The Hunger (Alexander McQueen collection)

The Hunger (Spring/Summer 1996) is the seventh collection by British designer Alexander McQueen for his eponymous fashion house. The collection was inspired by The Hunger, a 1983 erotic horror film featuring vampires. Typically for McQueen in the early stages of his career, the collection centred around sharply tailored garments and emphasised female sexuality. McQueen had limited financial backing, so the collection was created on a minimal budget.

The runway show for The Hunger was staged on 23 October 1995, during London Fashion Week. The venue was the Natural History Museum of London. Like his previous professional shows, The Hunger was styled with imagery of violence and death, most prominently a corset of translucent plastic with real worms encased within. Many of the people who worked on The Hunger with McQueen would go on to become longtime collaborators. Garments from The Hunger appeared in both stagings of the retrospective exhibition Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty.

Background

British designer Alexander McQueen was known in the fashion industry for his imaginative, sometimes controversial designs, and dramatic fashion shows.[1] He began his career in fashion as an apprentice with Savile Row tailors Anderson & Sheppard before briefly joining Gieves & Hawkes as a pattern cutter.[2][3] His work on Savile Row earned him a reputation as an expert tailor.[1] In October 1990, at the age of 21, McQueen began the eighteen-month masters-level course in fashion design at Central Saint Martins (CSM), a London art school.[4][5] McQueen met a number of his future collaborators at CSM, including Simon Ungless.[6] He graduated with his master's degree in fashion design in 1992. His graduation collection, Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims, was bought in its entirety by magazine editor Isabella Blow, who became his mentor and his muse.[7]

McQueen's reputation for shocking runway shows began early. The sexualised clothing and aggressive styling in his first professional show, Nihilism (Spring/Summer 1994), was described by The Independent as a "horror show".[8] The follow-up, Banshee (Autumn/Winter 1994), featured a model pretending to put a finger in her vagina on the runway.[9]

McQueen had no financial backing at the beginning of his career, so his early collections were created on minimal budgets. He purchased whatever cheap fabric or fabric scraps were available.[10] Collaborators often worked for minimal pay or were paid in garments. Some agreed to work for free because they were interested in working with McQueen, while others who had been promised compensation were simply never paid.[11][12] Many actually wound up paying out of pocket for things like fabric and notions.[13] Although McQueen had secured some funding from Italian fashion manufacturer Eo Bocci following the success of The Birds (Spring/Summer 1995), money was still tight.[14][15]

Concept and creative process

The collection was inspired by The Hunger, a 1983 erotic horror film featuring a love triangle between two vampires and a human doctor.[16] As was typical for McQueen, the collection focused on sharp tailoring and experimental materials.[17] He made use of natural materials including feathers, and incorporated thorn and feather prints.[16] The most significant piece from the collection is a moulded corset created from two layers of translucent plastic encasing real worms, juxtaposing sexuality with imagery suggesting decay.[18][16] The layers were pre-moulded on a fit model, and McQueen assembled the corset with fresh, live worms two hours before the show.[19]

Recurring design flourishes include extreme cutouts and slashes, evoking self-harm by cutting, to which McQueen was prone.[19][16] Some elements pointed back at his graduation collection, Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims (1992), including sharply-pointed collars and trimmings that imitated human flesh or blood.[16][20] The visual motif of spilled blood evoked the association of vampires with drinking and exchanging blood to create new vampires.[20]

Jeweller Shaun Leane, who had created watch chains and fobs for Highland Rape (Autumn/Winter 1996), created accessories for The Hunger, including the "Tusk" earring.[lower-alpha 1][21][16]

Runway show

The runway show for The Hunger was staged on 23 October 1995, as the finale of that season's London Fashion Week.[22] The venue was a tent on the East Lawn at the Natural History Museum of London.[22][16] Although McQueen was now being supported to some extent by Eo Bocci, the show's budget was reportedly only £600.[13]

Sam Gainsbury, who had previously served as casting director for The Birds (Spring/Summer 1995), returned to produce the show.[23][16] Icelandic singer Björk produced the show's soundtrack.[16] The show was dedicated to Katy England, McQueen's friend who was by then serving as his creative director.[16]

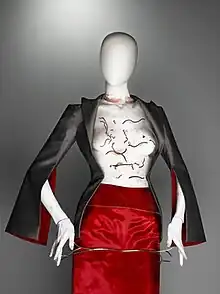

The Hunger comprised 95 looks, 28 of which were, for the first time in McQueen's career, menswear.[24][16] The worm corset appeared as Look 64, was styled with a tailored grey jacket and red silk skirt, with a silver "stirrup" by Shaun Leane worn over the skirt.[25][24]

Reception and analysis

In an analysis of McQueen's Gothic leanings, Catherine Spooner pointed to the worm corset as one of his "most inherently Gothic garments". For her, the worms referenced Gothic themes of death, decay, and, with "their similarity to leeches, the vampires with which the collection was associated".[26] She viewed the ensemble through the lens of the "abject", developed by fashion philosopher Julia Kristeva: the revulsion experienced during encounters with anything which "does not respect borders, positions, rules".[26] Spooner felt that the corset played with bodily boundaries by framing the worms as both within and outside the body. Additionally, the tailored jacket and structured corset contrast with the random placement of the worms, juxtaposing "structure countered with chaos, [and] beauty with horror".[26]

Fashion historian Alistair O'Neill discussed The Hunger in an essay that analysed McQueen's reliance on film for inspiration. The Hunger, he felt, showcased McQueen's ability to translate tropes and themes from cinema into fashion, serving as "part commentary, part intervention".[20]

Legacy

Sam Gainsbury, working with her partner Anna Whiting, went on to produce all of McQueen's runway shows.[16] Leane and McQueen worked together until McQueen's death in 2010.[27] The Tusk earring design Leane created for the show became a brand signature for his jewellery house.[27]

McQueen drew on another vampire film, Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), for his untitled Autumn/Winter 2006 menswear collection.[28]

McQueen returned to the moulded bodice concept several times throughout his career.[18] For the Givenchy haute couture Spring/Summer 1998 season, he showed a clear bodice filled with butterflies, which Caroline Evans found reminiscent of the worm corset from The Hunger.[29]

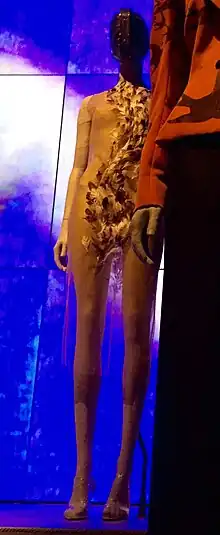

The worm corset and a Tusk earring by Shaun Leane appeared in both stagings of the retrospective exhibition Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2011 and at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 2015.[30] Look 58, a feathered sheer dress, was added for the second staging, which included 66 items that did not appear in the original.[24][31]

Notes

- Kate Bethune's Encyclopedia of Collections incorrectly reports The Hunger as McQueen's first collaboration with Leane.[16]

References

- Vaidyanathan, Rajini (12 February 2010). "Six ways Alexander McQueen changed fashion". BBC Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Doig, Stephen (30 January 2023). "How Alexander McQueen changed the world of fashion – by the people who knew him best". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023.

- Carwell, Nick (26 May 2016). "Savile Row's best tailors: Alexander McQueen". GQ. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- Wilson 2015, p. 70.

- Callahan 2014, pp. 24–25, 27.

- Callahan 2014, p. 103.

- Blow, Detmar (14 February 2010). "Alex McQueen and Isabella Blow". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- Evans 2003, p. 141.

- Thomas 2015, p. 118.

- Thomas 2015, p. 123.

- Wilson 2015, pp. 110–111, 147.

- Thomas 2015, pp. 153–154.

- Frankel 2015, p. 74.

- Callahan 2014, p. 104.

- Wilson 2015, pp. 137–138.

- Bethune 2015, p. 307.

- Frankel 2011, p. 20.

- Evans 2015, p. 191.

- Thomas 2015, p. 155.

- O'Neill 2015, p. 273.

- Woolton, Carol (13 March 2015). "Alexander McQueen's legacy in jewellery". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Fairer & Wilcox 2016, p. 338.

- Bolton 2015, p. 18.

- "Alexander McQueen Spring 1996 Ready-to-Wear Collection". Vogue. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Spooner 2015, p. 152.

- Spooner 2015, p. 151.

- Royce-Greensill, Sarah (29 March 2015). "Shaun Leane remembers McQueen". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- Spooner 2015, p. 143.

- Evans 2015, p. 192.

- Bolton 2011, pp. 234–235.

- Conti, Samantha (13 March 2015). "Celebrating the Opening of Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

Bibliography

- Bolton, Andrew (2011). Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-412-5. OCLC 687693871.

- Frankel, Susannah (2011). "Introduction". In Bolton, Andrew (ed.). Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. New York City: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 17–27. ISBN 978-1-58839-412-5.

- Callahan, Maureen (2014). Champagne Supernovas: Kate Moss, Marc Jacobs, Alexander McQueen, and the '90s Renegades Who Remade Fashion. New York City: Touchstone Books. ISBN 978-1-4516-4053-3.

- Deniau, Anne (2012). Love Looks Not with the Eyes: Thirteen Years with Lee Alexander McQueen. New York City: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-1-61312-415-4. OCLC 785067241.

- Esguerra, Clarissa M.; Hansen, Michaela (2022). Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse. New York City: Delmonico Books. ISBN 1-63681-018-7. OCLC 1289986708.

- Evans, Caroline (2003). Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10192-8.

- Fairer, Robert; Wilcox, Claire (2016). Alexander McQueen: Unseen. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-22267-X. OCLC 946216643.

- Fox, Chloe (2012). Vogue On: Alexander McQueen. Vogue on Designers. London: Quadrille Publishing. ISBN 1849491135. OCLC 828766756.

- Gleason, Katherine (2012). Alexander McQueen: Evolution. New York City: Race Point Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61058-837-9. OCLC 783147416.

- Homer, Karen (2023). Little Book of Alexander McQueen: The Story of the Iconic Brand. London: Welbeck Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-80279-270-6.

- Honigman, Ana Finel (2021). What Alexander McQueen Can Teach You About Fashion. Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-5906-5.

- Knox, Kristin (2010). Alexander McQueen: Genius of a Generation. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-3223-4. OCLC 794296806.

- Loschek, Ingrid (2009). When Clothes Become Fashion: Design and Innovation Systems. Oxford: Berg Publishers. doi:10.2752/9781847883681. ISBN 978-0-85785-144-4. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- Thomas, Dana (2015). Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano. New York City: Penguin Publishing. ISBN 978-1-101-61795-3. OCLC 951153602.

- Watt, Judith (2012). Alexander McQueen: The Life and the Legacy. New York City: Harper Design. ISBN 978-1-84796-085-6. OCLC 892706946.

- Wilcox, Claire, ed. (2015). Alexander McQueen. New York City: Abrams Books. ISBN 978-1-4197-1723-9. OCLC 891618596.

- Bethune, Kate. "Encyclopedia of Collections". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 303–326.

- Bolton, Andrew. "In Search of the Sublime". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 15–21.

- Evans, Caroline. "Modelling McQueen: Hard Grace". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 189–202.

- Faiers, Jonathan. "Nature Boy". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 123–137.

- Frankel, Susannah. "The Early Years". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 69–79.

- O'Neill, Alistair. "The Shining and Chic". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 261–280.

- Skogh, Lisa. "Museum of the Mind". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 178–188.

- Spooner, Catherine. "A Gothic Mind". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 141–158.

- Wood, Ghislaine. "Clan MacQueen". In Wilcox (2015), pp. 51–56.

- Wilson, Andrew (2015). Alexander McQueen: Blood Beneath the Skin. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-7674-3. OCLC 1310585849.