdinand I of Austria's visit, the fortifications between Porta Regale and Porta Cremona were demolished, making way for a tree-lined promenade with an obelisk bearing Latin epigraphs.[107][108]

The insurrectional uprisings of 1820-1821 and those of 1830-1831 passed almost unnoticed, but the situation changed in the following decades: the most politically dynamic environment was the high school where, especially among the teaching staff, a strongly progressive group was active, coordinated by Luigi Anelli, Paolo Gorini, Pasquale Perabò and Cesare Vignati.[109] However, republican and anti-Austrian positions were not widespread among the population, so much so that very few Lodians took part in the fighting of the Five Days of Milan; nevertheless, on March 23, 1848 - when news of the insurgents' victory reached them - a riot broke out, which was immediately quelled by the 4,000 imperial soldiers guarding Lodi.[110] The following night the troops of Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky, in retreat, passed through the town in their march toward the fortresses of the Quadrilatero: the liberals were thus able to come out into the open, forming a provisional government led by the moderate Carlo Terzaghi.[110] The army of the Kingdom of Sardinia - which in the meantime had declared hostilities to the Austrians, starting the First War of Independence - arrived in the city on March 30, personally commanded by King Charles Albert of Savoy; the sovereign issued a proclamation from Lodi urging Italians to support the Risorgimento cause.[111] Several dozen young men from Lodi, including Eusebio Oehl and Tiziano Zalli, enlisted as volunteers; nine of them died in battle.[111]

In the following summer, the outcome of the conflict was fortuitous for the Imperials, who occupied the city again on August 3.[112] After the Salasco armistice, the Habsburg authorities adopted a more repressive policy toward dissidents: Anelli and Vignati were removed from teaching, General Saverio Griffini was exiled to Switzerland, and physician Francesco Rossetti - accused of Mazzini conspiracy - was arrested.[113] The new monarch Franz Joseph I and his wife Elizabeth of Bavaria visited Lodi in 1857; two years later, Bishop Gaetano Benaglia - close to progressive demands and sensitive to the needs of the rising working class - openly took a stand against the Austrian regime.[114] Meanwhile, the Second War of Independence had broken out, which saw Napoleon III's French Empire siding with the Piedmontese: after the Battle of Magenta and the Melegnano clashes, on June 10, 1859, the Hapsburg troops finally left Lodi, setting fire to the bridge over the Adda.[114] Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy went to the city on September 20; only a month later the Rattazzi Decree was promulgated, by which the territory of Lodi was assigned to the province of Milan:[note 8] the municipality of Lodi, which at that time had 25 660 inhabitants, was thus deprived once again of its prerogatives as capital.[115]

The Peace of Zurich, stipulated on November 10, 1859, formalized the passage of Lombardy to the Kingdom of Sardinia.[115] On May 5, 1860, two Lodians (Luigi Martignoni and Luigi Bay) departed from Quarto with the Expedition of the Thousand; counting those who were added later, in various stages, a total of 234 young men took part, distinguishing themselves especially in the attack on Milazzo and the fighting at Pizzo Calabro.[116]

Kingdom of Italy

On March 17, 1861, the Parliament proclaimed the Kingdom of Italy with the participation of the deputy elected in the Lodi constituency; in the following decades the city underwent a sudden change, evolving into a center at the forefront in several sectors.[117] The first industries were established, including Lanificio Varesi (1868), Polenghi Lombardo (1870), Officine Sordi (1881), Officine Meccaniche Lodigiane (1908), Linificio Canapificio Nazionale (1909), Officine Meccaniche Folli-Gay (1922), Officine Curioni (1925) and Officine Elettromeccaniche Adda (1926).[118] Lodi was also the birthplace of Italy's first popular bank, namely the Banca Mutua Popolare Agricola, founded in 1864 by the lawyer and activist Tiziano Zalli - a former opponent of the Austrian regime and patron of Giuseppe Garibaldi - for the purpose of supporting agrarian and artisan activities.[115]

The territory was also affected by the infrastructural development that characterized the post-unification era: in 1861 the Milan-Piacenza railway line, part of the great Italian backbone route, was inaugurated; three years later, based on a design by the Milanese architect Gualini, the new masonry bridge over the Adda was completed, which later became one of the symbols of the city; in 1880 four suburban steam tramways (the Milan-Lodi, the Lodi-Treviglio-Bergamo, the Lodi-Sant'Angelo and the Lodi-Crema-Soncino) came into operation; in 1886 the construction of the monumental cemetery, better known as the "Maggiore", was undertaken.[115][119] Other significant interventions of an urbanistic nature concerned the redevelopment of the area of Piazza del Duomo, the enlargement of Piazza Ospitale and the construction of a road connection with the railway station (Piazza Castello- Viale Dante), to which was added - after a modest expansion of the built-up area towards the south - the building of the first lot of council housing, promoted by Tiziano Zalli.[120] At that time, Lodi was still almost entirely enclosed within the ring road corresponding to the medieval walls; outside that perimeter, in addition to several farmsteads, there were a number of hamlets (San Grato, San Fereolo and San Bernardo), located at the crossroads between the regional and local roads, at a distance of between 2 and 5 km from the center.[121] In social terms, there was a prolonged phase of demographic stagnation, brought about by the loss of the status of capital and especially by the rapid decline of the traditional agricultural economy, which for centuries had been the main source of livelihood for many Lodians.[122][123] In 1877 the suburban municipalities of Chiosi Uniti con Bottedo and Chiosi d'Adda Vigadore[124] were annexed to the municipality.

One of the most notable consequences of the city's industrial transformation was the rise of consciousness on the part of the working class: in the last decades of the century several strikes took place and the first organized "red leagues" were formed, fighting to defend workers' elementary rights.[125] In 1868 Enrico Bignami founded the socialist periodical La Plebe, the first to publish the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Benoît Malon; in 1873 the Lodi socialist section was the only one active in the whole kingdom and sent its delegates to the Sixth Congress of the International in Geneva, so much so that Engels himself had to define Lodi as "the only pied-à-terre of Marxism in Italy."[125] Two years later, La Plebe inaugurated its Milan editorial office, which saw the journalistic debut of Filippo Turati.[126] Parallel to the socialist faction, the Catholic social movement also established itself, which had as its press organ Il Lemene, later to become Il Cittadino.[127] At that time Lodi was beyond lively from a cultural point of view: in addition to those already mentioned, there were numerous other periodicals, including Il Corriere dell'Adda, Il Proletario, Il Fanfulla, La Zanzara, L'Unione, La Difesa, Rococò, Sorgete! and Il Rinnovamento; in addition, the Municipal Historical Archives came into being, the Civic Museum was opened to the public, the theaters in operation were increased from one to four, new high schools were established, and two research institutions, namely the Experimental Dairy Institute and the Experimental Station for Practiculture, were established.[117]

During the capture of Rome and the colonial wartime operations in Libya, notably in the Battle of Zanzur in 1912, the Regiment "Cavalleggeri di Lodi" of the Royal Army, which had been stationed in the city for a short interval of time, distinguished itself; the exploits of the unit were sung by Gabriele D'Annunzio in the fourth book of Laudi del cielo, del mare, della terra e degli eroi.[note 9][123] World War I, as a result of which 331 Lodians died and a great many more were maimed or wounded, was experienced much more tragically.[128] The conflict also contributed to increased awareness of their role on the part of women, who began to replace their husbands in the fields and factories; poet Ada Negri, the daughter of a woolen mill worker, was among the founders of the National Women's Union.[129]

Meanwhile, the lawyer Riccardo Oliva - an exponent of the UECI, which later merged into the PPI - had become the first Catholic mayor of Lodi in 1914; his term of office was deeply conditioned by the wartime emergency and serious financial difficulties.[130] Subsequent local consultations - held in 1920 with universal male suffrage - rewarded the PSI instead, allowing workers and artisans to take part in the city's government; the leadership of the administration was entrusted to sculptor Ettore Archinti, who promoted a broad program of reforms, interrupted, however, by the Communist split and especially by the rise of Fascism.[131] The 1922 municipal elections took place a few weeks after the march on Rome, in a climate of intimidation and violence that had induced the Socialists not to run for office: the squadrists had forcibly occupied the town hall, the Carabinieri barracks, the railroad yard, the jail and the CGIL headquarters; the new mayor was accountant Luigi Fiorini, elected on the National Blocs list, the result of an alliance between the liberals and the fascists themselves.[132]

Under Benito Mussolini's regime, Lodi lost institutional importance: democratic organs were suppressed, the district was abolished, and the mayor was replaced by a podestà, appointed by the government for five years and revocable at any time; all employees of the administration were also required to join the National Fascist Party.[133] During the 1930s, rationalist architecture became popular and a number of construction sites were completed, including that of the road underpass on Via San Colombano; however, the substantial urban renewal plan heralded by the local authorities remained largely unfinished and many public services were downsized or suspended.[134]

World War II and the Resistance

Unlike the previous war, World War II thoroughly involved the population, which was subjected to strict rationing of basic necessities and affected by bombings that caused numerous civilian casualties: the most dramatic episode occurred shortly after 8 a.m. on Monday, July 24, 1944, when an aerial formation targeted homes in the historic center, causing 39 deaths - mostly women and children - in the block between Via Solferino, Via Fanfulla and Via Santa Maria del Sole; another similar incident took place on April 2, 1945, causing another 40 casualties.[135][136] The city also housed some 10,000 evacuees from Milan, who were mainly housed in the Porta Regale castle and school buildings, while canteens were set up at the Municipal Assistance Board.[137][138]

Previously, the news of Mussolini's dismissal and the consequent fall of Fascism (July 25, 1943) had been welcomed by public opinion: many residents of Lodi - by then exasperated by the hardships of war and the abuses of the Blackshirts - had taken to the streets and reached the party offices, destroying the symbols of the regime.[139] A few hours after the Cassibile armistice was announced, Wehrmacht soldiers occupied Lodi in force, imposing a night curfew, confiscation of weapons and a ban on meetings.[140] In the meantime, the first Resistance movements arose secretly: the local section of the National Liberation Committee was formed in October 1943 with a Christian Democrat majority and a well-organized Communist group, flanked by Socialists and representatives of all secular parties; clandestine gatherings were held in the Cornalba pharmacy in Viale Dalmazia or at the San Francesco college, under the protection of Father Giulio Granata.[141] Despite the threat of the death penalty for renegades, the majority of young Lodi men shied away from enlisting in the militias of the Italian Social Republic, the puppet state created by Mussolini;[142] many of them decided instead to join the mountain formations of the Freedom Volunteer Corps, leaving mainly for the Bergamasque Pre-Alps, Oltrepò Pavese and Upper Piedmont, where a unit renamed "Fanfulla" was active and participated in the Ossola Partisan Republic.[143]

The first popular agitations broke out in November 1943 on the initiative of women workers at the woolen mill, imitated in the following months by workers at Officine Adda and other city factories.[144] On July 9, 1944, a deadly attempt was also made against gerarca Paolo Baciocchi, prefectural commissioner of Sant'Angelo.[145] Fascist retaliation was immediate: five Laudensi partisans (Oreste Garati, Ludovico Guarnieri, Ettore Maddè, Franco Moretti and Giancarlo Sabbioni), all belonging to the 174th Garibaldi Brigade led by Edgardo Alboni, were first tortured and then shot at the firing range on the afternoon of August 22, 1944;[146] later, in the same place it was the turn of six others (Pietro Biancardi, Marcello De Avocatis, Lino Ferrari, Giuseppe Frigoli, Paolo Sigi and Ferdinando Zaninelli).[147] These, remembered as the "Martyrs of the Polygon," were not the only victims of the Lodi Resistance: former mayor Ettore Archinti, after being accused of aiding the escape to Switzerland of some British prisoners, was deported to the Flossenbürg concentration camp, where he died;[148] partisan Rosolino Grignani, a former soccer player for Fanfulla in Serie C, was murdered by retreating Nazis;[149] other massacres of civilians were carried out in Galgagnano and Sant'Angelo,[150] while three antifascists from Castiglione d'Adda were killed in the Crema stadium.[151]

Between the evening of April 25, 1945, and the following morning, the forces under the local CLN - headed by Christian Democrat Giuseppe Arcaini - went on the attack, taking possession of the main public buildings, barracks and other strategic points; a Wehrmacht column about to bombard the city was neutralized by a group of partisans, assisted by ordinary armed citizens.[152] On April 27, the Germans quickly left the town, shooting sixteen young men to death in Viale Piacenza: when the Allies arrived in Lodi two days later, they found it already totally free.[152][153] A few weeks later a provisional administration composed of delegates from all components of the CLN took office: the mayor was the independent Mario Agnelli, who was later succeeded by the Communist Celestino Trabattoni.[154][155]

Lodi between the 20th and 21st centuries

The decades following the birth of the Italian Republic were characterized by a marked demographic increase: the population of the municipality grew from about 30,000 inhabitants in the immediate postwar period to 44,422 residents in the general census conducted in 1971.[85] Beginning in 1955, Lodi likewise experienced an impetuous urban and infrastructural development involving both banks of the Adda River:[85] new neighborhoods sprang up, including that of the "Fanfani houses" (west of the historic center) and the "Oliva village" (southwest), both built under the INA-Casa program.[156] Public life at that time was marked by the difficulty in reaching an agreement on the municipal master plan, which was not approved until March 1970 after nearly a century of fruitless attempts.[157][158]

Meanwhile, in the 1950s the large urban park of Isola Carolina had been opened, created through a donation by Enrico Mattei, who wanted in this way to reward the city near which abundant deposits of natural gas had been discovered;[note 10] the green area, covering approximately 50,000 m² and located close to the historic core of the town, is home to essences of considerable botanical interest, selected at Lake Como and in Tuscany.[159][160][161] Between the 1970s and the 2000s - in addition to the construction of a system of bypass roads, completed in 2001 with the inauguration of the second bridge over the river[162] - the decommissioning of a large part of the industrial building stock took place, converted into new residential or service areas:[163] a prime example of this transformation is the Management Center of the Banca Popolare di Lodi, designed by architect Renzo Piano and built on the site of the former Polenghi Lombardo factories, in the vicinity of the Porta Regale castle.[164]

On March 6, 1992, the province of Lodi was formally established, following the spin-off of 61 municipalities from the province of Milan;[note 11][11] the prefecture and elected bodies were made operational three years later.[165][166] Pope John Paul II stayed briefly in the city on June 20, 1992, becoming the first reigning pontiff to visit the Laudense diocese.[167]

At the beginning of the 21st century - before the great recession - Lodi benefited from considerable economic growth, confirming its status as an important road junction and industrial center in the fields of cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, engineering, plastics processing, handicrafts and dairy production.[168] Activities related to the tertiary sector also developed: in the 2000s, in particular, there was a strong expansion of banking and IT services, as well as cultural and food and wine tourism.[168][169][170]

Moreover, representing the reference point of a territory traditionally devoted to agriculture and livestock breeding, the city was chosen as the headquarters of the Parco Tecnologico Padano; the structure - inaugurated in 2005 by the President of the Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi[171] - established itself among the most qualified research centers at the European level in the field of agrifood biotechnology.[172][173] Since 2018, the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Milan has also been based in Lodi; the teaching buildings, designed by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, are flanked by an experimental zootechnical laboratory and a veterinary hospital.[174]

Like many other centers in northern Italy, the city has become a multiethnic and multicultural reality, marked by a significant presence of inhabitants from abroad: in 2008 foreign residents exceeded 10 percent of the total population for the first time.[175][176]

Notes

- The passage is taken from the work of Otto and Acerbo Morena, handed down under the title De rebus Laudensibus.

- The Contado di Lodi, whose boundaries were marked by the Adda to the east, the Po to the south, the Lambro to the west and the Muzza to the north, was the rural territory immediately subject to the jurisdiction of the municipality; see "Contado di Lodi, sec. XIV - 1757". lombardiabeniculturali.it. January 3, 2006. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- The manuscript, referred to as "Laudensis," was later lost.

- The so-called "treasure of Saint Bassianus" consisted of a rich collection of gold work.

- The term "chiosi," of dialectal origin, indicated the agricultural lands surrounding the city of Lodi, analogous to the better-known Holy Bodies around Milan.

- Lodi had inherited the title of city from Laus Pompeia, an ancient Roman municipium, as attested on December 3, 1158 by an imperial diploma issued by Frederick Barbarossa; the status of "city of the Lombardy-Venetia Kingdom" was recognized by the Imperial Regia Patente of April 24, 1815 (see Meriggi (1987, p. 97)).

- The only de facto capital was Lodi, where all administrative offices were located; the title given to Crema was purely honorary.

- Instead, the area of Crema was united with the province of Cremona.

- D'Annunzio, Gabriele (1912). Laudi del cielo, del mare, della terra e degli eroi. Libro quarto: Merope.

Maremma, canto i tuoi cavalli prodi./ Tra sangue e fuoco ecco un galoppo come/ un nembo. È la Cavalleria di Lodi,/ la schiera della morte. So il tuo nome,/ o buon cavalleggero Mario Sola./ Giovanni Radaelli, so il tuo nome;/ Agide Ghezzi, e il tuo. "Lodi" s'immola./ E veggo i vostri visi di ventenni/ ardere tra l'elmetto ed il sottogola,/ o dentro i crini se il caval s'impenni/ contra il mucchio. Gandolfo, Landolina,/ alla riscossa! Tuona verso Henni./ Tuona da Gargaresch alla salina/ di Mellah, su le dune e le trincere,/ sulle cubbe, su fondachi, a ruina,/ sui pozzi, su le vie carovaniere./ La casa di Giamil ha una cintura/ di fiamma. Appiè, appiè, cavalleggere!

- The main deposit, whose reserves amounted to 12 billion cubic meters, was identified between 1943 and 1944 in the Caviaga area, a hamlet of Cavenago d'Adda, and at the time was the largest in all of Western Europe; see Francesco Guidi; Franco Di Cesare. "Caviaga, a sessant'anni dalla scoperta" (PDF). Associazione pionieri e veterani Eni. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020. For this reason, Lodi was the first city in Italy to use methane for civilian purposes; see "50º anniversario della morte di Enrico Mattei". Comune di Lodi. October 2012. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2020..

- The municipalities in the provincial constituency became 60 in 2018, concurrently with the merger of Camairago and Cavacurta into the new municipality of Castelgerundo (regional law Dec. 11, 2017, n. 29).

References

- Bassi (1977, pp. 15–19).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 15–16).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 17–26).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 17–30).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 30–31).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 37–47).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 55–59).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 59–86).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 100–106).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, p. 3).

- Decreto legislativo 6 marzo 1992, n. 251, articolo 2.

- Pliny the Elder, III, 124.)

- Bassi (1977, p. 15).

- Bassi (1977, p. 20).

- Polybius, II, 32-34).

- Bassi (1977, p. 16).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 17–18).

- Bassi (1977, p. 18).

- Bassi (1977, p. 17).

- Bassi (1977, p. 19).

- Lucian of Samosata, pp. 55, 1).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 18–19).

- Ciseri (1990, pp. 285–286).

- Bassi (1977, p. 23).

- Symmachus, VII, XIII e XIV).

- Sigonio (1574, I, 2, p. 500).

- Bassi (1977, p. 25).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 25–26).

- Bassi (1977, p. 24).

- Bassi (1977, p. 26).

- Vignati (2017, parte I, vol. 1, n. 170, p. 203).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 26–29).

- Bassi (1977, p. 29).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 29–30).

- Bassi (1977, p. 30).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 15).

- Bassi (1977, p. 37).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 16).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 37–38).

- Bassi (1977, p. 38).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 38–41).

- Ambreck (1996, p. 142).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 35).

- Bassi (1977, p. 41).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 41–42).

- Bassi (1977, p. 42).

- Bassi (1977, p. 43).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 43–44).

- Bassi (1977, p. 47).

- Bassi (1977, p. 48).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 42–43).

- Bassi (1977, p. 44).

- Bassi (1977, p. 49).

- Vignati (2017, parte II, vol. 1, n. 335, p. 335; parte II, vol. 2, nn. 342-343, pp. 345-346).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 44–47).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 24).

- Ambreck (1996, p. 134).

- Grillo & Levati (2017, p. 114).

- Bassi (1977, p. 53).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 53–54).

- Bassi (1977, p. 54).

- Bassi (1977, p. 62).

- Scarcia Piacentini, Paola (1983). "La tradizione laudense di Cicerone ed un inesplorato manoscritto della Biblioteca Vaticana (Vat. lat. 3237)". Revue d'histoire des textes. Aubervilliers: Institut de recherche et d'histoire des textes. 11 (1981): 123–146. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Bassi (1977, pp. 54–55).

- Majocchi (2008, pp. 187–286).

- Bassi (1977, p. 55).

- Ambreck (1996, p. 133).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 55–62).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 56–59).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, pp. 22–23).

- Bassi (1977, p. 59).

- Bassi (1977, p. 63).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 59–60).

- Bassi (1977, p. 60).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 60–61).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 64).

- Bassi (1977, p. 61).

- Bassi (1977, p. 69).

- Bassi (1977, p. 70).

- Bassi (1977, p. 72).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 72–75).

- Bassi (1989, p. 265).

- Bassi (1977, p. 78).

- Bassi (1977, p. 75).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 25).

- Bassi (1977, p. 76).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 65).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 61).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, p. 76).

- Agnelli (1989, pp. 243–244).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, pp. 37–39).

- Agnelli (1989, p. 248).

- Bottini, Caretta & Samarati (1979, pp. 24–25).

- Meriggi (2005, p. 113).

- Bassi (1977, p. 83).

- Chandler (2006, pp. 132–136).

- Chandler (2006, p. 137).

- Bassi (1977, p. 84).

- Chandler (2006, p. 138).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 84–85).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 95–96).

- Chandler (2006, p. 139).

- Bassi (1977, p. 85).

- Bassi (1977, p. 86).

- "Comune di Lodi, 1796-1815". lombardiabeniculturali.it. Regione Lombardia. 8 June 2004. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. 1960–2020. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Bassi (1977, pp. 86–89).

- Giovanni Agnelli (September 1904). "Ferdinando I, il Passeggio interno e l'Obelisco del Largo Roma". Archivio storico per la città e comuni del circondario di Lodi. Lodi: Società storica lodigiana. anno 23 (fascicolo 3): 140–144. ISSN 0004-0347. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Bassi (1977, p. 87).

- Bassi (1977, p. 89).

- Bassi (1977, p. 90).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 90–91).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 91–99).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 99–100).

- Bassi (1977, p. 100).

- Bassi (1989, p. 296).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 100–107).

- Bassi (1977, p. 101).

- Meriggi (2005, pp. 114–117).

- Meriggi (2005, pp. 114–132).

- Meriggi (2005, pp. 112–116).

- Bassi (1989, p. 304).

- Bassi (1977, p. 102).

- Regio decreto 18 gennaio 1877, n. 3644.

- Bassi (1977, pp. 102–103).

- Bassi (1977, p. 103).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 103–104).

- Bassi (1977, p. 107).

- Bassi (1977, pp. 108–109).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 56–60).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 60–62).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 62–65).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 65–67).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 64–71).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 71–74).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 42–44).

- Colombo (2005, p. 71).

- Fusari (2005, p. 211).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 71–72).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 6–8).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 13–18).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 27–30).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 69–70).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 36–39).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 50–51).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 57–60).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 101–104).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 75–78).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 21–23).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 50–52).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 85–89).

- Ongaro & Riccadonna (2006, pp. 128–132).

- Colombo (2005, p. 76).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 76–78).

- Bassi (1979, pp. 158–166).

- Meriggi (2005, p. 135).

- Colombo (2005, pp. 78–91).

- Meriggi (2005, p. 144).

- Colombo (2005, p. 88).

- Laura De Benedetti (25 August 2018). "Lodi, parla un dirigente del Comune degli anni '50: "Così nacque l'Isola Carolina"". Il Giorno. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Pubblicato il bando del concorso di progettazione dei lavori di riqualificazione del Parco dell'Isola Carolina (comunicato stampa), Comune di Lodi, 31 agosto 2007.

- "Lodi, nuovo ponte sull'Adda. L'attesa è durata 26 anni". Corriere della Sera. 15 November 2001. p. 53.

- Meriggi (2005, p. 109).

- Galuzzi, sezione 12 – La Lodi moderna.

- "Come raggiungerci". Prefettura - Ufficio Territoriale del Governo di Lodi. 14 April 2009. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Cenni storici". Provincia di Lodi. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Pallavera (2005, pp. 4–5).

- Dossi (2005, entry "Lodi").

- La Provincia di Lodi torna alla BIT (comunicato stampa), Provincia di Lodi, 20 febbraio 2008.

- Federico Gaudenzi (5 October 2017). "La Rassegna fa festa nel segno del gusto". Il Cittadino. p. 4.

- "Ciampi sprona Lodi e l'Italia". Il Cittadino. 8 December 2005. p. 1.

- Caterina Belloni (18 October 2006). "Ricerca, la sfida lombarda: "Ora importiamo cervelli"". Corriere della Sera. p. 13.

- Andrea Caruso (25 March 2013). "Svelato a Lodi il "Dna" del pesco, una storia che ha 4mila anni". Il Cittadino. p. 12.

- "Medicina veterinaria". Università degli Studi di Milano. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Bilancio demografico e popolazione residente straniera al 31 dicembre 2008". Istituto nazionale di statistica. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2020.