History of tattooing

Tattooing has been practiced across the globe since at least Neolithic times, as evidenced by mummified preserved skin, ancient art and the archaeological record.[1][2] Both ancient art and archaeological finds of possible tattoo tools suggest tattooing was practiced by the Upper Paleolithic period in Europe. However, direct evidence for tattooing on mummified human skin extends only to the 4th millennium BC. The oldest discovery of tattooed human skin to date is found on the body of Ötzi the Iceman, dating to between 3370 and 3100 BC.[3] Other tattooed mummies have been recovered from at least 49 archaeological sites, including locations in Greenland, Alaska, Siberia, Mongolia, western China, Egypt, Sudan, the Philippines and the Andes.[4] These include Amunet, Priestess of the Goddess Hathor from ancient Egypt (c. 2134–1991 BC), multiple mummies from Siberia including the Pazyryk culture of Russia and from several cultures throughout Pre-Columbian South America.[3]

Ancient practices

Preserved tattoos on ancient mummified human remains reveal that tattooing has been practiced throughout the world for millennia.[3] In 2015, scientific re-assessment of the age of the two oldest known tattooed mummies identified Ötzi as the oldest example then known. This body, with 61 tattoos, was found embedded in glacial ice in the Alps, and was dated to 3250 BCE.[3][5] In 2018, the oldest figurative tattoos in the world were discovered on two mummies from Egypt which are dated between 3351 and 3017 BCE.[6]

Ancient tattooing was most widely practiced among the Austronesian people. It was one of the early technologies developed by the Pre-Austronesians in Taiwan and coastal South China prior to at least 1500 BCE, before the Austronesian expansion into the islands of the Indo-Pacific.[7][8][9] It may have originally been associated with headhunting.[10] Tattooing traditions, including facial tattooing, can be found among all Austronesian subgroups, including Taiwanese Aborigines, Islander Southeast Asians, Micronesians, Polynesians, and the Malagasy people. For the most part Austronesians used characteristic perpendicularly hafted tattooing points that were tapped on the handle with a length of wood (called the "mallet") to drive the tattooing points into the skin. The handle and mallet were generally made of wood while the points, either single, grouped or arranged to form a comb were made of Citrus thorns, fish bone, bone, teeth and turtle and oyster shells.[7][11][9][12]

Ancient tattooing traditions have also been documented among Papuans and Melanesians, with their use of distinctive obsidian skin piercers. Some archeological sites with these implements are associated with the Austronesian migration into Papua New Guinea and Melanesia. But other sites are older than the Austronesian expansion, being dated to around 1650 to 2000 BCE, suggesting that there was a preexisting tattooing tradition in the region.[9][13]

Among other ethnic groups, tattooing was also traditionally practiced among the Ainu people of Japan;[14] some Austroasians of Indochina;[15] Berber women of Tamazgha (North Africa);[16] the Yoruba, Fulani and Hausa people of Nigeria;[17] Native Americans of the Pre-Columbian Americas;[18][19][20] and the Welsh and Picts of Iron Age Britain.[21]

Traditional practices by regions

North America

Indigenous peoples of North America have a long history of tattooing. Tattooing was not a simple marking on the skin: it was a process that highlighted cultural connections to Indigenous ways of knowing and viewing the world, as well as connections to family, society, and place.[22]: xii

There is no way to determine the actual origin of tattooing for Indigenous people of North America.[23]: 44 The oldest known physical evidence of tattooing in North America was made through the discovery of a frozen, mummified, Inuit female on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska who had tattoos on her skin.[24]: 434 Through radiocarbon dating of the tissue, scientists estimated that the female came from the 16th century.[24]: 434 Until recently, archeologists have not prioritized the classification of tattoo implements when excavating known historic sites.[23]: 65 Recent review of materials found from the Mound Q excavation site point towards elements of tattoo bundles that are from pre-colonization times.[23]: 66–68 Scholars explain that the recognition of tattoo implements is significant because it highlights the cultural importance of tattooing for Indigenous People.[23]: 72

.jpg.webp)

Early explorers to North America made many ethnographic observations about the Indigenous people they met. Initially, they did not have a word for tattooing and instead described the skin modifications as "pounce, prick, list, mark, and raze" to "stamp, paint, burn, and embroider."[25]: 3 In 1585–1586, Thomas Harriot, who was part of the Grenville Expedition, was responsible for making observations about Indigenous People of North America.[26] In A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, Harriot recorded that some Indigenous people had their skin dyed and coloured.[26]: 11 John White provided visual representations of Indigenous people in the form of drawings and paintings.[26]: 46–81 Harriot and White also provided information highlighting specific markings seen on Indigenous chiefs during that time.[26]: 74 In 1623, Gabriel Sagard was a missionary who described seeing men and women with tattoos on their skin.[27]: 145

The Jesuit Relations of 1652 describes tattooing among the Petun and the Neutrals:

But those who paint themselves permanently do so with extreme pain, using, for this purpose, needles, sharp awls, or piercing thorns, with which they perforate, or have others perforate, the skin. Thus they form on the face, the neck, the breast, or some other part of the body, some animal or monster, for instance, an Eagle, a Serpent, a Dragon, or any other figure which they prefer; and then, tracing over the fresh and bloody design some powdered charcoal, or other black coloring matter, which becomes mixed with the blood and penetrates within these perforations, they imprint indelibly upon the living skin the designed figures. And this in some nations is so common that in the one which we called the Tobacco, and in that which – on account of enjoying peace with the Hurons and with the Iroquois – was called Neutral, I know not whether a single individual was found, who was not painted in this manner, on some part of the body.[28]

From 1712 to 1717, Joseph François Lafitau, another Jesuit missionary, recorded how Indigenous people were applying tattoos to their skin and developed healing strategies in tattooing the jawline to treat toothaches.[29]: 33–36 Indigenous people had determined that certain nerves that were along the jawline connected to certain teeth, thus by tattooing those nerves, it would stop them from firing signals that led to toothaches.[29]: 35 Some of these early ethnographic accounts questioned the actual practice of tattooing and hypothesized that it could make people sick due to unsanitary approaches.[27]: 145

Scholars explain that the study of Indigenous tattooing is relatively new as it was initially perceived as behaviour for societies outside of the norm.[22]: xii The process of colonization introduced new views of what acceptable behaviour included, leading to the near erasure of the tattoo tradition for many nations.[30] However, through oral traditions, the information about tattoos and the actual practice of tattooing has persisted to present day.

St. Lawrence Iroquoians had used bones as tattooing needles.[31] In addition, turkey bone tattooing tools were discovered at an ancient Fernvale, Tennessee site, dated back to 3500–1600 BCE.[32]

Inuit

The Inuit have a deep history of tattooing. In Inuktitut, the Inuit language of the eastern Canadian Arctic, the word kakiniit translates to the English word for tattoo[33]: 196 and the word tunniit means face tattoo.[30] Among the Inuit, some tattooed female faces and parts of the body symbolize a girl transitioning into a woman, coinciding with the start of her first menstrual cycle.[33]: 197 [30] A tattoo represented a woman's beauty, strength, and maturity.[33]: 197 This was an important practice because some Inuit believed that a woman could not transition into the spirit world without tattoos on her skin.[30] The Inuit have oral traditions that describe how the raven and the loon tattooed each other giving cultural significance to both the act of tattooing and the role of those animals in Inuit culture and history.[33]: 10 European missionaries colonized the Inuit in the beginning of the 20th century and associated tattooing as an evil practice[33]: 196 "demonizing" anyone who valued tattoos.[30] Alethea Arnaquq-Baril has helped Inuit women to revitalize the practice of traditional face tattoos through the creation of the documentary Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos, where she interviews elders from different communities asking them to recall their own elders and the history of tattoos.[30] The elders were able to recall the traditional practice of tattooing which often included using a needle and thread and sewing the tattoo into the skin by dipping the thread in soot or seal oil, or through skin poking using a sharp needle point and dipping it into soot or seal oil.[30] Hovak Johnston has worked with the elders in her community to bring the tradition of kakiniit back by learning the traditional ways of tattooing and using her skills to tattoo others.[34]

Osage Nation

The Osage people used tattooing for a variety of different reasons. The tattoo designs were based on the belief that people were part of the larger cycle of life and integrated elements of the land, sky, water, and the space in between to symbolize these beliefs.[35]: 222–228 In addition, the Osage People believed in the smaller cycle of life, recognizing the importance of women giving life through childbirth and men removing life through warfare.[35]: 216 Osage men were often tattooed after accomplishing major feats in battle, as a visual and physical reminder of their elevated status in their community.[35]: 223 Some Osage women were tattooed in public as a form of a prayer, demonstrating strength and dedication to their nation.[35]: 223

Haudenosaunee Confederation

The people of the Haudenosaunee Confederation historically used tattooing in connection to war. A tradition for many young men was to go on a journey into the wilderness, fast from eating any food, and discover who their personal manitou was.[36] : 97 Scholars explain that this process of discovery likely included dreams and visions that would bring a specific manitou to the forefront for each young man to have.[36]: 97 The manitou became an important element of protection during warfare and many boys tattooed their manitou onto their body to symbolize cultural significance of the manitou to their lives.[36]: 109 As they showed success in warfare, male warriors had more tattoos, some even keeping score of all the kills they had made.[36]: 112 Some warriors had tattoos on their faces that tallied how many people they had scalped in their lifetime.[36]: 115

Central America

A Spanish expedition led by Gonzalo de Badajoz in 1515 across what is today Panama ran into a village where prisoners from other tribes had been marked with tattoos.

[The Spaniards] found, however, some slaves who were branded in a painful fashion. The natives cut lines in the faces of the slaves, using a sharp point either of gold or of a thorn; they then fill the wounds with a kind of powder dampened with black or red juice, which forms an indelible dye and never disappears. The Spaniards took these slaves with them. It seems that this juice is corrosive and produces such terrible pain that the slaves are unable to eat on account of their sufferings.

— Peter Martyr, Decade III, Book X

China

Cemeteries throughout the Tarim Basin (Xinjiang of western China) including the sites of Qäwrighul, Yanghai, Shengjindian, Zaghunluq, and Qizilchoqa have revealed several tattooed mummies with Western Asian/Indo-European physical traits and cultural materials. These date from between 2100 and 550 BC.[3]

In ancient China, tattoos were considered a barbaric practice associated with the Yue peoples of southeastern and southern China. Tattoos were often referred to in literature depicting bandits and folk heroes. As late as the Qing dynasty, it was common practice to tattoo characters such as 囚 ("Prisoner") on convicted criminals' faces. Although relatively rare during most periods of Chinese history, slaves were also sometimes marked to display ownership.

However, tattoos seem to have remained a part of southern culture. Marco Polo wrote of Quanzhou, "Many come hither from Upper India to have their bodies painted with the needle in the way we have elsewhere described, there being many adepts at this craft in the city". At least three of the main characters – Lu Zhishen, Shi Jin (史進), and Yan Ching (燕青) – in the classic novel Water Margin are described as having tattoos covering nearly all of their bodies. Wu Song was sentenced to a facial tattoo describing his crime after killing Xi Menqing (西門慶) to avenge his brother. In addition, Chinese legend claimed the mother of Yue Fei (a famous Song general) tattooed the words "Repay the Country with Pure Loyalty" (精忠報國, jing zhong bao guo) down her son's back before he left to join the army.

Japan

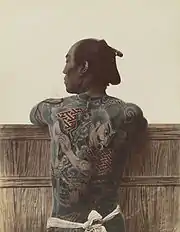

Tattooing for spiritual and decorative purposes in Japan is thought to extend back to at least the Jōmon or Paleolithic period and was widespread during various periods for both the Yamato and native Jomon groups. Chinese texts from before 300 AD described social differences among Japanese people as being indicated through tattooing and other bodily markings.[37] Chinese texts from the time also described Japanese men of all ages as decorating their faces and bodies with tattoos.[38]

Between 1603 and 1868, Japanese tattooing was only practiced by the ukiyo (floating world) subculture. Generally firemen, manual workers and prostitutes wore tattoos to communicate their status. By the early 17th century, criminals were widely being tattooed as a visible mark of punishment. Criminals were marked with symbols typically including crosses, lines, double lines and circles on certain parts of the body, mostly the face and arms. These symbols sometimes designated the places where the crimes were committed. In one area, the character for "dog" was tattooed on the criminal's forehead.[38]: 77 [39]

The Government of Meiji Japan, formed in 1868, banned the art of tattooing altogether, viewing it as barbaric and lacking respectability. This subsequently created a subculture of criminals and outcasts. These people had no place in "decent society" and were frowned upon. They could not simply integrate into mainstream society because of their obvious visible tattoos, forcing many of them into criminal activities which ultimately formed the roots for the modern Japanese mafia, the Yakuza, with which tattoos have become almost synonymous in Japan.

_P.81.png.webp)

The Ainu people also participate in tattooing called Sinuye. These are connected with the Kamuy, gods of the ainu culture. Women receive tattoos around their mouths at an early age, the tattooing continues until they are married. Men may receive tattoos as well, most commonly on the shoulders or arms.

Thailand and Cambodia

Thai-Khmer tattoos, also known as Yantra tattooing, was common since ancient times. Just as other native southeast Asian cultures, animistic tattooing was common in Tai tribes that were is southern China. Over time, this animistic practice of tattooing for luck and protection assimilated Hindu and Buddhist ideas. The Sak Yant traditional tattoo is practiced today by many and are usually given either by a Buddhist monk or a Brahmin priest. The tattoos usually depict Hindu gods and use the Mon script or ancient Khmer script, which were the scripts of the classical civilizations of mainland southeast Asia.

Taiwan

In Taiwan, facial tattoos of the Atayal people are called ptasan; they are used to demonstrate that an adult man can protect his homeland, and that an adult woman is qualified to weave cloth and perform housekeeping.[40]

Taiwan is believed to be the homeland of all the Austronesian peoples,[41][42] which includes Filipinos, Indonesians, Polynesians and Malagasy peoples, all with strong tattoo traditions. This along with the striking correlation between Austronesian languages and the use of the so-called hand-tapping method suggests that Austronesian peoples inherited their tattooing traditions from their ancestors established in Taiwan or along the southern coast of the Chinese mainland.[43]

Philippines

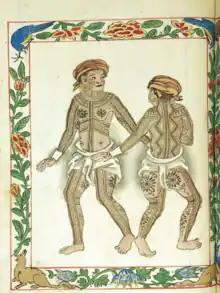

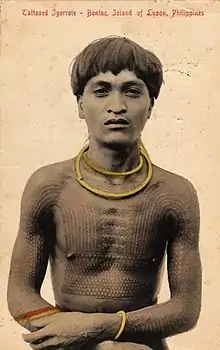

Tattooing (batok) on both sexes was practiced by almost all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands during the pre-colonial era, like in other Austronesian groups.[44][45][46][47] Ancient clay human figurines found in archaeological sites in the Batanes Islands, around 2500 to 3000 years old, have simplified stamped-circle patterns, which are believed to represent tattoos and possibly branding (also commonly practiced) as well. [48] Excavations at the Arku Cave burial site in Cagayan Province in northern Luzon have also yielded both chisel and serrated-type heads of possible hafted bone tattoo instruments alongside Austronesian material culture markers like adzes, spindle whorls, barkcloth beaters, and lingling-o jade ornaments. These were dated to before 1500 BCE and are remarkably similar to the comb-type tattoo chisels found throughout Polynesia.[49][50][51][52]

_(1887).png.webp)

Ancient tattoos can also be found among mummified remains of various Igorot peoples in cave and hanging coffin burials in northern Luzon, with the oldest surviving examples of which going back to the 13th century. The tattoos on the mummies are often highly individualized, covering the arms of female adults and the whole body of adult males. A 700 to 900-year-old Kankanaey mummy in particular, nicknamed "Apo Anno", had tattoos covering even the soles of the feet and the fingertips. The tattoo patterns are often also carved on the coffins containing the mummies.[50]

When Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan expedition (c. 1521) first encountered the Visayans of the islands, he repeatedly described them as "painted all over."[53] The original Spanish name for the Visayans, "Los Pintados" ("The Painted Ones") was a reference to their tattoos.[44][45][54]

"Besides the exterior clothing and dress, some of these nations wore another inside dress, which could not be removed after it was once put on. These are the tattoos of the body so greatly practiced among Visayans, whom we call Pintados for that reason. For it was custom among them, and was a mark of nobility and bravery, to tattoo the whole body from top to toe when they were of an age and strength sufficient to endure the tortures of the tattooing which was done (after being carefully designed by the artists, and in accordance with the proportion of the parts of the body and the sex) with instruments like brushes or small twigs, with very fine points of bamboo." "The body was pricked and marked with them until blood was drawn. Upon that a black powder or soot made from pitch, which never faded, was put on. The whole body was not tattooed at one time, but it was done gradually. In olden times no tattooing was begun until some brave deed had been performed; and after that, for each one of the parts of the body which was tattooed some new deed had to be performed. The men tattooed even their chins and about the eyes so that they appeared to be masked. Children were not tattooed, and the women only one hand and part of the other. The Ilocanos in this island of Manila also tattooed themselves but not to the same extent as the Visayans."

— Francisco Colins, Labor Evangelica (1663), [44]

Tattoos were known as batuk (or batok) or patik among the Visayan people; batik, buri, or tatak (compare with Samoan tatau) among the Tagalog people; buri among the Pangasinan, Kapampangan, and Bicolano people; batek, butak, or burik among the Ilocano people; batek, batok, batak, fatek, whatok (also spelled fatok), or buri among the various Igorot peoples;[44][45][55] and pangotoeb (also spelled pa-ngo-túb, pengeteb, or pengetev) among the various Manobo peoples.[56][57] These terms were also applied to identical designs used in woven textiles, pottery, and decorations for shields, tool and weapon handles, musical instruments, and others.[44][45][55] Most of the names are derived from Proto-Austronesian *beCik ("tattoo") and *patik ("mottled pattern").[58][59]

_(14761627334).jpg.webp)

Affixed forms of these words were used to describe tattooed people, often as a synonym for "renowned/skilled person"; like Tagalog batikan, Visayan binatakan, and Ilocano burikan. Men without tattoos were distinguished as puraw among Visayans, meaning "unmarked" or "plain" (compare with Samoan pulaʻu). This was only socially acceptable for children and adolescents, as well as the asog (feminized men, usually shamans); otherwise being a puraw adult usually identified someone as having very low status.[44][45] In contrast, tattoos in other ethnic groups (like the Manobo people) were optional, and no words that distinguished tattooed and non-tattooed individuals exist in their languages. Though when tattoos are present, they are still have to follow various traditional rules when it comes to placement and design.[56]

Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status. They were also believed to have magical or apotropaic abilities, and can also document personal or communal history. Their design and placement varied by ethnic group, affiliation, status, and gender. They ranged from almost completely covering the body, including tattoos on the face meant to evoke frightening masks among the elite warriors of the Visayans; to being restricted only to certain areas of the body like Manobo tattoos which were only done on the forearms, lower abdomen, back, breasts, and ankles.[44][45][55][56]

They were commonly repeating geometric designs (lines, zigzags, repeating shapes); stylized representations of animals (like snakes, lizards, dogs, frogs, or giant centipedes), plants (like grass, ferns, or flowers), or humans; or star-like and sun-like patterns. Each motif had a name, and usually a story or significance behind it, though most of them have been lost to time. They were the same patterns and motifs used in other artforms and decorations of the particular ethnic groups they belong to. Tattoos were, in fact, regarded as a type of clothing in itself, and men would commonly wear only loincloths (bahag) to show them off.[44][45][50][55][56][60]

.jpg.webp)

"The principal clothing of the Cebuanos and all the Visayans is the tattooing of which we have already spoken, with which a naked man appears to be dressed in a kind of handsome armor engraved with very fine work, a dress so esteemed by them they take it for their proudest attire, covering their bodies neither more nor less than a Christ crucified, so that although for solemn occasions they have the marlotas (robes) we mentioned, their dress at home and in their barrio is their tattoos and a bahag, as they call that cloth they wrap around their waist, which is the sort the ancient actors and gladiators used in Rome for decency's sake."

Tattoos are acquired gradually over the years, and patterns can take months to complete and heal. The tattooing process were sacred events that involved rituals to ancestral spirits (anito) and the heeding of omens. For example, if the artist or the recipient sneezes before a tattooing, it was seen as a sign of disapproval by the spirits, and the session was called off or rescheduled. Artists were usually paid with livestock, heirloom beads, or precious metals. They were also housed and fed by the family of the recipient during the process. A celebration was usually held after a completed tattoo.[45][44][50]

Tattoos were made by skilled artists using the distinctively Austronesian hafted tattooing technique. This involves using a small hammer to tap the tattooing needle (either a single needle or a brush-like bundle of needles) set perpendicular to a wooden handle in an L-shape (hence "hafted"). This handle makes the needle more stable and easier to position. The tapping moves the needle in and out of the skin rapidly (around 90 to 120 taps a minute). The needles were usually made from wood, horn, bone, ivory, metal, bamboo, or citrus thorns. The needles created wounds on the skin that were then rubbed with the ink made from soot or ashes mixed with water, oil, plant extracts (like sugarcane juice), or even pig bile. The artists also commonly traced an outline of the designs on the skin with the ink, using pieces of string or blades of grass, prior to tattooing. In some cases, the ink was applied before the tattoo points are driven into the skin. Most tattoo practitioners were men, though female practitioners also existed. They were either residents to a single village or traveling artists who visited different villages.[44][45][50][55]

Another tattooing technique predominantly practiced by the Lumad and Negrito peoples uses a small knife or a hafted tattooing chisel to quickly incise the skin in small dashes. The wounds are then rubbed with pigment. They differ from the techniques which use points in that the process also produces scarification. Regardless, the motifs and placements are very similar to the tattoos made with hafted needles.[56]

Tattooing traditions were lost as Filipinos were converted to Christianity during the Spanish colonial era. Tattooing were also lost in some groups (like the Tagalog and the Moro people) shortly before the colonial period due to their (then recent) conversion to Islam. It survived until around the 19th to the mid-20th centuries in more remote areas of the Philippines, but also fell out of practice due to modernization and western influence. Today, it is a highly endangered tradition and only survives among some members of the Igorot people of the Luzon highlands,[44] some Lumad people of the Mindanao highlands,[56] and the Sulodnon people of the Panay highlands.[46][61]

Malaysia and Indonesia

Several tribes in the insular parts have tattooing in their culture. One notable example is the Dayak people of Kalimantan in Borneo (Bornean traditional tattooing). Another ethnic group that practices tattooing are the Mentawai people, as well as Moi and Meyakh people in West Papua.[62]

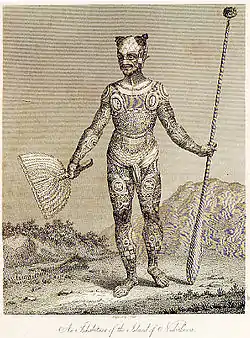

Solomon Islands

Some artifacts dating back 3,000 years from the Solomon Islands may have been used for tattooing human skin. Obsidian pieces have been duplicated, then used to conduct tattoos on pig skin, then compared to the original artifacts. "They conducted these experiments to observe the wear, such as chipping and scratches, and residues on the stones caused by tattooing, and then compared that use-wear with 3,000 year old artifacts. They found that the obsidian pieces, old and new, show similar patterns, suggesting that they hadn't been used for working hides, but were for adorning human skin."[63]

Marquesas Islands

New Zealand

The Māori people of New Zealand practised a form of tattooing known as tā moko, traditionally created with chisels.

However, from the late 20th century onward, there has been a resurgence of tā moko taking on European styles amongst Maori. Traditional tā moko was reserved for head area. There is also a related tattoo art, kirituhi, which has a similar aesthetic to tā moko but is worn by non-Maori.

Samoa

The traditional male tattoo in Samoa is called the pe'a. The traditional female tattoo is called the malu. The word tattoo is believed to have originated from the Samoan word tatau, coming from Proto-Oceanic *sau₃ referring to a wingbone from a flying fox used as an instrument for the tattooing process.[64] When the Samoan Islands were first seen by Europeans in 1722 three Dutch ships commanded by Jacob Roggeveen visited the eastern island known as Manua. A crew member of one of the ships described the natives in these words, "They are friendly in their speech and courteous in their behavior, with no apparent trace of wildness or savagery. They do not paint themselves, as do the natives of some other islands, but on the lower part of the body they wear artfully woven silk tights or knee breeches. They are altogether the most charming and polite natives we have seen in all of the South Seas..."

The ships lay at anchor off the islands for several days, but the crews did not venture ashore and did not even get close enough to the natives to realize that they were not wearing silk leggings, but their legs were completely covered in tattoos.

In Samoa, the tradition of applying tattoo, or tatau, by hand has been unbroken for over two thousand years. Tools and techniques have changed little. The skill is often passed from father to son, each tattoo artist, or tufuga, learning the craft over many years of serving as his father's apprentice. A young artist-in-training often spent hours, and sometimes days, tapping designs into sand or tree bark using a special tattooing comb, or au. Honoring their tradition, Samoan tattoo artists made this tool from sharpened boar's teeth fastened together with a portion of the turtle shell and to a wooden handle.

Traditional Samoan tattooing of the "pe'a", body tattoo, is an ordeal that is not lightly undergone. It takes many weeks to complete. The process is very painful and used to be a necessary prerequisite to receiving a matai title; this however is no longer the case. Tattooing was also a very costly procedure.

Samoan society has long been defined by rank and title, with chiefs (ali'i) and their assistants, known as talking chiefs (tulafale). The tattooing ceremonies for young chiefs, typically conducted at the time of puberty, were part of their ascendance to a leadership role. The permanent marks left by the tattoo artists would forever celebrate their endurance and dedication to cultural traditions. The pain was extreme and the risk of death by infection was a concern; to back down from tattooing was to risk being labeled a "pala'ai" or coward. Those who could not endure the pain and abandoned their tattooing were left incomplete, would be forced to wear their mark of shame throughout their life. This would forever bring shame upon their family so it was avoided at all cost.

The Samoan tattooing process used a number of tools which remained almost unchanged since their first use. "Autapulu" is a wide tattooing comb used to fill in the large dark areas of the tattoo. "Ausogi'aso tele" is a comb used for making thick lines. "Ausogi'aso laititi" is a comb used for making thin lines. "Aumogo" small comb is used for making small marks. "Sausau" is the mallet used for striking the combs. It is almost two feet in length and made from the central rib of a coconut palm leaf. "Tuluma" is the pot used for holding the tattooing combs. Ipulama is the cup used for holding the dye. The dye is made from the soot collected from burnt lama nuts. "Tu'I" used to grind up the dye. These tools were primarily made out of animal bones to ensure sharpness.

The tattooing process itself would be 5 sessions, in theory. These 5 sessions would be spread out over 10 days for the inflammation to subside.

Christian missionaries from the west attempted to purge tattooing among the Samoans, thinking it barbaric and inhumane. Many young Samoans resisted mission schools since they forbade them to wear tattoos. But over time attitudes relaxed toward this cultural tradition and tattooing began to reemerge in Samoan culture.

Europe

The earliest possible evidence for tattooing in Europe appears on ancient art from the Upper Paleolithic period as incised designs on the bodies of humanoid figurines.[65] The Löwenmensch figurine from the Aurignacian culture dates to approximately 40,000 years ago[66] and features a series of parallel lines on its left shoulder. The ivory Venus of Hohle Fels, which dates to between 35,000 and 40,000 years ago[67] also exhibits incised lines down both arms, as well as across the torso and chest.

The oldest and most famous direct proof of ancient European tattooing appears on the body of Ötzi the Iceman, who was found in the Ötz valley in the Alps and dates from the late 4th millennium BC.[3] Studies have revealed that Ötzi had 61 carbon-ink tattoos consisting of 19 groups of lines simple dots and lines on his lower spine, left wrist, behind his right knee and on his ankles. It has been argued that these tattoos were a form of healing because of their placement, though other explanations are plausible.[68]

The Picts may have been tattooed (or scarified) with elaborate, war-inspired black or dark blue woad (or possibly copper for the blue tone) designs. Julius Caesar described these tattoos in Book V of his Gallic Wars (54 BC). Nevertheless, these may have been painted markings rather than tattoos.[69]

In his encounter with a group of pagan Scandinavian Rus' merchants in the early 10th century, Ahmad ibn Fadlan describes what he witnesses among them, including their appearance. He notes that the Rus' were heavily tattooed: "From the tips of his toes to his neck, each man is tattooed in dark green with designs, and so forth."[70] Raised in the aftermath of the Norman conquest of England, William of Malmesbury describes in his Gesta Regum Anglorum that the Anglo-Saxons were tattooed upon the arrival of the Normans (..."arms covered with golden bracelets, tattooed with coloured patterns ...").[71]

The significance of tattooing was long open to Eurocentric interpretations. In the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann, while arguing against painting the interior of Parisian churches, said the practice "reminds me of the tattoos used in place of clothes by barbarous peoples to conceal their nakedness".[72]

Greece and Rome

Greek written records of tattooing date back to at least the 5th-century BCE.[3]: 19 The ancient Greeks and Romans used tattooing to penalize slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war. While known, decorative tattooing was looked down upon and religious tattooing was mainly practiced in Egypt and Syria.[73]: 155 According to Robert Graves in his book The Greek Myths, tattooing was common amongst certain religious groups in the ancient Mediterranean world, which may have contributed to the prohibition of tattooing in Leviticus. In 316, emperor Constantine I made it illegal to tattoo the face of slaves as punishment.[74] The Romans of Late Antiquity also tattooed soldiers and arms manufacturers, a practice that continued into the ninth century.[73]: 155

The Greek verb stizein (στίζειν), meaning "to prick," was used for tattooing. Its derivative stigma (στίγμα) was the common term for tattoo marks in both Greek and Latin.[73]: 142 During the Byzantine period, the verb kentein (κεντεῖν) replaced stizein, and a variety of new Latin terms replaced stigmata including signa "signs," characteres "stamps," and cicatrices "scars."[73]: 154–155

Scythia

Tattooed mummies dating to c. 500 BC were extracted from burial mounds on the Ukok plateau during the 1990s. Their tattooing involved animal designs carried out in a curvilinear style. The Man of Pazyryk, a Scythian chieftain, is tattooed with an extensive and detailed range of fish, monsters and a series of dots that lined up along the spinal column (lumbar region) and around the right ankle.

Egypt and Nubia

Despite a lack of direct textual references, tattooed human remains and iconographic evidence indicate that ancient Egyptians practiced tattooing from at least 2000 BCE.[75][76]: 86, 89 It is theorized that tattooing entered Egypt through Nubia,[77]: 23 but this claim is complicated by the high mobility between Lower Nubia and Upper Egypt as well as Egypt's annexation of Lower Nubia during the Middle Kingdom.[76]: 92 Archeologist Geoffrey J. Tassie argues that it may be more appropriate to classify tattoo in ancient Egypt and Nubia as part of a larger Nile Valley tradition.[76]: 93

The most famous tattooed mummies from this region are Amunet, a priestess of Hathor, and two Hathoric dancers from Dynasty XI that were found at Deir el-Bahari.[76]: 90 In 1898, Daniel Fouquet, a medical doctor from Cairo, wrote an article on medical tattooing practices in ancient Egypt[78] in which he describes the tattoos on these three mummies and speculates that they may have served a medicinal or therapeutic purpose: "The examination of these scars, some white, others blue, leaves in no doubt that they are not, in essence, ornament, but an established treatment for a condition of the pelvis, very probably chronic pelvic peritonitis."[79]

Ancient Egyptian tattooing appears to have been practiced on women exclusively; with an exception of a pre-dynastic male mummy found with

“Dark smudges on his arm, appearing as faint markings under natural light, had remained unexamined. Infrared photography recently revealed that these smudges were in fact tattoos of two slightly overlapping horned animals. The horned animals have been tentatively identified as a wild bull (long tail, elaborate horns) and a Barbary sheep (curving horns, humped shoulder). Both animals are well known in Predynastic Egyptian art. The designs are not superficial and have been applied to the dermis layer of the skin, the pigment was carbon-based, possibly some kind of soot.”

[80] constituting the oldest known figural tattoo.[80] And the possible exception of one extremely worn Dynasty XII stele, there is no artistic or physical evidence that men were commonly tattooed.[77] However, by the Meroitic Period (300 BCE – 400 CE), it was practiced on Nubian men as well.[76]: 88

Accounts of early travelers to ancient Egypt describe the tool used as an uneven number of metal needles attached to a wooden handle.[76]: 86–87 [81]

Two well-preserved Egyptian mummies from 4160 B.C.E., a priestess and a temple dancer for the fertility goddess Hathor, bear random-dot and dash tattoo patterns on the lower abdomen, thighs, arms, and chest.[82]

Copts

.jpg.webp)

Coptic tattoos often consist of three lines, three dots and two elements, reflecting the Trinity. The tools used had an odd number of needles to bring luck and good fortune.[76]: 87 Many Copts have the Coptic cross tattooed on the inside of their right arm.[83][73]: 145 This may have been influenced by a similar practice tattooing religious symbols on the wrists and arms during the Ptolemaic period.[76]: 91

Persia

Herodotus' writings suggest that slaves and prisoners of war were tattooed in Persia during the classical era. This practice spread from Persia to Greece and then to Rome.[73]: 146–147, 155

The most famous depiction of tattooing in Persian literature goes back 800 years to a tale by Rumi about a man who is proud to want a lion tattoo but changes his mind once he experiences the pain of the needle.[84]

In the hamam (the baths), there were dallaks whose job was to help people wash themselves. This was a notable occupation because apart from helping the customers with washing, they were massage-therapists, dentists, barbers and tattoo artists.[85]

Modern world tattooing practices

Pilgrimage

British and other pilgrims to the Holy Lands throughout the 17th century were tattooed with the Jerusalem cross to commemorate their voyages,[86] including William Lithgow in 1612.[87]

"Painted Prince"

Perhaps the most famous tattooed foreigner in Europe prior to the voyages of James Cook was the "Painted Prince" - a slave named "Jeoly" from Mindanao in the Philippines. He was initially bought with his mother (who died of illness shortly afterwards) from a Mindanaoan slave trader in Mindanao in 1690 by a "Mister Moody", who passed Jeoly on to the English explorer William Dampier. Dampier described Jeoly's intricate tattoos in his journals:[89][90][91]

He was painted all down the Breast, between his Shoulders behind; on his Thighs (mostly) before; and the Form of several broad Rings, or Bracelets around his Arms and Legs. I cannot liken the Drawings to any Figure of Animals, or the like; but they were very curious, full of great variety of Lines, Flourishes, Chequered-Work, &c. keeping a very graceful Proportion, and appearing very artificial, even to Wonder, especially that upon and between his Shoulder-blades […] I understood that the Painting was done in the same manner, as the Jerusalem Cross is made in Mens Arms, by pricking the Skin, and rubbing in a Pigment.

— William Dampier, A New Voyage Around the World (1697)

Jeoly told Dampier that he was the son of a rajah in Mindanao, and told him that gold (bullawan) was very easy to find in his island. Jeoly also mentioned that the men and women of Mindanao were also tattooed similarly, and that his tattoos were done by one of his five wives.[89] Some authors believe him to be a Visayan pintado. Visayan people are a Philippine ethnolinguistic group native to the Visayas, the southernmost islands of Luzon and a significant portion of Mindanao that speak Binisaya language. Other authors claimed Jeoly is Palauan due to the pattern of his tattoos and his account that he was tattooed by women (Palauan tattooists were female).[92] However, the pattern of his tattoos are very similar to all Batok in recorded history and it is a known fact that tattooing can be done by women tattoo artists like Apo Whang-od, the last surviving mambabatok.

Dampier brought Jeoly with him to London, intending to recoup the money he lost while at sea by displaying Jeoly to curious crowds. Dampier invented a fictional backstory for him, renaming him "Prince Giolo" and claiming that he was the son and heir of the "King of Gilolo." Instead of being from Mindanao, Dampier now claimed that he was only shipwrecked in Mindanao with his mother and sister, whereupon he was captured and sold into slavery. Dampier also claimed that Jeoly's tattoos were created from an "herbal paint" that rendered him invulnerable to snake venom, and that the tattooing process was done naked in a room of venomous snakes.[89][93] Dampier initially toured around with Jeoly, showing his tattoos to large crowds. Eventually, Dampier sold Jeoly to the Blue Boar Inn in Fleet Street. Jeoly was displayed as a sideshow by the inn, with his likeness printed on playbills and flyers advertising his "exquisitely painted" body. By this time, Jeoly had contracted smallpox and was very ill. He was later brought to the University of Oxford for examination, but he died shortly afterwards of smallpox at around thirty years of age in the summer of 1692. His tattooed skin was preserved and was displayed in the Anatomy School of Oxford for a time, although it was lost prior to the 20th century.[89][93][94]

Cook's expedition

Between 1766 and 1779, Captain James Cook made three voyages to the South Pacific, the last trip ending with Cook's death in Hawaii in February 1779. When Cook and his men returned home to Europe from their voyages to Polynesia, they told tales of the 'tattooed savages' they had seen. The word "tattoo" itself comes from the Tahitian tatau, and was introduced into the English language by Cook's expedition (though the word 'tattoo' or 'tap-too', referring to a drumbeat, had existed in English since at least 1644)[95]

It was in Tahiti aboard the Endeavour, in July 1769, that Cook first noted his observations about the indigenous body modification and is the first recorded use of the word tattoo to refer to the permanent marking of the skin. In the ship's log book recorded this entry: "Both sexes paint their Bodys, Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins, in such a manner as to be indelible." Cook went on to write, "This method of Tattowing I shall now describe...As this is a painful operation, especially the Tattowing of their Buttocks, it is performed but once in their Lifetimes."

Cook's Science Officer and Expedition Botanist, Sir Joseph Banks, returned to England with a tattoo. Banks was a highly regarded member of the English aristocracy and had acquired his position with Cook by putting up what was at the time the princely sum of some ten thousand pounds in the expedition. In turn, Cook brought back with him a tattooed Raiatean man, Omai, whom he presented to King George and the English Court. Many of Cook's men, ordinary seamen and sailors, came back with tattoos, a tradition that would soon become associated with men of the sea in the public's mind and the press of the day.[96] In the process, sailors and seamen re-introduced the practice of tattooing in Europe, and it spread rapidly to seaports around the globe.

"Reintroduction" to the Western world

The popularity of modern Western tattooing owes its origins in large part to Captain James Cook's voyages to the South Pacific in the 1770s, but since the 1950s a false belief has persisted that modern Western tattooing originated exclusively from these voyages.[97]: 16 [98] Tattooing has been consistently present in Western society from the modern period stretching back to Ancient Greece,[65][99] though largely for different reasons. A long history of European tattoo predated these voyages, including among sailors and tradesmen, pilgrims visiting the Holy Land,[38]: 150–151 [100][101]: 362, 366, 379–380 and on Europeans living among Native Americans.[102] European sailors have practiced tattooing since at least the 16th century (see sailor tattoos).[103]: xvii [104]: 19

Tattoo historian Anna Felicity Friedman suggests a couple reasons for the "Cook Myth".[97]: 18–20 First, modern European words for the practice (e.g., "tattoo", "tatuaje", "tatouage", "Tätowierung", and "tatuagem") derive from the Tahitian word "tatau", which was introduced to European languages through Cook's travels. However, prior European texts show that a variety of metaphorical terms were used for the practice, including "pricked," "marked", "engraved," "decorated," "punctured," "stained," and "embroidered." Friedman also points out that the growing print culture at the time of Cook's voyages may have increased the visibility of tattooing despite its prior existence in the West.

19th century Europe

By the 19th century, tattooing had spread to British society but was still largely associated with sailors[105] and the lower or even criminal class.[106] Tattooing had however been practised in an amateur way by public schoolboys from at least the 1840s[107][108] and by the 1870s had become fashionable among some members of the upper classes, including royalty.[109][110] In its upmarket form, it could be a lengthy, expensive[111] and sometimes painful[112] process.

Tattooing spread among the upper classes all over Europe in the 19th century, but particularly in Britain where it was estimated in Harmsworth Magazine in 1898 that as many as one in five members of the gentry were tattooed. Taking their lead from the British Court, where George V followed Edward VII's lead in getting tattooed; King Frederick IX of Denmark, the King of Romania, Kaiser Wilhelm II, King Alexander of Yugoslavia and even Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, all sported tattoos, many of them elaborate and ornate renditions of the Royal Coat of Arms or the Royal Family Crest. King Alfonso XIII of modern Spain also had a tattoo.

The perception that there is a marked class division on the acceptability of the practice has been a popular media theme in Britain, as successive generations of journalists described the practice as newly fashionable and no longer for a marginalised class. Examples of this cliché can be found in every decade since the 1870s.[113] Despite this evidence, a myth persists that the upper and lower classes find tattooing attractive and the broader middle classes rejecting it.

20th century Europe

In 1969, the House of Lords debated a bill to ban the tattooing of minors, on grounds it had become "trendy" with the young in recent years but was associated with crime. It was noted that 40 per cent of young criminals had tattoos and that marking the skin in this way tended to encourage self-identification with criminal groups. Two peers, Lord Teynham and the Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair however rose to object that they had been tattooed as youngsters, with no ill effects.[114] Since the 1970s, tattoos have become more socially acceptable and fashionable among celebrities.[115] Tattoos are less prominent on figures of authority, and the practice of tattooing by the elderly is still considered remarkable. In recent history, authority figures have adopted the trend more widely; in Australia 65% of people in these professions are tattooed.[116]

19th century United States

The first documented professional tattooer in the United States was Martin Hildebrandt, who had enlisted in the United States Navy in the late 1840s where he learned to tattoo,[117] served as a soldier in the American Civil War,[118] and opened a shop in New York City in the early 1870s.[119] The first documented professional tattooist (with a permanent studio, working on members of the paying public) in Britain was Sutherland Macdonald in the early 1880s. Tattooing was an expensive and painful process and by the late 1880s had become a mark of wealth for the crowned heads of Europe.[120]

In 1891, New York City tattooer Samuel O'Reilly patented the first electric tattoo machine, a modification of Thomas Edison's electric pen.

The earliest appearance of tattoos on women during this period were in the circus in the late 19th century. These "Tattooed Ladies" were covered – with the exception of their faces, hands, necks, and other readily visible areas – with various images inked into their skin. To lure the crowd, the earliest ladies, like Betty Broadbent and Nora Hildebrandt told tales of captivity; they usually claimed to have been taken hostage by Native Americans that tattooed them as a form of torture. However, by the late 1920s the sideshow industry was slowing and by the late 1990s the last tattooed lady was out of business.[121]

Tattooing in the early United States

In the period shortly after the American Revolution, to avoid impressment by British Navy ships, sailors used government issued protection papers to establish their American citizenship. However, many of the descriptions of the individual described in the seamen's protection certificates were so general, and it was so easy to abuse the system, that many impressment officers of the Royal Navy simply paid no attention to them. "In applying for a duplicate Seaman's Protection Certificate in 1817, James Francis stated that he 'had a protection granted him by the Collector of this Port on or about 12 March 1806 which was torn up and destroyed by a British Captain when at sea.'"[122]

One way of making them more specific and more effective was to describe a tattoo, which is highly personal as to subject and location, and thus use that description to precisely identify the seaman. As a result, many of the official certificates also carried information about tattoos and scars, as well as any other specific identifying information. This also perhaps led to an increase and proliferation of tattoos among American seamen who wanted to avoid impressment. During this period, tattoos were not popular with the rest of the country. "Frequently the "protection papers" made reference to tattoos, clear evidence that individual was a seafaring man; rarely did members of the general public adorn themselves with tattoos."[123]

"In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, tattoos were as much about self-expression as they were about having a unique way to identify a sailor's body should he be lost at sea or impressed by the British navy. The best source for early American tattoos is the protection papers issued following a 1796 congressional act to safeguard American seamen from impressment. These proto-passports catalogued tattoos alongside birthmarks, scars, race, and height. Using simple techniques and tools, tattoo artists in the early republic typically worked on board ships using anything available as pigments, even gunpowder and urine. Men marked their arms and hands with initials of themselves and loved ones, significant dates, symbols of the seafaring life, liberty poles, crucifixes, and other symbols."[124]

Sometimes, to protect themselves, the sailors requested not only that the tattoos be described, but that they would also be sketched out on the protection certificate as well. As one researched said, "Clerks writing the documents often sketched the tattoos as well as describing them."[125]

Russian gang culture

Within the gang cultures of the world, tattoos, along with piercings, are often associated with forms of art, identification, and allegiance to brotherhood. The gang culture in Russia offers an interesting example of the desire to connect through tattoos. Beginning in the latter days of Imperial Russia, the common experience of corporal punishment created a bond among both men and women within society. Corporal punishments often left flogging marks and other scars that marred inmates' bodies. With these mutilations, people became easily identifiable as Russian/Soviet criminals. These identifiable markers became a problem when some inmates ran away into Serbia. Inmates who fled tried to conceal their scars with tattoos to keep their identity secret. However, this wouldn't last long as the prisons started to use tattoos as a form of serial numbers identification for their inmates. This marking identity imposed on inmates by the prisons simultaneously created an anti-culture and a new gang culture. By the 1920s, as the Soviet union faced even more social class troubles, many of the Russian and Soviet criminals wanted to connect with the ideals and laws associated with past criminals. This created a boom of tattoos among prisoners, that by the late 1920s “about 60-70%” of all inmates had some type of Tattoo.[126] This new wave of tattoo among the Russian prisons were seen as a right of passage. Soviet tattoos often indicated a person's socio-demographic status, the crimes they have committed, the prisons they associated with, what drugs they had or used, and other habits.

Use of Tattoos in Indigenous boarding schools

Tattooing in the federal Indian boarding school system was commonly practiced during the 1960s and 1970s. Such tattoos often took the form of small markings or initials and were often used as a form of resistance; a way to reclaim one's body.

Due to the forced assimilation practices of the Western boarding schools, many indigenous cultural practices were on a severe decline, tattooing being one of them. As a way to retain their cultural heritage some students practiced this ritual and tattooed themselves with found materials like sewing needles and India Ink.

Within the schools, the authorities physically labeled the students: “a personal identification number was written in purple ink on their wrists and on the small cupboard in which their few belongings were stored.”[127] Oftentimes the students had a tendency to tattoo their initials on this very spot; the exact place where the school authorities first marked them. This can be seen as a strong act of resistance where the students were physically rejecting their numerical ID, and reclaiming their own body and identity.

The Tattoo Renaissance

Tattooing has steadily increased in popularity since the invention of the electric tattoo machine.[128][129] In 1936, 1 in 10 Americans had a tattoo of some form.[130] In the late 1950s, Tattoos were greatly influenced by several artists, in particular Lyle Tuttle, Cliff Raven, Don Nolan, Zeke Owens and Spider Webb. A second generation of artists, trained by the first, continued these traditions into the 1970s, and included artists such as Bob Roberts, Jamie Summers, Jack Rudy and Don Ed Hardy.[131]

Since the 1970s, tattoos have become a mainstream part of global and Western fashion, common among both sexes, to all economic classes, and to age groups from the later teen years to middle age. The decoration of blues singer Janis Joplin with a wristlet and a small heart on her left breast, by the San Francisco tattoo artist Lyle Tuttle, has been called a seminal moment in the popular acceptance of tattoos as art. Formal interest in the art of the tattoo became prominent in the 1970s through the beginning of the 21st century.[132] For many young Americans, the tattoo has taken on a decidedly different meaning than for previous generations. The tattoo has "undergone dramatic redefinition" and has shifted from a form of deviance to an acceptable form of expression.[133]

In 1988, scholar Arnold Rubin created a collection of works regarding the history of tattoo cultures, publishing them as the "Marks of Civilization".[134] In this, the term "Tattoo Renaissance" was coined, referring to a period marked by technological, artistic and social change.[129] Wearers of tattoos, as members of the counterculture began to display their body art as signs of resistance to the values of the white, heterosexual, middle-class.[135] The clientele changed from sailors, bikers, and gang members to the middle and upper class. There was also a shift in iconography from the badge-like images based on repetitive pre-made designs known as flash to customized full-body tattoo influenced by Polynesian and Japanese tattoo art, known as sleeves, which are categorized under the relatively new and popular avant-garde genre.[129] In the early 90s the designs of Leo Zulueta, "the father of modern tribal tattooing", became very popular.[136][137] Tattooers transformed into "Tattoo Artists": men and women with fine art backgrounds began to enter the profession alongside the older, traditional tattooists.

Tattoos have experienced a resurgence in popularity in many parts of the world, particularly in Europe, Japan, and North and South America. The growth in tattoo culture has seen an influx of new artists into the industry, many of whom have technical and fine arts training. Coupled with advancements in tattoo pigments and the ongoing refinement of the equipment used for tattooing, this has led to an improvement in the quality of tattoos being produced.[138]

Star Stowe (Miss February 1977) was the first Playboy Playmate with a visible tattoo on her centerfold.

During the 2000s, the presence of tattoos became evident within pop culture, inspiring television shows such as A&E's Inked and TLC's Miami Ink and LA Ink. In addition, many celebrities have made tattoos more acceptable in recent years.

Contemporary art exhibitions and visual art institutions have featured tattoos as art through such means as displaying tattoo flash, examining the works of tattoo artists, or otherwise incorporating examples of body art into mainstream exhibits. One such 2009 Chicago exhibition, Freaks & Flash, featured both examples of historic body art as well as the tattoo artists who produced it.[139]

In 2010, 25% of Australians under age 30 had tattoos.[140] Mattel released a tattooed Barbie doll in 2011, which was widely accepted, although it did attract some controversy.[141]

Author and sociology professor Beverly Yuen Thompson wrote "Covered In Ink: Tattoos, Women, and the Politics of the Body" (published in 2015, research conducted between 2007 and 2010) on the history of tattooing, and how it has been normalized for specific gender roles in the USA. She also released a documentary called "Covered", showing interviews with heavily tattooed women and female tattoo artists in the US. From the distinct history of tattooing, its historical origins and how it transferred to American culture, come transgressive styles which are put in place for tattooed men and women. These "norms" written in the social rules of tattooing imply what is considered the correct way for a gender to be tattooed.[142] Men of tattoo communities are expected to be "heavily tattooed", meaning there are many tattoos which cover multiple parts of the body, and express aggressive or masculine images, such as skulls, zombies, or dragons. Women, on the other hand, are expected to be "lightly tattooed". This means the opposite, in which there are only a small number of tattoos which are placed in areas of the body that are easy to cover up. These images are expected to be more feminine or cute (ex. Fairies, flowers, hearts). When women step outside of the "lightly tattooed" concept by choosing tattoos of a masculine design, and on parts of the body which are not easy to cover (forearms, legs), it's common to face certain types of discrimination from the public.[143] Women who are heavily tattooed can report to being stared at in public, being denied certain employment opportunities, face judgement from members of family, and may even receive sexist or homophobic slurs by strangers.

Over the past three decades Western tattooing has become a practice that has crossed social boundaries from "low" to "high" class along with reshaping the power dynamics regarding gender. It has its roots in "exotic" tribal practices of the Native Americans and Japanese, which are still seen in present times.

As various kinds of social movements progressed bodily inscription crossed class boundaries, and became common among the general public. Specifically, the tattoo is one access point for revolutionary aesthetics of women. Feminist theory has much to say on the subject. "Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo", by Margot Mifflin, became the first history of women's tattoo art when it was released in 1997. In it, she documents women's involvement in tattooing coinciding to feminist successes, with surges in the 1880s, 1920s and the 1970s.[138] Today, women sometimes use tattoos as forms of bodily reclamation after traumatic experiences like abuse or breast cancer.[138] In 2012, tattooed women outnumbered men for the first time in American history – according to a Harris poll, 23% of women in America had tattoos in that year, compared to 19% of men.[144] In 2013, Miss Kansas, Theresa Vail, became the first Miss America contestant to show off tattoos during the swimsuit competition — the insignia of the U.S. Army Dental Corps on her left shoulder and one of the "Serenity Prayer" along the right side of her torso.[145]

The legal status of tattoos is still developing. In recent years, various lawsuits have arisen in the United States regarding the status of tattoos as a copyrightable art form. However, these cases have either been settled out of court or are currently being disputed, and therefore no legal precedent exists directly on point.[146] The process of tattooing was held to be a purely expressive activity protected by the First Amendment by the Ninth Circuit in 2010.[147]

Tattoos are valuable identification marks because they tend to be permanent. They can be removed, but they do not fade, The color may, however, change with exposure to the sun. They have recently been very useful in identifying people, such as in the case of a decedent.[148] In today's industrialized cultures, tattoos and piercing are a popular art form shared by many. They are also often perceived to be indicative of defiance, independence, and belonging, such as in prison or gang cultures.[149]

Military's role in tattoos in America

Military and warfare have had a direct impact on the purpose, subject matter, and reception of tattoos in American popular culture.[150] The first recorded tattoo artist in the United States was Martin Hildebrandt, who in 1846 was tattooing sailors and soldiers with proud patriotic tattoos of flags and battles.[150] While this helped push tattooing into a popular light, simultaneously "Tattooed Freaks", like P.T. Barnum's "Prince Constantine", were inadvertently counteracting this, and keeping the world of Tattooing out of everyday life.[150] It wasn't until the invention of the Electric Tattoo Machine in the 1880s by Samuel O'Reilly that Tattooing became a little socially acceptable.[150] Still, O'Reilly reported in the 1880s that most of his clients were sailors.[150] A 1908 Article in American Anthropologist reported that 75% of sailors in the U.S. Navy were tattooed.[150] These findings led to one of the first U.S. military regulations on Tattoos in 1909, which concerned the subject matter of the tattoos allowed to be pictured on servicemen.[150]

World Wars

As World War I ravaged the globe, it also ravaged the popularity of tattooing, pushing tattoos even farther under the umbrella of delinquency.[150] What credence tattoos got as symbols of patriotism and war badges in the eyes of the public, was demolished as servicemen moved away from the proud flags motifs and into more sordid depictions.[151][150]

At the beginning of the second World War Tattooing once again experienced a boom in popularity as now not only sailors in the Navy, but soldiers in the Army and fliers in the Air Force, were once again tattooing their national pride onto their bodies.[150] Famous tattoo artist, Charles Wagner said "Funny Thing about War, fighting men just want to be marked in some way or another" as a way of reasoning for its resurgence in popularity.[150] The hype was short lived, as the craft of tattooing received a major backlash at the end of the second world war, as stories from survivors abroad made it back to the states.[150] During the Second World War, the Nazis, under the order of Adolf Hitler, rounded up those deemed inferior, into concentration camps.[152] Once there, if they were chosen to live, they were tattooed with numbers onto their arms.[152] Tattoos and Nazism become intertwined, and the extreme distaste for Nazi Germany and Fascism, led to a stronger public outcry against tattooing.[150]

Post World Wars

This backlash would further worsen with use of a tattooed man in a 1950s Marlboro advertisement, which strengthened the publics view that Tattoos were no longer for patriotic servicemen, but for criminals and degenerates.[150] The public distaste was so strong by this point, that usual trend of seeing tattoo popularity spike during times of war, was not seen in the Vietnam War.[150] It would take two more decades, and creators like Lyle Tuttle and Ed Hardy in 1970, Freddy Negrete and Jack Rudy in 1980, and celebrity patrons like Janis Joplin, Peter Fonda, and Cher, for tattooing to finally be brought back into society's good graces.[150]

Modern times/2000s

Starting in the early 2000s, tattoos and the military began to reconnect, as tattoos became a symbolic and popular way to show social and political views[153] Tattoos were being used by soldiers to show belonging, affiliation, and to mark down their war experiences.[153] Rites of passage in the military were marked with tattoos, like when one completes basic training or returns home from service.[150] Modern military tattoos in the United States became less about valor and honor, but about recognizing the experiences, losses, and struggles of servicemen.[153] Tattoos can now be seen and perceived as ways to convey loss and grief, guilt and anger, as ways to highlight the transformational nature of war on individuals, and even convey a hope for a better nation and self.[153]

The history of Tattooing in the U.S. can be seen to have been influenced and affected by war and the Military.[153][150] Though its expression and reception by the public are constantly in flux, both practices are deeply connected and still effect one another today.[153] Dyvik writes in her article, War Ink: Sense Making and Curating War Through Military Tattoos, that "war lingers in and on the bodies and lifeworlds of those who have practiced it"[153]

Global military regulations on tattoos

Throughout the world's different military branches, tattoos are either regulated under policies or strictly prohibited to fit dress code rules.

Royal Navy

As of 2022, the Royal Navy permits most tattoos, with certain restrictions: unless visible in a front-facing passport photo, obscene or offensive, or otherwise deemed inappropriate.[154]

The National Museum of the Royal Navy has presented an exhibit about the long history of tattoos among Navy service members, part of the tradition of sailor tattoos.[155]

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force regulates all kinds of body modification. Any tattoos which are deemed to be "prejudicial to good order and discipline", or "of a nature that may bring discredit upon the Air Force" are prohibited. Specifically, any tattoo which may be construed as "obscene or advocate sexual, racial, ethnic or religious discrimination" is disallowed. Tattoo removal may not be enough to qualify; resultant "excessive scarring" may be disqualifying. Further, Air Force members may not have tattoos on their neck, face, head, tongue, lips or scalp.[156]

United States Army

The United States Army regulates tattoos under AR 670–1, last updated in 2022. Soldiers are permitted to have tattoos as long as they are not on the neck, hands, or face, with exceptions existing for of one ring tattoo on each hand, a tattoo on each hand, not exceeding one inch diameter, one tattoo behind the ear, not to exceed one inch in diameter, and permanent makeup. Additionally, tattoos that are deemed to be sexist, racist, derogatory, or extremist continue to be banned.[157]

United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard policy has changes over the years. Tattoos should not be visible over the collarbone or when wearing a V-neck shirt. Tattoos or military brands on the arms should not surpass the wrist. But only one hand tattoos of a form of ring are permitted when not exceeding 0.25 in (6.4 mm) width. Face tattoos are also permitted as permanent eyeliners for females as long as they are appropriately worn and not brightly colored to fit uniform dressing code. Disrespectful derogatory tattoos and sexually explicit tattoos are prohibited on the body.[158]

United States Marine Corps

In 2016, the United States Marine Corps disclosed a new policy of standards of appearance, substituting any previous policy from the past.[159]

The policy unauthorized tattoos in different parts of the body such as the wrist, knee, elbow and above the collar bone. Wrist tattoos should be two inches above the wrist, elbow tattoos two inches above and one inch below, and the knee two inches above and two below.[159]

United States Navy

The United States Navy has changed its policies and become more lenient in its policies on tattoos, allowing neck tattoos as long as one inch. Sailors are also allowed to have as many tattoos of any size on the arms and legs, as long as they are not deemed to be offensive tattoos.[160]

India

The Indian Army tattoo policy has been in place since 11 May 2015. The government declared all tribal communities who enlist and have tattoos are allowed to have them all over the body only if they belong to a tribal community. Indians who are not part of a tribal community are only allowed to have tattoos in designated parts of the body such as the forearm, elbow, wrist, the side of the palm, and back and front of hands. Offensive, sexist and racist tattoos are not allowed.[161]

References

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron (2013). "The Material Culture and Middle Stone Age Origins of Ancient Tattooing". Tattoos and Body Modifications in Antiquity: Proceedings of the sessions at the EAA annual meetings in The Hague and Oslo, 2010/11. Zurich Studies in Archaeology. Vol. 9. Chronos Verlag. pp. 15–26.

- Krutak, Lars F.; Deter-Wolf, Aaron (2017). Ancient ink : the archaeology of tattooing. Krutak, Lars F.,, Deter-Wolf, Aaron, 1976–. Seattle. ISBN 9780295742823. OCLC 1006520865.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Robitaille, Benoît; Krutak, Lars; Galliot, Sébastien (February 2016). "The World's Oldest Tattoos" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 5: 19–24. Bibcode:2016JArSR...5...19D. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007. S2CID 162580662.

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron (11 November 2015), It's official: Ötzi the Iceman has the oldest tattoos in the world, RedOrbit.com, retrieved 15 November 2015

- Scallan, Marilyn (9 December 2015). "Ancient Ink: Iceman Otzi Has World's Oldest Tattoos". Smithsonian Science News. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Ghosh, Pallab (1 March 2018). "'Oldest tattoo' found on 5,000-year-old Egyptian mummies". BBC. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Benoît Robitaille (2007). A Preliminary Typology of Perpendicularly Hafted Bone Tipped Tattooing Instruments: Toward a Technological History of Oceanic Tattooing in Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies.Editors: Christian Gates St-Pierre and Renee Walker. Archaeopress. pp. 159–174.

- Patrick Vinton Kirch (2012). A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i. University of California Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780520273306.

- Furey, Louise (2017). "Archeological Evidence for Tattooing in Polynesia and Micronesia". In Lars Krutak & Aaron Deter-Wolf (ed.). Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing. University of Washington Press. pp. 159–184. ISBN 9780295742847.

- Julian Baldick (2013). Ancient Religions of the Austronesian World: From Australasia to Taiwan. I.B.Tauris. p. 3. ISBN 9781780763668.

- Thompson, Beverly Yuen (2015). ""I Want to Be Covered": Heavily Tattooed Women Challenge the Dominant Beauty Culture" (PDF). Covered in Ink: Tattoos, Women and the Politics of the Body. New York University Press. pp. 35–64. ISBN 9780814789209.

- "Maori Tattoo". Maori.com. Maori Tourism Limited. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Lars Krutak (2005). "The Forgotten Code: Tribal Tattoos of Papua New Guinea". Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Lars Krutak (2008). "Tattooing Among Japan's Ainu People". Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- lars Krutak (2010). "Tattoos of Indochina: Supernatural Mysteries of the Flesh". Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Sarah Corbett (6 February 2016). "Facial Tattooing of Berber Women". Ethnic Jewels Magazine. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Ozongwu, Melinda. "Tribal Marks – The 'African Tattoo'". This Is Africa. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Evans, Susan, Toby. 2013. Ancient Mexico and Central America: Archaeology and Culture History. 3rd Edition.

- Lars Krutak (2010). "Marks of Transformation: Tribal Tattooing in California and the American Southwest". Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Lars Krutak (2005). "America's Tattooed Indian Kings". Vanishing Tattoo. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Gillian Carr (2005). "Woad, tattoing, and identity in later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 24 (3): 273–292. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x.

- Diaz-Granados, Carol; Deter-Wolf, Aaron (2013). "Introduction". In Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Diaz-Granados, Carol (eds.). Drawing with Great Needles. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. xi–xv.

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron (2013). "Needle in a Haystack". In Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Diaz-Granados, Carol (eds.). Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 43–72.

- Smith, George S.; Zimmerman, Michael R. (October 1975). "Tattooing Found on a 1600 Year Old Frozen, Mummified Body from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska". American Antiquity. 40 (4): 433–437. doi:10.2307/279329. JSTOR 279329. S2CID 162379206.

- Wallace, Antoinette B. (2013). "Native American Tattooing in the Protohistoric Southeast". In Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Diaz-Granados, Carol (eds.). Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 1–42. ISBN 9780292749139. OCLC 859154939.

- Harriot, Thomas (1590). A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. Introduction by Paul Hulton (Theodore De Bry ed.). New York: Dover Publications (published 1972).

- Sagard, Gabriel (1632). Wong, George M. (ed.). The Long Journey to the Country of the Hurons. The Publications of the Champlain Society. Vol. 25. Translated by Langton, H. H. Toronto: The Champlain Society (published 1939).

- "home". puffin.creighton.edu. 11 August 2014.

- Lafitau, Joseph François (1724). Customs of the American Indians Compared with the Customs of Primitive Times. The Publications of the Champlain Society 49. Vol. 2. Reprinted, translated, and edited by William N. Fenton and Elizabeth L. Moore. Toronto: The Champlain Society (published 1977).

- Arnaquq-Baril, Alethea (2011). "Tunniit: Retracing the Lines of Inuit Tattoos". Cinema Politica. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ChristianGates St-Pierre (2018). "Needles and bodies: A microwear analysis of experimental bone tattooing instruments". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 20: 881–887. Bibcode:2018JArSR..20..881G. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.10.027.

- Aaron Deter-Wolf; et al. (2021). "Ancient Native American bone tattooing tools and pigments: Evidence from central Tennessee". Vol. 37, no. 21. ScienceDirect. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103002.

- Oosten, Jarich; Laugrand, Frédéric (January 2016). "The Bringer of Light: The Raven in Inuit Tradition". Polar Record. 42 (222): 187–204. doi:10.1017/S0032247406005341. S2CID 131055453.

- Johnston, Angela Hovak (2017). Reawakening Our Ancestors' Lines: Revitalizing Inuit Traditional Tattooing. Canada: Inhabit Media.

- Dye, David H. (2013). "Snaring Life from the Star and the Sun". In Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Diaz-Granados, Carol (eds.). Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 215–251.

- Krutak, Lars (2013). "Tattoos, Totem Marks, and War Clubs". In Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Diaz-Granados, Carol (eds.). Drawing with Great Needles: Ancient Tattoo Traditions of North America. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 95–130.

- "The Encyclopedia of World Cultures CD-ROM". Macmillan. 1998. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Gilbert, Steve (2000). Tattoo history: A source book (Paperback). New York, NY: Juno Books. ISBN 978-1-890451-06-6. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "A history of Japanese tattooing". vanishingtattoo.com. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- "紋面". 臺灣原住民族歷史語言文化大辭典.

- Blust, Robert (1995). "The prehistory of the Austronesian speaking peoples: a view from language". Journal of World Prehistory. 9 (4): 453–510. doi:10.1007/bf02221119. S2CID 153571840.