History of opera

The history of opera has a relatively short duration within the context of the history of music in general: it appeared in 1597, when the first opera, Dafne, by Jacopo Peri, was created. Since then it has developed parallel to the various musical currents that have followed one another over time up to the present day, generally linked to the current concept of classical music.

Opera (from the Latin opera, plural of opus, "work") is a musical genre that combines symphonic music, usually performed by an orchestra, and a written dramatic text—expressed in the form of a libretto—interpreted vocally by singers of different tessitura: tenor, baritone, and bass for the male register, and soprano, mezzo-soprano, and contralto for the female, in addition to the so-called white voices (those of children) or in falsetto (castrato, countertenor). Generally, the musical work contains overtures, interludes and musical accompaniments, while the sung part can be in choir or solo, duet, trio, or various combinations, in different structures such as recitative or aria. There are various genres, such as classical opera, chamber opera, operetta, musical, singspiel, and zarzuela.[1] On the other hand, as in theater, there is dramatic opera (opera seria) and comic opera (opera buffa), as well as a hybrid between the two: the dramma giocoso.[2]

As a multidisciplinary genre, opera brings together music, singing, dance, theater, scenography, performance, costumes, makeup, hairdressing, and other artistic disciplines. It is therefore a work of collective creation, which essentially starts from a librettist and a composer, and where the vocal performers have a primordial role, but where the musicians and the conductor, the dancers, the creators of the sets and costumes, and many other figures are equally essential. On the other hand, it is a social event, so it has no reason to exist without an audience to witness the show. For this very reason, it has been over time a reflection of the various currents of thought, political and philosophical, religious and moral, aesthetic and cultural, peculiar to the society where the plays were produced.[3]

Opera was born at the end of the 16th century, as an initiative of a circle of scholars (the Florentine Camerata) who, discovering that Ancient Greek theater was sung, had the idea of setting dramatic texts to music. Thus, Jacopo Peri created Dafne (1597), followed by Euridice (1600), by the same author. In 1607, Claudio Monteverdi composed La favola d'Orfeo, where he added a musical introduction that he called sinfonia, and divided the sung parts into arias, giving structure to the modern opera.

The subsequent evolution of opera has run parallel to the various musical currents that have followed one another over time: between the 17th century and the first half of the 18th it was framed by the Baroque, a period in which cultured music was reserved for the social elites, but which produced new and rich musical forms, and which saw the establishment of a language of its own for opera, which was gaining richness and complexity not only in compositional and vocal methods but also in theatrical and scenographic production. The second half of the 18th century saw the Classicism, a period of great creativity marked by the serenity and harmony of its compositions, with great figures such as Mozart and Beethoven. The 19th century was marked by the Romanticism, characterized by the individuality of the composer, already considered an enlightened genius and increasingly revered, as were the greatest vocal figures of singing, who became stars in a society where the bourgeoisie relegated the aristocracy in social preeminence. This century saw the emergence of the musical variants of numerous nations with hardly any musical tradition until then, in what came to be called musical nationalism. The century closed with currents such as French impressionism and Italian verismo. In the 20th century opera, like the rest of music and the arts in general, entered the avant-garde, a new way of conceiving artistic creation in which new compositional methods and techniques emerged, which were expressed in a great variety of styles, at a time of greater diffusion of the media that allowed reaching a wider audience through various channels, not only in person (radio, television), and in which the wide musical repertoire of previous periods was still valued, which remained in force in the main opera houses of the world.

During the course of history, within opera there have been differences of opinion as to which of its components was more important, the music or the text, or even whether the importance lay in the singing and virtuosity of the performers, a phenomenon that gave rise to bel canto and to the appearance of figures such as the diva or prima donna. From its beginnings until the consolidation of classicism, the text enjoyed greater importance, always linked to the visual spectacle, the lavish decorations and the complex baroque scenographies; Claudio Monteverdi said in this respect: "the word must be decisive, it must direct the harmony, not serve it." However, since the reform carried out by Gluck and the appearance of great geniuses such as Mozart, music as the main component of opera became more and more important. Mozart himself once commented: "poetry must be the obedient servant of music". Other authors, such as Richard Wagner, sought to bring together all the arts in a single creation, which he called "total work of art" (Gesamtkunstwerk).[4]

Background

Opera has its roots in the various forms of sung or musical theater that have been produced throughout history all over the world. Dramatic representation as well as singing, music, dance and other artistic manifestations are forms of expression consubstantial to human beings, practiced since prehistoric times. In Ancient Greece, the theater was one of the favorite spectacles of society. There, the main dramatic genres (comedy and tragedy) were born and the foundations of scenography and interpretation were laid. From various testimonies, it is known that the dramatic representations were sung and accompanied by music, although nowadays hardly any traces of Greek music are preserved. The main playwrights of the time, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, laid the foundations of dramatic art, whose influence continues to this day.[6]

During the Middle Ages, music and theater were also closely related. They were works of religious character, of two types: liturgical dramas to be performed in the churches, celebrated in Latin; and the so-called "mystery play", theatrical pieces of popular character that were represented in the porches of the churches, in vernacular language. These plays alternated spoken and sung parts, generally in choir, and were accompanied by instrumental music and, sometimes, popular dances.[7]

In Japan, the nō theater emerged in medieval times, a type of lyrical-musical drama in prose or verse, with a historical or mythological theme. The narration was recited by a choir, while the main actors performed gesturally, in rhythmic movements. The representation was performed by three actors, together with a choir of eight singers, a flute player and three drummers.[8] In China, the so-called Chinese opera was developed, a type of sung theater, of ritual character, where the music does not accompany the text, but serves only to create atmosphere.[9]

In the Renaissance, several musical-vocal genres emerged, such as the madrigal, oratorio, intermedio, and ballet de cour, which paved the way for the birth of opera. The most immediate was the intermedio (Italian: intermezzo), interludes that were interspersed between the various acts of a theatrical work, which brought together song, dance, instrumental music and scenographic effects, with plots based on Greco-Roman mythology, allegories or pastoral scenes. Its main production center was the Medici Florence, where opera was born shortly afterwards.[10]

Origins

At the end of the 16th century, in Florence, a circle of scholars sponsored by Count Giovanni de' Bardi created a society called Florentine Camerata, aimed to study and critical discussion of the arts, especially drama and music.[11] One of its scholars was Vincenzo Galilei —father of the scientist Galileo— a celebrated Hellenist and musicologist, author of a method of tablature for lute and composer of madrigals and recitatives.[12] In the course of their studies of Ancient Greek theater they found that in Greek theatrical performances the text was sung to individual voices. This idea struck them, since nothing like it existed at the time, at a time when almost all sung music was choral (polyphony) and, in cases of individual voices, occurred only in the religious sphere. They then had the idea of setting dramatic texts of a profane nature to music, which germinated in opera (opera in musica was the name given to it by the Camerata).[13][note 1] Galilei was the main advocate of a single melodic line —the monody— as opposed to polyphony, which he considered to generate an incoherent musical discourse, a theory he expounded in Dialogo della musica antica et della moderna (1581). Another of the Camerata's scholars, Girolamo Mei, who was the one who mainly investigated Greek theater, pointed out the emotional affect that individual singing generated in the audience in Greek theatrical performances (De modis musicis antiquorum, 1573).[14]

Thus, one of the members of the Camerata, the composer Jacopo Peri, created Dafne (1597),[15] with libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini, based on the myth of Apollo and Dafne, with a prologue and six scenes; of this work only the libretto and small fragments of the music are preserved. Peri, who was also a singer, represented Apollo. This was followed, in 1600, by Euridice —by the same authors— the first surviving complete opera, on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. It was composed on the occasion of the wedding between Henry IV of France and Maria de Medici, celebrated in Florence in 1600. Peri played Orpheus.[16]

Another member of the Camerata, Giulio Caccini, composed in 1602 Euridice, with the same libretto by Rinuccini as his namesake of two years earlier, with prologue and three acts.[17] He was the author of the first theoretical treatise on the new genre, Le nuove musiche (1602).[18] His daughter, Francesca Caccini, was a singer and composer, the first woman to compose an opera: La liberazione di Ruggiero dall'isola d'Alcina (1625).[19]

One of the main novelties of this new form of artistic expression was its secularism, at a time when artistic and musical production was mostly of a religious nature. Another was the appearance of monody, the singing of a single voice, as opposed to medieval and Renaissance polyphony; it was a vocal line accompanied by a basso continuo of harpsichord or lute.[20][note 2] Thus, the first operas had parts sung by soloists and parts spoken or declaimed in monody, known as stile rappresentativo.[12]

These first experiences were a great success, especially among the nobility: the Medici became patrons of these performances and, from Florence, they spread to the rest of Italy. The House of Gonzaga of Mantua then commissioned the famous madrigal composer Claudio Monteverdi to write an opera: La favola d'Orfeo in 1607, with libretto by Alessandro Striggio, an ambitious work composed for orchestra of forty-three instruments —including two organs—[21] with prologue and five acts. In this work, libretti were printed for the first time so that the audience could follow the performance.[22] Monteverdi added a musical introduction which he called "symphony", and divided the sung parts into "arias", giving structure to modern opera.[23] These arias alternated with the recitative, a musical line that included spoken and sung parts.[24] He also introduced the ritornello, an instrumental stanza repeated between the five acts.[24] As for the voices, although he left some parts in polyphony, he differentiated the main solo voices: Orpheus was tenor, Eurydice soprano, and Charon bass.[21] In 1608, Monteverdi premiered L'Arianna, with libretto by Rinuccini, of which the music has not been preserved, except for one fragment: the Lamento d'Arianna.[21]

During the first decades of the 17th century the opera gradually spread: in 1608 was premiered in Mantua La Dafne, again with Rinuccini's libretto, this time set to music by Marco da Gagliano.[25] In Rome, Rappresentazione di anima e di corpo, by Emilio de' Cavalieri, a melodramma spirituale that is often considered a precedent of opera, was premiered in 1600, and which pointed out some of the variants of Roman opera as opposed to Florentine opera: greater presence of sacred themes, the presence of allegorical characters, and greater use of choirs.[26] Pope Paul V and the Barberini family sponsored the new genre: the Barberini built an auditorium for 3000 people in their palace.[27] They also promoted the creation of a school of operatists, among whom Stefano Landi, author of La morte d'Orfeo (1619), which as a novelty introduced comic elements. Religious themes were also introduced, as in Il Sant'Alessio (1631), by Landi, with libretto by cardinal Giulio Rospigliosi (future pope Clement IX). In this work, Landi introduced the fast-slow-fast structure —called Italian overture— which would be widely used ever since.[27]

Another introducer of the monodic style in Rome was Paolo Quagliati, who adapted old madrigals of his in opera form: Il carro di fedeltà d'amore (1606), La sfera armoniosa (1623).[28] In the Roman school also stood out Luigi Rossi, who worked for the Barberini. In 1642 he premiered in their theater Il palazzo incantato, a sumptuous production that was a great success. When in 1644 the Barberini had to go into exile in Paris, Rossi accompanied them, and obtained the protection of Cardinal Mazarin, thus helping to introduce opera in France. There he composed his Orfeo (1647), with prologue and three acts, a large production that featured numerous visual effects.[29] Mention should also be made of Domenico Mazzocchi, impresario as well as composer, who initiated the hiring of singers for opera. He was the author of La catena d'Adone (1626).[30] Another exponent was Michelangelo Rossi (Erminia sul Giordano, 1633; Andromeda, 1638).[31]

In Rome it premiered in 1639 Chi soffre, speri, by Virgilio Mazzocchi and Marco Marazzoli, considered the first comic opera.[32]

In these first works one of the first opera singers of recognized talent stood out vocally: Francesco Rasi, a tenor who was already famous before the rise of opera, who participated in the first performances of Peri's Euridice. In 1598 he entered the service of the Gonzaga of Mantua, for which he performed in this city Monteverdi's Orfeo in 1607; the following year he participated in Gagliano's Dafne. He was also a composer, author of Cibele ed Ati (1617), whose music has been lost.[19]

Baroque

The Baroque[note 3] it developed during the 17th century. It was a time of great disputes in the political and religious fields, in which a division emerged between the Catholic Counter-Reformationist countries, where the absolutist state was entrenched, and the Protestant countries, of a more parliamentary sign.[33]

Baroque music was generally characterized by contrast, violent chords, moving volumes, exaggerated ornamentation, varied and contrasted structure. Despite this, not all baroque music is exaggerated: Bach is an author of harmonic balance, Vivaldi creates simple and radiant melodies. The basis of baroque music is serene and balanced, with ornamentation: arpeggios, mordents, tremolos, sonorous arabesques that are the salt of the baroque musician. It was also at this time that the tempos were introduced to regulate the speed of interpretation: long, adagio, andante, allegro and presto; or the intensity: forte and piano.

During this period, the main musical centers were in the monarchic courts, aristocratic circles and episcopal sees. The instrumentation reached heights of great perfection, especially in the violin[34] The Baroque orchestra was small, usually only a chamber orchestra, or about forty instruments at most. Most were string instruments, plus some oboes, flutes, bassoons and trumpets. Alongside these was a section for basso continuo, usually composed of one or two harpsichords with accompaniment by cello, double bass, lute, viola or theorbo.[35]

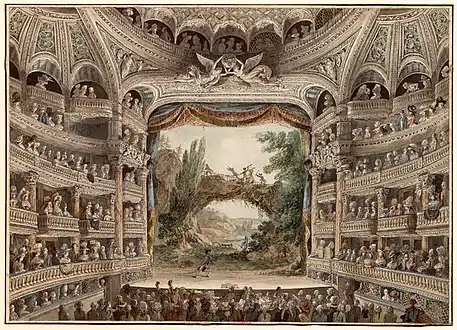

Baroque opera was noted for its complicated and ornate scenography, with sudden changes and complicated lighting and sensory effects. Numerous sets were used, up to fifteen or twenty changes of scenery per performance.[36] There began a taste for solo voices, mainly treble (tenor, soprano), which led in parallel to the phenomenon of the castrati. The latter were children who excelled in singing and who were castrated before entering puberty so that their voice would not change; thus, as adults they maintained a high-pitched voice, close to the female one, but more powerful, flexible and penetrating.[22][note 4] Singing in vibrato was also introduced, consisting of fluctuations in timbre, pitch and intensity, which provided greater emotionality to the interpretation.[37]

In the first half of the 17th century, the rules of operatic librettos were established, which would undergo few variations until almost the 20th century: simple dialogues and conventional language, stanzas of rigorous forms, distinction between "recitative" —declaimed parts that develop the action — and "number" (or "closed piece") — ornamental parts in the form of aria, duet, choir, or other formats.

Venetian opera

In the middle decades of the 17th century the major opera-producing center was Venice, the first place where music was detached from religious or aristocratic protection to be performed in public places: in 1637 the Teatro San Cassiano was founded (demolished in 1812), the first opera center in the world, located in a palace that belonged to the Tron family.[38] The first opera performed was L'Andromeda, by Francesco Mannelli.[39] The theater was founded by Domenico Mazzocchi, who after losing papal favor moved from Rome to the Venetian city.[32][40] As opera became a business, it began to depend more and more on the tastes of the public, since by its attendance at performances it could favor a certain compositional line or relegate it to oblivion.[41] One of the first consequences was that the public showed more and more taste for high-pitched voices, those of tenors, sopranos and castrati, while the use of choirs and large orchestras declined, since an accompaniment of few instruments was preferred, between ten and fifteen, generally. As the genre became more popular, more comic elements were introduced and the texts were simplified, to the point where, especially in the arias, the interpretation was more important than the words that were expressed.[42] After the San Cassiano, the opening of new theaters flourished in Venice: San Giovanni e Paolo (1639), San Moisè (1640), Novissimo (1641), San Samuele (1655) and Santi Apostoli (1649).[39] It was in these theaters that the piazza-like layout surrounded by boxes, typical of opera houses, began.[43]

In Venice the concept of bel canto emerged, which became popular especially in the first half of the 18th century and again in the first half of the 19th century in Italy. It is a vocal technique of difficult execution consisting of maintaining a uniform tone passing from one musical phrase to another without pauses, in a sustained legato that requires a powerful timbre and harmonic articulation. The main interpreters of bel canto were the castrati and the prima donna sopranos.[44] On the other hand, at this time emerged the arioso, an intermediate song between the recitative and the aria, which over time became closed numbers with a tendency to ornamentation.[45] Likewise, from the years 1630–1640 the ensemble, the conjunction of voices in different numbers, was gaining relevance: duet, trio, quartet, quintet, sextet, septet and octet.[46]

The Venetian opera was particularly influenced by the Spanish theater of the so-called Golden Age —especially Lope de Vega— perceptible in the plot confluence between fantasy and reality —a path started with Don Quixote by Cervantes— the abandonment of the Aristotelian units, the coexistence of comic and tragic characters, the relationships between lords and servants, the taste for entanglement and for disguises and cross-dressed characters. In the Venetian operatic milieu these features were called all'usanza spagnuola.[45]

Claudio Monteverdi settled in 1613 in Venice, where he was maestro di cappella of the St. Mark's Basilica.[23] There he composed twelve operas, the principal of which are Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (1640) and L'incoronazione di Poppea (1642).[21] The latter is considered his best opera, with libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello, based on works by Tacitus and Suetonius. It was one of the first operas with a historical rather than a mythological plot.[47]

One of his disciples, Pier Francesco Cavalli, introduced some novelties, such as the use of short arias, in works like L'Egisto (1643), La Calisto (1651), Statira principessa di Persia (1656) and Ercole amante (1662). He was director of the Teatro San Cassiano, with a contract to write one opera a year.[36] Another exponent was Marc'Antonio Cesti, who still further reduced the orchestra, as in Orontea (1649) and Cesare amante (1651). He performed some operas for the emperor Leopold I (Il pomo d'oro, 1668), thus introducing opera into the Germanic sphere.[48] Antonio Sartorio was for ten years maestro di cappella at the ducal court of Brunswick-Lüneburg, until he returned to his native city and was appointed maestro di cappella of St. Mark's Basilica. He is remembered as the introducer of the musical parliament. His major work was Orfeo (1672), which reaped great success.[29] Giovanni Legrenzi was director of the Ospedale dei Mendicanti in Venice and maestro di cappella of St. Mark's Basilica. He composed fourteen operas for various Venetian theaters, many of which have been lost. He introduced the heroic-comic genre, as in his operas Totila (1677), Giustino (1683) and I due Cesari (1683).[49] Pietro Andrea Ziani started in religious music, which he abandoned to devote himself to opera. He succeeded Cavalli as organist of San Marco. His most important works were L'Antigona delusa da Alceste (1660) and La Circe (1665). His nephew, Marco Antonio Ziani, was also an operist in Naples and Vienna.[50]

In the vocal field, Anna Renzi, the first soprano to achieve the status of prima donna, stood out. She played Octavia, wife of Nero, in Monteverdi's L'incoronazione di Poppea.[19] The castrato Siface was also popular with the public, and counted among his admirers Christina of Sweden and Henry Purcell.[19]

French opera

One of the first countries where opera was introduced after Italy was France, where it was called tragédie en musique.[51] In 1645, the first Italian opera, the pastoral La finta pazza, by Francesco Sacrati, was performed in Paris.[52] Two years later Luigi Rossi's Orfeo was performed, which caused a great sensation.[53] Pier Francesco Cavalli premiered his Ercole amante in Paris in 1662, at the newly opened Tuileries Palace a commission of Cardinal Mazarin for the celebration of the wedding of Louis XIV with Maria Theresa of Austria. The work was not much liked, as it was in Italian and with castrati, a strange phenomenon for the French public, more fond of ballets de cour.[54]

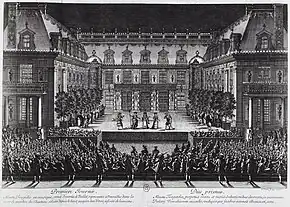

In 1669, the poet Pierre Perrin and the composer Robert Cambert created a company to perform operas in the French taste and obtained from King Louis XIV the royal privilege to constitute an academy, the Académie Royale de Musique, located in the Jeu de Paume de la Bouteille theater. Both authors produced the opera Pomone, the first written in French, premiered in 1671.[13] However, the following year, Perrin was imprisoned for debt and the royal privilege passed to Jean-Baptiste Lully, a composer of Florentine origin (his real name was Giovanni Battista Lulli).[55] Lully adapted opera to French taste, with choirs, ballets, a richer orchestra, musical interludes and shorter arias.[56] He developed French overture[13] in a slow-fast-slow structure, unlike the Italian, which became almost autonomous pieces of the operatic ensemble.[57] On the other hand, he used to accompany the recitative with a harpsichord continuo bass.[58] At the same time, he gave greater prominence to the text, which provided greater expressiveness to the opera.[59] Likewise, he adapted the singing to the prosody of the French language, creating a typically Gallic vocality called déclamation mélodique.[60] From 1673 until 1687, the date of his death, he composed one opera per year-most with libretti by Philippe Quinault-among them: Cadmus et Hermione (1673), Alceste (1674), Atys (1676), Proserpine (1680), Persée (1682), Phaëton(1683), Amadis (1684), Armide (1686) and Acis et Galatée (1686). The most successful was Alceste, based on a tragedy by Euripides and composed to celebrate the victory of Louis XIV in the Franche-Comté, which included a minor plot with a comic air and some catchy melodies that greatly pleased the public.[61]

Another exponent was Marc-Antoine Charpentier, who musicalized some plays by Molière (Le mariage forcé, 1672; Le malade imaginaire [Le malade imaginaire], 1673) and composed several plays for the Comédie-Française, such as Les amours de Vénus et d'Adonis (1678), David et Jonathas (1688) and La noce du village (1692). His masterpiece is the tragedy Médée(Medea, 1693), on a play by Pierre Corneille.[62]

Marin Marais was a composer and performer of viola da gamba. He worked at the court of Louis XIV and was conductor of the orchestra of the Académie Royale de Musique. He composed four Lullian-style operas: Alcide (1693), Ariane et Bacchus (1695), Alcyone (1706) and Sémélé (1709).[16]

After Lully's operas, and because of the French fondness for ballet, there arose the opera-ballet, a hybrid genre of the two, in which sung parts with music alternated with danced interludes, with generally comic and amorous themes. This genre was introduced by André Campra with L'Europe galante (1689), which was followed by numerous works by this author, most notably Les fêtes vénitiennes (1710).[13] Campra also produced conventional operas, such as Tancrède (1702) and Idoménée (1712).[63]

Development in Europe

Throughout the seventeenth century opera spread throughout Europe, generally under Italian influence. In Germany -then divided into numerous states of varying political configuration-, the pioneer was Heinrich Schütz, who in 1627 adapted Rinuccini's Dafne,[13] with a clear Monteverdian influence.[64] In 1644, Sigmund Theophil Staden composed Seelewig, the first opera in German.[65] In 1678 the Oper am Gänsemarkt in Hamburg opened, becoming the leading operatic city in the Germanic area.[57] In Munich, the elector Ferdinand Maria of Bavaria sponsored opera, to which Johann Caspar Kerll and Agostino Steffani devoted themselves. The latter inaugurated the Schlossopernhaus in Hannover in 1689 with Enrico Leone.[66]

The leading composer of this period was Reinhard Keiser, the first to write operas entirely in German. He composed several operas that enjoyed great success, such as Adonis (1697), Claudius (1703), Octavia (1705) and Croesus (1710). He was director of the Theater am Gänsemarkt, where he premiered on average about five operas per season; his output is estimated to be between seventy-five and one hundred operas, although only nineteen complete ones survive.[67] Other authors of the period were: Johann Wolfgang Franck (Die drey Töchter Cecrops, 1679)[68] and Christoph Graupner (Dido, Königin von Carthage, 1707; Bellerophon, 1708).[69]

In Austria, Emperor Leopold I of the Holy Roman Empire encouraged opera after hearing Cesti's Il pomo d'oro (1668). Its performance took place at the Hofburg Imperial Palace in Vienna, to which only the court had access.[70] Most were Italian operas, although Austrian composers were gradually added, most notably Heinrich Ignaz Biber: Applausi festivi di Giove (1686), Chi la dura la vince (1687), Arminio (1692).[71] In 1748 the Burgtheater, also located in the Hofburg, was opened. The first public theater was the Theater am Kärntnertor, opened in 1761, which eventually became the official court theater.[70]

In England there was a precedent for opera, the masque (masque), which combined music, dance and theater in verse.[72] During the Puritan Revolution of Oliver Cromwell music was banned. Despite this, the first English opera, The Siege of Rhodes (The Siege of Rhodes), was given in 1656, with libretto by playwright William Davenant and music by five composers: Henry Lawes, Matthew Locke, Henry Cooke, Charles Coleman and George Hudson. Subsequently, the reign of Charles II saw a revival of theatrical and operatic performances.[73] The first opera composer of note was John Blow, organist and composer of the Chapel Royal. He composed preferably religious and entertainment music for the court and was the author of an opera, Venus and Adonis (1682), a short work that included French-influenced ballets.[16] Of particular note was his pupil, Henry Purcell, author of Dido and Aeneas (1689), a French-influenced work with short arias and dances.[74] It was a commission for a college of young ladies, which they were to perform themselves, with a small instrumental ensemble. It is a short work, lasting an hour, but which Purcell resolved brilliantly: its final aria, the so-called "Dido's lament" (When I am laid in earth), enjoys just fame.[75] He also composed several semi-operas inspired by masquerades, including divertissements, songs, choirs and dances, such as Dioclesian (1690), King Arthur (1691), The Fairy Queen (1692), Timon of Athens (1694), The Indian Queen (1695), and The Tempest (1695).[37] This period saw the life of the playwright William Shakespeare, whose plays were adapted to opera on numerous occasions from his time to the present day.[76]

In Poland, opera was sponsored by King Ladislaus IV, who had witnessed an opera performance in Tuscany. In 1632 he created a company with Italian singers, who performed several operas in Warsaw. This company premiered the first opera by a Polish author-although written in Italian-, La fama reale (1633), by Piotr Elert.[77]

.jpg.webp)

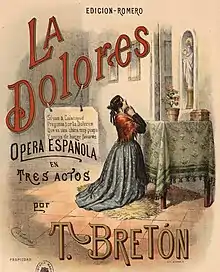

In Spain, opera arrived with some delay due to the social crisis caused by the Thirty Years' War. The first opera was premiered in 1627 at the Alcázar de Madrid: La selva sin amor, a pastoral eclogue composed by Bernardo Monanni and Filippo Piccinini on a text by Lope de Vega; the score is not preserved.[13] Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco composed in 1659 La púrpura de la rosa, with text by Pedro Calderón de la Barca, the first opera composed and performed in America, premiered at the Viceroyal Palace of Lima. Juan Hidalgo was the author of Celos aun del aire matan (1660), also with text by Calderón.[67]

In the late 17th century, King Felipe IV sponsored the performance of operettas at the Zarzuela Palace in Madrid, giving rise to a new genre: the zarzuela.[59] The first zarzuelista was Juan Hidalgo, author in 1658 of El laurel de Apolo, with text by Calderón, which was followed by Ni amor se libra de amor (1662, Calderón de la Barca), La estatua de Prometeo (1670, Calderón de la Barca), Alfeo y Aretusa (1672, Juan Bautista Diamante), Los juegos olímpicos (1673, Agustín de Salazar y Torres), Apolo y Leucotea (1684, Pedro Scotti de Agoiz) and Endimión y Diana (1684, Melchor Fernández de León). Subsequently, the work of Sebastián Durón stood out, with librettos by José de Cañizares (Salir el amor del mundo, 1696), and by Antonio Literes (Júpiter y Dánae, 1708).[78] After the death of Philip IV, the zarzuela moved to the Teatro del Buen Retiro in Madrid.[79]

Neapolitan opera

In the second half of the 17th century, the Neapolitan School introduced a more purist, classicist style, with simplified plots and more cultured and sophisticated operas. At that time, Naples was a Spanish possession, and the opera had the patronage of the Spanish viceroys, especially conde de Oñate. Among the main novelties, a distinction was made between two types of recitative: secco, a declamatory song with basso continuo accompaniment; and accompagnato, a melodic song with orchestral music.[57] In the arias, space was left for vocal improvisations by the singers. Comic characters were eliminated, which gave as a counterpart the inclusion of comic intermezzi which, already in the 18th century, gave rise to the opera buffa.[80] In 1737, the Teatro San Carlo of Naples, one of the most prestigious in the world, was inaugurated.[81]

One of its first composers was Francesco Provenzale, author of Lo schiavo di sua moglie (1672) and Difendere l'offensore overo La Stellidaura vendicante (1674).[82] Also considered a precursor of this type of opera is Alessandro Stradella, despite the fact that he composed most of his operas in Genoa: Trespolo tutore (1677), La forza dell'amor patterno (1678), La gare dell'amor eroico (1679).[83]

Its main representative was Alessandro Scarlatti, who was chapel master of Christina of Sweden and of the viceroy of Naples, as well as director of the Teatro San Bartolomeo in Naples.[83] In his works he introduced numerous novelties: he created the three-part aria (aria da capo), with a theme-variation-theme structure (ABA);[84] he reduced vocal ornamentations and suppressed the improvisations often performed by the singers; he also reduced the recitatives and lengthened the arias, in a recitative-aria alternation, and added a shorter type of arias (cavatina) to give greater speed to the work, performed by secondary characters;[85] on the other hand, together with his usual librettist, Apostolo Zeno, he eliminated the comic characters and the interspersed plots, following only the original story. Scarlattian melody was generally simpler than Monteverdi's, but endowed with a special charm, which led Luigi Fait to comment that "with Scarlatti, Italian opera reaches the height of its beauty".[84] There are 114 known operas by Scarlatti, including Il Mitridate Eupatore (1707), Tigrane (1715), Il trionfo dell'onore (1718) and Griselda (1721).[86] His son Domenico Scarlatti also composed operas: L'Ottavia restituita al soglio (1703), La Dirindina (1715).[87]

.jpg.webp)

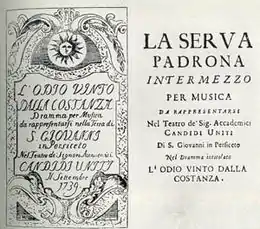

Another outstanding exponent was Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. He died at the age of twenty-six, but had a successful career. In 1732 he composed his first opera, La Salustia, which failed, and Lo frate 'nnamorato, of comic genre, which reaped a notable success. The following year he premiered Il prigionier superbo, in whose intermissions was performed the comic play La serva padrona, which was more successful than the main work. In 1734 he composed Adriano in Siria, with libretto by Pietro Metastasio, in whose intermissions was performed the comic play Livietta e Tracollo, which was more successful than the main work. The following year he premiered L'Olimpiade, still with libretto by Metastasio, and his last work, Il Flaminio, of comic genre, which reaped a notable success.[88]

Nicola Porpora taught singing – he had Farinelli and Caffarelli as pupils – and composition – among his pupils is Johann Adolph Hasse. He was one of the first to musicalize librettos by Pietro Metastasio. Among his early operas are Agrippina (1708), Arianna e Teseo (1714) and Angelica (1720). In 1726 he moved to Venice and, in 1733, to London, where he was musical director of the Opera of the Nobility located at the King's Theatre, where he premiered Arianna in Nasso (1733). He later worked in Dresden, where he premiered Filandro (1747), as well as Vienna, before returning to Naples, where he died in poverty.[88]

Other distinguished representatives were Leonardo Vinci, Leonardo Leo and Giovanni Bononcini. Vinci made his debut at the age of twenty-three with Lo cecato fauzo (The false blind man, 1719). In 1722 he composed Li zite 'ngalera (The lovers of the galley), of comic genre. That same year he reaped a great success with Publio Cornelio Scipione, which turned him towards serious opera. In 1724, he renewed his success with Farnace, which took him to Rome and Venice. It was followed by Didone abbandonata and Siroe, re di Persia, both from 1726 and with libretto by Pietro Metastasio. Until his death in 1730 he composed two operas per year, including Alessandro nell'Indie and Artaserse, both from 1730 and again with librettos by Metastasio.[89] Leo was an organist and church musician. His first opera was Il Pisistrate (1714), at the age of nineteen. In 1725 he was appointed organist of the chapel of the viceroy of Naples. His works were more conservative than those of Vinci and Porpora, based largely on counterpoint. Among them stands out L'Olimpiade (1737), with libretto by Metastasio. He also composed several comic operas, to which he gave respectability for the commitment he put into them.[90] Bononcini had a great initial success with Il trionfo di Camilla (1696, with libretto by Silvio Stampiglia), which was performed in nineteen Italian cities. In 1697 he settled in Vienna, in the service of the emperor Joseph I, until in 1719 he was hired by the Royal Academy of Music in London. His works include Gli affetti più grandi vinti dal più giusto (1701), Griselda (1722) and Zenobia (1737).[91] Mention should also be made of: Francesco Feo (L'amor tirannico, 1713; Siface, 1723; Ipermestra, 1724),[92] Gaetano Latilla (Angelica e Orlando, 1735)[93] and Francesco Mancini Mancini (L'Alfonso, 1699; Idaspe fedele, 1710; Traiano, 1721).[94]

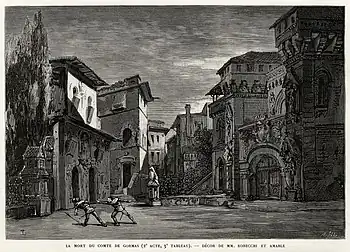

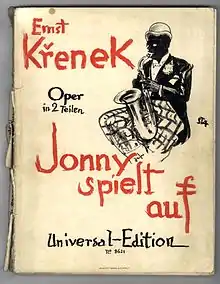

Late Baroque: opera seria and buffa

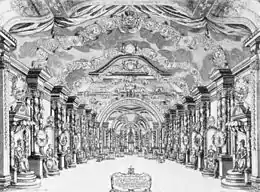

The musical production of the first half of the 18th century is usually called late Baroque. The main center of production continued to be Italy, especially Naples and Venice. In 1732 the Teatro Argentina in Rome was inaugurated.[95] Italian influence spread throughout Europe: Italian companies were established at the Dresden Opera House, at the court of the Elector of Saxony and at the Royal Academy of Music in London. The only non-Italian national school was in France.[96] During this period, scenography developed notably, thanks above all to the Italian Ferdinando Galli Bibbiena —whose work was continued by his sons Antonio and Giuseppe— who introduced theatrical perspective and numerous stage effects.[71] Between 1700 and 1750 was the era of classical bel canto, when the stages were dominated by castrati and prime donne.[97]

Around the second quarter of the 18th century opera was gradually divided into two contrasting genres: the opera seria and the opera buffa.[98] The themes of opera seria were generally drawn from classical mythology, with a moralistic component, showing the more virtuous side of the heroes of old age.[99] Generally, the action was centered on the recitatives and the arias were left for lyrical incursions by the singers, with a preference for the da capo aria, which experienced its golden age.[100] Serious opera wanted to strip lyrical dramas of the extravagances and convoluted plots used until then, with a more sober style inspired by ancient Greek theater. One of its major theorists was Giovanni Vincenzo Gravina, co-founder of the Academy of Arcadia.[101]

However, the disappearance of comic characters left a certain void in a sector of the public, generally lower class, who liked these characters. To satisfy them, intermezzi were introduced in the intermissions of the plays, which gradually gained success until they became separate works.[102] A good example was La serva padrona by Pergolesi (1733). From then on these intermezzi became independent and became shows of their own. The opera buffa was of comic genre, intended for a more popular audience, influenced by the Commedia dell'arte. It included arias and recitatives, but with second-rank performers, who sang with their natural voices, without castrati or sopranos. The arias were shorter and the recitatives kept the music, unlike in Spanish zarzuela or German singspiel, which included only spoken parts. There were also duets, trios and quartets, absent from opera seria.[103] In opera buffa a type of rapid, syllabic declamation called parlando was characteristic. Also frequent was the presence of stuttering, yawning or sneezing.[104] The music, generally stringed, was simple, of small orchestras, although over time it would be equated with that of opera seria. Eventually, both genres tended to merge, with the appearance of the semi-serious opera or dramma giocoso.[105]

Some of the characteristic elements of the opera buffa were: the use of the recitative accompagnato, greater use of choir and ensembles, and the use of the cavatina and the aria con pertichini, a modality based on an aria -generally da capo – to which were added comments in recitative by characters who watched the scene from outside, generating a form of ensemble. The introduzione and the finale, scenes that usually brought together all the characters of the work, singing in ensemble, also became more relevant.[106]

In the field of opera seria, a unique phenomenon in the history of opera took place in this period: librettists were more relevant than composers, especially two: Apostolo Zeno and Pietro Metastasio.[101] Zeno was a Venetian historian and librarian who, after dabbling in the field of opera libretti, was always eager to have them considered a literary genre of the first rank. In 1718, he replaced Silvio Stampiglia as imperial poet of Charles VI, for whom he was also imperial historiographer. He introduced historical themes into opera and, in his plots, always incorporated a code of honor to serve as an example for the public. He wrote thirty-five librettos, some of them in collaboration with Pietro Pariati, which were set to music by composers such as Albinoni, Caldara, Gasparini, Scarlatti and Händel.[107] A generation younger, Metastasio was directly influenced by Zeno, whom he replaced as imperial poet. In a fifty-year career he wrote twenty-seven librettos that were set to music in some one hundred operas. He was a great reformer of operatic writing, to the point that one often speaks of "metastasian opera" for his works. His librettos were elegant and sophisticated, and he gave greater prominence to the soloists.[108] Zeno and Metastasio introduced the so-called "doctrine of the affections", whereby every emotion (love, hate, sadness, hope, despair) was expressed by a certain musical form (aria, chorale, instrumental movement).[109]

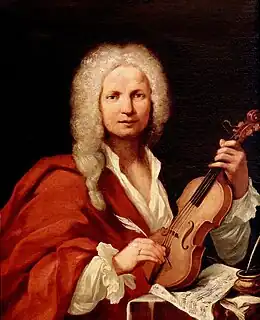

Venice remained one of the main operatic centers. Antonio Vivaldi, the main representative of the Italian late-baroque school, stood out. He was chapel master of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, where he was able to rely on the orphans of the hospice to form a large orchestra, for which he is considered the first great master of orchestral music.[110] He devoted himself to opera both as a composer and impresario. In 1739 he claimed to have written ninety-four operas, although only about fifty librettos and twenty scores survive. Notable among his works are: Ottone in villa (1713), Orlando finto pazzo (1714), La costanza trionfante degl'amori e degl'odii (1716), Teuzzone (1719), Tito Manlio (1719), Il Giustino (1724), Farnace' (1727), Orlando furioso(1727), Bajazet (1735), Ginevra (1736) and Catone in Utica (1737).[89]

Tomaso Albinoni was a brilliant composer, famous for his Adagio, although he also dabbled in opera. Concerned with the harmony of the vocal ensemble, he provided serenity and balance to the slow movements, with special attention to the lower voices.[111] His works include Zenobia, regina dei Palmireni (1694), Pimpinone (1708) and Didone abbandonata (1724).[112] Other Venetian composers of the period were: Ferdinando Bertoni (Orfeo ed Euridice, 1776; Quinto Fabio, 1778)[113] and Francesco Gasparini (Roderico, 1694; Ambleto, 1705; Il Bajazet, 1719).[114]

The Neapolitan school also continued, where the split between opera seria and opera buffa took place. Its main representatives in this period were Niccolò Jommelli and Tommaso Traetta. Jommelli premiered his first operas in Naples: L'errore amoroso (1737), Ricimero (1740) and Astianatte (1741). After reaping fame for these works he was appointed chapel master of St. Peter's at the Vatican in 1749 and, four years later, the same position in Stuttgart, for the duke of Württemberg. In Germany he composed thirty-three operas, and his style became so Germanized that on his return to his homeland his works were rejected by the public.[115] Traetta was influenced by gluckian influence, which he combined with his prodigious ability to compose chorales and elegant melodies. His first compositions were for opera houses in Naples and Parma (Ippolito e Aricia, 1759; Iphigenia in Tauride, 1763). In 1765 he moved to Venice and, in 1768, to Russia, where he was appointed opera director by Empress Catherine II. There he composed, among others, Antigone (1772).[116]

The Spanish Domingo Terradellas (also known in Italian as Domenico Terradeglias) is considered to belong to the Neapolitan school. He studied in Naples, where he was a pupil of Francesco Durante. In 1736 he premiered his first opera, Giuseppe riconosciuto. He moved to Rome, where he was chapel master of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli and premiered Astarto (1739), Merope (1743) and Semiramide riconosciuta (1746). He then went to London, where he composed Mitridate (1746) and Bellerofonte (1747). Back in Italy, he premiered in Turin Didone (1750), in Venice Imeneo in Atene (1750) and in Rome Sesostri (1751).[117]

Mention should also be made of Gian Francesco de Majo and Davide Perez. The former began with Ricimero, re dei Goti (1759) and L'Almeria (1761). He spent some time in Mannheim, where he premiered Iphigenia in Tauride (1764), which influenced Gluck. Back in Naples, he made L'Ulisse (1769) and L'eroe cinese (1770).[118] Perez, of Spanish origin, composed some buffa operas (La nemica amante, 1735), but mainly serious ones: Siroe (1740), Astarto (1743), Merope (1744), La clemenza di Tito (1749), Demofoonte (1752), Olimpiade (1754), Solimano (1757).[119] Other representatives of the Neapolitan school were: Girolamo Abos (Artaserse, 1746; Alessandro nell'Indie, 1747),[120] Pasquale Cafaro (La disfatta di Dario, 1756; Creso, 1768),[121] Ignazio Fiorillo (L'Olimpiade, 1745),[122] Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi (L'Olimpiade, 1763; Farnace, 1765; Sesostri, 1766; Alceste, 1768),[123] Giacomo Insanguine (L'osteria di Marechiaro, 1768; Didone abbandonata, 1770)[124] and Antonio Sacchini (La contadina in corte, 1765).[125]

From the rest of Italy it is worth mentioning Antonio Caldara. He was maestro de cappella in Mantua and Rome before being appointed vice maestro de cappella of Emperor Charles VI in Vienna, where he remained for about twenty years. He collaborated regularly with the librettists Zeno and Metastasio. His work is notable for its use of large chorales. Among his works stand out: Il più bel nome (1708), Andromaca (1724), Demetrio (1731), Adriano in Siria (1732), L'Olimpiade (1733), Demofoonte (1733), Achille in Sciro (1736) and Ciro riconosciuto (1736).[90] Mention should also be made of the Milanese Giovanni Battista Lampugnani (Candace, 1732; Antigono, 1736).[126]

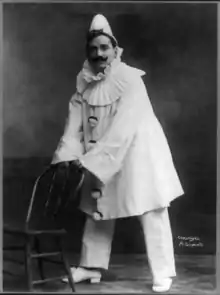

%252C_1794.jpg.webp)

A librettist also stood out in opera buffa: Carlo Goldoni. A lawyer by profession, he worked as a librettist for several Venetian theaters. He wrote about a hundred librettos, in which he incorporated elements of the Commedia dell'arte, the typical Italian popular theater of Renaissance origin. His works featured real characters and everyday events, with simpler plots and witty dialogues that helped to humanize opera. His work influenced composers such as Mozart and, later, Rossini and Donizetti.[108]

Among the composers of opera buffa were Niccolò Piccinni and Baldassare Galuppi. The former was a prolific composer, author of about one hundred and twenty works. He began his career with Le donne dispettose (1754). His greatest success was La Cecchina, ossia la buona figliuola (1760), with libretto by Goldoni based on Pamela by Samuel Richardson, which is usually considered the first semi-serious opera. In 1776 he was invited to Paris, where he had a tense rivalry with Gluck: both composed an Gluck's opera (1779) was more successful than Piccinni's (1781).[127] Piccinni introduced the rondo aria, which had a slow and fast two-part structure, repeated twice.[128] Galuppi wrote his first opera at the age of sixteen (La fede nell'incostanza, 1722). His first great success was with Dorinda in 1729. He composed about a hundred operas, a good part of them written for London: Scipione in Cartagine (1742), Sirbace (1743). In 1749 he composed L'Arcadia in Brenta, with a libretto by Carlo Goldoni, the first opera buffa of great length. It was followed by other comic operas such as Il mondo della luna (1750), Il mondo alla roversa (1750), La diavolessa (1755) and La cantarina (1756), but Galuppi and Goldoni's most famous joint work was the dramma giocoso Il filosofo di campagna (1754).[129]

Other authors of opera buffa were: Pasquale Anfossi (La finta giardiniera, 1774; La maga Circe, 1788),[130] Gennaro Astarita (Il corsaro algerino, 1765; L'astuta cameriera, 1770),[131] Francesco Coradini (Lo 'ngiegno de le femmine, 1724; L'oracolo di Dejana, 1725),[132] Domenico Fischietti (Il mercato di Malmantile, 1756),[133] Giuseppe Gazzaniga (Don Giovanni Tenorio, 1787),[134] Nicola Logroscino (Il governatore, 1747)[135] and Giacomo Tritto (La fedeltà in amore, 1764).[131]

At this time also appeared the pasticcio, an opera composed jointly by several composers. The first was Muzio Scevola (1721), which consisted of three acts each composed by Filippo Amadei, Giovanni Bononcini and Georg Friedrich Händel. Generally, rather than collaborating in a single homogeneous whole, most pasticci were a conglomerate of music, songs, dances, arias and chorales, which could be added successively.[101]

In the vocal field, at this time it is worth remembering the sopranos Francesca Cuzzoni, Margherita Durastanti and Anna Maria Strada, and the mezzo-soprano Faustina Bordoni, who all performed in London for Händel. Bordoni and Cuzzoni maintained a strong rivalry between them, to the point that they came to blows in the performance of Bononcini's Astianatte in 1727. On the other hand, this was the golden age of the castrati, among whom Giovanni Carestini, Carlo Broschi "Farinelli", Nicolò Grimaldi "Nicolini", Francesco Bernardi "Senesino" and Antonio Maria Bernacchi stood out. The most famous was Farinelli, who performed all over Europe with great success. He retired at the age of thirty-two, at the height of his fame, and entered the service of Philip V of Spain.[136]

France

At the beginning of this period the Lullian tragédie-lyrique still predominated, where the taste for ballet stood out. Just as Italian opera tended to have three long acts, French opera had five short ones, with ballets interspersed.[99] The most prominent operatist of this period was Jean-Philippe Rameau. He held several jobs as organist and chapel master in various French cathedrals, while writing various treatises on music theory. It was not until he was fifty that he composed his first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), which was followed by Les Indes galantes (1735), Castor et Pollux (1737) and Dardanus (1739). After a few years of inactivity, in 1745 he composed La Princesse de Navarre, Le temple de la gloire —both by Voltaire— and the comic opera Platée. His last works include Zoroastre (1749) and Les boréades (1763). Rameau's operas enjoyed great popularity, while at the same time sparking intense debates between their defenders and detractors: in 1733 the so-called quarrel of Lullyists and Ramists broke out, between those who advocated maintaining the operatic tradition initiated by Lully and those who viewed with pleasure the new form introduced by Rameau, which placed more emphasis on the music than on the text.[137] Similarly, in the 1750s the so-called jester's quarrel arose between supporters of Rameau, advocates of French opera seria, and the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and his followers, supporters of Italian opera buffa.[138]

André Cardinal Destouches was director of the Paris Opera from 1728 to 1731. His work influenced Rameau. He was the author of operas such as Omphale (1700), Callirhoé (1712), Télémaque (1714), Les Élémens (1721) and Les Stratagèmes de l'amour (1726).[139] Henri Desmarets was a chapel master in the French Jesuit Order until, accused of the murder of his wife, he settled in Spain, where he served Philip V. He later lived in the Duchy of Lorraine, where his opera Le Temple d'Astrée opened the Nancy Theater in 1708.[140] Another exponent was Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (Jephté, 1732).[141]

The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was also an amateur composer, composed an opera, Le devin du village, in 1752. It was of poor quality, but was influential for its introduction of country characters shown as simple and virtuous people, as opposed to the cynical and corrupt nobility, ideals that were echoed in the French Revolution.[108]

In France, opera buffa had its equivalent in the opéra-comique,[13] a type of simple shows, with contemporary plots, generally of domestic and urban cut, and of conservative tone, in which technical innovations, cultural currents and social aspects in general, as well as the defects and customs of the characters, were ridiculed. It had certain elements in common with the Italian opera buffa, such as the taste for costumes and transvestism, or the characters inspired by the Commedia dell'arte. It was frequent the presence of a type of songs known as vaudeville.[142] For this type of performances the Théâtre National de l'Opéra-Comique was created. Its main representatives were François-André Danican Philidor and André Ernest Modeste Grétry. The first one started in Italian opera, but when the public did not like it, he switched to comic opera, where he reaped great successes: Blaise le savetier (1759), Le sorcier (1764), Tom Jones (1765), Ernelinde, princesse de Norvège (1767). In his works he introduced extramusical sounds, such as that of a hammer or the braying of a donkey.[143] Grétry won over audiences with his elegant and expressive melodies. His first success was Le Huron (1768), which was followed by Lucile and Le tableau parlant in 1769. He tried the serious genre with Andromaque (1780), which he did not resolve as well as his comic works. His greatest success was Richard Cœur-de-lion (1784).[144]

Other opéra-comique composers were: Nicolas Dalayrac (Nina, ou La Folle par amour, 1786),[145] Antoine Dauvergne (Les troqueurs, 1753),[146] Egidio Romualdo Duni (Ninette à la cour, 1755; La fée Urgèle, 1765),[147] François-Joseph Gossec (Les Pêcheurs de perles, 1766; Toinin et Toinette, 1767)[148] and Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny (Le Cadi dupé, 1761; Le Roi et le fermier, 1762; Rose et Colas, 1764; Le Déserteur, 1769).[149]

Germany and Austria

An indigenous style did not flourish in Germany, and the structure of Italian opera was generally followed.[150] However, the singspiel emerged as a minor genre of comic tone, analogous to the French opéra-comique and the Spanish zarzuela, which alternated dialogue with music and song. The earliest example was Croesus by Reinhard Keiser (1711).[100]

Georg Philipp Telemann performed operas with arias in Italian and recitatives in German. A precocious musician, he composed his first opera at the age of twelve. He was a composer, organist, conductor and creator of the first musical magazine in history, Der getreue Musikmeister. However, his work fell into oblivion and was not recovered until the early 20th century, although his operas today are not performed on the operatic theater circuit.[151] It is estimated that he composed about fifty operas, although only nine are preserved, including Germanicus (1704), Pimpinone (1725) and Don Quichotte auf der Hochzeit des Camacho (Don Quixote at Camacho's Wedding, 1761).[152]

One of the best operatists of the time was Georg Friedrich Händel. A disciple of Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, in 1703 he settled in Hamburg, where he composed his first opera, Almira, in 1705, at the age of nineteen.[153] In 1707 he traveled to Rome, Venice and Florence, the latter city where he premiered his first opera, Rodrigo.[154] Despite his origins, he wrote all his operas in Italian. In 1708 he traveled to Naples, where he made contact with the notable operatic school of that city. In 1710 he premiered Agrippina in Venice, which was a great success.[155] In his works he brought together Italian and French influences, without lacking his Germanic character.[156] Shortly thereafter, he returned to his homeland, where he became the chapel master to Prince Elector George of Hanover, who in 1714 became George I of Great Britain. In 1712 he settled in England, where he developed most of his work, and where he was conductor of the orchestra of the Royal Academy of Music, which was based at the King's Theatre.[157] He composed forty-two operas, usually solemn and grandiose works, where he usually incorporated choirs, though not ballets like the French. He had a preference for heroic plots and his protagonists were usually heroes of antiquity, whether historical or mythological, such as Theseus, Jerxes, Alexander the Great, Scipio or Julius Caesar.[158] His works include: Rinaldo (1711), Amadigi di Gaula (1715), Giulio Cesare in Egitto (1724), Tamerlano (1724), Rodelinda (1725), Admeto (1727), Tolomeo (1728), Orlando (1732), Ariodante (1735), Alcina (1735), Serse (1738) and Imeneo (1740).[153] His regular librettist was Nicola Francesco Haym.[159]

Other exponents were Johann Adolph Hasse, Johann Joseph Fux and Johann Mattheson. Hasse studied in Naples with Scarlatti. His first opera was Antioco (1721), at the age of twenty-two, followed by Sesostrate (1726) and La sorella amante (1729). In 1730 he premiered in Venice Artaserse, which was innovative for its expressive contrasts that allowed a great showcasing of the singers. That year he was appointed director of the Dresden Opera, where he was one of the main promoters of opera seria.[143] He left some seventy operas.[160] Fux was the author of eighteen operas, mostly with librettos by Pietro Pariati, though also by Zeno and Metastasio. His greatest success was Costanza e Fortezza (1723), premiered in Prague at the coronation of Emperor Charles VI as king of Bohemia.[90] Mattheson was a tenor as well as a composer. He worked as an assistant to other operatists, including Keiser, before composing his own. In 1715 he was appointed director of music at Hamburg Cathedral. His works include Cleopatra (1704).[90]

Other countries

In England, too, no national school emerged and the public remained faithful to Italian opera. In 1707, an attempt at English opera, Rosamund, by the musician Thomas Clayton and the writer Joseph Addison, was a resounding failure. In the same year, the opera Semele by John Eccles —with a libretto by William Congreve— was not even premiered. Just as in Germany works with recitative in German and arias in Italian were produced, in England the introduction of the English language did not take off either. Thus, the operatic scene was largely dominated by Handel, along with the premiere of Italian productions.[150] In 1732 the Theatre Royal —also known as Covent Garden— in London, the country's main operatic center, rebuilt in 1809 and 1858; since 1892 it has been called the Royal Opera House.[161]

However, as time went on, audiences began to tire of Händelian operas, which explains the success of The Beggar's Opera (The Beggar's Opera, 1728), a sort of Italian anti-opera with music by Johann Christoph Pepusch and libretto by John Gay, a reaction to Händel's somewhat pompous solemnity.[162] This work inaugurated the ballad opera genre, equivalent to the operetta, the Spanish zarzuela or the German singspiel. They were works based on ballads and short songs, with folk dances and melodies.[163] There also emerged the afterpieces, short works performed during the intermissions of theatrical works, in the style of the Italian intermezzi.[116] Some exponents were Samuel Arnold (The Maid of the Mill, 1765),[164] Charles Dibdin (The Waterman, 1774),[129] Stephen Storace (The Haunted Tower, 1789; The Pirates, 1792)[116] and William Shield (The Magic Cavern, 1784; The Enchanted Castle, 1786; The Crusade, 1790).[116]

A last attempt at English opera was led by Thomas Arne, composer and producer. He was the author of the comic opera Rosamond (1733) and the serious Comus (1738), as well as the masquerade Alfred (1740), whose song Rule, Britannia! became an English patriotic anthem. He subsequently composed Artaxerxes (1762) —in English— and L'Olimpiade (1765) —in Italian— both with libretto by Pietro Metastasio.[91]

In Denmark, King Federick V protected opera and welcomed the Italian composer Giuseppe Sarti, author of the first opera in Danish: Gam og Signe (1756).[165] Prominent among Danish composers was Friedrich Ludwig Æmilius Kunzen, author of Holger Danske (Holger the Dane, 1789), while the German Johann Abraham Peter Schulz introduced the singspiel genre in Danish (Høstgildet [Harvest Festival], 1790).[166]

In Spain, during the reign of Felipe V, numerous Italian singers and composers settled in the country, among them the famous Farinelli. Among the works produced in these years are Júpiter y Anfitrión (1720), by Giacomo Facco and libretto by José de Cañizares; and El rapto de las sabinas (1735), by Francesco Corselli.[13] Fernando VI and Bárbara de Braganza were lovers of Italian opera, and favored the stay of composers such as Francesco Coradini and Giovanni Battista Mele.[167]

With the coming to power of the Bourbons zarzuela declined, due to the preference of the new rulers for Italian opera. However, during the reign of Carlos III it briefly resurfaced, due to the rejection of Italian opera caused by popular discontent with the monarch's Italian ministers. Of particular note was the sainetista Ramón de la Cruz, who defined in his works the so-called casticismo madrileño: among his works it is worth mentioning Las segadoras de Vallecas (1768), with music by Antonio Rodríguez de Hita.[78] Another exponent was José de Nebra, author of Viento es la dicha de amor (1743) and Where there is violence, there is no guilt (1744), among others.[168]

In Barcelona, the marqués de la Mina encouraged opera and sponsored the installation of an Italian company in the Teatro de la Santa Cruz, in which worked the composer Giuseppe Scolari, who premiered some operas such as Alessandro nell'Indie (1750) and Didone abbandonata (1752). There was also a local composer, Josep Duran, author of Antigono (1760) and Temistocle (1762).[169]

During this period there was also the genre of the tonadilla, some works of lyrical-theatrical character and of satirical and picaresque sign, which were represented in the theatrical intermissions along with sainetes or entremeses. It occurred mainly in the second half of the 18th century. The first work of this genre was Una mesonera y un arriero (1757), by Luis de Misón. Other authors were Antonio Guerrero, Blas de Laserna, Pablo Esteve and Fernando Ferandiere.[170]

In Portugal, opera was supported by King John V, who favored the installation of Italian composers, such as Domenico Scarlatti.[171] Among the Portuguese composers, it is worth mentioning Francisco António de Almeida, author of Italian operas: La pazienzia di Socrate (1733) and La Spinalba, ovvero Il vecchio matto (1739).[172]

Galant music and gluckian reform

In the second third of the 18th century some voices began to emerge critical of opera seria, which was considered stultified and too much geared to vocal flourishes. The first criticisms came from some writings such as Il teatro alla moda by Benedetto Marcello (1720)[173] or Saggio sull'opera by Francesco Algarotti (1755).[174] It was the time of the rococo, which in music gave the so-called galant music, calmer than the baroque, lighter and simpler, gentle, decorative, melodic and sentimental. The taste for contrast disappeared and the sonorous gradation was sought (crescendo, diminuendo).[175] In the so-called Mannheim School, symphonic music developed, with the first large modern orchestra (40 instruments), an initiative of the elector Charles Theodore of Wittelsbach. Its main representative, Johann Stamitz, is considered the first conductor.[176]

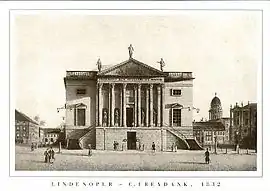

The main center of galant music was the Germanic area (Germany and Austria), where it is known as Empfindsamer Stil ("sentimental style"). In Germany, it had an early precedent in the late work of Telemann and Mattheson. Its main representative was Johann Christian Bach, probably the most gifted of Johann Sebastian Bach's sons. He lived for a time in Italy, where he converted to Catholicism and married an opera singer, a fact that would undoubtedly influence him to approach a genre that neither his father nor his brothers had treated. With a great mastery of instrumental music, he combined the simplicity and clarity of Italian music with Germanic precision. He later settled in England, where he was director of the Theatre Royal in London. His work influenced Mozart, whom he even gave lessons to when the latter traveled to London at the age of eight.[177] His works include: Artaserse (1760), Catone in Utica (1761), Alessandro nell'Indie (1762), Orione (1762), Lucio Silla (1775), La clemenza di Scipione (1778) and Amadis de Gaule (1779).[178] Another exponent was Carl Heinrich Graun, chapel master to Frederick II of Prussia. His opera Cleopatra e Cesare opened the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin in 1742. King Frederick himself wrote the libretto for his opera Montezuma (1755). Generally, his operas followed the Italian style, influenced by Scarlatti.[175] It is worth mentioning that Frederick II's sister, Wilhelmina of Prussia, was a composer of an opera (Argenore, 1740) and promoted the creation of the Markgräfliches Theater in Bayreuth.[179]

In Austria, Florian Leopold Gassmann, of Czech origin, composed several operas – preferably buffas – for Empress Maria Theresa: L'amore artigiano (1767), La notte critica (1768), La contessina (1770), Il filosofo innamorato (1771), Le pescatrici (1771).[114] Ignaz Holzbauer was one of the first Germanic composers to compose operas with recitative instead of dialogue, such as Günther von Schwarzburg (1776), a work admired by Mozart.[180] The Czech Josef Mysliveček studied in Italy, where he premiered most of his works: Il Bellerofonte (1767), Demofoonte (1775), L'Olimpiade (1778).[181]

In the Germanic sphere was the golden age of singspiel: in 1778, Joseph II renamed the French Theater in Vienna as Deutsches Nationaltheater (now Burgtheater) and dedicated it to this genre, which premiered with Die Bergknappen (The Miners), by Ignaz Umlauf.[182] The most prominent composers of singspiel were Johann Adam Hiller (Der Teufel ist los [The Devil is on the loose], 1766; Der Jagd [The Hunt], 1770)[183] and Georg Anton Benda (Der Dorfjahrmarkt [The Village Fair], 1775; Romeo und Julie, 1776).[184] Other exponents were: Karl von Ordonez (Diesmal hat der Mann den Willen [This time the decision is man's], 1778),[185] Johann André (Erwin und Elmire, 1775),[186] Christian Gottlob Neefe (Adelheit von Veltheim, 1780), Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (Doktor und Apotheker [Physician and Pharmacist], 1786),[187] Anton Eberl (Die Marchande des Modes, 1787),[186] Paul Wranitzky (Oberon, König der Elfen [Oberon, King of the Elves], 1789),[188] Johann Friedrich Reichardt (Erwin und Elmire, 1790),[189] Johann Baptist Schenk (Der Dorfbarbier [The Village Barber], 1796)[186] and Wenzel Müller (Die Teufelmühle [The Devil's Mill], 1799).[190]

In France, the galant style was already denoted in the work of Rameau and, more fully, in Joseph Bodin de Boismortier (Les Voyages de l'Amour, 1736; Daphnis et Chloé, 1747) and Jean-Joseph de Mondonville (Daphnis et Alcimadure, 1754).[191]

In Italy, gallant music had less incidence, given the presence of the Venetian and Neapolitan schools. Even so, it is denoted in the work of Niccolò Piccinni, Domenico Scarlatti and Baldassare Galuppi, as well as in Pietro Domenico Paradisi (Alessandro in Persia, 1738; Le muse in gara, 1740; Fetonte 1747; La Forza d'amore, 1751), Giovanni Marco Rutini (I matrimoni in maschera, 1763; L'olandese in Italia, 1765),[192] Felice Alessandri (Ezio, 1767; Adriano in Syria, 1779; Demofoonte, 1783) and Giovanni Battista Martini (Don Chisciotte, 1746).[193]

During this period a reform in opera was introduced that pointed to a change of style that would culminate in classicism. Its architect was the German Christoph Willibald Gluck. He studied in Milan, where he premiered in 1741 Artaserse, with a libretto by Metastasio. In 1745 he moved to London, where he unsuccessfully sought Händel's support; he therefore settled in Vienna the following year, until 1770, when he settled in Paris.[194] Among the reforms introduced by Gluck were: preeminence of the plot over vocal improvisations, with more truthful characters; austere music, without ornamentation; limitation of recitatives, all with orchestral accompaniment; overture, choir and ballet are integrated into the action of the opera; abolition of the da capo in the arias; music at the service of the text, harmonizing both elements.[195] On the other hand, as opposed to the concept of closed numbers of Italian opera, Gluck introduced the tableau ("tableau"), a scenic concept that turned each act into a dramatic-musical unit encompassing soloists, choir, ensembles and ballets, which formed an organic ensemble scene. This concept was especially developed in 19th-century French opera.[196]

Among his works are: Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), Alceste (1767) and Paride ed Elena (1770), premiered in Vienna; and Iphigénie en Aulide (1774), Armide (1777), Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) and Écho et Narcisse (1779), premiered in Paris. His regular librettist was Raniero di Calzabigi.[197] During his stay in France, the so-called quarrel of Gluckists and Piccinnists (1775–1779) arose between supporters of Gluck's reform and supporters of Italian opera.[198] Gluck did not limit himself to his Reform-Opern (renewed opera), but made some comic works in the Italian style, such as L'ivrogne corrigé (The Corrected Beodle, 1760) and La rencontre imprévue (The Unforeseen Encounter, 1764).[186]

Classicism

The classical music—not to be confused with the general concept of "classical music" understood as the vocal and instrumental music of cultured tradition produced from the Middle Ages to the present day—[note 5] it meant between the last third of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century the culmination of instrumental forms, consolidated with the definitive structuring of the modern orchestra.[199] Classicism was manifested in the balance and serenity of composition, the search for formal beauty, for perfection, in harmonious and inspiring forms of high values. It sought the creation of a universal musical language, a harmonization between form and musical content. The taste of the public began to be valued, which gave rise to a new way of producing musical works, as well as new forms of patronage.[200]

Opera continued to enjoy great popularity, although it underwent a gradual evolution in accordance with the novelties introduced by classicism. Along with solo voices there were duos, trios, quartets and other ensembles —even a sextet in Le Nozze di Figaro by Mozart-, as well as choirs, although not as grandiose as the baroque ones. The orchestra was enlarged and instrumental music became increasingly prominent in relation to the vocal line.[201] In 1778 the La Scala Theater of Milan was inaugurated, one of the most famous in the world, with an auditorium of 2800 spectators.[202] Similarly, in 1792 the La Fenice Theater in Venice opened, which has also enjoyed great prestige.[203]

The main composers of classicism were Franz Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven. Haydn, considered the father of the symphony,[199] was a great innovator in the field of music. Self-taught, in his youth he played in street bands, until he entered the service of Prince Pál Antal Esterházy, in whose palace in Eisenstadt he lived for thirty years. He created an orchestra close to the modern one, with a correlation between strings and winds. Haydn gave the symphony the so-called "sonata form", in four movements. Opera was not Haydn's main interest, but he composed several for the Esterházy court, usually comic; today they are not usually in the operatic repertoire.[204] These include: Acide e Galatea (1763), La canterina (1766), Lo speziale (1768), Le pescatrici (1770), L'infedeltà delusa (1773), L'incontro improvviso (1775), Il mondo della luna (1777), La vera costanza (1779), L'isola disabitata (1779), La fedeltà premiata (1781), Orlando paladino (1782), Armida (1784) and L'anima del filosofo (1791).[109]

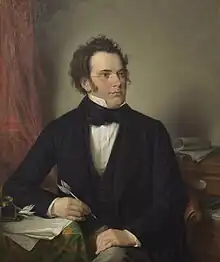

The main exponent of classicism was the Austrian Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. He was a child prodigy, who toured Europe with his father between the ages of six and fourteen, becoming acquainted with the main musical currents of the time: Italian and French opera, Gallant music, Mannheim school.[205] In his native Salzburg, he performed in 1767 the sacred singspiel Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots (The Obligation of the First Commandment), at the age of only eleven.[206] That same year he performed for the university an operetta in Latin, Apollo et Hyacinthus. The following year he composed the singspiel Bastien und Bastienne, a parody of Le devin du village by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[207] That year he received a commission from the grand duke of Tuscany Leopold – future Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II — for an Italian opera buffa, and produced La finta semplice. During a stay in Naples he composed Mitridate, re di Ponto (1770), his first serious opera, which reaped a notable success, and featured a richer and more elegant orchestration than the Italian operas of the time.[208] In the following two years he composed two serenatas, operettas to be performed in a salon: Ascanio in Alba (1771) and Il sogno di Scipione (1772), the latter with libretto by Metastasio. That year he produced Lucio Silla, of Gluckian influence.[209] In 1775 he received a commission from Munich and produced La finta giardiniera, of comic tone, still in the Baroque style. That year he produced Il re pastore, a pastoral serenade.[210] Again in Salzburg, between 1779 and 1780 he began Zaide, a singspiel which he left unfinished. Idomeneo, re di Creta (1781) was a new commission from Munich. This work marked his entry into musical maturity and his gradual abandonment of the baroque.[211]

After the success of Idomeneo he settled in Vienna, where he was commissioned by Emperor Joseph II to write an opera in German, given the pan-Germanist policy of the monarch. In 1782 he premiered at the Burgtheater Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), set in a Turkish harem. This work broke completely with the baroque style, especially by breaking with the succession of arias and the inclusion of real characters, who express their feelings. Depending on the plot he introduced various musical styles, such as folk music to accompany the maid, or passages with Turkish music, characterized by its strident percussion.[212] He employed a denser orchestra, with more wind instruments. He also introduced an aria in two parts, one slower and one faster (cabaletta). At the end he introduced a vaudeville, a scene that brings together all the characters on stage, whose text makes a synthesis of what happened in the play.[213][note 6]

After two unfinished buffa operas in 1783 (L'oca del Cairo and Lo sposo deluso), it was not until three years later that he received other commissions in 1786: Der Schauspieldirektor (The Theater Director) and Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). The latter was an opera buffa with libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte, based on Le mariage de Figaro by Pierre-Augustin de Beaumarchais. In it he showed his mastery of the vocal ensemble, introducing a sextet in act three.[214] He also showed admirable psychological skill in the treatment of the characters, as well as in the various emotional qualities of the instruments (clarinet for love, oboe for grief, bassoon for irony).[215] The following year he produced Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni, also with libretto by Da Ponte, based equally on Tirso de Molina's Don Juan and Molière, commissioned by the Prague State Theater. In this work he combined tragedy and comedy in equal parts.[216] In 1790 he produced Così fan tutte (Thus do they all), his last collaboration with Da Ponte, which was considered frivolous and immoral.[217] His last two operas are from the year of his death (1791): La clemenza di Tito, opera seria with libretto by Metastasio, and Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), a singspiel with libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The latter mixed a fairy tale with a masonic allegory, and was one of his most accomplished works.[218]

Another outstanding composer of classicism was Ludwig van Beethoven, halfway to Romanticism. In 1803 he attempted an opera, Vestas Feuer, with a libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder, but the project remained unfinished. Two years later he made what would be his only opera, Fidelio (1805), a singspiel of political-moral character, a drama of romantic style, based on Léonore, ou l'amour conjugale by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly. In this work he denoted the influence of Mozart, especially Così fan tutte and Die Zauberflöte.[219] Due to the little experience he had in the field of opera, the music of this work was symphonic, with an instrumentation so dense that it demanded great efforts from the singers.[220] He later made other attempts to compose operas, such as a Macbeth (1808–1811) or a fairy tale entitled Melusine (1823–1824), which he left incomplete.[221]

In the Germanic sphere mention should likewise be made of: Franz Seraph von Destouches (Die Thomasnacht [The Night of Thomas], 1792; Das Mißverständnis [The Misunderstanding], 1805),[139] Anton Reicha (Argene, regina di Granata, 1806; Natalie, 1816),[189] Joseph Weigl (La principessa d'Amalfi, 1794; Die Schweizerfamilie [The Swiss Family], 1809)[222] and Peter von Winter (Das unterbochene Opferfest [The Interrupted Offering Party], 1796; Der Sturm [The Tempest], 1798; Maometto, 1817).[223]