Micronesians

The Micronesians or Micronesian peoples are various closely related ethnic groups native to Micronesia, a region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They are a part of the Austronesian ethnolinguistic group, which has an Urheimat in Taiwan.[2]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 450,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Micronesian languages, Yapese, Chamorro, Palauan, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (93.1%)[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Polynesians, Melanesians, Euronesians, Austronesian peoples |

Ethno-linguistic groups classified as Micronesian include the Carolinians (Northern Mariana Islands), Chamorros (Guam & Northern Mariana Islands), Chuukese, Mortlockese, Namonuito, Paafang, Puluwat and Pollapese (Chuuk), I-Kiribati (Kiribati), Kosraeans (Kosrae), Marshallese (Marshall Islands), Nauruans (Nauru), Palauan, Sonsorolese, and Hatohobei (Palau), Pohnpeians, Pingelapese, Ngatikese, Mwokilese (Pohnpei), and Yapese, Ulithian, Woleian, Satawalese (Yap).[3][4]

Origins

Based on the current scientific consensus, the Micronesians are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, to be a subset of the sea-migrating Austronesian people, who include the Polynesians and the Melanesians. Austronesians were the first people to invent oceangoing sailing technologies (notably double-hulled sailing canoes, outrigger boats, lashed-lug boat building, and the crab claw sail), which enabled their rapid dispersal into the islands of the Indo-Pacific.[2][6][7] From 2000 BCE the Austronesians assimilated (or were assimilated by) the earlier populations on the islands in their migration pathway.[8][9][10][11][12] This intermingling occurred in the northern coast of New Guinea and adjacent islands, which was the location where the Oceanic language family developed around four thousand years or so ago, after the Austronesian languages of this area grew distinct and became a separate branch of the Austronesian family.[13]

Migrants entered Micronesia from the east and the west. Migrants from the west came from the Philippines and Indonesia, and settled the Marianas around 3500 years ago, after which Palau was settled around 3000 years ago.[13]

Migrants from the east came from eastern Melanesia and settled the Gilbert Islands, Marshall Islands, eastern and central Caroline Islands, Sonsorol, Pulo Anna, Merir and Tobi.[14][13] The migrants from the east belonged to the Lapita culture and settled eastern Micronesia over the course of several hundreds of years from perhaps the Santa Cruz Islands, around 500-100 BC. In the following centuries, the Oceanic language variant brought by the Lapita migrants diverged and became the Micronesian branch of the Oceanic languages.[13] John Lynch tentatively proposes a relationship between the Micronesian languages and the Loyalty Islands languages of Melanesia, but with the caveat "that this is something that could well be further investigated, even if only to confirm that Micronesian languages did not originate in the Loyalties."[15]

Yap was settled separately approximately 2000 years ago, as its language was brought by an Oceanic-speaking source in Melanesia,[16] perhaps the Admiralty Islands.[13]

Archeological evidence has revealed that some of the Bonin Islands were prehistorically inhabited by members of an unknown Micronesian ethnicity.[17]

List of ethnic groups

The Micronesian peoples can be divided into two cultural groups, the high-islanders and the low-islanders. The Palauans, Chamorros, Yapese, Chuukese, Pohnpeians, Kosraeans and Nauruans belong to the high-islander group. The inhabitants of the low islands (atolls) are the Marshallese and the Kiribati, whose culture is distinct from the high-islanders.[18] Low-islanders had better navigation and canoe technology, as a means of survival. High-islanders had access to reliable and abundant resources and did not need to travel much outside of their islands. High islands also possessed larger populations.[14]

Banaban people

.JPG.webp)

Raobeia Ken Sigrah claims that Banabans, native to Banaba, are ethnically distinct from other I-Kiribati.[19] The Banabans were assimilated through forced migrations and the heavy impact of the discovery of phosphate in 1900.[20] After 1945, the British authorities relocated most of the population to Rabi Island, Fiji, with subsequent waves of emigration in 1977, and from 1981 to 1983. Some Banabans subsequently returned, following the end of mining in 1979; approximately 300 were living on the island in 2001. The population of Banaba in the 2010 census was 295.[21] There is an estimated 6,000 people of Banaban descent in Fiji and other countries.[22][23]

The Banabans spoke the Banaban language, which has gone extinct due to a shift to the Gilbertese language, introduced by Christian missionaries that translated the Bible into Gilbertese and encouraged the Banabans to read it. Today, only a few words remain of the original Banaban language.[19] Today, the Banabans speak the Banaban dialect of Gilbertese, which includes words from the old Banaban language.[24]

Refaluwasch people

Refaluwasch people are a Micronesian ethnic group who originated in Oceania, in the Caroline Islands, with a total population of over 8,500 people in northern Mariana. They are also known as Remathau in the Yap's outer islands. The Carolinian word means "People of the Deep Sea." It is thought that their ancestors may have originally immigrated from Asia, Indonesia, Melanesia and to Micronesia around 2,000 years ago. Their primary language is Carolinian, called Refaluwasch by native speakers, which has a total of about 5,700 speakers. The Refaluwasch have a matriarchal society in which respect is a very important factor in their daily lives, especially toward the matriarchs. Most Refaluwasch are of the Roman Catholic faith.

The immigration of Refaluwasch to Saipan began in the early 19th century, after the Spanish reduced the local population of Chamorro natives to just 3,700. They began to immigrate mostly sailing from small canoes from other islands, which a typhoon previously devastated. The Refaluwasch have a much darker complexion than the native Chamorros.

Chamorro people

The Chamorro people are the indigenous peoples of the Mariana Islands, which are politically divided between the United States territory of Guam and the United States Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in Micronesia. The Chamorro are commonly believed to have come from Southeast Asia at around 2000 BC. They are most closely related to other Austronesian natives to the west in the Philippines and Taiwan, as well as the Carolines to the south.

The Chamorro language is included in the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup of the Austronesian family. Because Guam was colonized by Spain for over 300 years, many words derive from the Spanish language. The traditional Chamorro number system was replaced by Spanish numbers.[25]

Chuukese people

.jpg.webp)

The Chuukese people are an ethnic group of Chuuk State. They constitute 48% of the population of the Federated States of Micronesia. Their language is Chuukese. The home atoll of Chuuk is also known by the former name "Truk".

In Chuukese culture, the men were expected to defend and protect their family. They were very protective of their clan, lineage identity and property. Backing down from a fight is not seen as manly.[26]

Kiribati people

The Kiribati people, also known as I-Kiribati, Tungaru or Gilbertese, are the indigenous people of Kiribati. They speak the Gilbertese language. They number 103,000 as of 2008.[27]

Kosraean people

The Kosraeans or Kusaieans are the indigenous people of Kosrae. They speak the Kosraean language. They number around 8400 as of 2013.[28]

Marshallese people

_P.282.png.webp)

The Marshallese people (Marshallese: kajoor ri-Ṃajeḷ , laḷ ri-Ṃajeḷ) are the indigenous inhabitants of the Marshall Islands. They numbered 70,000 as of 2013.[29] Marshallese society was organized into three social classes, the iroji was the chief or landowner that headed several clans, the alap managed the clan and the rijerbal (worker) were commoners that worked the land. The three social classes treated each other well and with mutual respect.[26]

Nauruan people

The Nauruans are an ethnicity inhabiting the Pacific island of Nauru. They are most likely a blend of other Pacific peoples.[30]

The origin of the Nauruan people has not yet been finally determined. It can possibly be explained by the last Malayo-Pacific human migration (c. 1200). It was probably seafaring or shipwrecked Polynesians or Melanesians that established themselves in Nauru because there was not already an indigenous people present, whereas the Micronesians were already crossed with the Melanesians in this area.

Palauan people

The Palauans or Belauans (Palauan: Belau, ngukokl a Belau) — are the indigenous people of Palau. They numbered around 26,600 as of 2013.[31][32] Palauans are not noted for being great long-distance voyagers and navigators when compared to other Micronesian peoples. The taro is the center of their farming practices, although breadfruit has a symbolic importance.[13]

Pohnpeian people

The Pohnpeians or Ponapeans are the indigenous people of Pohnpei. They number around 28,000. They speak the Pohnpeian language.

Pohnpeian historic society was highly structured into five tribes, various clans and sub-clans; each tribe headed by two principal chiefs. The tribes were organized on a feudal basis. In theory, "all land belonged to the chiefs, who received regular tribute and whose rule was absolute." Punishments administered by chiefs included death and banishment. Tribal wars included looting, destruction of houses and canoes and killing of prisoners.[33]

Sonsorolese people

The Sonsorolese are Micronesian people, that inhabit the islands of Pulo Anna, Merir and Sonsorol in the island nation of Palau. A small proportion live in both the Northern Mariana Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia. The Sonsorolese are linguistically related to the Tobians. Most Sonsorolese live in the village of Echang near Koror, where they moved for economic reasons.[34]

The Sonsorolese are both linguistically and culturally most closely related to Carolinians. Ethnographic information about them was left by Jose Somera, a member of the Don Francisco Padilla expedition who discovered the islands in 1710. According to him, their clothing consisted of an apron, cloak and conical hat, and was similar to that described by Paul Klein in 1696 among the Carolinians.[35]

Tobian people

Tobian is a Micronesian language spoken in the Hatohobei (Tobi) and Koror states in Palau by about 150 people. In particular it is spoken on the island of Tobi (Torovei) in Hatohobei State, and also on Koro Island in Koror State.

Tobian is also known as Hatohobei or Tobi. It is closely related to Sonsorolese.

The Tobians share a cultural heritage that shows close ties with peoples of the central Caroline Islands, more than 1000 km to the northeast and on the other side of Palau.[36]

Yapese people

The Yapese people are a Micronesian ethnic group that number around 15,000. They are native to the main island of Yap and speak the Yapese language.

Languages

Fifteen distinct languages are spoken by the Micronesians.[26] The largest group of languages spoken by the Micronesians are the Micronesian languages. They belong to the family of Oceanic languages, part of the Austronesian language group. They descended from the Proto-Oceanic language, which in turn descended via Proto-Malayo-Polynesian from Proto-Austronesian. The languages in the Micronesian family are Marshallese, Gilbertese, Kosraean, Nauruan, as well as a large sub-family called the Chuukic–Pohnpeic languages containing 11 languages. The Yapese language is a separate branch of the Oceanic languages, outside of the Micronesian branch.[14]

Two Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken that do not belong to the Oceanic languages: Chamorro in the Mariana Islands and Palauan in Palau.[14]

Micronesian navigation

Micronesian navigation techniques are those navigation skills used for thousands of years by the navigators who voyaged between the islands of Micronesia in the open Pacific Ocean. These voyagers used wayfinding techniques such as the navigation by the stars, and observations of birds, ocean swells, and wind patterns, and relied on a large body of knowledge from oral tradition.[37][38][39] Weriyeng[40] is one of the last two schools of traditional navigation found in the central Caroline Islands in Micronesia, the other being Fanur.[41]

Culture

Micronesian culture is very diverse across island atolls[42] and influenced by the surrounding cultures. In the east one finds a more Polynesian culture with social classes (nobility, commoners and slaves) and in the west a more Melanesian-Indonesian influenced culture led by tribal chiefs without nobility, with the Marianas being an exception. The Micronesians form a cultural region, as they have much more in common with each other in cultural practices and social organization than with other neighboring societies in the Philippines, Indonesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.[13]

The Micronesian cultures evolved from a common foundation and share a common dominator in the relationship and dependence they have with their ancestral lands. The ancestral land influenced the social organization, family structures, the economy, shared food and common work. The Micronesian family is formed from four equally important components, the household, the nuclear family, the extended family, and a lineage. The family and the community would cooperate with fishing, farming, raising children and passing knowledge to the next generations. Individuals and families would conform their behavior to cooperate with the community.[26]

Authority was based on age, and Micronesians were taught to respect and hold their elders in high regard, which they would express by being silent in the presence of their elders. The elders would mediate and resolve conflicts.[26]

Music and dance

Most Micronesian peoples lacked musical instruments, and thus produced music only by song and chants. Important men would have songs composed about their abilities or deeds, by wives or partners. These songs could live on even after death and give the men a heroic status.[14]

Religion

The traditional religions of Micronesia were extremely heterogeneous. However, very little is known about most of them, as the islands were evangelized very early (from the 16th to 18th centuries) so that the indigenous religions could only survive on a few islands. However, some important manifestations of religious practice and thought can be identified for the entire Micronesian cultural space:[43]

- Similar creation myths (origin of people from mythical ancestors - mostly ancestral mothers)

- Culture heroes (mythical seafarers as bearers of important cultural goods)

- Mythical worldviews (land and sea areas in different "layers" and cardinal points)

- Dualistic concepts (every material thing and every living being has a spiritual double)

- Free souls, which can leave the body in a dream

- Mana (transcendent power that can be transferred to people, but also to natural phenomena, through performance and deeds, among other things)

- Religiously motivated art styles (carvings on traditional meeting houses and religious facilities)

The traditional Micronesian religions emphasized ancestor worship and embraced spirits and ghosts. After death, one's spirit would either pass on to an afterworld or stay on the island to either help or harm the living. A natural death would produce a benevolent ghost while an unnatural death would produce a malovent ghost. Other spirits were associated with places, natural objects, special crafts and activities. Various professions would make chants and offerings to their patron spirits, which they believed would control the outcome of their efforts. Micronesians believed that all sickness was caused by spirits. Shamans, mediums, diviners and sorcerers could be consulted to deal with the spirit world. Taboos would often be placed on food and sexual activities before a person would engage in an important pursuit. Violating this taboo would cause a spirit to send sickness or death to the offender or even the entire community.[14]

Mythology

Micronesian mythology comprises the traditional belief systems of the Micronesians. There is no single belief system in the islands of Micronesia, as each island region has its own mythological beings.

Traditional beliefs declined and changed with the arrival of Europeans, which occurred increasingly after the 1520s. In addition, the contact with European cultures led to changes in local myths and legends.

Gallery

A Marshallese house, 1821.

A Marshallese house, 1821. A Nauruan warrior, 1880.

A Nauruan warrior, 1880. Kiribati children

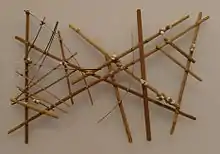

Kiribati children Presentation of Yapese stone money

Presentation of Yapese stone money Badrulchau stone monoliths

Badrulchau stone monoliths A building of Nan Madol

A building of Nan Madol

See also

References

- Center for the Study of Global Christianity (June 2013), Christianity in its Global Context, 1970–2020: Society, Religion, and Mission (PDF), South Hamilton, Massachusetts, USA: Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2013

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Mason, Leonard (1989). "A MARSHALLESE NATION EMERGES FROM THE POLITICAL FRAGMENTATION OF AMERICAN MICRONESIA". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.455.1089.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Hawaii Health Data Warehouse Race-Ethnicity Documentation" (PDF). August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Chambers, Geoff (15 January 2013). "Genetics and the Origins of the Polynesians". eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020808.pub2. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- Dierking, Gary (2007). Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes: Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats. International Marine/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071594561.

- Horridge, Adrian (1986). "The Evolution of Pacific Canoe Rigs". The Journal of Pacific History. 21 (2): 83–89. doi:10.1080/00223348608572530. JSTOR 25168892.

- Bellwood, Peter (1988). "A Hypothesis for Austronesian Origins" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 26 (1): 107–117. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Bellwood, Peter (1991). "The Austronesian Dispersal and the Origin of Languages". Scientific American. 265 (1): 88–93. Bibcode:1991SciAm.265a..88B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0791-88. JSTOR 24936983.

- Hill, Adrian V.S.; Serjeantson, Susan W., eds. (1989). The Colonization of the Pacific: A Genetic Trail. Research Monographs on Human Population Biology No. 7. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198576952.

- Bellwood P, Fox JJ, Tryon D (2006). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Australian National University Press. ISBN 9781920942854. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Blench, Roger (2012). "Almost Everything You Believed about the Austronesians Isn't True" (PDF). In Tjoa-Bonatz, Mai Lin; Reinecke, Andreas; Bonatz, Dominik (eds.). Crossing Borders. National University of Singapore Press. pp. 128–148. ISBN 9789971696429. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Petersen, Glenn (2009). Traditional Micronesian Societies Adaptation, Integration, and Political Organization in the Central Pacific.

- Alkire, William H (1977). An introduction to the peoples and cultures of Micronesia.

- Lynch, John (2003). "The Bilabials in Proto Loyalties". In Lynch, John (ed.). Issues in Austronesian Historical Phonology. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 153-173 (171). doi:10.15144/PL-550.153.

- Carson, Mike T. (2013). "Austronesian Migrations and Developments in Micronesia".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "小笠原諸島の歴史". www.iwojima.jp.

- "High-island and low-island cultures". Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- Sigrah, Raobeia Ken, and Stacey M. King (2001). Te rii ni Banaba.. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. ISBN 982-02-0322-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Banaba: The island Australia ate". Radio National. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "19. Banaba" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitenti – Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Teaiwa, Katerina Martina (2014). Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from Banaba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253014528.

- Prestt, Kate (2017). "Australia's shameful chapter". 49(1) ANUReporter. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Kiribati

- Rodríguez-Ponga Salamanca, Rafael (2009). Del español al chamorro: Lenguas en contacto en el Pacífico [From Spanish to Chamorro: languages in contact in the Pacific] (in Spanish). Madrid: Ediciones Gondo. ISBN 978-84-933774-4-1. OCLC 436267171.

- Palafox, Neal; Riklon, Sheldon; Esah, Sekap; Rehuher, Davis; Swain, William; Stege, Kristina; Naholowaa, Dale; Hixon, Allen; Ruben, Kino (1980). "People and Cultures of Hawaii". University of Hawaii Press. 15. The Micronesians. doi:10.1515/9780824860264-018. S2CID 239441571.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Kiribertese | Joshua Project". www.joshuaproject.net.

- "Kosraen | Joshua Project". www.joshuaproject.net.

- "Marshallese | Joshua Project".

- Bay-Hansen, C.D. (2006). FutureFish 2001: FutureFish in Century 21: The North Pacific Fisheries Tackle Asian Markets, the Can-Am Salmon Treaty, and Micronesian Seas. Trafford Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 1-55369-293-4.

- "Palauan | Joshua Project". www.joshuaproject.net.

- Project, Joshua. "Palauan, English-speaking in Palau". joshuaproject.net.

- Riesenberg, Saul H (1968). The Native Polity of Ponape. Contributions to Anthropology. Vol. 10. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 38, 51. ISBN 9780598442437. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- "Sonsorolese language". Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- "Early European Contact with the Western Carolines". micsem.org.

- Snyder, David.; Adams, William Hampton; Butler, Brian M. (1997). Archaeology and historic preservation in Palau. Anthropology research series / Division of Cultural Affairs, Republic of Palau 2. San Francisco: U.S. National Park Service.

- Holmes, Lowell Don (1 June 1955). "Island Migrations (1): The Polynesian Navigators Followed a Unique Plan". XXV(11) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- Holmes, Lowell Don (1 August 1955). "Island Migrations (2): Birds and Sea Currents Aided Canoe Navigators". XXVI(1) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- Holmes, Lowell Don (1 September 1955). "Island Migrations (3): Navigation was an Exact Science for Leaders". XXVI(2) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- Gladwin, Thomas (1970). East Is a Big Bird. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 200. ISBN 0-674-22425-6.

- Woodward, David (1998). History of Cartography. University of Chicago Press. p. 470. ISBN 0-226-90728-7. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (2017). On the Road of the Winds: An Archeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact (2nd Rev. ed.). Oakland: University of California Press. pp. 42–45. ISBN 978-0520292819.

- Erckenbrecht, Corinna (2002). "Traditionelle Religionen". Harenberg Lexikon der Religionen. Harenberg, Dortmund. pp. 942–943. ISBN 361101060-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link).