Hume Castle

Hume Castle is the heavily modified remnants of a late 12th- or early 13th-century castle of enceinte held by the powerful Hume or Home family, Wardens of the Eastern March who became successively the Lords Home and the Earls of Home. The village of Hume is located between Greenlaw and Kelso, two miles north of the village of Stichill, in Berwickshire, Scotland. (OS ref.- NT704413). It is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, recorded as such by Historic Environment Scotland.[1]

| Hume Castle | |

|---|---|

Middle English: Home Castle | |

| Hume, Berwickshire, Scotland | |

| |

Hume Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55°39′55″N 2°28′15″W |

| Type | Castle of enceinte, recreated as a folly |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Clan Home Association / Historic Scotland |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined, rebuilt as folly |

| Site history | |

| Built | 12th/13th century |

| Built by | William de Home |

| Materials | Stone |

| Demolished | 1650 |

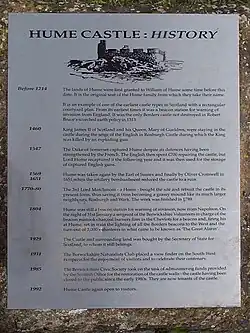

Standing as it does, on an impressive height above its eponymous castleton, it commands fine prospects across the Merse, with views to the English border at Carter Bar. It had historically been used as a beacon to warn of invasion. Its enormous walls were created in the 18th century but remnants of the central keep and other features can still be seen.

History

Origins

William de Home, son of Sir Patrick de Greenlaw (a younger son of Cospatric I, Earl of Dunbar), acquired the lands of Home in the early 13th century through marriage to his cousin Ada (the daughter of Patrick I, Earl of Dunbar). He then took his surname from his estate, a not uncommon practice of the time. It is assumed that he built the first stone fortifications at the site.

James II stayed at Home en route to the siege of Roxburgh Castle, the last English garrison left in Scotland following the Wars of Independence. (James was killed by the explosion of an early bombard during the siege.)

Sixteenth century and the Rough Wooing

In August 1515 Regent Albany imprisoned members of the Hume family at Dunfermline, with Adam Tinmo, the Constable of Hume Castle. At this time, Scotland's Governor Regent Albany was planning to bring an army against the Hume family on the Scottish borders. Albany captured Hume Castle, but according to a report by Cardinal Wolsey's chaplain, William Frankelayn, Chancellor of Durham, Lord Hume, Lord Chamberlain, retook the castle on 26 August 1515, and kept Albany's captain, Lord Fleming's uncle, prisoner. Lord Hume then slighted his own castle, razed the walls, "and dammed the well for ever more."[2]

Before the advent of artillery, Hume castle was considered almost impregnable. However it was captured in 1547 during the "Rough Wooing", by the Lord Protector Somerset. The Scottish ruler, Regent Arran, had sent 12 gunners to defend the castle in August 1547.[3] George Home, 4th Lord Home, was injured at the Battle of Pinkie and his son Alexander captured. After stout resistance by Mariotta (or Marion) Haliburton, Lady Home, the castle fell and an English garrison was installed. According to an English account, the castle was rendered by the negotiation of Lady Home after the English army encamped nearby at the Hirsel or Hare Craig. Although English artillery was placed to commence bombardment, no shot was fired by either side. Somerset Herald conveyed Lady Home's instructions to the reluctant garrison who would have preferred Lord Home's word as a warrant for their surrender.[4]

Baron Dudley holds the castle for England

Sir Edward Sutton, a cousin of the Earl of Warwick, was made Captain of Hume, and received the keys from Andrew Home, Commendator of Jedburgh and Restennet, on Thursday 22 September 1547. There were seventy-eight Scots within, and Edward Sutton found guns including; 2 batard culverins; a saker; 3 brass falconets; and eight other iron guns.[4] More guns were brought to hold the castle, and an English inventory of December 1547 lists 21 cannons including 4 fowlers, and 40 hand-guns.[5] Minor strengthening work was carried out by the English, on the advice of the military engineer William Ridgeway, but only £734 was spent, the local stone was unsuitable and limestone at Roxburgh too far away.[6]

Mariotta, Lady Home, complained to the Duke of Somerset on 2 November 1547 that she had, "been very sore examined for the rendering of Hume", and accused of taking money. She thought it marvellous that anyone could think she could keep the "sober barmkin" of Hume against the English army, when all the nobles of Scotland could not keep the field.[7] Hume Castle was nearly lost in February 1548, when Captain Pelham travelled to Warkworth Castle to collect pay for the Spanish mercenary garrison. The soldiers planned to rob him and change sides. Loyal members of the garrison fired the beacon and Sir John Ellerker's men arrested the would-be deserters. One was killed escaping, and Grey of Wilton planned to hang six of them, but the two leaders escaped into Scotland.[8]

Lord Home recaptures the castle

After the death of his father, captive in the Tower of London, the young Alexander, 5th Lord Home, with the help of his brother Andrew the Commendator, recaptured the castle in December 1548. The first man in was Tulloch, a servant of the laird of Buccleuch.[9] Edward Sutton was blamed for losing the castle by negligence to a night assault. Jean de Beaugué, a French soldier gave an account of the re-capture. He said that an inside-man let in seven Scots, and at night an eighth man climbed in. These then overwhelmed the garrison. In Jean's account the man who climbed the wall was a Home, aged 60.[10] Sutton was taken to Spynie Palace,[11] and was still a prisoner at the end of the war, when the Earl of Shrewsbury was asked to organise his release by the exchange of French hostages.[12]

Mariotta, Lady Home, sent the news to Mary of Guise on 28 December 1548 from Edinburgh. Regent Arran thanked John Hume of Cowdenknowes for his service recovering the castle. The English unsuccessfully attempted to recapture Hume in February 1549.[13] Lady Home was once again installed in the castle in March 1549 and complained to Mary of Guise in March 1549 of the behaviour of the French and Spanish garrison obtaining credit from the villagers.[14] When the English abandoned their fort at Lauder the guns there were dragged by oxen to Hume Castle.[15]

Mary of Guise ordered the people of Sherriffdom of Berwick and Lauderdale to provide 320 oxen to remove the guns from Hume in February 1558. The cannons were taken to the fort at Eyemouth.[16] The castle was again besieged in April 1570, during the Marian Civil War, by the Earl of Sussex during his raid into Scotland. The defenders capitulated within twelve hours, in awe of his superior numbers and the firepower of "three battery pieces and two sakers" brought from Wark Castle.[17] Regent Morton gave money to Agnes Gray, Lady Home, in the 1570s to keep the castle garrisoned for James VI.[18]

Downfall

The 17th century saw the demise of Hume Castle as a habitable fortress. The Earls of Home had already established another seat at Dunglass Castle and, by 1611, at The Hirsel. Hume Castle finally succumbed to the forces of Cromwell in 1650 during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. James, 3rd Earl of Home was a prominent member of the Kirk Party. After Cromwell's successful investiture of Edinburgh Castle, he sent Colonel George Fenwick with two regiments to besiege the Earl's Castle. Catherine Morrison, Lady Wedderburn, paid £6 to bring cannon to defend Hume.[19] The governor of the castle, Colonel John Cockburn,[20] engaged in witty repartee with the Roundheads, but refused to deliver the castle. He claimed that he had no idea who Cromwell was and that the castle stood on a rock. He sent a note to Fenwick with the following doggerel:

- "I, Will of the Wastle

- Am King of my castle

- All the dogs in the town

- Shall gare gang me down!"[21]

However once the bombardment began, it became clear that there was no option but submission. Fenwick's troops entered the castle, and accepted Cockburn's surrender. Cockburn and his men were given quarter for life only. They retreated and Fenwick slighted the fortification.[22]

Resurrection

In the early 18th century, Hume and its environs came into the possession of the Earls of Marchmont, wealthier and more influential cadets of the main line of the family. The Castle at this point was level with the ground that it was built upon. At some point before his death in 1794, Hugh Hume-Campbell, 3rd Earl of Marchmont, 3rd Lord Polwarth, restored the castle as a folly, from the waste left from its destruction, on the original foundations of its curtain wall. He adorned the wall tops with enormous crenellations that are more picturesque than practical.

The Great Alarm

In light of its function as a mediæval early warning system, the castle was used again as a beacon during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1804, on the night of 31 January, a sergeant of the Berwickshire Volunteers in charge of the beacon mistook charcoal burners' fires on nearby Dirrington Great Law for a warning. Lighting the beacon at Hume Castle, he set in train the lighting of all the Borders beacons to the West, and 3,000 volunteers turned out in what became known as 'The Great Alarm'.[21]

Again, during the Second World War it functioned as a lookout post, and was also to act as a base for resistance in the event of a German invasion.

Today

The castle is still seen as the spiritual home of the many Homes and Humes in Scotland and abroad. The castle was bought by the state in 1929, and in 1985 a restoration programme was undertaken by the Berwickshire Civic Society funded by the Scottish Office. It re-opened to the public in 1992. In 2006 the Civic Society handed over the castle to a charitable trust run by the Clan Home Association, under the auspices of Historic Scotland, to maintain its preservation in the future.[23]

References

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Hume Castle, castle and associated settlement (SM387)". Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Letters & Papers of Henry VIII, vol. 2 (London, 1864), no. 861.

- Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1911), 100.

- Patten, William, The Expedition into Scotland, 1547 (London, 1548): A. F. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (Constable, 1903), pp. 142-145.

- David Starkey, The Inventory of Henry VIII, vol. 1 (Society of Antiquaries, 1998), p. 143.

- Howard Colvin, The History of the King's Works, vol. 4 part 2 (HMSO, 1982), 699, 706, citing PRO SP15/2 f.81, SP10/15/11.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1898), p. 36 no. 75.

- Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (1898), 76-7, 101: Calendar of State Papers Spain, vol. 9 (London, 1912), 260.

- Annie Cameron, Scottish Correspondence of Mary of Lorraine (Edinburgh, 1927), pp. 280-281, 283, 288, Tulloch was killed while firing the gate of Ferniehirst Castle in February 1549.

- Jean de Beaugué, History of the Campaigns of 1548 and 1549 (Edinburgh, 1707), pp. 77-82.

- HMC Longleat: Seymour Papers, IV (London, 1968), p. 109.

- John Roche Dasent, Acts of the Privy Council, vol. 2 (London: HMSO, 1890), p. 421.

- Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1911), 264, 285.

- Annie I. Cameron, Scottish Correspondence of Mary of Lorraine (SHS, 1927), pp. 280-281, 283, 296-297.

- Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 9 (Edinburgh, 1911), pp. 421, 423.

- Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1913), pp. lxxi, 333-334.

- Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. 3 (London, 1791), p. 43.

- HMC 12th report appendix part VIII, Earl of Home (London, 1891), p. 100.

- HMC Home of Wedderburn (London, 1902), p. 102.

- Cockburn, Sir Robert, and Harry A. Cockburn, The Records of the Cockburn Family(London: T. N. Foulis, 1913).

- "Castle History". Hume Castle Preservation Trust. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Hume Castle (58561)". Canmore. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "Welcome to the Hume Castle Preservation Trust". Hume Castle Preservation Trust. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

Sources

- Ordnance Gazetteer-Scotland Vol IV,ed. F.H. Groome, Edinburgh, 1883