History of Winchester College

The history of Winchester College began in 1382 with its foundation by William of Wykeham. He was a former Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor to both Edward III and Richard II. He decided to found the school in response to the lack of trained priests after the Black Death. Winchester was to operate as a feeder or Latin grammar school[1] to New College, also founded by Wykeham.[2]

Winchester College, as with other medieval schools, taught Latin grammar and other subjects through the medium of Latin. Pupils were required to speak Latin as well as read and write it. This practice continued through the early modern period. Latin dominated knowledge production in most subjects before 1650, and was the spoken language of Universities and lectures until the 1700s.[3]

Foundation and early years

The college was set up by Wykeham with a dual religious and educational and purpose.[4] Funds were set aside for chantries, so that prayers would be said for the founder's soul, for instance. Three chaplains, three clerks and sixteen choristers were given an extensive programme of prayers and services to deliver. By contrast, two masters would educate the pupils; ten fellows and the warden would be concerned with both religious and educational aspects. Extensive bequests were made to ensure the longevity of the institution; the 70 scholars were to be maintained through these alongside the staff.[5]

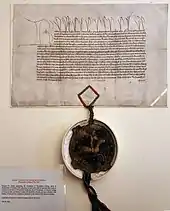

According to its 1382 charter and final statutes (1400), the school is called in Latin Collegium Sanctae Mariae prope Wintoniam ("St Mary's College, near Winchester"), or Collegium Beatae Mariae Wintoniensis prope Winton ("The College of the Blessed Mary of Winchester, near Winchester").[6] New College was also dedicated to St Mary; the naming reflects the school and university's religious affiliations as well as educational purpose. New College would educate Winchester's students in theology and law, also through the medium of Latin.

The first 70 poor scholars entered the school in 1394.[7] Basic proficiency in Latin (having covered the grammar of Donatus) was required for entry,[8] as the majority of pupil's time was to be spent perfecting their Latin grammar. The college operated a Latin-only rule, that is, only Latin was to be spoken 'in hall'. In contrast, schools set up prior to 1350 tended to allow both French and Latin, as both needed practice; this shows that the use of French was no longer as important.[9]

In the early 15th century the specific requirement was that scholars come from families where the income was less than five marks sterling (£3 6s 8d) per annum; in comparison, the contemporary reasonable living for a yeoman was £5 per annum.[10]

Other innovations at Winchester included enforcing discipline through the pupils themselves, using prefects. Discipline was in any case meant to be less harsh than was common in medieval schools, at least as the statutes read.[11] Winchester was also unusual in giving education to boys aged 12–18, as universities would accept students within this age range.[12] These features, including the double foundation, formed the model for Eton College and King's College, Cambridge, some 50 years later.[13] Eton and Winchester formed a close partnership in this period.[14]

At first only a small number of pupils other than scholars were admitted; by the 15th century the school had around 100 pupils in total, nominally the 70 scholars, 16 choirboys known as "quiristers", and the rest "commoners". Demand for places for commoners was high, and though at first restricted, numbers gradually rose.[15]

Early modern period

As the college was a religious as well as educational establishment, it was threatened with closure during Henry VIII's reign. In 1535, a visitation was made to assess the college's assets, after which some of Winchester's valuable land assets near London were seized and exchanged for assets of similar size elsewhere in the country, depriving the college of substantial wealth.[16]

A statute to seize Winchester College's assets, and in effect abolish the school alongside those of several Oxford and other colleges, was drawn up in 1545, which was only halted by Henry's death. Edward VI swiftly reversed direction.[17] Edward made provision for worship and Bible readings to be made in English rather than Latin.[18]

In the early modern period, under Henry, Edward, Elizabeth and James, royal visits were accompanied by presentations of Latin and a small amount of Greek occasional poetry, composed by the pupils. Elizabeth also granted an exemption to allow Winchester, Eton and elsewhere to conduct their religious services in Latin, to help pupils to improve their skills in the language.[19]

Among the school's Latin scholars to make their mark, Christopher Johnson stands out from this period as particularly praised by his contemporaries. As both pupil and later headmaster of the college, his poetry is also important source material for the conditions and daily life of the college in the period. His poem about life as a pupil at Winchester was composed while a student.[20] Practice in writing Latin poetry was a common part of Latin education of the period.[21] An English language poet, lawyer and politician, John Davies, was also educated at the school.

Both Elizabeth and James made use of the school for reasons of state, in different ways. Elizabeth attempted to impose appointments on the schools, not always successfully.[22] James ordered the school to provide accommodation for judges who were to try Sir Walter Raleigh for treason at the town's courts.[23]

The college became involved with disputes with church authorities during James and Charles' reigns. In 1608, Archbishop Bancroft made orders against abuses such as nepotism in the preferment of pupils at the school, and demanded that teachers cease demanding payment from pupils. In 1635 Archbishop William Laud, concerned about the school's Puritan religious leanings, issued orders demanding religious observances at Winchester, such as full performance of services and placement of the altar north–south, at the east end of the chapel.

At the start of the English Civil War, Winchester and the surrounding county was within the Royalist camp. When Parliamentary forces took over the town in autumn 1645, and ransacked many buildings including the cathedral, the school avoided serious damage to its property. The earlier religious disputes with Laud may have helped the school in their dealings with Parliament and its forces.[24]

Victorian era to present

From the 1860s, ten boarding houses, each for up to sixty pupils, were added, greatly increasing the school's capacity.[25] By 2020, the number of pupils had risen to 690.[26] From 2022, the school has accepted day pupils in the Sixth Form, including girls.[27]

References

- Leach 1899, pp. 8, 89, throughout explains that "grammar school" in the medieval period is a general term for a school providing Latin grammar education, rather than the later system set up after the Reformation

- Adams 1878, pp. 19–23

- Leach 1899, p. 164.

- The college articles stated that its purpose waa "ad divini cultus, liberaliumque artium augmentum"; "for the increase of divine worship and the liberal arts" Adams 1878, pp. 42–46

- Adams 1878, pp. 42–46

- Hebron, Malcolm (2019). "The statutes of Winchester College, 1400". In Foster, Richard (ed.). 50 Treasures from Winchester College. SCALA. pp. 9, 45–47, 55. ISBN 978-1785512209.

- "Winchester College: Heritage". Winchester College. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Adams 1878, p. 53

- Leach 1899, p. 165

- Harwood, Winifred A. (2004). "The Household of Winchester College in the later Middle Ages 1400-1560" (PDF). Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club Archaeological Society. 59: 163–179. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Adams 1878, pp. 56–7

- Leach 1899, pp. 159–160

- Clutton-Brock, A. (1900). Eton. George Bell and Sons. pp. 3–5.

- Adams 1878, pp. 65–67

- Turner, David (2014). The Old Boys: the decline and rise of the public school. Yale University Press. pp. 2–9. ISBN 978-0-300-18992-6.

- Adams 1878, pp. 70–71.

- Adams 1878, pp. 70–71.

- Adams 1878, pp. 73–76.

- Adams 1878, p. 77.

- Adams 1878, pp. 82–83.

- Companion to Neo Latin Literature

- Adams 1878, pp. 78–80

- Adams 1878, p. 87

- Adams 1878, p. 89

- "Houses: Why is it so important to belong?". Winchester College. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Winchester College". SchoolSearch.co.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Winchester College: Welcoming girls for the first time". School Management Plus. 14 October 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

Sources

- Adams, Henry C (1878). Wykehamica: A History of Winchester College. Oxford, London and Winchester: James Parker. OL 7595302W.

- Cook, Arthur K; Mathew, Robert (1917). About Winchester College. London: Macmillan.

- Custance, Roger, (ed.), Winchester College: Sixth Centenary Essays, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982

- Dilke, Christopher, Dr Moberly's Mint-Mark: A Study of Winchester College, London: Heinemann, 1965

- Fearon, William A., The Passing of Old Winchester: Winchester: Winchester College, 1924

- Firth, J. D'E., Winchester College, Winchester: Winchester Publications, 1949

- Kirby, T. F., Annals of Winchester College, London and Winchester: Henry Frowde, 1892

- Leach, Arthur F. (1899). A History of Winchester College. London: Duckworth. OL 10622775W.(Review)

- Mansfield, Robert, School Life at Winchester College, London: John Camden Hotten, 1866

- Rich, Edward J. G. H., Recollections of the Two St. Mary Winton Colleges, Walsall and London: Edward Rich, 1883

- Sabben-Clare, James (1981). Winchester College. Paul Cave Publications.

- Stevens, Charles, Winchester Notions: The English Dialect of Winchester College, London: Athlone Press, 1998

- Tuckwell, William, The Ancient Ways: Winchester Fifty Years Ago, London: Macmillan, 1893

- Townsend Warner, Robert (1900). Winchester. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Walcott, Mackenzie E. C., William of Wykeham and his Colleges, London: David Nutt, 1852

- Wordsworth, Charles, The College of St Mary Winton near Winchester, Oxford and London: J. H. Parker, 1848