Horses in Togo

The minor presence of horses in Togo comes out of a few breedings and practices of equestrianism represented, at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century, in the region of Mango and in the north of the current country. Horses were introduced at that time thanks to the Tem, who were the founders of a small kingdom that focused on the use of rifles and cavalry. The distribution of horses in the south is much more recent, as breeding was very limited due to the presence of the tsetse fly. After sporadic imports of horses by German and French colonial troops, a diplomatic gift from Niger in the 1980s allowed the creation of the first Togolese honorary cavalry regiment. The use of the horse-drawn vehicle has always been unknown in Togo.

With an equine herd of about 2,000 horses, Togolese equestrian practices are exclusively for parades. This tradition takes place during the Adossa festival, an annual customary ceremony that attracts around 200 riders to the town of Sokodé. Horses are also used in Togolese fetish practices.

History

Togo is not a country with an equestrian tradition,[1] being one of the West African countries that have neglected horse breeding.[2]

Pre-colonial period

Robin Law's reference work, The Horse in West African History, published in 1980 and republished with additions in 2018 (in French: Le cheval dans l'histoire d'Afrique de l'Ouest), does not mention the presence of horses on the Togolese coast during the pre-colonial period and the situation inland remains unknown until the 19th century, due to the absence of sources.[3] Another difficulty is the absence of a large African kingdom in Togo, which could have been written about by travelers.

In his Histoire des Togolais, Nicoué Ladjou Gayibor (assistant professor at the University of Benin) mentions the practice of equestrianism by the nomadic Koto-Koli (or Tem) who settled near the present-day town of Sotouboua, near the Mono River, in the late 19th century.[4] He also mentions the success of the Chakosi people led by Na Biema, who created a small kingdom around Mango at the same time, after having subdued the natives.[5] Nicoué attributes this success to the introduction of rifles and the use of horses, which they may have learned from a neighboring tribe: the Gondja or Mamproussi.[5] In fact, according to Siriki Ouattara's thesis, the Chakosi people of present-day Ivory Coast never knew the use of horses.[6]

Zarma riders and mercenaries, the Semassi, are known for having operated on Togolese territory on behalf of slave traders between 1883 and 1887. After having been co-opted by the Tem, they kidnap children on the roads at the level of Fazao mountains, or further south, and place up to two or three of them on the same horse before fleeing.[7]

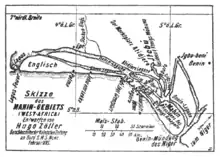

Observations of Hugo Zöller in 1884

The German explorer and journalist Hugo Zöller, who visited Togo in 1884, noted the absence of the use of pack horses (contrary to what he had observed in North Africa), which is why the goods were essentially carried by men.[8] In the localities under the German protectorate that he visited, he pointed out that "One finds neither cattle nor horses. Our domestic animals are just pigs, sheep, goats, chickens and, from time to time, skinny dogs".[9]

By contrast, Europeans and colonial troops did use horses. Consul Randad (Togo's consul in 1884) rode a horse for his travels, especially to a Hausa camp.[10] According to Hugo Zöller, the city of Lomé (located on the Togolese coast) had only two horses in 1884, and that of Baguida had none.[10] These were ponies adapted to the local climate, purchased for 200 or 300 marks each, and exported from the market of Salaga, then located ten days inland, via Keta (both located in present-day Ghana).[11] These two horses are fed on maize and abundant local vegetation, growing within fifteen minutes of their stables.[11] Each of these horses has a personal groom, the first had a Krou young man and the second had a Hausa young man.[11]

The Togolese terrain is unfavorable for traveling by horse, and it is considered dangerous because for the most part, it consists of man-sized paths, sand, muddy silt, or very tall, sharp grass.[12] However, the Savanna region offers abundant equine food.[13]

Finally, Zöller reports the interest of the inhabitants, especially the women, in his and the consul's passage, without being able to determine whether this interest is due to the unusual presence of horses in this region, or to that of white men.[14] In Agoè, he writes that "the appearance of our horses caused almost more sensation than our own presence. They were constantly assailed by a group of women and girls who kept shouting 'enongto' which means “Oh, how pretty".[15]

From World War I to the end of the colonial period

The proliferation of firearms, as well as the disappearance of African kingdoms and small chiefdoms that once lived off the slave trade, led to an overall decline in the number of horses in West Africa. That is the reason why this animal, once a military asset, became the prerogative of chiefs or merchants who made it a symbol of their power or wealth.[16]

During World War I, Duranthon entered Togoland from the north with 50 lightly armed cavalry goumiers and managed to recruit others on the spot to chase the Germans, bringing the total number of cavalrymen to 170, most of whom were armed with spears, and about 30 armed with rifles.[17]

In 1926, the French colonial administration described a practice of horse breeding in northern French Togoland, where a small, very resistant, and hardy horse was raised in "good conditions".[18] The colonial administration does not count any horses in Sokodé, but reports the presence of 676 horses in Mango, a figure that is probably underestimated because the inhabitants tend to hide their animals. Jean Eugène Pierre Maroix described the presence in 1938 of a "small but very resistant Togolese horse [that] was only found in the north".[19] This observation was shared by various French settlers in Togo during the 1930s, one of whom wrote that the Mossi people of northern Togo knew how to ride, while the ethnic groups of the south were unaware of horses.[20] Taxes were applied to horses entering or leaving the country's borders.[21]

In 1937, the annual census of African livestock reported only four horses in all of French Togoland.[22] In 1943, L'Encyclopédie coloniale et maritime described a "small horse well adapted to the environment, reminiscent of the poney du Logone" under the name of Kotokoli, which was 1.10 to 1.20 meters long.[23]

From independence to the present day

Among the Bassari of northern Togo, according to Robert Cornevin (1962), "horses are frequently of little appearance but are resistant and therefore sufficient. The people appear to be good horsemen, well trained in the use of weapons".[24] The ladjo (Muslim customary chief) traditionally receives a horse at his investiture, which takes place at his home; his horse is slaughtered at the time of his death.[25] This custom of using the horse as a symbol of chiefdom is particularly prevalent among the Kabye ethnic group.[26] Only a person with an important public function, or a power "invested by the ancestors to preside over the destiny of a clan or tribe," could own a horse.[27]

In the 1980s, most people in Lomé had never seen a horse in their lives.[1] The establishment of horses in the Togolese capital came in part from a diplomatic gift of a dozen small animals from Nigeria's President Seyni Kountché to Gnassingbé Eyadéma.[1] According to the French rider and editor Jean-Louis Gouraud, this gave rise to the Togolese cavalry regiment in the 1980s.[28] Horse breeding declined during the second half of the 20th century, with a reduction of one-third of the estimated herd between 1977 (3,000) and 1989 (2,000).[29] Some historical horse-breeding regions gave up the use of this animal altogether, for various reasons.[29] In Mango and Dapaong, livestock breeding motivated entirely by hunting is losing interest with the creation of protected areas and national parks in which hunting is prohibited, prompting their owners to sell their hunting horses to Benin and Ghana.[30]

Tikpi Atchadam, a political opponent of the ruling Gnassingbé family, created the Pan-African National Party in 2014, with the color red and a horse rearing, a Tem warrior emblem,[31] as symbols, a choice he justifies by "its strength, courtesy, and elegance".[32] In this context of political opposition, in 2018, the equestrian statue of a mounted warrior, in Kparatao, was riddled with bullets during a night clash.[33] In April 2019, Togolese President Faure Gnassingbé received a white horse and a boubou from executives of the Cinkassé Prefecture in Timbu, so that he would win a "clean and total victory" in the 2020 presidential elections.[34]

Customs

Only male horses are traditionally ridden, the females being reserved for breeding.[35] The use of horses in Togo focuses essentially on prestige and parades.[36] The most famous festive event around the horse is the Adossa festival, or Cutlery festival, organized every year in Sokodé.[37] The largest gathering of horses in Togo attracts about 200 richly caparisoned riders, sometimes coming from very distant regions.[37] It is also the occasion for horse races and dances.[36]

Personalities can be honored by the presence of a horse, as the horse is seen as an animal of prestige.[38] Shéyi Emmanuel Adébayor, a Togolese soccer striker, was carried on a horse in Sokodé.[39]

The horse is not perceived as a transport animal, a sport animal, or a draught animal, although there has been a recent awareness of its physical capacities.[2][40] It can be ridden for routine travel between villages and to visit family members or parties.[41] It is also used for transporting water or foodstuffs.[41] In the Savanna region, it is used to transport crops, people, or various goods and materials.[27]

Horse-drawn vehicles have never been developed in Togo, despite the existence of this practice in neighboring countries.[42] In the absence of a culture of transmission of the training and use of draft animals, local farmers prefer to use motorized vehicles. Horse meat is consumed by the local population, these animals being, when old, often reformed by selling them at low prices for this purpose.[27]

In 1989, Jean-Louis Gouraud proposes a circuit of equestrian tourism in Togo,[43] following a north–south[37] axis between Lomé and Fazao.[44] Some horse riding activities on the Togolese beach are possible;[45] in 1968, there were horse rides in a coconut grove.[46] The equestrian facility "Hymane épique club" in Lomé offers various equestrian sports and organized a horse-ball discovery on 15 September 2019.[47] Every 13 January, the Togolese national holiday is the occasion of the parade of a regiment mounted with 200 horses.[45] This regiment also takes part in other military parades.[48] It has a dissuasive function, allowing among other things to disperse demonstrations.[49]

A part of the use of horses in Togo focuses on the production of antivenom, antibodies being collected in the animal's blood after it has been injected with a small dose of snake venom.[50]

Breeding

2.jpg.webp)

Horse breeding has never been a priority in Togo's policies.[40] In modern Togo (1980), it was limited to the extreme north of the country;[51] in 1991, it was practiced by private breeders as well as by the State, in a poorly organized manner,[52] without any promotional structure.[48] The Togolese ethnic groups that traditionally breed horses are the Koto-Koli (or Tem) and the Moba.[26] In the Muslim town of Bassar, the Bassari people justify their refusal to raise horses by the fact that their ancestors were defeated by horses ridden by an invading tribe from the West.[53]

Horse breeding is mostly practiced by farmers, but on a very small scale compared to other forms of breeding.[26] Village chiefs generally own between 1 and 5 horses; larger farms are privately owned for commercial purposes, such as the "Bena Development" farm.[48] State-owned stables are generally better maintained and supplied than those of private owners; the latter let their horses graze on available grassland.[54] As a result, problems of undernourishment of the horses are frequent, with a lack of mineral and food supplements.[53] Horse breeding is entirely natural, and mares foal without receiving special veterinary care.[41]

Size and distribution of the herd

The horse population in Togo is restricted to about 2,000 individuals according to the Delachaux guide (2014);[36] Dr. Donguila Belei's veterinary thesis also cites a herd of 2,000 horses in 1991.[29]

Environmental constraints limit it; the north of the country is mountainous, and the south has vast grazing lands, but is invaded by parasites deadly to horses.[55] In the Savanna region in the north, breeders must manage forage supply and drought.[56] The Togolese regions with the most horses in 1991 were, in order: Kara, the Savannas,[29] the maritime region, the Plateaux region (mainly due to the establishment of the "Bena Développement" farm), and the central region, which had fewer than 15 horses, but which were very unevenly distributed.[57] More recently, farms have been established in the Lomé region.[36] Kara and Pya are home to the Togolese army's mares.[37] The latter, which consisted of about 200 horses in 1991, is the country's leading equine breeding operation, despite various constraints that have led to a reduction in the number of animals.[48] The mares are bred in Kara, and the stallions in Bafilo.[48]

The equestrian center in Lomé alone has more than 20 horses.[48]

Types of horses raised

Belei[40] and Gouraud[58] point out the absence of a purely Togolese breed. Jean-Louis Gouraud describes local horses that are rather small and narrow, with slender thighs, a strongly arched head profile, and a wide variety of coat colors.[35][59] Donguila Belei cites horses resulting from numerous crosses and breeds between the Barb, Dongola, Arabian, and ponies.[40]

The Delachaux guide (2014) and the CAB International reference book (2016) cite the so-called Koto-koli breed as being raised in northern Togo and Benin.[36][60] According to Law, this pony is bred in the northern mountains of the country.[61] According to Jean-Louis Gouraud, Togolese horses are mainly sourced from neighboring countries, including Niger, Burkina Faso, and Ghana.[58]

Diseases and parasites

The main obstacle to horse breeding is the presence of the tsetse fly (or glossina), which carries a fatal disease for horses, especially in the south of the country,[62] near coconut groves, or forest areas.[26] Other insects, notably the Tabanidae, cause trypanosomiasis.[63]

Attempts to immunize West African horses and donkeys were made during the 1900s.[64] In particular, until 1909, an international technical assistance service of the University of Tuskegee in Alabama (United States) tried to establish the horse in Togo because of its value as a working animal; to this end, they advocated dressing horses during the day "in something that protects them," adding that "since the price of a horse is 60, 70 or 80 Marks, assuming the horse lives and works only 60 days," using a horse for plowing will be more profitable than paying a daily wage to local workers.[65]

In 1991, Dr. Donguila Belei, a veterinarian, wrote his thesis on parasitosis and infections affecting horses in Togo.[2] The incidence of trypanosomiasis is decreasing due to the eradication programs of the insect vectors, which also infect cattle.[66] Local breeds of horses are more resistant than imported ones.[66] Two forms are known in Togolese horses: nagana (caused by Trypanosoma brucei) and dourine (caused by Trypanosoma equiperdum).[67] Babesiosis has also been observed in Togolese stables.[68] Type 9 African horse sickness has also been observed,[69] mainly in the Savanna and Kara regions,[70] making Togo a team focus.[71] However, the country is not affected by Equine infectious anemia.[72] No specific protection measures against contagious diseases and parasites had yet been implemented.[73]

The status of zoonotic diseases affecting horses in Togo remains unknown.[74] Togo is one of the clusters of epizootic lymphangitis during the rainy season, with animals getting sick and becoming contagious if they have wounds.[75]

Culture

The horse was once of primary importance in Togolese society as a "sacred and mythological animal" and a symbol of honor and was not exploited for economic purposes.[41]

According to Togo political scientist Comi M. Toulabor, a horse's tail, when owned by an important religious or political figure, has an occult or symbolic significance in Togolese customary societies as an object to ward off evil occult forces.[76] In 1884, Hugo Zöller described a cult in the town of Bè (known for its fetishists) to Njikpla, the god of the shooting star and of war and the most important of the secondary gods, who is represented seated on horseback and dressed in European style.[77] He also points out the omnipresence of animal drawings in bright paint on Togolese homes, most of which he says depict a stylized horse, which he explains by the fact that "the horse [is], of all our domestic animals, the one that imposes the most on the blacks, for the good reason that it is very rare here."[78]

In the tales and myths of Togo compiled by Gerhard Prilop, Yao the orphan chooses a white horse that galloped to seven hills before returning to him, which then helps him in his adventures.[79] In the tale of Halasiba, the latter, having made a little fortune, buys a white horse to sacrifice it: the sky lights up at night thanks to the tail of this sacrificed white horse, which has been transformed into a constellation.[80] The district of Gkolonghioro in Agbandi (Diguina), whose name means "under the shea tree", is said to have been founded by a cattle breeder, Agbaniwul, at the place where he tied his horse.[81]

The honorific status of the horse tends to diminish, due to its possession by rural farmers, and its exploitation for economic purposes.[41] The limbs of modern Togolese horses are often dyed with henna.[59]

See also

References

- Gouraud (2002, p. 64)

- Belei (1991, p. 1)

- Law (2018)

- Gayibor (2011a, p. 232-233)

- Gayibor (2011a, p. 348)

- Outtara, Siriki (1986). Les Anofwe de Côte d'Ivoire des origines à la conquête coloniale (in French). Doctoral thesis. Université de Paris I. p. 535.

- Gayibor (2011a, p. 533)

- Zöller (1990, p. 12)

- Zöller (1990, p. 114)

- Zöller (1990, p. 24)

- Zöller (1990, p. 25)

- Zöller (1990, p. 25,26,109)

- Zöller (1990, p. 26)

- Zöller (1990, p. 37)

- Zöller (1990, p. 110)

- Mauny, Raymond (1980). "Law (Robin) : The horse in West African History. The rôle of the horse in the societies of pre-colonial West Africa". Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire. 67 (248): 388–389.

- Gayibor (2011b, p. 88-89)

- Bonecarère; Marchand (1926). Le Togo et le Cameroun. Les pays africains sous mandat (in French). La Vie technique, industrielle, agricole & coloniale. p. 26.

- Pierre Maroix, Jean Eugène (1938). Le Togo : pays d'influence français (in French). Larose éditeurs. pp. 38, 136.

- Martet, Jean (1995). "Chroniques anciennes du Togo". Regards français sur le Togo des années 1930 (in French). Mission ORSTOM du Togo. p. 264. ISBN 2906718505.

- "Le Togo". fr. Dubois et Bauer ; agence économique de l'Afrique occidentale Française. 1992.

- "Annuaire de Statistiques Agricoles Et Alimentaires". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (in French). 9 (1): 120. 1955.

- Léonard Guernier, Eugène; Froment-Guieysse, Georges (1943). L'Encyclopédie coloniale et maritime : Cameroun. Togo (in French). Vol. 6. Togo: L'Encyclopédie coloniale et maritime. p. 497.

- Cornevin, Robert (1962). Les Bassari du nord Togo. Mondes d'Outre-mer (in French). Éditions Berger-Levrault. pp. 66, 156.

- Gayibor (2011a, p. 380)

- Belei (1991, p. 8)

- Belei (1991, p. 16)

- Gouraud (2017)

- Belei (1991, p. 9)

- Belei (1991, p. 20)

- Châtelot, Christophe (26 September 2017). "A Lomé, dans le quartier d'Agoé, l'opposition à Faure Gnassingbé s'étend". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Tikpi Atchadam, l'opposant que personne n'a vu venir au Togo". Le Monde. 29 September 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Combey, Sylvio (29 October 2018). "Togo : un monument de guerrier criblé de balles à Kparatao". AFRICA RENDEZ VOUS - L'Afrique, par des Africains. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Didier, A. "Togo: A Timbu, le "Chevalier" Faure équipé pour une victoire totale en 2020". Togo Breaking News. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Gouraud (2002, p. 70)

- Rousseau (2014, p. 405)

- Gouraud (2002, p. 63)

- Belei (1991, p. 18)

- "Quand Adébayor devient « notable » à Kpalimé". Actualité du Togo, Information de Lome, Lome Nachrichten. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Belei (1991, p. 12)

- Belei (1991, p. 15)

- Mathis, Andre (1997). "Don't put the cart before the horse!". Spore. ISSN 1011-0054. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Gouraud (2002, p. 61)

- Gouraud (2002, p. 68)

- Gouraud (2002, p. 65)

- Passot, Bernard (1988). Togo : les hommes et leur milieu : guide pratique [Togo: men and their environment: practical guide] (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 208.

- "Découverte du Horse-ball avec Hymane épique club de Lomé". Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Belei (1991, p. 13)

- Belei (1991, p. 17)

- Moshinaly, Houssen. "Pourquoi est-il si difficile d'empêcher les gens de mourir d'une morsure de serpent?" [Why is it so difficult to prevent people from dying from snake bites?]. Actualité Houssenia Writing (in French). Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Law (2018, p. 42)

- Belei (1991, p. 2)

- Belei (1991, p. 19)

- Belei (1991, p. 14)

- Belei (1991, p. 3)

- Belei (1991, p. 4)

- Belei (1991, p. 10)

- Gouraud (2002, p. 71-72)

- Gouraud (2002, p. 71)

- Porter, Valerie; Alderson, Lawrence; Hall, Stephen J. G.; Sponenberg, Dan Phillip (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding (in French) (6th ed.). CAB International. p. 442. ISBN 978-1-84593-466-8.

- Law (2018, p. 25)

- Belei (1991, p. 7)

- Belei (1991, p. 28)

- Journal de physiologie et de pathologie générale (in French). Vol. 7. Masson et Cie. 1905. p. 756.

- Ali-Napo, Pierre (1900–1909). Le Togo, terre d'expérimentation de l'assistance technique internationale de Tuskegee University en Alabama (in French). Éditions Haho. p. 166. ISBN 291374608X.

- Belei (1991, p. 29)

- Belei (1991, p. 30)

- Belei (1991, p. 31)

- Belei (1991, p. 33)

- Belei (1991, p. 68)

- Belei (1991, p. 76)

- Belei (1991, p. 69,77)

- Belei (1991, p. 81)

- Domingo, A. M. (21 July 2000). "Current status of some zoonoses in Togo". Acta Tropica. 76 (1): 65–69. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00092-9. ISSN 0001-706X. PMID 10913769. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Belei (1991, p. 25,26)

- Toulabor, Comi M. (1986). Le Togo sous Eyadéma. Les Afriques (in French). Karthala Éditions. p. 332. ISBN 2865371506.

- Zöller (1990, p. 31)

- Zöller (1990, p. 86)

- Prilop, Gerhard (1985). Contes et mythes du Togo : la marmite miraculeuse (in French). Éditions Haho. pp. 187, 189, 197.

- Contes (1984). "Togo dialogue". Imprimerie Editogo (95–112): 62.

- Gayibor (2011a, p. 219)

Bibliography

- Belei, Donguila (1991). Contribution à la connaissance et la pathologie infectieuse et parasitaire du cheval au Togo (PDF) (in French). Université Cheikh-Anta-Diop.

- Gayibor, Nicoué (2011a). Histoire des Togolais. Des origines aux années 1960. Du XVIe siècle à l'occupation coloniale (in French) (2nd ed.). Karthala Éditions. ISBN 978-2811133436.

- Gayibor, Nicoué (2011b). Histoire des Togolais. Des origines aux années 1960. Le Togo sous administration coloniale (in French) (3rd ed.). Karthala Éditions. ISBN 978-2811133443.

- Gouraud, Jean-Louis (2002). L'Afrique par monts et par chevaux. Tourisme équestre en Afrique ? Go to Togo ! (in French). Éditions Belin. ISBN 2-7011-3418-8.

- Gouraud, Jean-Louis (2017). Petite Géographie amoureuse du cheval. 31. Afrique : Tourisme équestre au Togo (in French). Humensis. ISBN 978-2-410-00205-8.

- Law, Robin (2018). The horse in West African history : the role of the horse in the societies of pre-colonial West Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-95456-6. OCLC 1049149788.

- Rousseau, Élise (2014). Tous les chevaux du monde (in French). Delachaux et Niestlé. ISBN 978-2-603-01865-1.

- Porter, Valerie; Alderson, Lawrence; Hall, Stephen J. G.; Sponenberg, Dan Phillip (2016). Mason's World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding (6th ed.). CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-466-8.

- Zöller, Hugo (1990). Le Togo en 1884. 1 de Chroniques anciennes du Togo (in French). Vol. 1. Translated by Amegan, K.; Ahadji, A. Lomé: Karthala et éditions Haho. ISBN 290671822X.

.jpg.webp)