Notions (Winchester College)

Winchester College Notions are the specialised terms, and sometimes customs, that have been used by pupils, known as men, at Winchester College.[2] Some are specific to the school; others are survivals of slang or dialect that were once in wider usage. Notions tests were formerly held in each house of the school, and numerous manuscript and printed books were written to collect notions for pupils to learn. Some notions were customs, such as the Morning Hills assembly held on top of St. Catherine's Hill; others were humorous, like the Pempe, a practical joke played on new pupils. Most notions have now fallen into disuse.

Definition

A notion is "any word, custom, person or place peculiarly known to Wykehamists", pupils of Winchester College.[2] The notions in use have continually changed; even in 1891, the Old Wykehamist Robert Wrench noted that some had vanished through neglect or had become obsolete as circumstances had changed.[3] The earliest notions book, circa 1840, contained some 350 notions; around 1000 current and obsolete notions were listed by 1900.[4] Most of these fell into disuse in the 20th century, so that by 1980, the number of notions in use was according to the former headmaster of Winchester College James Sabben-Clare "really quite small".[5]

Notions books

Notions were traditionally recorded in manuscript books for the use of new men, pupils joining the school.[6][3] Many old examples of such manuscript notions books are preserved by Winchester College.[1] Among them are books by R. Gordon (1842); F. Fane (1843); Thomson (c. 1855); J. A. Fort (1874); A. L. Royds (1867); and A. H. S. Cripps (1868–72). Printed versions are Wrench's Word Book[7] and Three Beetleites.[8] The latter was long considered authoritative.[1]

The fullest book of College notions (as opposed to Commoners notions) is that by Charles Stevens. This book is unusual in that it reflects the usages of the 1920s, when the author was at school, but was continually revised by the author from a scholarly point of view and typed out in the 1960s. It was edited by Christopher Stray and printed in 1998.[9][1] Other manuscript books are those of Steadman (1955), Foster (c. 1969), Tabbush (1973–4) and Gay (1974). These were generally kept by whatever senior man was most interested in notions, and circulated shortly before Notions Examinā in each year. In the late 1980s this was formalized, and the custodian was known as "Keeper of the Notions and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sutton Scotney".

A slim brochure, containing only the most basic notions in common use, is printed by P & G Wells and used to be distributed to new men.[10] In earlier times this was available for sale, but was confined to Commoner notions (as recorded in Three Beetleites) and never seen in College.

Etymologies

Winchester-specific

Winchester College notions are not all specific to the school, but have a variety of origins. Clearly specific are some of the names of places or objects inside the school, such as "Gunner's Hole" for the old swimming-place on the river,[11] or "Moab" for the washing-place in College, from the passage in Psalm 60 "Moab is my wash-pot".[12]

There are, too, some quite specific notions based on school customs. "College Men" are pupils with scholarships, living in the school's medieval buildings, while "Commoners" are all the rest. For his first few weeks as a "Jun Man" (junior pupil), a Commoner has a Tégé (pronounced and sometimes written "Teejay") while a College Man has a Pater (Latin for "father"): a Middle Part (second year) Man appointed to look after his "Protégé" (from French) or, in College, "Filius" (Latin for "son").[13] A Toys is the upright wooden stall with a seat and cupboard where a pupil works and keeps his books; it is said to derive from Old French toise, "fathom", for the original width of a Toys. From this comes Toytime, evening homework or prep.[14]

Shared

A few notions have historically been shared with other schools: for instance Eton once used words like "div" (class or form[lower-alpha 1])[15] and "poser" (examiner, as used in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer),[16] and Radley uses "don" for teacher.[17][18] Some are common words used in a particular sense, like Man, which at Winchester means a pupil of any age.[19] Other are derived from common usages, such as "to mug up" which has a dictionary meaning of "to study intensively";[20] the notion to mug just means "to work"; hence Mugging Hall, the room in every house (not including College) surrounded by rows of Toys cubicles where pupils work. To mug also means to bestow pains upon (something),[21] like "to muzz" at Westminster School.[22]

The importance given to notions at Winchester caused them to be recorded carefully over a long period, so that compared to schools like Westminster or Eton which had similarly rich and old traditions, Winchester's notions are now uniquely accessible to scholars, who have begun to examine them both as words and as the customs of "an institution notoriously eccentric even within living memory and almost unimaginably so before the reforms of 1867".[23]

Vowel-modifications

Many notions were formed by vowel-modification, a widespread practice in the 19th century; thus "crockets" is the notion for the playground game of French cricket,[3] while "Bogle" or "bogwheel" is a modification of "bicycle".[24]

Slang and dialect

Other forms derive from slang, such as "ekker" (exercise), using the common speech ending "-er"; others again were once dialectal forms, such as "brum" for penniless, from Kentish dialect "brumpt" (bankrupt).[4] Wrench suggests that Lob[ster] for "to cry" may come from Hampshire dialect "louster", to make an unpleasant noise.[25]

Survivals from Latin, Old English and Middle English

Some notions, such as foricas (toilet) and licet/non-licet (permissible/forbidden) are straightforwardly Latin terms.[4]

A few are derived from Old English: brock (to bully) is ultimately from Old English broc, badger, which Three Beetleites suggests survived by way of northern dialect "brock" (badger) and the bullying sport of badger-baiting.[26] Swink (to work hard) is a survival from Old English swincan (Middle English swynke), with the same meaning,[27] while Cud, meaning pretty, derives ultimately from Old English cuð, via northern dialect "couth" or "cooth".[28]

Other notions are from Middle English: a scob, a type of chest used as a desk in College, is a Middle English word derived from Latin scabellum, French Escabeau,[29] while thoke (a rest, an idle time[13]), meant "soft, flabby" in the 15th century.[30][31]

Abbreviations

Several notions were created by abbreviating words, as in Div (from "Division of the School"), for class or form.[13] Such notions could be assembled into phrases – for example, the Dons' Common Room Notice Board became Do Co Ro No Bo.[4] Abbreviations are often indicated by a colon, as in 18th-century handwriting, for example "Sen: Co: Prae:" (Senior Commoner Prefect); some end with a long vowel, indicated with a macron, for example "competī", "mathmā" and "examinā" (for "competition", "mathematics", and "examinations" respectively).[4][32] There were slight differences of vocabulary between College Men and Commoners.[33]

Folk etymologies

Some notions acquired a folk etymology:

- Remedy and Half-remedy (usually shortened to rem and half-rem), meaning a day or a half-day holiday respectively, was formerly supposed to be derived from dies remissionis (holiday), anglicised as "remi day". Its actual origin is Latin remedium, rest or refreshment.[34]

- Firk, to expel, is derived straightforwardly from Old English fercian, via Middle English fferke. A folk etymology from Latin furca, "[pitch]fork", gave rise to a legend that expelled pupils had their clothes handed to them through the gate by Old Mill on a pitchfork.[35]

As customs

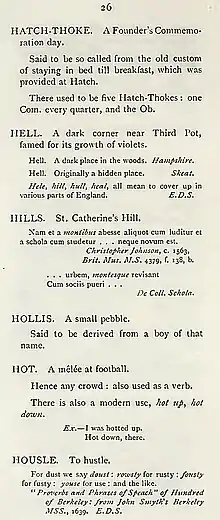

.jpg.webp)

An example of a custom which is a notion is Morning Hills, when the whole school gets up early in the morning, once a year, to meet on the top of St. Catherine's Hill, a nearby hill belonging to the college.[36] It used to be the only time that the whole school regularly assembles together; a former headmaster, James Sabben-Clare, wrote that each year, the head explained this fact "to disbelieving parents of first-year boys".[37]

A "bad notion" was a custom that was not permitted to pupils in a certain group; for instance, in 1901 it was a bad notion for a pupil who had been at the school for less than four years to wear a speckled straw hat.[32]

Notions tests

Annual event

Notions examinā, or latterly just "Notions", used to be an annual event in each house, including College.[38] It was held after the first two weeks of the autumn term, and was designed to test new boys' familiarity with the manners and customs of the school.[3][39] In College, it was accompanied by feasting and a ritual list of absurd formulaic questions and answers, such as[38]

Which way does College clock face?

Into Mrs. Bendle's boudoir.[38]

Sabben-Clare writes that the clock has no face, and doubts whether the odd-job man's wife had a boudoir.[38]

The "Tunding Row"

In 1872, under the headmaster George Ridding, "tunding", beatings given by a prefect (a senior pupil), using a ground-ash across the shoulders, were still permitted. The matter became a national scandal, known as "the Tunding Row", when "an overzealous Senior Commoner Prefect, J.D. Whyte,"[40] beat the senior boy of Turner's house, William Macpherson, for refusing to attend a notions test. He received "thirty cuts of a ground-ash inflicted on his back and shoulders".[40] Ridding made matters worse by trying to defend the action; the public came to understand that both the housemaster and the headmaster knew and approved of the action. The result was public outrage. Ridding "less than whole-hearted[ly]"[40] limited the prefects' power to beat to twelve cuts, to be administered only on the back.[40] Notions tests were forbidden as a "disgraceful innovation".[41] The Dictionary of National Biography wrote in 1912 that "The incident was trivial, but the victim's father appealed to The Times, and an animated, though in general ill-informed, correspondence followed."[42] Two governors resigned.[42] The notions test however persisted, but more gently and more informally.[38]

The Pempe

The Pempe was formerly a practical joke perpetrated in Commoners. A junior boy was asked to obtain a book called Pempe ton moron proteron (Ancient Greek: Πέμπε τον μωρών προτέρων, 'Send the fool further'); each person he asked for it would refer him to someone else, often in a different house, until someone took pity on him.[43] A similar joke, involving an "important letter" with the words "send the fool further", was practised in Ireland on April Fools' Day.[44]

The College man and natural historian Frank Buckland described his own Pempe experience of 1839:[45]

So he sent me to another boy, who said he had lent his Pempe moron proteron, but he passed me on to a third, he on to a fourth: so I was running about all over the college till quite late, in a most terrible panic of mind, till at last a good-natured præfect said 'Construe it [from Greek], you little fool.' I had never thought of this before. I saw it directly: Pempe (send) moron (a fool) proteron (further)."[45]

By tradition, a notions book should not define a Pempe beyond calling it "A necessity for all new men".[46]

Notes

- At Winchester, the "div" is the form to which pupils belong, and where for instance scientists are taught unexamined humanities by their "div don" (form teacher), as opposed to their French or Mathematics classes where they are taught by specialist teachers in those subjects.

References

- Sabben-Clare 1981, p. 146.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 84 and passim

- "Winchester Notions". The Spectator. 11 July 1891. p. 23. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, pp. 146–148.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, pp. 150–151.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, pp. 144–146.

- Wrench 1891, pp. 1ff.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 1ff.

- Stevens & Stray 1998, pp. 1ff.

- Winchester College: Notions. Winchester: P. & G. Wells. c. 1967. p. 1ff.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 52.

- Bompas 1888, p. 24.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 121–122.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 125–127.

- "July: Public School Slang". The English Project. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Wrench 1891, pp. 40–41.

- "Public School Slang". Holland Park Tuition and Education. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 37.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 73.

- "mug up: verb". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 81–83.

- Partridge, Eric (2003). The Routledge Dictionary of Historical Slang. Routledge. p. 3479. ISBN 978-1-135-79542-9.

- Jacobs, Nicolas (February 2000). "Review: [Untitled] Reviewed Work: Winchester Notions: The English Vocabulary of Winchester College by Charles Stevens, Christopher Stray". The Review of English Studies. 51 (201): 96–98. doi:10.1093/res/51.201.96.

- Partridge, Eric (1984) [1937]. "Cambridge undergraduate slang 1924-40". Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (8th ed.).

- Wrench 1891, p. 32.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 14.

- Le Gallienne, Richard (1900). Travels in England. Chapter 4: Hindhead to Winchester. "Wykehamist 'notions'": Grant Richards. pp. 90–91.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Wrench 1891, p. 18.

- Wrench 1891, p. 49.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, p. 146, which however calls it "Anglo-Saxon"..

- "thoke adj". Middle English Compendium. University of Michigan Library. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 140–141.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 24–27.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 99.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 44.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, pp. 55–57.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, p. 151.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, p. 150.

- Old Wykehamists 1893, p. 115.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, pp. 44–45.

- Gwyn 1982, pp. 431–477

- Kenyon, Frederic George. "Ridding, George", Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement, Volume 3.

- Sabben-Clare 1981, p. 144.

- Johnson, Helen (1 April 2020). "Why do we celebrate April Fools' Day? The history and traditions behind the pranks". The Scotsman. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Bompas 1888, p. 12.

- Lawson, Hope & Cripps 1901, p. 90.

Sources

- Notions books

- Lawson, W. H.; Hope, J. R.; Cripps, A. H. S. (1901). Winchester College Notions, by Three Beetleites. P. and G. Wells. OCLC 903325122.

- Stevens, Charles; Stray, Christopher (1998). Winchester Notions: The English Dialect of Winchester College. Athlone Press. ISBN 0-485-11525-5.

- Wrench, Robert George K. (1891). Winchester Word Book: a Collection of Past and Present Notions. P. and G. Wells. OCLC 315248619.

- History

- Bompas, George C. (1888). Life of Frank Buckland. Smith, Elder, & Co.

- Gwyn, Peter (1982). "The Tunding Row". In Custance, Roger (ed.). Winchester College: Sixth Centenary Essays. Oxford University Press. pp. 431–478. ISBN 978-0199201037.

- Old Wykehamists (1893). Winchester College 1393-1893. Edward Arnold.

- Sabben-Clare, James P. (1981). Winchester College : after 600 years, 1382-1982. Paul Cave Publications. ISBN 0-86146-023-5. OCLC 10919156.