Human–animal breastfeeding

Human to animal breastfeeding has been practiced in some different cultures during various time periods. The practice of breastfeeding or suckling between humans and other species occurred in both directions: women sometimes breastfed young animals, and animals were used to suckle babies and children. Animals were used as substitute wet nurses for infants, particularly after the rise of syphilis increased the health risks of wet nursing. Goats and donkeys were widely used to feed abandoned babies in foundling hospitals in 18th- and 19th-century Europe. Breastfeeding animals has also been practised, whether for perceived health reasons – such as to toughen the nipples and improve the flow of milk – or for religious and cultural purposes. A wide variety of animals have been used for this purpose, including puppies, kittens, piglets and monkeys.

Breastfeeding by animals of humans

Terracotta feeding bottles surviving from the third millennium BC in Sumeria indicate that children who were not being breastfed were receiving animal milk, probably from cows. It is possible that some infants directly sucked lactating animals,[1] which served as alternatives to wet nurses. Unless another lactating woman was available, a mother who lacked enough breast milk was likely to lose her child. To avert that possibility if a wet nurse was not available, an animal such as a donkey, cow, goat, sheep or dog could be employed. Suckling directly was preferable to milking an animal and giving the milk, as contamination by microbes during the milking process could lead to the infant contracting a deadly diarrheal disease. It was not until as late as the 1870s that stored animal milk became safe to drink due to the invention of pasteurisation and sterilisation.[2]

The Jewish Talmud permits children to suckle animals if the child's welfare dictates it.[3]

Mythology and stories

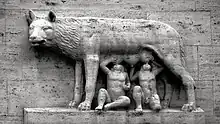

The suckling of infants by animals was a repeated theme in classical mythology. Most famously, twin brothers Romulus and Remus (the former founded Rome) were portrayed as having been raised by a she-wolf which suckled the infants, as depicted in the iconic image of the Capitoline Wolf. The Greek god Zeus was said to have been brought up by Amalthea, portrayed variously as a goat who suckled the god or as a nymph who brought him up on the milk of her goat. Similarly, Telephus, the son of the demigod Heracles, was suckled by a deer.[4] Several famous ancient historical figures were claimed to have been suckled by animals; Cyrus I of Persia was said to have been suckled by a dog, while mares supposedly suckled Croesus, Xerxes and Lysimachus. In reality, though, such stories probably owed more to myth-making about such prominent figures, as they were used as evidence of their future greatness.[5]

A 12th century novel from Al-Andaluz, Hayy ibn Yaqdhan,[6] has the title character growing up in isolation on a tropical island, fed and raised by an antelope. The story reached Europe in a Latin translation, and then in 1708 an English edition.

Stories of abandoned children being brought up by animal mothers such as she-wolves and bears were widespread in Europe from the Middle Ages and into modern times. One real-life case was that of Peter the Wild Boy, found in northern Germany in 1724. His coarse, curly hair was attributed to his being (supposedly) suckled by a bear, based on the premise that characteristics of the animal foster mother had been transmitted to him via her milk.[7] (It is now thought he had Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a condition unidentified until 1978.[8])

Perceived effect on character

The belief that animal characteristics could be transmitted via milk was widely held; the Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus thought that being suckled by lionesses conferred great courage.[7] Goats were thought to transmit a libidinous character and some preferred to employ donkeys as wet nurses instead, as they were thought to be more moral animals.[9] In modern Egypt, though, donkeys were disfavoured as wet nurses as it was thought that a child suckled on donkeys' milk would acquire the animal's stupidity and obstinacy.[10] Human milk was thought to transmit character traits as well; in 19th century France a law was proposed to ban disreputable mothers from nursing their own children so that their immoral traits would not be transmitted via their milk.[5]

Use of goats and other animals

Goats have often been used to suckle human babies and infants. The Khoikhoi of southern Africa were reported to tie their babies to the bellies of female goats so that they could feed there. In the 18th and 19th centuries, goats were widely used in Europe as alternatives to human wet nurses, as they were easier to obtain, cheaper to use and safer, in that they were less prone to passing on diseases.[9] This use of animals was already a well-established practice in rural France and Italy; Pierre Brouzet, the personal physician of Louis XV of France, wrote of how he had seen "some peasants who have no other nurses but ewes, and these peasants were as strong and vigorous as others."[11] In 1816, a German writer named Conrad A. Zweirlein overheard a conversation at a fashionable resort about the problems of wet nurses and responded by writing a book called The Goat as the Best and Most Agreeable Wet Nurse, which popularised the use of the animals for many years.[9] Zwierlein describes how a father living in a German village trained his goat to jump on a table, where he had laid his motherless child on a pillow. The goat would stand waiting until the baby drank its fill of her milk.[12]

One important use of goats for suckling concerned the feeding and attempted cure of babies born with congenital syphilis inherited from their mothers. Liquid compounds laced with mercury were fed to nanny goats – if they refused to drink them, honey was recommended as a way of disguising the metallic taste – or were ingested into the goat's bloodstream via a deliberately inflicted wound on the animal's leg that was covered with an ointment containing mercury. The mercury would accumulate in the goats' milk and was passed into the syphilitic babies when they suckled at the goats' teats. This method did have some effect of improving the infants' mortality rates, though the goats tended to die prematurely of mercury poisoning.[13]

Zwierlein's personal opinion was that women who are sick, dehydrated, depressed, or even in old age should not breastfeed their own babies because their milk could harm the child. He felt that even mothers who did not love their child and would rather spend time in pursuits other than tending to their baby should not breastfeed.[12] In his experience, poor women who were paid to be wet nurses in Germany were most likely to pass venereal disease and other illnesses on to the baby, who, when returned to the care of its parents, passed the disease on to them. Zwierlein insisted that for a human baby in such circumstances, a goat's milk was preferable to a woman's. Goats, he asserted, are clean, tame, playful, friendly, social, good-natured, not easily frightened, and not prone to anger. Zwierlein also spoke of several country towns he knew of where adults and infants used goat's milk exclusively, as it was easier than cow's milk to digest.

In France, homes for foundlings (abandoned babies) often kept large numbers of goats to feed the infants, as they were considered less problematic than lower-class wet nurses. In some institutions, nurses (nannies) carried the infants to the goats; elsewhere, the goats came to the infants. Alphonse Le Roy described how goats were used at the foundling hospital in Aix-en-Provence in 1775: "The cribs are arranged in a large room in 2 ranks. Each goat which comes to feed enters bleating and goes to hunt the infant which has been given it, pushes back the covering with its horns and straddles the crib to give suck to the infant. Since that time they have raised very large numbers [of infants] in that hospital."[11]

In 19th-century Ireland, foundlings from Dublin were "sent to the mountains of Wicklow, to feed upon the goats' milk. As the children grew older, the goats came to know them, and became very tame; so that the infant sought the goat, and was suckled by it as he would have been by a human wet nurse. These children throve remarkably well."[14] Donkeys were preferred in England; as one writer has put it, "nothing was more picturesque than the spectacle of babies, held under the bellies of the donkeys in the stable adjoining the infants' ward, sucking contentedly the teats of the docile donkeys."[9] Ancient Greek and Roman physicians including Galen, Aretaeus, Hipposcrates, and Alexander of Tralles believed that donkey milk was a superior treatment for human illness and an antidote for poisons.[15] In Brittany, attempts were made around 1900 to employ sows as wet nurses but foundered due to opposition to the use of pigs for this purpose.[16]

Breastfeeding by humans of animals

The breastfeeding by humans of animals is a practice that is widely attested historically and continues to be practised today by some cultures. The reasons for this are varied: to feed young animals, to drain a woman's breasts, to promote lactation, to harden the nipples before a baby is born, to prevent conception, and so on.[17]

Simoons and Baldwin gathered and summarized global accounts of human-animal breastfeeding in their 1982 paper entitled, “Breast-Feeding of Animals by Women: Its Social-Cultural Context and Geographic Occurrence.” They studied the motivations of women world-wide for breast-feeding animals and categorized them in four ways: the most common situation in which women nursed animals was the affectionate breastfeeding of family pets. The second most common motivation for this practice was economic; for example, to save an animal who might otherwise die, and could be eaten or be useful to the family economy in some way. Ceremonial breastfeeding of animals was the third category, relating to rituals, sacrifice, cultural or religious customs. Nursing animals for the mother's sake, such as relieving pain from mastitis or engorged breasts, was found to be the least common motivation.[18]

Economic reasons

Bears were also suckled by the Itelmens of the Kamchatka Peninsula of Russia but in their case for economic reasons, to benefit from the meat when the bear was grown and to obtain highly prized bear bile for use in traditional medicine.[17] American animal trafficker Frank Buck claimed that human mothers in remote Indonesian villages would nurse to orangutan babies in hopes of keeping them alive long enough to sell to a wildlife trader.[19]

Religious and ceremonial reasons

Religious and ceremonial reasons have also been a factor. Saint Veronica Giuliani (1660–1727), an Italian nun and mystic, was known for taking a lamb to bed with her and suckling it as a symbol of the Lamb of God.[7] In far northern Japan, the Ainu people are noted for holding an annual bear festival at which a captured bear, raised and suckled by the women, is sacrificed.

For the mother's sake

English and German physicians between the 16th and 18th centuries recommended using puppies to "draw" the mother's breasts, and in 1799 the German Friedrich Benjamin Osiander reported that in Göttingen women suckled young dogs to dislodge nodules from their breasts.[17] An example of the practice being used for health reasons comes from late 18th century England. When the writer Mary Wollstonecraft was dying of puerperal fever following the birth of her second daughter, the doctor ordered that puppies be applied to her breasts to draw off the milk, possibly with the intention of helping her womb to contract to expel the infected placenta that was slowly poisoning her.[20] Mary Cooley Spencer, an American woman living in Colonia Dublan in 1911, breastfed a collie puppy while suffering from smallpox. She had a five month old daughter, who was cared for by a friend while she recovered. Nursing the puppy allowed her to maintain her milk supply until she was no longer contagious.[21]

Animals have widely been used to toughen the nipples and maintain the mother's milk supply. In Persia and Turkey puppies were used for this purpose. The same method was practised in the United States in the early 19th century; William Potts Dewees recommended in 1825 that from the eighth month of pregnancy, expectant mothers should regularly use a puppy to harden the nipples, improve breast secretion and prevent inflammation of the breasts. The practice seems to have fallen out of favour by 1847, as Dewees suggested using a nurse or some other skilled person to carry out this task rather than an animal.[22]

Other or undetermined reasons

Tribal peoples around the world have breastfed many types of animal. Travelers in Guyana observed native women breastfeeding a variety of animals, including monkeys, opossums, pacas, agoutis, peccaries and deer.[17] Native Canadians and Americans often breastfed young dogs; an observer commented that the Pima people of Arizona "withdrew their breasts sooner from their own infants than from young dogs."[23] According to Sir John Richardson, eighteenth Century Native Americans reportedly fed human breast milk to bison calves, wolves and bears.[24] In 1875, a British surgeon named John Nisbet reportedly observed a group of Burmese women breastfeeding a royal white elephant in the Konbaung court.

In the late 16th Century, Konrad Heresbach recommended that mothers rid their bodies of their first milk, called colostrum, rather than allow their babies to drink it.[15] The idea that colostrum was dangerous for a newborn further took hold in Europe when Thomas Newton wrote of its supposed dangers.[25] How widely this idea was accepted is impossible to know, but it could have been an additional purpose for human-animal breastfeeding as women sought a means to discard colostrum while establishing a milk supply for their baby.

Artistic and political statements

In the present day, the act of breastfeeding animals has been used as a sometimes controversial artistic statement. The album art for Boys for Pele by Tori Amos includes a photograph of the singer breastfeeding a piglet.[26] In Ireland, 22-year-old model and PETA member Agata Dembiecka became the focus of controversy in 2010 when a calendar issued by an animal rescue charity featured a photograph of her suckling a puppy.[27]

Notes

- Van Esterik 1995, p. 147.

- Ensminger 1995, p. 572.

- Radbill 1976, p. 23.

- Savona-Ventura 2004, p. 16.

- Radbill 1976, p. 22.

- Kukkonen, Taneli (November 2016). "Ibn Ṭufayl's (d. 1185) Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓan". In El-Rouayheb, Khaled; Schmidtke, Sabine (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Philosophy. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199917389.013.35. ISBN 978-0-19-991738-9. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Schiebinger 1993, p. 56.

- Kennedy & 20 March 2011.

- Radbill 1976, p. 24.

- Omm Sety 2008, p. 2.

- Valenze 2011, p. 159.

- Zwierlein, Konrad Anton. Die Ziege als beste und wohlfeilste Säugamme.

- Burton 2007, pp. 108–9.

- Routh 1860, p. 156.

- Jackson, Melanie. Deeper in the Pyramid.

- Radbill 1976, p. 25.

- Radbill 1976, p. 26.

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1982). "Breast-feeding of animals by women: its sociocultural context and geographic occurrence". Anthropoid: 435.

- Buck, Frank (2000). Bring 'em back alive : the best of Frank Buck. Steven Lehrer. Lubbock, Tex.: Texas Tech University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-89672-430-1. OCLC 43207125.

- Tomalin 2004, pp. 280–1.

- "Mary Cooley". www.familysearch.org. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- Radbill 1976, p. 2–7.

- Radbill 1976, p. 27.

- Serpell, James (2008). In the Company of Animals: A Study of Human-Animal Relationships. Cambridge University Press.

- Radbill, Samuel X. American Folk Medicine : A symposium, "The role of animals in infant feeding".

- Farley & 11 May 1998.

- Belfast Telegraph & 30 December 2010.

References

- Burton, June K. (2007). Napoleon and the Woman Question. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 9780896725591.

- Ensminger, Audrey H. (1995). Concise Encyclopedia of Foods and Nutrition. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849344558.

- Farley, Christopher John (11 May 1998). "Tori, Tori, Tori!". TIME. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008.

- Kennedy, Maev (20 March 2011). "Peter the Wild Boy's condition revealed 200 years after his death". The Guardian.

- Omm Sety (2008). Omm Sety's Living Egypt: Surviving Folkways from Pharaonic Times. Glyphdoctors. ISBN 9780979202308.

- Radbill, Samuel X. (1976). "The Role of Animals in Infant Feeding". In Hand, Wayland D (ed.). American Folk Medicine: A Symposium. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520040939.

- Routh, Charles Henry F. (1860). Infant feeding and its influence on life: or, The causes and prevention of infant mortality. John Churchill.

- Savona-Ventura, C. (2004). Breast versus Bottle. A history of Infant feeding in Malta. Association for the Study of Maltese Medical History. ISBN 99932-663-1-0.

- Schiebinger, Londa L. (1993). Nature's Body: Gender In The Making Of Modern Science. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813535319.

- Tomalin, Claire (2004). The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141912264.

- Valenze, Deborah (2011). Milk: A Local and Global History. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300117240.

- Van Esterik, Penny (1995). "The Politics of Breastfeeding". In Stuart-Macadam, Patricia; Dettwyler, Katherine Ann (eds.). Breastfeeding: Biocultural Perspectives. Aldine. ISBN 9780202011929.

- "Model breastfeeding a puppy calendar has dog lovers feeling hot under collar". Belfast Telegraph. 30 December 2010.