Good Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Holy and Great Friday), and Black Friday.[1][2][3]

| Good Friday | |

|---|---|

A Stabat Mater depiction, 1868 | |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | Commemoration of the crucifixion and the death of Jesus Christ |

| Celebrations | Celebration of the Passion of the Lord |

| Observances | Worship services, prayer and vigil services, fasting, almsgiving |

| Date | The Friday immediately preceding Easter Sunday |

| 2022 date |

|

| 2023 date |

|

| 2024 date |

|

| 2025 date |

|

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Passover, Christmas (which celebrates the birth of Jesus), Septuagesima, Quinquagesima, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Lent, Palm Sunday, Holy Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, and Holy Saturday which lead up to Easter, Easter Sunday (primarily), Divine Mercy Sunday, Ascension, Pentecost, Whit Monday, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi and Feast of the Sacred Heart which follow it. It is related to the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, which focuses on the benefits, graces, and merits of the Cross, rather than Jesus's death. |

Members of many Christian denominations, including the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist, Oriental Orthodox, United Protestant and some Reformed traditions (including certain Continental Reformed, Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches), observe Good Friday with fasting and church services.[4][5][6] In many Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican and Methodist churches, the Service of the Great Three Hours' Agony is held from noon until 3 pm, the time duration that the Bible records as darkness covering the land to Jesus' sacrificial death on the cross.[7] Communicants of the Moravian Church have a Good Friday tradition of cleaning gravestones in Moravian cemeteries.[8]

The date of Good Friday varies from one year to the next in both the Gregorian and Julian calendars. Eastern and Western Christianity disagree over the computation of the date of Easter and therefore of Good Friday. Good Friday is a widely instituted legal holiday around the world, including in most Western countries and 12 U.S. states.[9] Some predominantly Christian countries, such as Germany, have laws prohibiting certain acts such as dancing and horse racing, in remembrance of the somber nature of Good Friday.[10][11]

Etymology

'Good Friday' comes from the sense 'pious, holy' of the word "good".[12] Less common examples of expressions based on this obsolete sense of "good" include "the good book" for the Bible, "good tide" for "Christmas" or Shrovetide, and Good Wednesday for the Wednesday in Holy Week.[13] A common folk etymology incorrectly analyzes "Good Friday" as a corruption of "God Friday" similar to the linguistically correct description of "goodbye" as a contraction of "God be with you". In Old English, the day was called "Long Friday" (langa frigedæg [ˈlɑŋɡɑ ˈfriːjedæj]), and equivalents of this term are still used in Scandinavian languages and Finnish.[14]

Other languages

In Latin, the name used by the Catholic Church until 1955 was Feria sexta in Parasceve ("Friday of Preparation [for the Sabbath]"). In the 1955 reform of Holy Week, it was renamed Feria sexta in Passione et Morte Domini ("Friday of the Passion and Death of the Lord"), and in the new rite introduced in 1970, shortened to Feria sexta in Passione Domini ("Friday of the Passion of the Lord").

In Dutch, Good Friday is known as Goede Vrijdag, in Frisian as Goedfreed. In German-speaking countries, it is generally referred to as Karfreitag ("Mourning Friday", with Kar from Old High German kara‚ "bewail", "grieve"‚ "mourn", which is related to the English word "care" in the sense of cares and woes), but it is sometimes also called Stiller Freitag ("Silent Friday") and Hoher Freitag ("High Friday, Holy Friday"). In the Scandinavian languages and Finnish ("pitkäperjantai"), it is called the equivalent of "Long Friday" as it was in Old English ("Langa frigedæg").

In Irish it is known as Aoine an Chéasta, "Friday of Crucifixion", from céas, "suffer;"[15] similarly, it is DihAoine na Ceusta in Scottish Gaelic.[16] In Welsh it is called Dydd Gwener y Groglith, "Friday of the Cross-Reading", referring to Y Groglith, a medieval Welsh text on the Crucifixion of Jesus that was traditionally read on Good Friday.[17]

In Greek, Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, Breton and Armenian it is generally referred to as the equivalent of "Great Friday" (Μεγάλη Παρασκευή, Wielki Piątek, Nagypéntek, Vinerea Mare, Gwener ar Groaz, Ավագ Ուրբաթ). In Serbian, it is referred either Велики петак ("Great Friday"), or, more commonly, Страсни петак ("Suffer Friday"). In Bulgarian, it is called either Велики петък ("Great Friday"), or, more commonly, Разпети петък ("Crucified Friday"). In French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese it is referred to as Vendredi saint, Venerdì santo, Viernes Santo and Sexta-Feira Santa ("Holy Friday"), respectively. In Arabic and Maltese, it is known as "الجمعة العظيمة" and Il-Ġimgħa l-Kbira ("Great Friday") respectively. In Malayalam, it is called ദുഃഖ വെള്ളി ("Sad Friday").

Biblical accounts

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

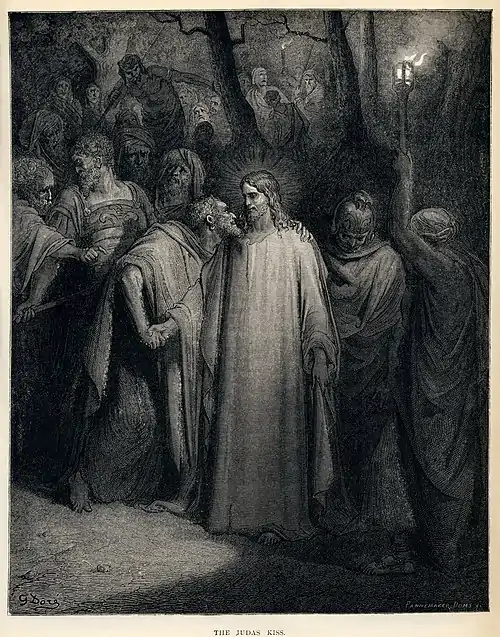

According to the accounts in the Gospels, the royal soldiers, guided by Jesus' disciple Judas Iscariot, arrested Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane. Judas received money (30 pieces of silver) [18] for betraying Jesus and told the guards that whomever he kisses is the one they are to arrest. Following his arrest, Jesus was taken to the house of Annas, the father-in-law of the high priest, Caiaphas. There he was interrogated with little result and sent bound to Caiaphas the high priest where the Sanhedrin had assembled.[19]

Conflicting testimony against Jesus was brought forth by many witnesses, to which Jesus answered nothing. Finally the high priest adjured Jesus to respond under solemn oath, saying "I adjure you, by the Living God, to tell us, are you the Anointed One, the Son of God?" Jesus testified ambiguously, "You have said it, and in time you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of the Almighty, coming on the clouds of Heaven." The high priest condemned Jesus for blasphemy, and the Sanhedrin concurred with a sentence of death.[20] Peter, waiting in the courtyard, also denied Jesus three times to bystanders while the interrogations were proceeding just as Jesus had foretold.

In the morning, the whole assembly brought Jesus to the Roman governor Pontius Pilate under charges of subverting the nation, opposing taxes to Caesar, and making himself a king.[21] Pilate authorized the Jewish leaders to judge Jesus according to their own law and execute sentencing; however, the Jewish leaders replied that they were not allowed by the Romans to carry out a sentence of death.[22]

Pilate questioned Jesus and told the assembly that there was no basis for sentencing. Upon learning that Jesus was from Galilee, Pilate referred the case to the ruler of Galilee, King Herod, who was in Jerusalem for the Passover Feast. Herod questioned Jesus but received no answer; Herod sent Jesus back to Pilate. Pilate told the assembly that neither he nor Herod found Jesus to be guilty; Pilate resolved to have Jesus whipped and released.[23] Under the guidance of the chief priests, the crowd asked for Barabbas, who had been imprisoned for committing murder during an insurrection. Pilate asked what they would have him do with Jesus, and they demanded, "Crucify him"[24] Pilate's wife had seen Jesus in a dream earlier that day, and she forewarned Pilate to "have nothing to do with this righteous man".[25] Pilate had Jesus flogged and then brought him out to the crowd to release him. The chief priests informed Pilate of a new charge, demanding Jesus be sentenced to death "because he claimed to be God's son." This possibility filled Pilate with fear, and he brought Jesus back inside the palace and demanded to know from where he came.[26]

.jpg.webp)

Coming before the crowd one last time, Pilate declared Jesus innocent and washed his own hands in water to show he had no part in this condemnation. Nevertheless, Pilate handed Jesus over to be crucified in order to forestall a riot.[27] The sentence written was "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews." Jesus carried his cross to the site of execution (assisted by Simon of Cyrene), called the "place of the Skull", or "Golgotha" in Hebrew and in Latin "Calvary". There he was crucified along with two criminals.[28]

Jesus agonized on the cross for six hours. During his last three hours on the cross, from noon to 3 pm, darkness fell over the whole land.[29] In the gospels of Mathew and Mark, Jesus is said to have spoken from the cross, quoting the messianic Psalm 22: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?"[30]

With a loud cry, Jesus gave up his spirit. There was an earthquake, tombs broke open, and the curtain in the Temple was torn from top to bottom. The centurion on guard at the site of crucifixion declared, "Truly this was God's Son!"[31]

Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin and a secret follower of Jesus, who had not consented to his condemnation, went to Pilate to request the body of Jesus[32] Another secret follower of Jesus and member of the Sanhedrin named Nicodemus brought about a hundred-pound weight mixture of spices and helped wrap the body of Jesus.[33] Pilate asked confirmation from the centurion of whether Jesus was dead.[34] A soldier pierced the side of Jesus with a lance causing blood and water to flow out[35] and the centurion informed Pilate that Jesus was dead.[36]

Joseph of Arimathea took Jesus' body, wrapped it in a clean linen shroud, and placed it in his own new tomb that had been carved in the rock[37] in a garden near the site of the crucifixion. Nicodemus[38] also brought 75 pounds of myrrh and aloes, and placed them in the linen with the body, in keeping with Jewish burial customs[33] They rolled a large rock over the entrance of the tomb.[39] Then they returned home and rested, because Shabbat had begun at sunset.[40]

Orthodox

Byzantine Christians (Eastern Christians who follow the Rite of Constantinople: Orthodox Christians and Greek-Catholics) call this day "Great and Holy Friday", or simply "Great Friday".[41] Because the sacrifice of Jesus through his crucifixion is recalled on this day, the Divine Liturgy (the sacrifice of bread and wine) is never celebrated on Great Friday, except when this day coincides with the Great Feast of the Annunciation, which falls on the fixed date of 25 March (for those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, 25 March currently falls on 7 April of the modern Gregorian Calendar). Also on Great Friday, the clergy no longer wear the purple or red that is customary throughout Great Lent,[42] but instead don black vestments. There is no "stripping of the altar" on Holy and Great Thursday as in the West; instead, all of the church hangings are changed to black, and will remain so until the Divine Liturgy on Great Saturday.

The faithful revisit the events of the day through the public reading of specific Psalms and the Gospels, and singing hymns about Christ's death. Rich visual imagery and symbolism, as well as stirring hymnody, are remarkable elements of these observances. In the Orthodox understanding, the events of Holy Week are not simply an annual commemoration of past events, but the faithful actually participate in the death and the resurrection of Jesus.

Each hour of this day is the new suffering and the new effort of the expiatory suffering of the Savior. And the echo of this suffering is already heard in every word of our worship service – unique and incomparable both in the power of tenderness and feeling and in the depth of the boundless compassion for the suffering of the Savior. The Holy Church opens before the eyes of believers a full picture of the redeeming suffering of the Lord beginning with the bloody sweat in the Garden of Gethsemane up to the crucifixion on Golgotha. Taking us back through the past centuries in thought, the Holy Church brings us to the foot of the cross of Christ erected on Golgotha and makes us present among the quivering spectators of all the torture of the Savior.[43]

Great and Holy Friday is observed as a strict fast, also called the Black Fast, and adult Byzantine Christians are expected to abstain from all food and drink the entire day to the extent that their health permits. "On this Holy day neither a meal is offered nor do we eat on this day of the crucifixion. If someone is unable or has become very old [or is] unable to fast, he may be given bread and water after sunset. In this way we come to the holy commandment of the Holy Apostles not to eat on Great Friday."[43]

Matins of Holy and Great Friday

The Byzantine Christian observance of Holy and Great Friday, which is formally known as The Order of Holy and Saving Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ, begins on Thursday night with the Matins of the Twelve Passion Gospels. Scattered throughout this Matins service are twelve readings from all four of the Gospels which recount the events of the Passion from the Last Supper through the Crucifixion and burial of Jesus. Some churches have a candelabrum with twelve candles on it, and after each Gospel reading one of the candles is extinguished.[44]

The first of these twelve readings[45] is the longest Gospel reading of the liturgical year, and is a concatenation from all four Gospels. Just before the sixth Gospel reading, which recounts Jesus being nailed to the cross, a large cross is carried out of the sanctuary by the priest, accompanied by incense and candles, and is placed in the center of the nave (where the congregation gathers) Sēmeron Kremātai Epí Xýlou:

Today He who hung the earth upon the waters is hung upon the Cross (three times).

He who is King of the angels is arrayed in a crown of thorns.

He who wraps the Heavens in clouds is wrapped in the purple of mockery.

He who in Jordan set Adam free receives blows upon His face.

The Bridegroom of the Church is transfixed with nails.

The Son of the Virgin is pierced with a spear.

We venerate Thy Passion, O Christ (three times).

Show us also Thy glorious Resurrection.[46][47]

The readings are:

- John 13:31-18:1 – Christ's last sermon, Jesus prays for the apostles.

- John 18:1–28 – The agony in the garden, the mockery and denial of Christ.

- Matthew 26:57–75 – The mockery of Christ, Peter denies Christ.

- John 18:28–19:16 – Pilate questions Jesus; Jesus is condemned; Jesus is mocked by the Romans.

- Matthew 27:3–32 – Judas commits suicide; Jesus is condemned; Jesus mocked by the Romans; Simon of Cyrene compelled to carry the cross.

- Mark 15:16–32 – Jesus dies.

- Matthew 27:33–54 – Jesus dies.

- Luke 23:32–49 – Jesus dies.

- John 19:25–37 – Jesus dies.

- Mark 15:43–47 – Joseph of Arimathea buries Christ.

- John 19:38–42 – Joseph of Arimathea buries Christ.

- Matthew 27:62–66 – The Jews set a guard.

During the service, all come forward to kiss the feet of Christ on the cross. After the Canon, a brief, moving hymn, The Wise Thief is chanted by singers who stand at the foot of the cross in the center of the nave. The service does not end with the First Hour, as usual, but with a special dismissal by the priest:

May Christ our true God, Who for the salvation of the world endured spitting, and scourging, and buffeting, and the Cross, and death, through the intercessions of His most pure Mother, of our holy and God-bearing fathers, and of all the saints, have mercy on us and save us, for He is good and the Lover of mankind.

Royal Hours

The next day, in the forenoon on Friday, all gather again to pray the Royal Hours,[48] a special expanded celebration of the Little Hours (including the First Hour, Third Hour, Sixth Hour, Ninth Hour and Typica) with the addition of scripture readings (Old Testament, Epistle and Gospel) and hymns about the Crucifixion at each of the Hours (some of the material from the previous night is repeated). This is somewhat more festive in character, and derives its name of "Royal" from both the fact that the Hours are served with more solemnity than normal, commemorating Christ the King who humbled himself for the salvation of mankind, and also from the fact that this service was in the past attended by the Emperor and his court.[49]

Vespers of Holy and Great Friday

In the afternoon, around 3 pm, all gather for the Vespers of the Taking-Down from the Cross,[50] commemorating the Deposition from the Cross. Following Psalm 103 (104) and the Great Litany, 'Lord, I call' is sung without a Psalter reading. The first five stichera (the first being repeated) are taken from the Aposticha at Matins the night before, but the final 3 of the 5 are sung in Tone 2. Three more stichera in Tone 6 lead to the Entrance. The Evening Prokimenon is taken from Psalm 21 (22): 'They parted My garments among them, and cast lots upon My vesture.'

There are then four readings, with Prokimena before the second and fourth:

- Exodus 33:11-23 - God shows Moses His glory

- The second Prokimenon is from Psalm 34 (35): 'Judge them, O Lord, that wrong Me: fight against them that fight against Me.'

- Job 42:12-20 - God restores Job's wealth (note that verses 18-20 are found only in the Septuagint)

- Isaiah 52:13-54:1 - The fourth Suffering Servant song

- The third Prokimenon is from Psalm 87 (88): 'They laid Me in the lowest pit: in dark places and in the shadow of death.'

- 1 Corinthians 1:18-2:2 - St. Paul places Christ crucified as the centre of the Christian life

An Alleluia is then sung, with verses from Psalm 68 (69): 'Save Me, O God: for the waters are come in, even unto My soul.'

The Gospel reading is a composite taken from three of the four the Gospels (Matthew 27:1-38; Luke 23:39-43; Matthew 27:39-54; John 19:31-37; Matthew 27:55-61), essentially the story of the Crucifixion as it appears according to St. Matthew, interspersed with St. Luke's account of the confession of the Good Thief and St. John's account of blood and water flowing from Jesus' side. During the Gospel, the body of Christ (the soma) is removed from the cross, and, as the words in the Gospel reading mention Joseph of Arimathea, is wrapped in a linen shroud, and taken to the altar in the sanctuary.

The Aposticha reflects on the burial of Christ. Either at this point (in the Greek use) or during the troparion following (in the Slav use):

Noble Joseph, taking down Thy most pure body from the Tree, wrapped it in pure linen and spices, and he laid it in a new tomb.[51]

an epitaphios or "winding sheet" (a cloth embroidered with the image of Christ prepared for burial) is carried in procession to a low table in the nave which represents the Tomb of Christ; it is often decorated with an abundance of flowers. The epitaphios itself represents the body of Jesus wrapped in a burial shroud, and is a roughly full-size cloth icon of the body of Christ. The service ends with a hope of the Resurrection:

The Angel stood by the tomb, and to the women bearing spices he cried aloud: 'Myrrh is fitting for the dead, but Christ has shown Himself a stranger to corruption.[51]

Then the priest may deliver a homily and everyone comes forward to venerate the epitaphios. In the Slavic practice, at the end of Vespers, Compline is immediately served, featuring a special Canon of the Crucifixion of our Lord and the Lamentation of the Most Holy Theotokos by Symeon the Logothete.[52]

Matins of Holy and Great Saturday

On Friday night, the Matins of Holy and Great Saturday, a unique service known as The Lamentation at the Tomb[53] (Epitáphios Thrēnos) is celebrated. This service is also sometimes called Jerusalem Matins. Much of the service takes place around the tomb of Christ in the center of the nave.[54]

A unique feature of the service is the chanting of the Lamentations or Praises (Enkōmia), which consist of verses chanted by the clergy interspersed between the verses of Psalm 119 (which is, by far, the longest psalm in the Bible). The Enkōmia are the best-loved hymns of Byzantine hymnography, both their poetry and their music being uniquely suited to each other and to the spirit of the day.[55]

They consist of 185 tercet antiphons arranged in three parts (stáseis or "stops"), which are interjected with the verses of Psalm 119, and nine short doxastiká ("Gloriae") and Theotókia (invocations to the Virgin Mary). The three stáseis are each set to its own music, and are commonly known by their initial antiphons: Ἡ ζωὴ ἐν τάφῳ, "Life in a grave", Ἄξιον ἐστί, "Worthy it is", and Αἱ γενεαὶ πᾶσαι, "All the generations". Musically they can be classified as strophic, with 75, 62, and 48 tercet stanzas each, respectively.[56]

The climax of the Enkōmia comes during the third stásis, with the antiphon "Ω γλυκύ μου ἔαρ", a lamentation of the Virgin for her dead Child ("O, my sweet spring, my sweetest child, where has your beauty gone?"). Later, during a different antiphon of that stasis ("Early in the morning the myrrh-bearers came to Thee and sprinkled myrrh upon Thy tomb"), young girls of the parish place flowers on the Epitaphios and the priest sprinkles it with rose-water. The author(s) and date of the Enkōmia are unknown. Their High Attic linguistic style suggests a dating around the 6th century, possibly before the time of St. Romanos the Melodist.[57]

The Evlogitaria (Benedictions) of the Resurrection are sung as on Sunday, since they refer to the conversation between the myrrh-bearers and the angel in the tomb, followed by kathismata about the burial of Christ. Psalm 50 (51) is then immediately read, and then followed by a much loved-canon, written by Mark the Monk, Bishop of Hydrous and Kosmas of the Holy City, with irmoi by Kassiani the Nun. The high-point of the much-loved Canon is Ode 9, which takes the form of a dialogue between Christ and the Theotokos, with Christ promising His Mother the hope of the Resurrection. This Canon will be sung again the following night at the Midnight Office.

Lauds follows, and its stichera take the form of a funeral lament, while always preserving the hope of the Resurrection. The doxasticon links Christ's rest in the tomb with His rest on the seventh day of creation, and the theotokion ("Most blessed art thou, O Virgin Theotokos...) is the same as is used on Sundays.

At the end of the Great Doxology, while the Trisagion is sung, the epitaphios is taken in procession around the outside the church, and is then returned to the tomb. Some churches observe the practice of holding the epitaphios at the door, above waist level, so the faithful most bow down under it as they come back into the church, symbolizing their entering into the death and resurrection of Christ. The epitaphios will lay in the tomb until the Paschal Service early Sunday morning. In some churches, the epitaphios is never left alone, but is accompanied 24 hours a day by a reader chanting from the Psalter.

When the procession has returned to the church, a troparion is read, similar to hthe ones read at the Sixth Hour throughout Lent, focusing on the purpose of Christ's burial. A series of prokimena and readings are then said:

- The first prokimenon is from Psalm 43 (44): 'Arise, Lord, and help us: and deliver us for Thy Name's sake.'

- Ezekiel 37:1-14 - God tells Ezekiel to command bones to come to life.

- The second prokimenon is from Psalm 9 (9-10), and is based on the verses sung at the kathismata and Lauds on Sundays: 'Arise, O Lord my God, lift up Thine hand: forget not Thy poor forever.'

- 1 Corinthians 5:6-8; Galatians 3:13-14 - St. Paul celebrates the Passion of Christ and explains its role in the life of Gentile Christians.

- The Alleluia verses are from Psalm 67 (68), and are based on the Paschal verses: 'Let God arise, and let His enemies be scattered.'

- Matthew 27:62-66 - The Pharisees ask Pilate to set a watch at the tomb.

At the end of the service, a final hymn is sung as the faithful come to venerate the Epitaphios.

Roman Catholic

Day of Fasting

The Catholic Church regards Good Friday and Holy Saturday as the Paschal fast, in accordance with Article 110 of Sacrosanctum Concilium.[58] In the Latin Church, a fast day is understood as having only one full meal and two collations (a smaller repast, the two of which together do not equal the one full meal)[59][60] – although this may be observed less stringently on Holy Saturday than on Good Friday.[58]

Services on the day

The Roman Rite has no celebration of Mass between the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday evening and the Easter Vigil unless a special exemption is granted for rare solemn or grave occasions by the Vatican or the local bishop. The only sacraments celebrated during this time are Baptism (for those in danger of death), Penance, and Anointing of the Sick.[61] While there is no celebration of the Eucharist, it is distributed to the faithful only in the Celebration of the Passion of the Lord, but can also be taken at any hour to the sick who are unable to attend this celebration.[62]

The Celebration of the Passion of the Lord takes place in the afternoon, ideally at three o'clock; however, for pastoral reasons (especially in countries where Good Friday is not a public holiday), it is permissible to celebrate the liturgy earlier,[63] even shortly after midday, or at a later hour.[64] The celebration consists of three parts: the liturgy of the word, the adoration of the cross, and the Holy communion.[65] The altar is bare, without cross, candlesticks and altar cloths.[66] It is also customary to empty the holy water fonts in preparation of the blessing of the water at the Easter Vigil.[67] Traditionally, no bells are rung on Good Friday or Holy Saturday until the Easter Vigil.[68]

The liturgical colour of the vestments used is red.[69] Before 1970, vestments were black except for the Communion part of the rite when violet was used.[70] If a bishop or abbot celebrates, he wears a plain mitre (mitra simplex).[71] Before the reforms of the Holy Week liturgies in 1955, black was used throughout.

The Vespers of Good Friday are only prayed by those who could not attend the Celebration of the Passion of the Lord.[72]

Three Hours' Agony

The Three Hours' Devotion based on the Seven Last Words from the Cross begins at noon and ends at 3 pm, the time that the Christian tradition teaches that Jesus died on the cross.[73]

Liturgy

The Good Friday liturgy consists of three parts: the Liturgy of the Word, the Veneration of the Cross, and the Holy Communion.

- The Liturgy of the Word consists of the clergy and assisting ministers entering in complete silence, without any singing. They then silently make a full prostration. This signifies the abasement (the fall) of (earthly) humans.[74] It also symbolizes the grief and sorrow of the Church.[75] Then follows the Collect prayer, and the reading or chanting of Isaiah 52:13–53:12, Hebrews 4:14–16, Hebrews 5:7–9, and the Passion account from the Gospel of John, traditionally divided between three deacons,[76] yet usually read by the celebrant and two other readers. In the older form of the Mass known as the Tridentine Mass the readings for Good Friday are taken from Exodus 12:1-11 and the Gospel according to St. John (John 18:1-40); (John 19:1-42).

- The Great Intercessions also known as orationes sollemnes immediately follows the Liturgy of the Word and consists of a series of prayers for the Church, the Pope, the clergy and laity of the Church, those preparing for baptism, the unity of Christians, the Jews, those who do not believe in Christ, those who do not believe in God, those in public office, and those in special need.[77] After each prayer intention, the deacon calls the faithful to kneel for a short period of private prayer; the celebrant then sums up the prayer intention with a Collect-style prayer. As part of the pre-1955 Holy Week Liturgy, the kneeling was omitted only for the prayer for the Jews.[78]

- The Adoration of the Cross has a crucifix, not necessarily the one that is normally on or near the altar at other times of the year, solemnly unveiled and displayed to the congregation, and then venerated by them, individually if possible and usually by kissing the wood of the cross, while hymns and the Improperia ("Reproaches") with the Trisagion hymn are chanted.[79]

- Holy Communion is bestowed according to a rite based on that of the final part of Mass, beginning with the Lord's Prayer, but omitting the ceremony of "Breaking of the Bread" and its related acclamation, the Agnus Dei. The Eucharist, consecrated at the Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday, is distributed at this service.[80] Before the Holy Week reforms of Pope Pius XII in 1955, only the priest received Communion in the framework of what was called the Mass of the Presanctified, which included the usual Offertory prayers, with the placing of wine in the chalice, but which omitted the Canon of the Mass.[78] The priest and people then depart in silence, and the altar cloth is removed, leaving the altar bare except for the crucifix and two or four candlesticks.[81]

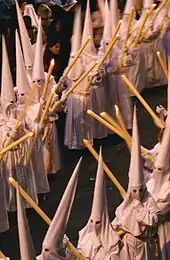

Stations of the Cross

In addition to the prescribed liturgical service, the Stations of the Cross are often prayed either in the church or outside, and a prayer service may be held from midday to 3.00 pm, known as the Three Hours' Agony. In countries such as Malta, Italy, Philippines, Puerto Rico and Spain, processions with statues representing the Passion of Christ are held.

In Rome, since the papacy of John Paul II, the heights of the Temple of Venus and Roma and their position opposite the main entrance to the Colosseum have been used to good effect as a public address platform. This may be seen in the photograph below where a red canopy has been erected to shelter the Pope as well as an illuminated cross, on the occasion of the Way of the Cross ceremony. The Pope, either personally or through a representative, leads the faithful through meditations on the stations of the cross while a cross is carried from there to the Colosseum.[82]

Novena to the Divine Mercy

The Novena to the Divine Mercy begins on that day and lasts until the Saturday before the Feast of Mercy. Both holidays are strictly connected, as the mercy of God flows from the Heart of Jesus that was pierced on the Cross.[83][84]

Protestant

Lutheran Church

In Lutheran tradition from the 16th to the 20th century, Good Friday was the most important religious holiday, and abstention from all worldly works was expected. During that time, Lutheranism had no restrictions on the celebration of the Eucharist on Good Friday; on the contrary, it was a prime day on which to receive the Eucharist, and services were often accentuated by special music such as the St Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach.[85]

_Johannespassion%252C_William-Byrd-Ensemble%252C_Apostelchor%252C_Andreas_Schmidt-Adolf%252C_Erwin_Sch%C3%BCtterle.jpg.webp)

More recently, Lutheran liturgical practice has recaptured Good Friday as part of the larger sweep of the great Three Days: Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Vigil of Easter. The three days remain one liturgy which celebrates the death and resurrection of Jesus. As part of the liturgy of the three days, Lutherans generally fast from the Eucharist on Good Friday. Rather, it is celebrated in remembrance of the Last Supper on Maundy Thursday and at the Vigil of Easter. One practice among Lutheran churches is to celebrate a tenebrae service on Good Friday, typically conducted in candlelight and consisting of a collection of passion accounts from the four gospels. While being called "Tenebrae" it holds little resemblance to the now-suppressed Catholic monastic rite of the same name.[86]

The Good Friday liturgy appointed in Evangelical Lutheran Worship, the worship book of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, specifies a liturgy similar to the revised Roman Catholic liturgy. A rite for adoration of the crucified Christ includes the optional singing of the Solemn Reproaches in an updated and revised translation which eliminates some of the anti-Jewish overtones in previous versions. Many Lutheran churches have Good Friday services, such as the Three Hours' Agony centered on the remembrance of the "Seven Last Words," sayings of Jesus assembled from the four gospels, while others hold a liturgy that places an emphasis on the triumph of the cross, and a singular biblical account of the Passion narrative from the Gospel of John.

Along with observing a general Lenten fast,[85] many Lutherans emphasize the importance of Good Friday as a day of fasting within the calendar.[5][6] A Handbook for the Discipline of Lent recommends the Lutheran guideline to "Fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday with only one simple meal during the day, usually without meat".[87]

Anglican Communion

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer did not specify a particular rite to be observed on Good Friday but local custom came to mandate an assortment of services, including the Seven Last Words from the Cross and a three-hour service consisting of Matins, Ante-communion (using the Reserved Sacrament in high church parishes) and Evensong. In recent times, revised editions of the Prayer Book and Common Worship have re-introduced pre-Reformation forms of observance of Good Friday corresponding to those in today's Roman Catholic Church, with special nods to the rites that had been observed in the Church of England prior to the Henrican, Edwardian and Elizabethan reforms, including Creeping to the Cross.

Methodist Church

Some Methodist denominations commemorate Good Friday with fasting,[4][88] as well as a service of worship based on the Seven Last Words from the Cross; this liturgy is known as the Three Hours Devotion as it starts at noon and concludes at 3 pm, the latter being the time that Jesus died on the cross.[89][90]

On Maundy Thursday, the altar and the cross are usually veiled in black for Good Friday, as black is the liturgical colour for Good Friday in the United Methodist Church. A wooden cross may sit in front of the bare chancel.[91]

Moravian Church

Moravians hold a Lovefeast on Good Friday as they receive Holy Communion on Maundy Thursday.

Communicants of the Moravian Church practice the Good Friday tradition of cleaning gravestones in Moravian cemeteries.[8]

Reformed Churches

In the Reformed tradition, Good Friday is one of the evangelical feasts and is thus widely observed with church services, which feature the Solemn Reproaches in the pattern of Psalm 78, towards the end of the liturgy.[92]

Other Christian traditions

Many Protestant churches hold an Interdenominational service with Lord's Supper. [93]

Associated customs

In many countries and territories with a strong Christian tradition such as Australia, Bermuda, Brazil, Canada, the countries of the Caribbean, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Malta, Mexico, New Zealand,[94][95][96] Peru, the Philippines, Portugal, the Scandinavian countries, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela, the day is observed as a public or federal holiday. In the United States, 12 states observe Good Friday as state holiday: Connecticut, Texas, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Tennessee, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Carolina and North Dakota. One associated custom is strict adherence to the Black Fast to 3pm or 6pm,[97] where only water can be consumed or restricted handout of bread, herbs and salt. St. Ambrose, St. Chrysostom and St. Basil attest to the practice.

The processions of the day, hymns "Crux fidelis" by King John of Portugal, and Eberlin's "Tenebrae factae sunt", followed by "Vexilla Regis" is sung, translated from Latin as the standards of the King advance, and then follows a ceremony that is not a real Mass, it is called the "Mass of the Pre-Sanctified.". This custom is respected also by forgoing the Mass, this is to take heed to the solemnity of the Sacrifice of Calvary. This is where the host of the prior day is placed at the altar, incensed, elevated so "that it may be seen by the people" and consumed. Germany and some other countries have laws prohibiting certain acts, such as dancing and horse racing, that are seen as profaning the solemn nature of the day.[10][11]

Australia

Good Friday is a holiday under state and territory laws in all states and territories in Australia.[98] Generally speaking, shops in all Australian states (but not in the two territories of the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory) are required to remain closed for the duration of Good Friday, although there are certain shops which are permitted to open and other shops can apply for exemptions. All schools and universities close on Good Friday in Australia, and Good Friday falls within the school holidays in most years in all states and territories except the Northern Territory, although many states now commence their school holidays in early April regardless of Easter. In 2018, for example, when Good Friday fell on 30 March, only Queensland and Victoria had school holidays which coincided with Good Friday.[99] The vast majority of businesses are closed on Good Friday, although many recreational businesses, such as the Sydney Royal Easter Show, open on Good Friday as among non-religious families Good Friday is a popular day to indulge in such activities.

Canada

.jpg.webp)

In Canada, Good Friday is a federal statutory holiday. In the province of Quebec "employers can choose to give the day off either on Good Friday or Easter Monday."[100]

Cuba

In an online article posted on Catholic News Agency by Alejandro Bermúdez on 31 March 2012, Cuban President Raúl Castro, with the Communist Party and his advisers, decreed that Good Friday that year would be a holiday. This was Castro's response to a request made personally to him by Pope Benedict XVI during the latter's Apostolic Visitation to the island and León, Mexico that month. The move followed the pattern of small advances in Cuba's relations with the Vatican, mirroring Pope John Paul II's success in getting Fidel Castro to declare Christmas Day a holiday.[101] Both Good Friday and Christmas are now annual holidays in Cuba.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, Good Friday was designated a public holiday in the Holidays Ordinance, 1875.[102] Good Friday continues to be a holiday after the transfer of sovereignty from the UK to China in 1997.[103] Government offices, banks, post offices and most offices are closed on Good Friday.

Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, Good Friday is not an official public holiday, but most non-retail businesses close for the day. Up until 2018 it was illegal to sell alcoholic beverages on Good Friday, with some exceptions, so pubs and off-licences generally closed.[104] Critics of the ban included the catering and tourism sector, but surveys showed that the general public were divided on the issue.[105][106] In Northern Ireland, a similar ban operates until 5 pm on Good Friday.[107]

Malaysia

Although Malaysia is a Muslim majority country, Good Friday is declared as a public holiday in the states of Sabah and Sarawak in East Malaysia as there is a significant Christian indigenous population in both states.[108]

Malta

The Holy Week commemorations reach their peak on Good Friday as the Roman Catholic Church celebrates the passion of Jesus. Solemn celebrations take place in all churches together with processions in different villages around Malta and Gozo. During the celebration, the narrative of the passion is read in some localities, while the Adoration of the Cross follows. Good Friday processions take place in Birgu, Bormla, Għaxaq, Luqa, Mosta, Naxxar, Paola, Qormi, Rabat, Senglea, Valletta, Żebbuġ (Città Rohan) and Żejtun. Processions in Gozo will be in Nadur, Victoria (St. George and Cathedral), Xagħra and Żebbuġ, Gozo.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, Good Friday is a legal holiday[109] and is a day of mandatory school closure for all New Zealand state and integrated schools.[110] Good Friday is also a restricted trading day in New Zealand, which means that unexempted shops are not permitted to open on this day.[111]

Philippines

In the predominantly Roman Catholic Philippines, the day is commemorated with street processions, the Way of the Cross, the chanting of the Pasyón, and performances of the Senákulo or Passion play. Some devotees engage in self-flagellation and even have themselves crucified as expressions of penance despite health risks and strong disapproval from the Church.[112]

Church bells are not rung and Masses are not celebrated, while television features movies, documentaries and other shows focused on the religious event and other topics related to the Catholic faith, broadcasting mostly religious content. Malls and shops are generally closed, as are restaurants as it is the second of three public holidays within the week.

After three o'clock in the afternoon (the time at which Jesus is traditionally believed to have died), the faithful venerate the cross in the local church and follow the procession of the Burial of Jesus.

In Cebu and many parts of the Visayan Islands, people usually eat binignit and biko as a form of fasting.[113][114]

Poland

In Polish churches, a tableau of Christ's Tomb is unveiled in the sanctuary. Many of the faithful spend long hours into the night grieving at the Tomb, where it is customary to kiss the wounds on the Lord's body. A life-size figure of Jesus lying in his tomb is widely visited by the faithful, especially on Holy Saturday. The tableaux may include flowers, candles, figures of angels standing watch, and the three crosses atop Mt Calvary, and much more. Each parish strives to come up with the most artistically and religiously evocative arrangement in which the Blessed Sacrament, draped in a filmy veil, is prominently displayed.

United Kingdom

In the UK, Good Friday was historically a common law holiday and is recognised as an official public holiday[118] (also known as a Bank Holiday). All state schools are closed and most businesses treat it as a holiday for staff; however, many retail stores now remain open. Government services in Northern Ireland operate as normal on Good Friday, substituting Easter Tuesday for the holiday.

There has traditionally been no horse racing on Good Friday in the UK. However, in 2008, betting shops and stores opened for the first time on this day[119] and in 2014 Lingfield Park and Musselburgh staged the UK's first Good Friday race meetings.[120][121] The BBC has for many years introduced its 7 am News broadcast on Radio 4 on Good Friday with a verse from Isaac Watts' hymn "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross".

The tradition of Easter plays include 1960 Eastertime performance of Good Friday: A Play in Verse (1916) Artists Ursula O'Leary (Procula), and William Devlin as Pontius Pilate, perform with the atmospheric sound effects of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. The Hugh Stewart production for the Home Service used soundware such as the EMS Synthi 100 and ARP Odyssey l.[122]

United States

In the United States, Good Friday is not a government holiday at the federal level; however, individual states, counties and municipalities may observe the holiday. Good Friday is a state holiday in Connecticut,[123] Delaware,[124] Florida,[125] Hawaii,[126] Indiana,[127] Kentucky (half-day),[128] Louisiana,[129] New Jersey,[130] North Carolina,[131] North Dakota,[132] Tennessee[133] and Texas.[134][135] State and local government offices and courts are closed, as well as some banks and post offices in these states, and in those counties and municipalities where Good Friday is observed as a holiday. Good Friday is also a holiday in the U.S. territories of Guam,[136] U.S. Virgin Islands[137] and Puerto Rico.[138]

The stock markets are closed on Good Friday,[139][140] but the foreign exchange and bond trading markets open for a partial business day.[141][142] Most retail stores remain open, while some of them may close early. Public schools and universities are often closed on Good Friday, either as a holiday of its own, or as part of spring break. The postal service operates, and banks regulated by the federal government do not close for Good Friday.[143]

In some governmental contexts Good Friday has been referred to by a generic name such as "spring holiday".[144][145][146] In 1999, in the case of Bridenbaugh v. O'Bannon, an Indiana state employee sued the governor for giving state employees Good Friday as a day off. The US Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the plaintiff, stating that the government could give state employees a paid day off when that day is a religious holiday, including Good Friday, but only so long as the state can provide a valid secular purpose that coincides with the obvious religious purpose of the holiday.[147]

Calculating the date

| Year | Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | April 10 | April 17 |

| 2021 | April 2 | April 30 |

| 2022 | April 15 | April 22 |

| 2023 | April 7 | April 14 |

| 2024 | March 29 | May 3 |

| 2025 | April 18 | April 18 |

| 2026 | April 3 | April 10 |

| 2027 | March 26 | April 30 |

| 2028 | April 14 | April 14 |

| 2029 | March 30 | April 6 |

| 2030 | April 19 | April 26 |

| 2031 | April 11 | April 11 |

| 2032 | March 26 | April 30 |

| 2033 | April 15 | April 22 |

| 2034 | April 7 | April 7 |

| 2035 | March 23 | April 27 |

Good Friday is the Friday before Easter, which is calculated differently in Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity (see Computus for details). Easter falls on the first Sunday following the Paschal Full Moon, the full moon on or after 21 March, taken to be the date of the vernal equinox. The Western calculation uses the Gregorian calendar, while the Eastern calculation uses the Julian calendar, whose 21 March now corresponds to the Gregorian calendar's 3 April. The calculations for identifying the date of the full moon also differ.

In Eastern Christianity, Easter can fall between 22 March and 25 April on Julian Calendar (thus between 4 April and 8 May in terms of the Gregorian calendar, during the period 1900 and 2099), so Good Friday can fall between 20 March and 23 April, inclusive (or between 2 April and 6 May in terms of the Gregorian calendar).

Cultural references

Good Friday assumes a particular importance in the plot of Richard Wagner's music drama Parsifal, which contains an orchestral interlude known as the "Good Friday Music".[148]

Memoration on Wednesday of the Holy Week

Some Baptist congregations,[149] the Philadelphia Church of God,[150] and some non-denominational churches oppose the observance of Good Friday, regarding it as a so-called "papist" tradition, and instead observe the Crucifixion of Jesus on Wednesday to coincide with the Jewish sacrifice of the Passover Lamb (which some/many Christians believe is an Old Testament pointer to Jesus Christ). A Wednesday Crucifixion of Jesus allows for him to be in the tomb ("heart of the earth") for three days and three nights as he told the Pharisees he would be (Matthew 12:40), rather than two nights and a day (by inclusive counting, as was the norm at that time) if he had died on a Friday.[151][152]

Further support for a Wednesday crucifixion based on Matthew 12:40 includes the Jewish belief that death was not considered official until the beginning of the fourth day, which is disallowed with the traditional Friday afternoon to Sunday morning period of time. As "the Jews require a sign" (1 Corinthians 1:22), the resurrection of Christ is thus invalidated with the shorter interval, since it can thus be claimed that Christ could have only 'swooned,' rather than actually died.

See also

References

- The Chambers Dictionary. Allied Publishers. 2002. p. 639. ISBN 978-81-86062-25-8. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- Elizabeth Webber; Mike Feinsilber (1999). Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Allusions. Merriam-Webster. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-87779-628-2. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- Franklin M. Segler; Randall Bradley (2006). Christian Worship: Its Theology And Practice. B&H Publishing Group. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8054-4067-6. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles Anderson (1883). The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary for General Knowledge. D. Appleton and Company. p. 101.

The Protestant Episcopal, Lutheran, and Reformed churches, as well as many Methodists, observe the day by fasting and special services.

- Pfatteicher, Philip H. (1990). Commentary on the Lutheran Book of Worship: Lutheran Liturgy in Its Ecumenical Context. Augsburg Fortress Publishers. pp. 223–244, 260. ISBN 978-0800603922.

The Good Friday fast became the principal fast in the calendar, and even after the Reformation in Germany many Lutherans who observed no other fast scrupulously kept Good Friday with strict fasting.

- Jacobs, Henry Eyster; Haas, John Augustus William (1899). The Lutheran Cyclopedia. Scribner. p. 110.

By many Lutherans Good Friday is observed as a strict fast. The lessons on Ash Wednesday emphasize the proper idea of the fast. The Sundays in Lent receive their names from the first words of their Introits in the Latin service, Invocavit, Reminiscere, Oculi, Lcetare, Judica.

- "What is the significance of Good Friday?". The Free Press Journal. 2 April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "PHOTOS: Cleaning Moravian gravestones, a Good Friday tradition". Winston-Salem Journal. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 36, Issue 214. Harper & Brothers. 1868. p. 521.

In England Good-Friday and Christmas are the only close holidays of the year when the shops are all closed and the churches opened.

- Petre, Jonathan (21 March 2008). "Good Friday gambling anger churches". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

Bookmakers estimate that thousands of shops will be operating, even though Good Friday is one of three days in the year when no horse racing takes place.

- Stevens, Laura (29 March 2013). "In Germany, Some Want to Boogie Every Day of the Year". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

Every year on Good Friday, Germany becomes a little like the fictional town in the movie 'Footloose' – dancing is verboten. The decades-old 'Tanzverbot,' or dance ban, applies to all clubs, discos and other forms of organized dancing in all German states.

- "Good Friday – Definition of Good Friday in the American Heritage Dictionary". Yourdictionary.com. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Home: Oxford English Dictionary". Oed.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Svensk etymologisk ordbok 434". runeberg.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Ireland, The Educational Company of (10 October 2000). Irish-English/English-Irish Easy Reference Dictionary. Roberts Rinehart. ISBN 9781461660316 – via Google Books.

- Mark, Colin B. D. (2 September 2003). The Gaelic-English Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 9781134430604 – via Google Books.

- Wales, National Library of (15 April 1946). "Cylchgrawn Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru". National Library of Wales – via Google Books.

- Matthew 26:14–16)

- John 18:1–24

- Matthew 26:57–66

- Luke 23:1–2

- John 18:31

- Luke 23:3–16

- Mark 15:6–14

- Matthew 27:19

- John 19:1–9

- Matthew 27:24–26

- John 19:17–22)

- Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:13; Luke 23:44

- Matthew 27:45; Mark 15:34

- Matthew 27:45–54

- Luke 23:50–52

- John 19:39–40

- Mark 15:44

- John 19:34

- Mark 15:45

- Matthew 27:59–60

- John 3:1

- Matthew 27:60

- Luke 23:54–56

- Gerald O'Collins, Edward G. Farrugia (2013). A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Paulist Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-587-68236-0.

- There is a wide variety of uses regarding the liturgical colors worn during Great Lent and Holy Week in the Rite of Constantinople.

- Bulgakov, Sergei V. (1900). "Great Friday". Handbook for Church Servers (PDF) (2nd ed.). Kharkov: Tr. Archpriest Eugene D. Tarris. p. 543. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Matins for Great and Holy Friday" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- John 13:31–18:1

- Archimandrite Kallistos (Ware) and Mother Mary (2002). "Service of the Twelve Gospels". The Lenten Triodion. South Cannan, PA: St. Tikhon's Seminary Press. p. 587.

- Today He who hung the earth upon the waters Archived 7 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine Chanted by the Byzantine Choir of Athens

- "Royal Hours". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "What happened on Good Friday? The Easter story explained". Metro. 30 March 2018. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Vespers of the Taking-Down from the Cross". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Ware, Kallistos; Mother Mary (1977). The Lenten Triodion. South Canaan, PA: St Tikhon's Seminary Press. p. 616. ISBN 1-878997-51-3.

- "Good Friday | Definition, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "The Lamentation at the Tomb". YouTube. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "History of Good Friday – Good Friday Story, Eastergoodfriday.com". www.eastergoodfriday.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Maunder, Chris (7 August 2019). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879255-0.

- Maunder, Chris (7 August 2019). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879255-0.

- Maunder, Chris (7 August 2019). The Oxford Handbook of Mary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879255-0.

- "Sacrosanctum concilium". Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Fast & Abstinence". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- "Fasting and Abstinence" (PDF). Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales. 24 January 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- Roman Missal: Good Friday, 1.

- The Holy Week Missal, Friday of the Passion of the Lord No. 2

- "V. Good Friday". The Catholic Liturgical Library. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- The Holy Week Missal, Friday of the Passion of the Lord No. 4

- The Holy Week Missal, Friday of the Passion of the Lord No. 4

- The Holy Week Missal, Friday of the Passion of the Lord No. 3

- "Removing Holy Water During Lent. Letter of the Congregation for Divine Worship". 14 March 2003. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- "Good Friday – Easter/Lent". Catholic Online. 12 January 2018. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- The Holy Week Missal, Friday of the Passion of the Lord No. 5

- 1962 edition of the Roman Missal Archived 26 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Caeremoniale Episcoporum, 315.

- The General Instruction on the Liturgy of the Hours, No. 209

- Robert Barron. "Tre Ore - The Three Hours' Agony". Word on Fire. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

'The Three Hours' Agony' or Tre Ore is a liturgical service held on Good Friday from noon until 3 o'clock to commemorate the Passion of Christ. Specifically, it refers to the three hours that Jesus hung on the Cross and includes a series of homilies on the seven last words spoken by Christ.

- Roman Missal, "Good Friday", Celebration of the Passion of the Lord, n. 5.

- Circular Letter Concerning the Preparation and Celebration of the Easter Feasts, V. Good Friday Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 16 January 1988, Sacred Congregation for Divine Worship.

- Congregation of Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, Paschale Solemnitatis, III, n. 66 (cf. n. 33)

- Roman Missal: Good Friday, 7–13.

- "Compendium of the 1955 Holy Week Revisions". Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Roman Missal: Good Friday, 14–21.

- Roman Missal: Good Friday, 22–31.

- Roman Missal: Good Friday, 32–33.

- "Traditional Via Crucis at the Colosseum in Rome". ITALY Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- "Sanctuary of the Divine Mercy". Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Saint Faustina". Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- Gassmann, Günther; Oldenburg, Mark W. (2011). Historical Dictionary of Lutheranism. Scarecrow Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0810874824.

In many Lutheran churches, the Sundays during the Lenten season are called by the first word of their respective Latin Introitus (with the exception of Palm/Passion Sunday): Invocavit, Reminiscere, Oculi, Laetare, and Judica. Many Lutheran church orders of the 16th century retained the observation of the Lenten fast, and Lutherans have observed this season with a serene, earnest attitude. Special days of eucharistic communion were set aside on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday.

- "A Word About Tenebrae |". Historiclectionary.com. 22 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Weitzel, Thomas L. (1978). "A Handbook for the Discipline of Lent" (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Bays, Daniel H; Wacker, Grant (2010). The Foreign Missionary Enterprise at Home: Explorations in North American Cultural History. University of Alabama Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0817356408.

- The United Methodist Book of Worship: Regular Edition Black. United Methodist Publishing House. 2016. p. 365. ISBN 978-1426735004.

- "Christians mark Good Friday". The Daily Reflector. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- The United Methodist Book of Worship: Regular Edition Black. United Methodist Publishing House. 2016. p. 363. ISBN 978-1426735004.

...a plain wooden cross may now be brought into the church and placed in the sight of the people. ... During Silent Meditation and The Reproaches, persons may be invited to come forward informally to kneel briefly before the cross or touch it.

- "Good Friday". Reformed Church in America. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Britannica, Encyclopedia of World Religions, Encyclopaedia Britannica, USA, 2008, p. 309

- Holidays Act 2003 (New Zealand), Section 17 Days that are public holidays Archived 5 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Shop Trading Hours Act Repeal Act 1990 (New Zealand), Section 3 Shops to be closed on Anzac Day morning, Good Friday, Easter Sunday, and Christmas Day Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Broadcasting Act 1989 (New Zealand), Section 79A Hours during which election programmes prohibited Archived 26 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Section 81 Advertising hours Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Black Fast". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Public holidays – australia.gov.au". Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "School Term Dates". australia.gov.au. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Statutory holidays in Canada both national and provincial". Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- "Cuban authorities declare Good Friday 2012 a holiday". Catholic News Agency. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "The Holidays Ordinance, 1875" (PDF). 7 July 1875. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 April 2021.

- "GovHK: General holidays for 2007 – 2022". Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- Gleeson, Colin (2 April 2010). "You can have a pint today – if you know where to look". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Hade, Emma Jane (2 April 2015). "Good Friday alcohol ban still splits public as only half want it abolished". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- 'Times have changed a lot' – one of Ireland's oldest barmaids (98) pulls pints for the first time on Good Friday Archived 3 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine independent.ie, 30 March 2018

- Coulter, Peter (23 March 2016). "Pub owners frustrated at assembly failure to change Easter opening hours". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Michael Ipgrave (2008). Building a Better Bridge: Muslims, Christians, and the Common Good : a Record of the Fourth Building Bridges Seminar Held in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, May 15–18, 2005. Georgetown University Press. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-1-58901-731-3. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Public holidays and anniversary dates". NZ Government. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "PMore information on setting term dates, holidays and closing days". 31 July 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Restricted shop trading days » Employment New Zealand". Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Marks, Kathy (22 March 2008). "Dozens ignore warnings to re-enact crucifixion". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- Izobelle T. Pulgo, "Binignit: A Good Friday Cebuano soul food Archived 15 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine", Cebu Daily News, 23 March 2016.

- Deralyn Ramos, "Holy Week in the Philippines Archived 27 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine", Tsuneishi Balita, March 2013, p. 4.

- "Holidays Act (Chapter 126)". Singapore Statutes Online. 1999. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- "Holidays Act (Chapter 126), Legislative History". Singapore Statutes Online. 1999. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- Rohrer, Finlo (1 April 2010). "How did hot cross buns become two a penny?". BBC News magazine. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "Bank holidays and British Summer Time". Directgov. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Petre, Jonathan (21 March 2008). "Good Friday gambling angers churches". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "Lingfield: £1m Good Friday fixture to be held at Surrey racecourse". BBC News. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- Brown, Craig (11 October 2013). "Musselburgh to host historic Good Friday racing". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- John Masefield Society: Good Friday: A Play in Verse (1916) Archived 12 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Connecticut. "Legal State Holidays". CT.gov. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- "Delaware – Office of Management and Budget – State of Delaware Holidays". Delawarepersonnel.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Title XXXIX Commercial Relations Section 683.01 Legal holidays". onecle.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014.

- "Hawaii State Holidays for 2014". Miraclesalad.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Secretary of State: 2011 Indiana State Holidays". In.gov. Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Holidays". Personnel.ky.gov. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Sandra G. Gillen, CPPB. "2014 State Holidays Calendar Observed by OSP". Doa.louisiana.gov. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "The Official Web Site for The State of New Jersey | State Holidays". Nj.gov. Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "N.C. State Government Holiday Schedule for 2013 and 2014". Ic.nc.gov. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "North Dakota State Holidays 2014". The Holiday Schedule. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Official State Holidays". TN.gov. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- In addition to holidays where offices are closed, Texas also has "partial staffing holidays" (where offices are required to be open for public business, but where employees may take it off as a holiday) and "optional holidays" (where an employee may take off in lieu of taking off on a partial staffing holiday; Good Friday is an optional holiday).

- "Texas State Holidays". The State of Texas. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Guam Public Holidays 2012 (Oceania)". Qppstudio.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "US Virgin Islands Public Holidays 2012 (Americas/Caribbean)". Qppstudio.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Puerto Rican Holidays". Topuertorico.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "NYSE: Holidays and Trading Hours". nyse.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Stock Market Holidays". Money-zine.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "CME Group Chicago Trading Floor Holiday Schedule for 2015" (PDF). CME Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Holiday Schedule". sifma.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Federal Holidays". Opm.gov. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Archived 14 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Goldman, Russell (29 March 2010). "Iowa Town Renames Good Friday to 'Spring Holiday'". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Villarreal, Abe (17 April 2014). "Spring Holiday – Western New Mexico University". Wnmu.edu. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Good Friday in the United States". Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "Good Friday Music – Dictionary definition of Good Friday Music". Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Landis, L. K. (8 June 1998). "Proof for a Wednesday Crucifixion". King James Bible Baptist Church, Ladson, South Carolina. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "The Resurrection Was Not on Sunday". thetrumpet.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009.

- "The Cradle & the Cross (original)". thebereancall.org. 1 December 1992. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Cult, Cults, Abuse by Religions, Abuse Recovery Discussion & Resources, Peer-Support, Legal support". factnet.org. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009.

Further reading

- Bellarmine, Robert (1902). . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- Gilmartin, Thomas Patrick (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- The Eastern Orthodox commemoration of Holy Friday (archived 7 June 2011)

- Great Friday instructions from S. V. Bulgakov's Handbook for Church Servers (Russian Orthodox Church) (archived 3 March 2016)

- Episcopal Good Friday Service

- Who, What, Why: Why is Good Friday called Good Friday?

- Good Friday

- "Mayor wants 'draconian' Good Friday booze ban lifted before 1916 centenary". Independent.ie. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2016.