Ikaria wariootia

Ikaria wariootia is an early example of a wormlike, 2–7 mm-long (0.1–0.3 in) bilaterian organism. Its fossils are found in rocks of the Ediacara Member of South Australia that are estimated to be between 560 and 555 million years old.[1] A representative of the Ediacaran biota, Ikaria lived during the Ediacaran period, roughly 15 million years before the Cambrian, when the Cambrian explosion occurred and where widespread fossil evidence of modern bilaterian taxa appear in the fossil record.[1][2][3]

| Ikaria wariootia Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

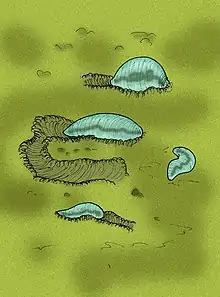

| Artist's restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Genus: | †Ikaria Evans et al, 2020 |

| Species: | †I. wariootia |

| Binomial name | |

| †Ikaria wariootia Evans et al, 2020 | |

Discovery

Scott D. Evans, Ian V. Hughes, James G. Gehling, and Mary L. Droser published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America on 23 March 2020, describing the finding and identification of I. wariootia.[1]

Age

The age of Ediacara Member strata are not well-defined through radiometric dating, and are primarily estimated comparatively with other Ediacaran Biota assemblages, likely ranging between approximately 562 Ma and 542 Ma.[4] Brazilian trace fossils associated with later bilaterians, found 30-40m above a bed radiometrically dated to 555 Ma, are thought to be younger than Ikaria.[1] It is possible that Ikaria evolved prior to 560 Ma.[1]

Etymology

The generic name is taken from the Adnyamathanha word for "meeting place" (Ikara, also the name for nearby Wilpena Pound) in recognition of the local indigenous people who originally lived in the region where the fossils were collected. The specific name refers to Warioota Creek, the type locality.[1]

Features

Over 100 Ikaria fossils have been found.[2] These are simple imprints resembling a small grain of rice (from 1.9 to 6.7 mm in length), slightly thickening to one end. The "anterior"/"posterior" differentiation may indicate that Ikaria was a bilaterally symmetrical animal. No other details of Ikaria anatomy were found on its fossils.[1]

On the same sandstone bed there are numerous trace fossils of the type Helminthoidichnites. The animal that produced such traces moved or burrowed through thin layers of well-oxygenated sand on the ocean floor[3] as it sought sustenance and appeared to show sensory and seeking behaviour, turning as it moved. It is thought to have moved by peristalsis, constricting muscles against the animal's hydrostatic skeleton, and may have possessed a coelom, mouth, anus, and through-gut, in a similar way to a worm.[1]

The authors of the Ikaria description find that the size and morphology of Ikaria match predictions for the producer of the trace fossil Helminthoidichnites.[2][3][1] At least one of the fossils of Ikaria identified in the study was found in close proximity to Helminthoidichnites, which the discoverers attribute to vertical motion of the organism through sediment before its death - noting that due to differing preservation methods it is unlikely that both trace and body fossil could otherwise form simultaneously.[1] However, this does not entirely remove the possibility that the association of Ikaria with Helminthoidichnites is erroneous.

Significance

This discovery is notable because while it has been long suspected that bilaterians evolved in the Ediacaran, for example Temnoxa and Kimberella, yet the vast majority of Ediacaran biota fossils are very different from the animals that came to dominate the life on Earth in the Cambrian and until present day.

References

- Evans, Scott D.; Hughes, Ian V.; Gehling, James G.; Droser, Mary L. (23 March 2020). "Discovery of the oldest bilaterian from the Ediacaran of South Australia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (14): 7845–7850. doi:10.1073/pnas.2001045117. PMC 7149385. PMID 32205432.

- Davis, Nicola (23 March 2020). "Fossil hunters find evidence of 555m-year-old human relative". The Guardian.

- "Ancestor of all animals identified in Australian fossils". Phys.org. 23 March 2020.

- Grazhdankin, Dima (8 February 2016). "Patterns of distribution in the Ediacaran biotas: Facies versus biogeography and evolution". Paleobiology. Cambridge University Press. 30 (2): 203–221. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0203:PODITE>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 129376371.