Illusion of Kate Moss

The illusion of Kate Moss is an art piece first shown at the conclusion of the Alexander McQueen runway show The Widows of Culloden (Autumn/Winter 2006). It consists of a short film of English model Kate Moss dancing slowly while wearing a long, billowing gown of white chiffon, projected life-size within a glass pyramid in the centre of the show's catwalk. Although sometimes referred to as a hologram, the illusion was made using a 19th-century theatre technique called Pepper's ghost.

McQueen conceived the illusion as a gesture of support for Moss; she was a close friend of his and was embroiled in a drug-related scandal at the time of the Widows show. It is regarded by many critics as the highlight of the Widows runway show, and it has been the subject of a great deal of academic analysis, particularly as a wedding dress and as a memento mori. The illusion appeared in both versions of Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, a retrospective exhibition of McQueen's designs.

Background

British designer Alexander McQueen was known in the fashion industry for dramatic, theatrical fashion shows featuring imaginative, sometimes controversial designs.[1] He was a close friend of English model Kate Moss, who had walked in several of his previous shows, including La Poupée (Spring/Summer 1997) and Voss (Spring/Summer 2001).[2][3][4] Moss retired from runway modelling in 2004 to focus on advertising contracts and other ventures.[5][6] In 2005, she became caught up in controversy after images of her allegedly using drugs were leaked to the media, and several companies cancelled lucrative contracts with her.[7][8]

McQueen actively supported Moss throughout the controversy. He argued that in his opinion, many journalists also regularly used drugs, making their criticism hypocritical.[9][10] He wore a T-shirt with the words "We love you Kate!" when he appeared at the end of the runway show for Neptune (Spring/Summer 2006).[11][12] As a further gesture of support, he developed the idea of projecting her into the closing act of upcoming show, The Widows of Culloden (Autumn/Winter 2006), seeking "to show that she was more ethereal, bigger than the situation she was in".[13][14][2]

Illusion

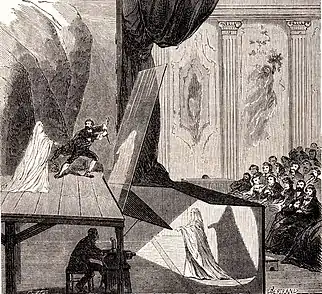

The illusion played as the finale of the runway show for The Widows of Culloden on 3 March 2006 at the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy.[15][16] The stage was formed by a square of rough wood with a large glass pyramid in its centre, leaving a catwalk around the outside for the models to walk.[17][18] After the final model exited the runway, the lights were dimmed and the illusion was projected within the central pyramid.[15] The illusion, sometimes inaccurately described as a hologram, used a 19th-century theatre technique called Pepper's ghost to display a life-sized projection of Kate Moss wearing a billowing chiffon dress.[14][15] In the Pepper's ghost technique, a brightly lit figure out of sight of the audience is partially reflected on an angled pane of glass, which makes the semi-transparent figure appear to be on the stage.[19]

The illusion was executed as a collaboration between British film director Baillie Walsh, production designer Joseph Bennett, post-production company Glassworks, and production duo Gainsbury & Whiting.[20][21][22] Glassworks planned the illusion by creating a computer-generated render of the entire show space, including the seating and the runway. This enabled them to visualise the illusion from multiple viewpoints to confirm that it would look correct no matter where it was viewed from.[23] The performance for Widows was inspired in part by serpentine dance, a type of stage performance from the 1890s that utilised billowing fabric and dramatic lighting, created by dancer Loie Fuller.[24][25]

Filming the effect was difficult, went over budget[9] and took two hours. Moss was suspended in a harness and wind machines were used to create the movement of her dress.[9] The flowing material made it difficult for the production designers to conceal the edges of the illusion. Because the pyramid was visible to the audience from all angles, it was more challenging to execute than an illusion using only a single field of view.[23][26] It was the first fashion show to employ this kind of effect;[27] media theorist Jenna Ng speculated that it may have been the first such large-scale 3D projection of a performance.[26]

Reception and legacy

The illusion of Kate Moss is regarded by many critics as the highlight of the Widows runway show.[28][29] Writing for Vogue, Sarah Mower said that "only Alexander McQueen could provide the astonishing feat of techno-magic that ended his show".[21] Robert McCaffrey, writing in The Fashion Studies Journal, called it "one of McQueen's most enduring and iconic finales".[17] American fashion editor Robin Givhan wrote that "McQueen created a fantasy that made his audience believe in the wizardry of fashion and its ability to move the spirit."[30] Jess Cartner-Morley of The Guardian called it a "suitably haunting finale".[31] Lisa Armstrong at The Times was more critical, calling it "unspeakably cheesy".[32] Kerry Youmans, a publicist for McQueen, recalled seeing audience members crying upon viewing it.[10][33] Writing after McQueen's death in 2010, Lorraine Candy, editor-in-chief of Elle, said that "The hologram of Moss ... was all we talked about for months afterwards."[34] In 2014, Jessica Andrews of Vanity Fair named it one of the most dramatic runway stunts in history.[35]

The Victoria and Albert Museum (the V&A) in London owns a variant of the Kate Moss dress created by McQueen's assistant Sarah Burton for the 2006 wedding of another McQueen employee.[36] Moss wore the original again on the cover of the May 2011 issue of Harper's Bazaar UK.[37] In 2015, the Spanish 15-M movement staged a massive protest via hologram projection, taking specific inspiration from the Kate Moss illusion.[38][39][40]

The Kate Moss illusion appeared in Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, a retrospective exhibition of McQueen's designs shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2011 (the Met) and the V&A in 2015.[41][42][43] In the original presentation at the Met, the Moss illusion was recreated in miniature, but in the V&A re-staging, it was presented in full size in its own room.[lower-alpha 1][24][45] According to Sam Gainsbury, who worked on production for the illusion, McQueen had "always wanted to show [the illusion] independently as a work of art", so the team ensured that it was staged that way for the V&A's version of the exhibit.[46]

Analysis

Gothic tropes

Critics have described The Widows of Culloden as an exploration of Gothic literary tropes – particularly melancholy and haunting – via fashion, and the illusion of Kate Moss plays a significant role in this analysis.[17][47] According to McQueen, the collection took inspiration from Shakespeare's Scottish play Macbeth.[48] Cartner-Morley argued that Moss effectively played the role of Banquo, a character who haunts Macbeth as a ghost throughout the play.[31] Literature professor Catherine Spooner connected the illusion to the visual effects used to portray spirits in the séances of the 19th century, and literary scholar Bill Sherman compared the effect on the audience to the "reverie" inspired by ghost stories of the era.[49][50] Researcher Kate Bethune wrote that the collection's sense of melancholy was "consolidated in its memorable finale".[15]

McCaffrey presented a similar analysis, writing that the illusion of Kate Moss was an example of highly staged Gothic melancholy, playing on the "tensions between beauty and heartache".[17] He contrasted the illusion with the "spine" corset featured in Untitled (Spring/Summer 1998), viewing both as memento mori – artistic reminders of the inevitability of death. He saw the corset as an example of overt material horror, whereas the illusion functioned as an aesthetic horror that depended on the audience's emotional involvement for effect.[17]

McCaffrey called Moss's appearance in the show a kind of resurrection following the damage done to her career by the drug allegations, which may have been a deliberate allusion: after McQueen's death, Moss recalled that when he suggested the concept to her, he said he wanted her to be "rising like a phoenix from a fire".[10][17] Film theorist Su-Anne Yeo argued that the illusion was successful in helping to rehabilitate Moss's image. She wrote that the presentation of the illusion at the V&A particularly "helped to transform Moss from an object of tabloid fodder to one of legitimate critical concern".[14] In a 2014 interview with British photographer Nick Knight, Moss confirmed that she had decided not to attend the show in person, even in disguise; she assumed it would be found out eventually and would "take away from all the magic ... the whole thing of me being a ghost".[51]

Sarah Heaton, whose work focuses on the intersection between fashion and literature, described the illusion as evoking the Gothic trope of the barefoot "mad woman"; normally this figure would be confined to an attic or asylum, but McQueen subverts the expectation by displaying her to the public, making her ephemeral and uncontained.[52] Fashion theorists Paul Jobling, Philippa Nesbitt, and Angelene Wong concur, arguing that the presentation demonstrated that Moss's body, as a symbol of female power, was "numinous, untouchable, and evading capture".[53]

Moss's chiffon gown has been critiqued as an unconventional wedding dress.[54] Cultural theorist Monika Seidl was critical of the illusion, arguing that it presented Moss as a contained female "Wiedergänger" or vengeful spirit.[55] She did however find the dress persuasive in the way it "destabilise[s] the notion of a bride".[55] Literary theorist Monica Germanà also took the dress to be a wedding gown, and found it an example of "the morbid coalescence of love and death", a recurring theme for McQueen.[56]

Technical analysis

Other authors have analysed the illusion of Kate Moss as a form of technologically altered reality, sometimes with supernatural associations. Anthropologist Brian Moeran used the illusion as an example of the runway show as a modern magical ritual, writing that the show's "magic is intimately entwined with technological sophistication".[57] American author Genevieve Valentine described it as a clear science fiction element.[58] Fashion historian Ingrid Loschek wrote that "the catwalk was transformed into a form of virtual reality" through the projection, which energised the audience.[29] Fashion writer Nathalie Khan contrasted the illusion with a straightforward film projection, saying that unlike a film, the illusion made Moss "no longer a mortal subject, but perception made invisible".[27] Jenna Ng described the projection of Moss, a living person, as a kind of rearrangement of physical distance: "the holographic subject appears to be virtually here amongst the present audience even as they are actually elsewhere at the time".[26] She called it an example of the "post-screen", in which there is no barrier between the audience's space and the image.[26]

Yeo was critical of the V&A's emphasis on the technological aspect of the illusion, arguing that it incorrectly positioned the effect as modern rather than historical. She argued that it would have been more appropriate to emphasise the connection to older forms of performance like the serpentine dance and phantasmagoria, a theatrical form that uses magic lanterns.[59] Performance theorist Johannes Birringer was critical of the entire Savage Beauty exhibit, but particularly so of the apparent reverence given to the illusion by the audience: "There was a hushed silence in that holographic room which I found pathetic."[44]

Notes

- In a review of the exhibition, media theorist Johannes Birringer refers to the hologram as "scaled down, in a small dark room", but other sources state that it was full-size compared to the miniature version presented at the Metropolitan Museum.[44]

References

- Vaidyanathan, Rajini (12 February 2010). "Six ways Alexander McQueen changed fashion". BBC Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Knox 2010, p. 12.

- Hyl, Véronique (16 April 2015). "Watch McQueen's '90s Shows in Their Entirety". The Cut. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Maroun, Daniela (18 March 2019). "Fashion: Memories of McQueen". The Journal Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- Vernon, Polly (14 May 2006). "The fall and rise of Kate Moss". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- Cartner-Morley, Jess. "Kate Moss smokes on the catwalk and steals the show at Louis Vuitton". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- Britt, Chantal (20 September 2005). "Kate Moss Ads Scrapped by H&M After Cocaine Pictures". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- "Moss doubles her money after 'Cocaine Kate' scandal". London Evening Standard. London. 14 June 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- Socha, Miles (3 April 2006). "The Real McQueen". Women's Wear Daily. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- Wilson 2015, pp. 299–300.

- Morton, Camilla (7 October 2005). "Alexander McQueen Ready-To-Wear – Catwalk report – Paris Spring/Summer 2006". Vogue. UK. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Wilson 2015, p. 351.

- Watt 2012, p. 228.

- Yeo 2020, p. 149.

- Bethune, Kate (2015). "Encyclopedia of Collections: The Widows of Culloden". The Museum of Savage Beauty. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- Fox 2012, p. 116.

- McCaffrey 2020.

- Young & Martin 2017, pp. 143–144.

- Beech 2011, p. 59.

- Yeo 2020, p. 137.

- Mower, Sarah (2 March 2006). "Alexander McQueen Fall 2006 ready-to-wear collection". Vogue. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Woo, Kin (11 March 2015). "Gainsbury & Whiting on Alexander McQueen". AnOther. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- Williams, Eliza (13 March 2015). "How we made Alexander McQueen's Kate Moss Hologram". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- Yeo 2020, p. 139.

- Albright 2007, p. 2.

- Ng 2021, pp. 174–175.

- Khan 2013, p. 267.

- Gleason 2012, p. 147.

- Loschek 2009, p. 81.

- Givhan, Robin (7 March 2006). "Beware Red Ink On the Runway". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- Cartner-Morley, Jess (4 March 2006). "McQueen's modern Macbeth". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Armstrong, Lisa (4 March 2006). "Is it big or skinny? The answer is both; Paris Fashion Week". The Times. p. 29. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- Sischy, Ingrid (10 March 2010). "A Man of Darkness and Dreams". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- Gleason 2012, p. 152.

- Andrews, Jessica C. (23 September 2014). "The Most Dramatic Fashion-Show Stunts of All Time". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "Widows of Culloden – Alexander McQueen". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 26 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Cowles, Charlotte (30 March 2011). "Kate Moss Wears Two Alexander McQueen Dresses for Harper's Bazaar U.K.'s 'Fashion Royalty' Issue". The Cut. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- Ng 2021, pp. 181–182.

- Sheean 2018, p. 469.

- Córdoba, Carlos (14 April 2015). "Activists mount hologram protest against Spain's 'gag' law". El País (English ed.). Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- "Widows of Culloden". Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- Alexander, Hilary (2 May 2011). "Alexander McQueen's 'Savage Beauty' honoured in style". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Tegan 2021, p. 95.

- Birringer 2016, p. 27.

- Hyland, Véronique (9 October 2014). "Alexander McQueen's Kate Moss Hologram Is Being Revived". The Cut. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- Woo, Kin (11 March 2015). "Gainsbury & Whiting on Alexander McQueen". AnOther. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- Spooner, Catherine (11 March 2015a). "The gothic vision at the heart of Alexander McQueen's savage beauty". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Foley, Bridget (16 May 2006). "Wild Flowers". Women's Wear Daily. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Spooner 2015, p. 143.

- Sherman 2015, p. 243.

- Subjective: Kate Moss interviewed by Nick Knight about Alexander McQueen A/W 2006. SHOWstudio. 24 September 2014. Event occurs at 5:10–5:45. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- Heaton 2017, pp. 95–96.

- Jobling, Nesbitt & Wong 2022, p. 27.

- Heaton 2017, pp. 84, 95–96.

- Seidl 2009, p. 221.

- Germanà 2020, pp. 167–168.

- Moeran 2016, pp. 128–129.

- Valentine 2019, pp. 218–219.

- Yeo 2020, p. 150.

Bibliography

Books

- Albright, Ann Cooper (2007). Traces of Light: Absence and Presence in the Work of Loïe Fuller. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6843-4. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Beech, Martin (2011). The Physics of Invisibility: A Story of Light and Deception. New York City: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4614-0616-7.

- Fox, Chloe (2012). Vogue on: Alexander McQueen. Vogue on Designers. London: Quadrille Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84949-113-6. OCLC 828766756. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Germanà, Monica (2020). Bond Girls: Body, Fashion and Gender. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. ISBN 978-0-85785-643-2. OCLC 1115002952.

- Gleason, Katherine (2012). Alexander McQueen: Evolution. New York City: Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61058-837-9. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Heaton, Sarah (2017). "Wayward Wedding Dresses". In Whitehead, Julia; Petrov, Gudrun D. (eds.). Fashioning Horror. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. pp. 83–100. doi:10.5040/9781350036215.ch-004. ISBN 978-1-350-03621-5. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- Jobling, Paul; Nesbitt, Philippa; Wong, Angelene (2022). Fashion, Identity, Image. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. ISBN 978-1-350-18323-0. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- Khan, Nathalie (4 December 2013). "Fashion as Mythology: Considering the Legacy of Alexander McQueen". In Bruzzi, Stella; Gibson, Pamela Church (eds.). Fashion Cultures Revisited. London: Routledge. pp. 261–271. ISBN 978-0-415-68005-9.

- Knox, Kristin (2010). Alexander McQueen: Genius of a Generation. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-3223-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Loschek, Ingrid (2009). When Clothes Become Fashion: Design and Innovation Systems. Oxford: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85785-144-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Moeran, Brian (2016). The Magic of Fashion: Ritual, Commodity, Glamour. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-41796-7. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Ng, Jenna (2021). "Holograms/Holographic Projections". Holograms/Holographic Projections: Ghosts Amongst the Living; Ghosts of the Living. pp. 155–188. doi:10.2307/j.ctv23985t6.8. JSTOR j.ctv23985t6.8. S2CID 244720894. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Seidl, Monika (2009). "British Fashion and Romanticism Today: Where the Present Dreams the Past Future". In Eckstein, Lars (ed.). Romanticism Today: Selected Papers from the Tübingen Conference of the German Society for English Romanticism. Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier. pp. 215–226. ISBN 978-3-86821-147-4. OCLC 427321505. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Valentine, Genevieve (2019). "Savage Beauty: Alexander McQueen". In Boskovich, Desirina (ed.). Lost Transmissions: The Secret History of Science Fiction and Fantasy. New York City: Abrams Image. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-1-68335-498-7. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Watt, Judith (2012). Alexander McQueen: The Life and the Legacy. New York City: Harper Design. ISBN 978-1-84796-085-6. OCLC 892706946.

- Wilcox, Claire, ed. (2015). Alexander McQueen. New York City: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-1-4197-1723-9. OCLC 891618596.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)- Sherman, Bill. "Ghosts". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 243–246.

- Spooner, Catherine. "A Gothic Mind". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 141–158.

- Wilson, Andrew (2015). Alexander McQueen: Blood Beneath the Skin. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-7674-3.

- Yeo, Su-Anne (2020). "Summoning the Ghosts of Early Cinema and Victorian Entertainment: Kate Moss and Savage Beauty at the Victoria and Albert Museum". In Menotti, Gabriel; Crisp, Virginia (eds.). Practices of Projection: Histories and Technologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-093411-8. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Young, Caroline; Martin, Ann (2017). Tartan + Tweed. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 978-0-7112-3822-0. OCLC 947020251.

Journals

- Birringer, Johannes (2016). "Performance In the Cabinet of Curiosities: Or, The Boy Who Lived in the Tree". PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art. 38 (3): 27–28. doi:10.1162/PAJJ_a_00331. ISSN 1520-281X. JSTOR 26386804. S2CID 57559845. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- McCaffrey, Robert (24 September 2020). "Alexander McQueen: The Sublime and Melancholy". The Fashion Studies Journal. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- Sheean, Jacqueline (2 October 2018). "A (New) Specter Haunts Europe: the Political Legibility of Spain's Hologram Protests". Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies. 19 (4): 469. doi:10.1080/14636204.2018.1524995. ISSN 1463-6204. S2CID 149971456.

- Tegan, Mary Beth (1 October 2021). ""The Contagion of Her Wretchedness": Rousing Interest in the Highland Widows of Scott and McQueen". Essays in Romanticism. 28 (2): 95. doi:10.3828/eir.2021.28.2.4. ISSN 2049-6702. S2CID 239506478. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

External links

- "Women's Fall / Winter 06: "The Widows of Culloden"". Alexander McQueen. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- Alexander McQueen | Women's Autumn/Winter 2006 | Runway Show on YouTube

- Metropolitan Museum of Art: Widows of Culloden finale on Vimeo

- Production stills and concept art from designer Joseph Bennett