History of the Palestinians

The Palestinian people (Arabic: الشعب الفلسطيني, ash-sha'ab il-filastini) are an Arabic-speaking people with family origins in the region of Palestine. Since 1964, they have been referred to as Palestinians (Arabic: الفلسطينيين, al-filastiniyyin), but before that they were usually referred to as Palestinian Arabs (Arabic: العربي الفلسطيني, al-'arabi il-filastini). During the period of the British Mandate, the term Palestinian was also used to describe the Jewish community living in Palestine. The Arabic-language newspaper Falastin (Palestine) was founded in 1911 by Palestinian Christians.

Ottoman occupation (1834–1917)

Nationalist feeling

Under the Ottomans, Palestine's Arab population mostly saw themselves as Ottoman subjects. Kimmerling and Migdal consider the revolt in 1834 of the Arabs in Palestine as the first formative event of the Palestinian people. In the 1830s, Palestine was occupied by the Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans, Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha. The revolt was precipitated by popular resistance against heavy demands for conscripts. Peasants were well aware that conscription was nothing less than a death sentence. Starting in May 1834, the rebels took many cities, among them Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus. In response, Ibrahim Pasha sent in his army, finally defeating the last rebels on 4 August in Hebron.[1] Nevertheless, the Arabs in Palestine remained part of a Pan-Islamist or Pan-Arab national movement.[2]

In 1882 the population numbered approximately 320,000 people, 25,000 of whom were Jewish.[3] Many of these were Arab Jews and in the narrative works of Arabs in Palestine in the late Ottoman period – as evidenced in the autobiographies and diaries of Khalil Sakakini and Wasif Jawhariyyeh – "native" Jews were often referred to as abnaa al-balad (sons of the country), 'compatriots', or Yahud awlad Arab ("Jews, sons of Arabs").[4]

At the beginning of the 20th century, a "local and specific Palestinian patriotism" emerged. The Palestinian identity grew progressively. In 1911, a newspaper named Falastin was established in Jaffa by Palestinian Christians and the first Palestinian nationalist organisations appeared at the end of the World War I[5] Two political factions emerged. al-Muntada al-Adabi, dominated by the Nashashibi family, militated for the promotion of the Arab language and culture, for the defense of Islamic values and for an independent Syria and Palestine. In Damascus, al-Nadi al-Arabi, dominated by the Husayni family, defended the same values.[6]

When the First Palestinian Congress of February 1919 issued its anti-Zionist manifesto rejecting Zionist immigration, it extended a welcome to those Jews "among us who have been Arabicized, who have been living in our province since before the war; they are as we are, and their loyalties are our own."[4]

According to Benny Morris, Palestinian Arab nationalism as a distinct movement appeared between April and July 1920,[6] after the Nebi Musa riots, the San Remo conference and the failure of Faisal to establish the Kingdom of Greater Syria.[7][8]

Zionism

When Zionism began taking root among Jewish communities in Europe, many Jews emigrated to Palestine and established settlements there. When Palestinian Arabs concerned themselves with Zionists, they generally assumed the movement would fail. After the Young Turk revolution in 1908, Arab Nationalism grew rapidly in the area and most Arab Nationalists regarded Zionism as a threat, although a minority perceived Zionism as providing a path to modernity.[9] Though there had already been Arab protests to the Ottoman authorities in the 1880s against land sales to foreign Jews, the most serious opposition began in the 1890s after the full scope of the Zionist enterprise became known. There was a general sense of threat. This sense was heightened in the early years of the 20th century by Zionist attempts to develop an economy from which Arab people were largely excluded, such as the "Hebrew labor" movement which campaigned against the employment of cheap Arab labour. The creation of the British Mandate of Palestine in 1918 and the Balfour Declaration greatly increased Arab fears.

Contemporary writing

The Outline of History, by H.G.Wells (1920), notes the following about this geographic region and the turmoil of the times:

It was clearly a source of strength to them [Turks], rather than weakness, that they were cut off altogether from their age-long ineffective conflict with the Arab. Syria, Mesopotamia, were entirely detached from Turkish rule. Palestine was made a separate state within the British sphere, earmarked as a national home for the Jews. A flood of poor Jewish immigrants poured into the promised land and was speedily involved in serious conflicts with the Arab population. The Arabs had been consolidated against the Turks and inspired with a conception of national unity through the exertions of a young Oxford scholar, Colonel Lawrence. His dream of an Arab kingdom with its capital at Damascus was speedily shattered by the hunger of the French and British for mandatory territory, and in the end his Arab kingdom shrank to the desert kingdom of the Hedjaz and various other small and insecure imamates, emirates and sultanates. If ever they are united, and struggle into civilization, it will not be under Western auspices.[10]

Arab Revolt and conquest of Palestine by the British army

British Mandate (1920–1947)

Palestinian Arabs' political rights

The Palestinian Arabs felt ignored by the terms of the Mandate. Though at the beginning of the Mandate they constituted a 90 percent majority of the population, the text only referred to them as "non-Jewish communities" that, though having civil and religious rights, were not given any national or political rights. As far as the League of Nations and the British were concerned the Palestinian Arabs were not a distinct people. In contrast the text included six articles (2, 4, 6, 7, 11 and 22) with obligations for the mandatory power to foster and support a "national home" for the Jewish people. Moreover, a representative body of the Jewish people, the Jewish Agency, was recognised.[11]

The Palestinian Arab leadership repeatedly pressed the British to grant them national and political rights like representative government, reminding the British of president Wilson's Fourteen Points, the Covenant of the League of Nations and British promises during World War I. The British however made acceptance of the terms of the Mandate a precondition for any change in the constitutional position of the Palestinian Arabs. For the Palestinian Arabs this was unacceptable, as they felt that this would be "self murder".[12] During the whole interwar period the British, appealing to the terms of the Mandate, which they had designed themselves, rejected the principle of majority rule or any other measure that would give a Palestinian Arab majority control over the government of Palestine.[13]

There was also a contrast with other Class A Mandates. By 1932 Iraq was independent, and Syria, Lebanon and Transjordan had national parliaments, Arab government officials up to the rank of minister, and substantial power in Arabs hands. In other Arab countries there were also indigenous state structures, except in some countries like Libya and Algeria, which, like Palestine, were subject to large-scale settlement programmes.[14]

Not having a recognized body of representatives was a severe handicap for the Palestinian Arabs compared to the Zionists. The Jewish Agency was entitled to diplomatic representation e.g. in Geneva before the League of Nations Permanent Mandates Commission, while the Palestinian Arabs had to be represented by the British.[15]

Development

Rashid Khalidi made a comparison between the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, and the Palestinian Arabs on the one hand, and between the Palestinian Arabs and other Arabs on the other hand. From 1922 to 1947 the annual growth rate of the Jewish sector of the economy was 13.2%, mainly due to immigration and foreign capital, while that of the Arab was 6.5%. Per capita these figures were 4.8% and 3.6% respectively. By 1936 the Jewish sector had eclipsed the Arab one, and Jewish individuals earned 2.6 times as much as Arabs.[16] Compared to other Arab countries the Palestinian Arab individuals earned slightly better.[17] In terms of human capital there was a huge difference. For instance the literacy rates in 1932 were 86% for the Jews against 22% for the Palestinian Arabs, but Arab literacy was steadily increasing. In this respect the Palestinian Arabs compared favorably to Egypt and Turkey, but unfavorably to Lebanon.[18] On the scale of the UN Human Development Index determined for around 1939, of 36 countries, Palestinian Jews were placed 15th, Palestinian Arabs 30th, Egypt 33rd and Turkey 35th.[19] The Jews in Palestine were mainly urban, 76.2% in 1942, while the Arabs were mainly rural, 68,3% in 1942.[20] Overall Khalidi concludes that the Palestinian Arab society, while being overmatched by the Yishuv, was as advanced as any other Arab society in the region and considerably more as several.[21]

Palestinian leadership

The Palestinian Arabs were led by two main camps. The Nashashibis, led by Raghib al-Nashashibi, who was Mayor of Jerusalem from 1920 to 1934, were moderates who sought dialogue with the British and the Jews. The Nashashibis were overshadowed by the al-Husaynis who came to dominate Palestinian-Arab politics in the years before 1948. The al-Husaynis, like most Arab Nationalists, denied that Jews had any national rights in Palestine.

The British granted the Palestinian Arabs a religious leadership, but they always kept it dependent.[22] The office of Mufti of Jerusalem, traditionally limited in authority and geographical scope, was refashioned into that of Grand Mufti of Palestine. Furthermore, a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC) was established and given various duties like the administration of religious endowments and the appointment of religious judges and local muftis. In Ottoman times these duties had been fulfilled by the bureaucracy in Istanbul.[22]

In ruling the Palestinian Arabs the British preferred to deal with elites, rather than with political formations rooted in the middle or lower classes.[23] For instance they ignored the Palestine Arab Congress. The British also tried to create divisions among these elites. For instance they chose Hajj Amin al-Husayni to become Grand Mufti, although he was young and had received the fewest votes from Jerusalem's Islamic leaders.[24] Hajj Amin was a distant cousin of Musa Kazim al-Husainy, the leader of the Palestine Arab Congress. According to Khalidi, by appointing a younger relative, the British hoped to undermine the position of Musa Kazim.[25] Indeed, they stayed rivals until the death of Musa Kazim in 1934. Another of the mufti's rivals, Raghib Bey al-Nashashibi, had already been appointed mayor of Jerusalem in 1920, replacing Musa Kazim whom the British removed after the Nabi Musa riots of 1920,[26][27] during which he exhorted the crowd to give their blood for Palestine.[28] During the entire Mandate period, but especially during the latter half the rivalry between the mufti and al-Nashashibi dominated Palestinian politics.

Many notables were dependent on the British for their income. In return for their support of the notables the British required them to appease the population. According to Khalidi this worked admirably well until the mid-1930s, when the mufti was pushed into serious opposition by a popular explosion.[29] After that the mufti became the deadly foe of the British and the Zionists.

According to Khalidi before the mid-1930s the notables from both the al-Husayni and the al-Nashashibi factions acted as though by simply continuing to negotiate with the British they could convince them to grant the Palestinians their political rights.[30] The Arab population considered both factions as ineffective in their national struggle, and linked to and dependent on the British administration. Khalidi ascribes the failure of the Palestinian leaders to enroll mass support to their experience during the Ottoman period, when they were part of the ruling elite and were accustomed to command. The idea of mobilising the masses was thoroughly alien to them.[31]

There had already been rioting and attacks on and massacres of Jews in 1921 and 1929. During the 1930s Palestinian Arab popular discontent with Jewish immigration and increasing Arab landlessness grew. In the late 1920s and early 1930s several factions of Palestinian society, especially from the younger generation, became impatient with the internecine divisions and ineffectiveness of the Palestinian elite and engaged in grass-roots anti-British and anti-Zionist activism organized by groups such as the Young Men's Muslim Association. There was also support for the growth in influence of the radical nationalist Independence Party (Hizb al-Istiqlal), which called for a boycott of the British in the manner of the Indian Congress Party. Some even took to the hills to fight the British and the Zionists. Most of these initiatives were contained and defeated by notables in the pay of the Mandatory Administration, particularly the mufti and his cousin Jamal al-Husayni. The younger generation also formed the backbone of the organisation of the six-month general strike of 1936, which marked the start of the great Palestinian Revolt.[32] According to Khalidi this was a grass-roots uprising, which was eventually adopted by the old Palestinian leadership, whose 'inept leadership helped to doom these movements as well'.

The Great Arab Revolt (1936–1939)

The death of the Shaykh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam at the hands of the British police near Jenin in November 1935 generated widespread outrage and huge crowds accompanied Qassam's body to his grave in Haifa. A few months later, in April 1936, an Arab national general strike broke out. This lasted until October 1936. During the summer of that year thousands of Jewish-farmed acres and orchards were destroyed, Jews were attacked and killed and some Jewish communities, such as those in Beisan and Acre, fled to safer areas.[33] After the strike, one of the longest ever anticolonial strikes, the violence abated for about a year while the British sent the Peel Commission to investigate.[32]

In 1937, the Peel Commission proposed a partition between a small Jewish state, with a proposal to transfer its Arab population to the neighboring Arab state, and an Arab state to be attached to Jordan. The proposal was rejected by the Arabs. The 2 main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and Ben-Gurion had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more negotiation.[34][35][36][37][38]

In the wake of the Peel Commission recommendation an armed uprising spread through the country. Over the next 18 months the British lost control of Jerusalem, Nablus, and Hebron. British forces, supported by 6,000 armed Jewish auxiliary police,[39] suppressed the widespread riots with overwhelming force. The British officer Charles Orde Wingate (who supported a Zionist revival for religious reasons[40]) organized Special Night Squads composed of British soldiers and Jewish volunteers such as Yigal Alon, which "scored significant successes against the Arab rebels in the lower Galilee and in the Jezreel valley"[41] by conducting raids on Arab villages. The British mobilised up to 20,000 Jews (policemen, field troops and night squads). The Jewish militias the Stern Gang and Irgun used violence also against civilians, attacking marketplaces and buses.

The Revolt resulted in the deaths of 5,000 Palestinians and the wounding of 10,000. In total 10 percent of the adult male population was killed, wounded, imprisoned, or exiled.[42] The Jewish population had 400 killed; the British 200. Significantly, from 1936 to 1945, whilst establishing collaborative security arrangements with the Jewish Agency, the British confiscated 13,200 firearms from Arabs and 521 weapons from Jews.[43]

The attacks on the Jewish population by Arabs had three lasting effects: First, they led to the formation and development of Jewish underground militias, primarily the Haganah ("The Defense"), which were to prove decisive in 1948. Secondly, it became clear that the two communities could not be reconciled, and the idea of partition was born. Thirdly, the British responded to Arab opposition with the White Paper of 1939, which severely restricted Jewish land purchase and immigration. However, with the advent of World War II, even this reduced immigration quota was not reached. The White Paper policy also radicalized segments of the Jewish population, who after the war would no longer cooperate with the British.

The revolt had a negative effect on Palestinian national leadership, social cohesion and military capabilities and contributed to the outcome of the 1948 War because "when the Palestinians faced their most fateful challenge in 1947–49, they were still suffering from the British repression of 1936–39, and were in effect without a unified leadership. Indeed, it might be argued that they were virtually without any leadership at all".[44]

Arab nationalism

Throughout the Mandatory period, some Arab residents of Palestine preferred a future as part of a broader Arab nation, usually concretized either as a nation of Greater Syria (to include what are now Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, the West Bank and Gaza) or a unified Arab state including what are now Jordan, Israel, Gaza and the West Bank.[45]

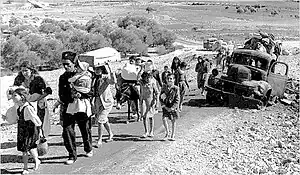

1948 Palestinian Exodus (1948–1949)

The 1948 Palestinian exodus refers to the refugee flight of Palestinian Arabs during and after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. It is referred to by most Palestinians and Arabs as the Nakba (Arabic: النكبة), meaning "disaster", "catastrophe", or "cataclysm".[46]

The United Nations (UN) final estimate of the number of Palestinian refugees outside Israel after the 1948 War was placed at 711,000 in 1951.[47] The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East defines a Palestine refugee as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948". About a quarter of the estimated 160,000 Arab Palestinians remaining in Israel were internal refugees. Today, Palestinian refugees and their descendants are estimated to number over 4 million people.

See also

- Demographic history of Palestine (region)

- Timeline of the name Palestine

- List of Palestinians

- Arab diaspora

- Palestinian people

- Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

- British Mandate of Palestine

- Palestine Liberation Organization

- Proposals for a Palestinian state

- History of Palestine

- 1948 Palestine war

- 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine

- 1948 Arab–Israeli war

- Israeli–Palestinian conflict

- 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight

Footnotes

- Kimmerling & Migdal, 2003, 'The Palestinian people', p. 6-11

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pp.40–42 in the French edition.

- Kimmerling, 2003, p. 214.

- Salim Tamari. "Ishaq al-Shami and the Predicament of the Arab Jew in Palestine" (PDF). Jerusalem Quarterly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p.48 in the French edition.

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p.49 in the French edition.

- Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pp.49–50 in the French edition.

- Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete, p.139n.

- Mohammed Muslih, The Origins of Palestinian Nationalism, New York 1988, chapter 3, See also Yehoshua Porath, The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement 1918–1929, introduction.

- H.G.Wells, 1920, Outline of History, pp. 1122–24

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 32-33.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 33, 34.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 32,36.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 38-40.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 43,44.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 13–14.

- Khalidi (2006), p. 27.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 14, 24.

- Khalidi (2006), p. 16.

- Khalidi (2006), p. 17.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 29-30.

- Khalidi (2006), p. 63.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 52.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 46-57.

- Khalidi (2006), p. 59.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 63, 69.

- Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete, 2000, ch. Nebi Musa.

- B. Morris, 1999, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist–Arab Conflict 1881–2001, p. 112

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 63, 64, 72–73, 85

- Khalidi (2006), p. 78.

- Khalidi (2006), p. 81.

- Khalidi (2006), pp. 87, 90.

- Gilbert, 1998, p. 80.

- William Roger Louis, Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization, 2006, p.391

- Benny Morris, One state, two states:resolving the Israel/Palestine conflict, 2009, p. 66

- Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, p. 48; p. 11 "while the Zionist movement, after much agonising, accepted the principle of partition and the proposals as a basis for negotiation"; p. 49 "In the end, after bitter debate, the Congress equivocally approved –by a vote of 299 to 160 – the Peel recommendations as a basis for further negotiation."

- 'Zionists Ready To Negotiate British Plan As Basis', The Times Thursday, August 12, 1937; pg. 10; Issue 47761; col B.

- Eran, Oded. "Arab-Israel Peacemaking." The Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East. Ed. Avraham Sela. New York: Continuum, 2002, page 122.

- Gilbert, 1998, p. 85. The Jewish Settlement Police were set up and equipped with trucks and armored cars by the British working with the Jewish Agency.

- van Creveld, 2004, p. 45.

- Black, 1992, p. 14.

- (see Khalidi, 2001)

- Khalidi, 1987, p. 845 (cited in Khalidi, 2001).

- R. Khalidi, 2001, p. 29.

- Army of Shadows, Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917–1948, Hillel Cohen, Translated by Haim Watzman, University of California Press, 2008, p. 264

- A History of the Modern Middle East by William L. Cleaveland, 2004, p. 270 The term "Nakba" emerged after an influential Arab commentary on the self-examination of the social and political bases of Arab life in the wake of the 1948 War by Constantine Zureiq. The term became quite popular and widespread that it made the term "disaster" synonymous with the Arab defeat in that war.

- United Nations General Assembly (1951-08-23). "General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine". Archived from the original (OpenDocument) on 2007-03-10. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

References

- Drummond, Dorothy Weitz (2004). Holy Land, Whose Land?: Modern Dilemma, Ancient Roots. Fairhurst Press. ISBN 0-9748233-2-5

- Howell, Mark (2007). What Did We Do to Deserve This? Palestinian Life under Occupation in the West Bank, Garnet Publishing. ISBN 1-85964-195-4

- Khalidi, Rashid (1997). Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10514-9. LCCN 96045757. OCLC 35637858.

- Khalidi, Rashid (2006). The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood, Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-8070-0308-5

- Kimmerling, Baruch (2003). Politicide: Ariel Sharon's War Against the Palestinians. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-517-7

- Kimmerling, Baruch & Migdal, Joel S., 2003, The Palestinian People: A History, Harvard UP, ISBN 0-674-01129-5

- Porath, Yehoshua (1974). The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement 1918–1929. London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd. ISBN 0-7146-2939-1

- Porath, Yehoshua (1977). Palestinian Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion: 1929–1939, vol. 2, London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd.