Health in China

Health in China is a complex and multifaceted issue that encompasses a wide range of factors, including public health policy, healthcare infrastructure, environmental factors, lifestyle choices, and socioeconomic conditions.[1][2]

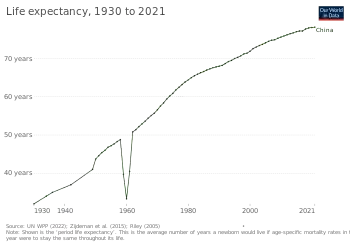

China has made significant progress in improving public health over the past few decades, with life expectancy increasing from 67.8 years in 1981 to 76.7 years in 2019. The Chinese government has implemented a range of health policies and initiatives, including the Healthy China 2030 program, which aims to improve public health outcomes by addressing major health challenges such as chronic diseases, infectious diseases, and environmental health hazards.[1][3][4]

However, China still faces significant health challenges, including air pollution, food safety concerns, a growing burden of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and an aging population.[1][5]

The healthcare system in China is a mix of public and private providers, with the government responsible for providing basic healthcare services to the population. However, there are significant disparities in access to healthcare between urban and rural areas, as well as between different socioeconomic groups.

In recent years, China has made efforts to improve its healthcare infrastructure, including investing in the development of primary healthcare facilities and expanding health insurance coverage. Additionally, the government has implemented a number of public health campaigns, such as anti-smoking and anti-obesity initiatives.[6][7]

Despite these efforts, there is still much work to be done to improve health outcomes in China. Ongoing efforts are needed to address the root causes of health disparities and to promote healthy lifestyles and behaviors among the population.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[8] finds that China is fulfilling 98.4% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income.[9] When looking at the right to health with respect to children, China achieves 98.6% of what is expected based on its current income.[10] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves 97% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income. When considering the right to reproductive health, the nation is fulfilling 99.6% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available. Overall, China falls into the "good" category when evaluating the right to health.[11]

Post-1949 history

1949 - 1976

An emphasis on public health and preventive treatment characterized health policy from the beginning of the 1950s. At that time the party began to mobilize the population to engage in mass "patriotic health campaigns" aimed at improving the low level of environmental sanitation and hygiene and attacking certain diseases. These public health measures contributed to a major decrease in mortality.[12]: 81

In 1956, China began a public health campaign to eliminate schistosoma-carrying snails.[13] Beginning in 1958, the "four pests" campaign sought to eliminate rats, sparrows, flies, and mosquitoes. Particular efforts were devoted in the health campaigns to improving water quality through such measures as deep-well construction and human-waste treatment. Only in the larger cities had human waste been centrally disposed of. In the countryside, where "night soil" has always been collected and applied to the fields as fertilizer, it was a major source of disease. Since the 1950s, rudimentary treatments such as storage in pits, composting, and mixture with chemicals have been implemented. As a result of preventive efforts, such epidemic diseases as cholera, bubonic plague, typhoid fever, and scarlet fever have almost been eradicated. The mass mobilization approach proved particularly successful in the fight against syphilis, which was reportedly eliminated by the 1960s. The incidence of other infectious and parasitic diseases was reduced and controlled.

Political turmoil and famine following the failure of the Great Leap Forward led to the starvation of 20 million people in China. Beginning in 1961 the recovery had more moderate policies inaugurated by President Liu Shaoqi ended starvation and improved nutrition. The coming of the Cultural Revolution weakened epidemic control, causing a rebound in epidemic diseases and malnutrition in some areas.

With the Cultural Revolution (1964-1976), Mao Zedong introduced a new approach to public health, especially in rural areas.[2] In his June 26 Directive, Mao prioritized healthcare and medicine for rural people throughout the country.[14]: 362 As a result, clinics and hospitals sent their staff on medical tours of rural areas.[14]: 362

Rural cooperative medical systems provided subsidized health care to rural residents.[2] One aspect of this system was barefoot doctors, who received some training and then delivered primary care medicine to those who needed it.[2] Barefoot doctors were a good contribution to primary health systems in China during the Cultural Revolution. It encompasses all principles stated in primary health care. Community participation is possible because the team is composed of village health workers in the area. There is equity because it was more available and combined western and traditional medicines. Intersectoral coordination is achieved by preventive measures rather than curative. Lastly it is comprehensive using rural practices rather than urban ones.[15]

1976 - 2003

By the late 1970s, China's national health system covered almost the entire urban population and 85% of the rural population.[16] The World Bank described this success as "an unrivaled achievement among low-income countries."[16]

The "barefoot doctor system" was based in the people's communes.[17] In the 1980s, with the disappearance of the people's communes and the rural cooperative medical system, the barefoot doctor system lost its base and funding.[18] The Chinese government began to push for privatization of health care and, as a result, stopped providing necessary funding.[19] Instead, according to Blumenthal et al. (2005), individual towns were now responsible for ensuring that people were receiving adequate health care, which caused disparities between wealthier and poorer regions.[18] Additionally, the decollectivization of agriculture resulted in a decreased desire on the part of the rural populations to support the collective welfare system, of which health care was a part. In 1984 surveys showed that only 40 to 45 percent of the rural population was covered by an organized cooperative medical system, as compared with 80 to 90 percent in 1979.

This shift entailed a number of important consequences for rural health care. The lack of financial resources for the cooperatives resulted in a decrease in the number of barefoot doctors, which meant that health education and primary and home care suffered and that in some villages sanitation and water supplies were checked less frequently. Also, the failure of the cooperative health care system limited the funds available for continuing education for barefoot doctors, thereby hindering their ability to provide adequate preventive and curative services. The costs of medical treatment increased, deterring some patients from obtaining necessary medical attention. If the patients could not pay for services received, then the financial responsibility fell on the hospitals and commune health centers, in some cases creating large debts.

Consequently, in the post-Mao era of modernization, the rural areas were forced to adapt to a changing health care environment. Many barefoot doctors went into private practice, operating on a fee-for-service basis and charging for medication. But soon farmers demanded better medical services as their incomes increased, bypassing the barefoot doctors and going straight to the commune health centers or county hospitals. A number of barefoot doctors left the medical profession after discovering that they could earn a better living from farming, and their services were not replaced. The leaders of brigades, through which local health care was administered, also found farming to be more lucrative than their salaried positions, and many of them left their jobs. Many of the cooperative medical programs collapsed. Farmers in some brigades established voluntary health-insurance programs but had difficulty organizing and administering them.

Their income for many basic medical services limited by regulations, Chinese grassroots health care providers has supported themselves by charging for giving injections and selling medicines. This has led to a serious problem of disease spread through health care as patients received too many injections and injections by unsterilized needles. Corruption and disregard for the rights of patients have become serious problems in the Chinese health care system.

The Chinese economist, Yang Fan, wrote in 2001 that lip service being given to the old socialist health care system and deliberately ignoring and failing to regulate the actual private health care system is a serious failing of the Chinese health care system. "The old argument that "health is a kind of welfare to save lives and assist the injured" is so far removed from reality that things are really more like its opposite. The welfare health system supported by public funds essentially exists in name only. People have to pay for most medical services on their own. Considering health to be still a "welfare activity" has for some time been a major obstacle to the development of proper physician - patient relationship and to the law applicable to that relationship."[20]

Despite the decline of the public health care system during the first decade of the reform era, Chinese health improved sharply as a result of greatly improved nutrition, especially in rural areas, and the recovery of the epidemic control system, which had been neglected during the Cultural Revolution.

2003 - present

From late 2002 to early 2003 the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak began in China and spread across the world.[21] In the early stages of disease spread, the Chinese government withheld information and may have contributed to the further spreading of the disease.[6] In addition, China's health care system was still fairly decentralized, with a noticeable lack of oversight and little potential for rapid coordination.[22][18] Thus, the SARS epidemic highlighted the need for the Chinese government to begin restructuring its health care distribution.[18] One big issue many have pointed out, including Blumenthal (2005) and Yip et al. (2008), is that much of China's population does not have access to affordable health insurance.[19][18] As a solution, the Chinese government planned to provide universal health insurance to all citizens by 2020.[19][18] To get closer to this goal, the Chinese government began a health insurance program known as the New Cooperative Health Scheme, which gave mainly rural Chinese residents limited insurance coverage for emergencies.[19] Alongside the insurance measures, the Chinese government returned to the successful public health endeavors of the Cultural Revolution by instituting community health centers in urban neighborhoods with the goal of providing affordable options to hospital care.[19] Dong (2008) also mentions that China has been working to reinstate the cooperative medical systems in rural areas by pushing for state-funded health centers to be established.[22] That being said, some studies, such as Dib (2008) have shown that the quality of health care in rural areas still varies widely depending on wealth of the region.[23] Despite debates surrounding the effectiveness of China's revamped health system, the COVID-19 outbreak of 2019-2020 has shown that things have changed since the SARS outbreak of 2003.[3] Specifically, the Chinese government notified their citizens and the rest of the world of the first cases of the outbreak much sooner than SARS in 2003. While it took around four to five months for a public statement on SARS after the first case, it only took about one month for the COVID-19.[3] Because their response escalated more quickly, the food market thought to be at the center of the outbreak was also shut down sooner than the one that had been the source of the 2003 SARS outbreak.[3] In addition to a more rapid response, the Chinese government quickly established committees and consortia made up of both Chinese and international experts to begin exploring methods to combat the outbreak.[3]

Health indicators

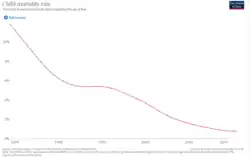

Some measures used to indicate health include Total Fertility Rate, Infant Mortality Rate, Life Expectancy, Crude Birth and Death Rate. As of 2017, China has a Total Fertility Rate of 1.6 children born per woman, an Infant Mortality rate of 10 deaths per 1000 live births, Crude Birth Rate of 13 births per 1000 people and a Death Rate of 7 deaths per 1000 people[24][25]. Since 1949, China had a huge improvement in population's health. There are health related parameters:

| 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy | 41.6 | 31.6 | 62.7 | 66.1 | 69.5 | 72.1 | 75.0 |

| Total Fertility Rate | 5.3 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Infant Mortality Rate | 195.0 | 190.0 | 79.0 | 47.2 | 42.2 | 30.2 | 12.9 |

| Under 5 Mortality Rate/Child mortality | 317.1 | 309.0 | 111 | 61.3 | 54.0 | 36.9 | 14.9 |

| Maternal Mortality Ratio | 164.5 | 88.0 | 57.5 | 26.5 |

- data from www.gapminder.org.[26]

In general, all indices showed improvement except the drop around 1960 due to the failure of the Great Leap Forward, which led to the starvation of tens of millions of people. From 1950 to 2012, life expectancy nearly doubled (41.6-75.1). Total Fertility Rate changed from 5.3 to 1.7 which mainly caused by One-child policy. Infant Mortality rate and Under-5 mortality rate went down sharply. Though there is no data from 1963 to 1967, we can see the trend. The gap between IMR and U5MR became smaller and smaller, which indicates health in children has been promoted. Maternal Mortality Ratio isn't shown in the graph due to having insufficient data, but it did go down from 164.5(1980) to 26.5(2011).

One-Child Policy

Created in 1979, under Deng Xiaoping, the One-Child Policy incentivized families to have children later and to only have one child or risk penalization.[27] The One-Child Policy was a program created by the Chinese government as a reaction to the increasing population during the 1970s, that was thought to have negatively impacted China's economic growth. Implementation of the program included rewarding families who followed the program, fining families who resisted the policy, offering birth control/ contraceptives, and in some cases forced abortions.[28] The policy was unevenly implemented throughout China and was easier established in urban areas rather than rural, because of ideals about family size and gender preferences. Prior to the One-Child Policy, the Chinese government had encouraged families to have more children in order to increase the future workforce, however, this promotion made the population of China in the 1970s increase at an alarming rate.[29] Additionally, voluntary programs, involving family planning and contraceptive use, were proposed before the One-Child Policy was fully enforced.[28]

Effects of the One-Child Policy

In 2015, the one-child policy of Deng Xiaoping was replaced by a two-child policy, which increased the number of "allowed" children to two.[30] With this, scholars began evaluating the effects of the one-child policy. The One-Child Policy was successful in halting China's increasing population and decreased both the birth rate and population, however, the harsh enforcement of the policy created long-term changes to some of China's health indicators. For instance, favoring males over female children lead to many forced abortions, infanticide and abandoned female children which led to an imbalance of men to women in China.[31] Additionally, birth rates and rate of natural increase decreased as a result of the One-Child Policy.[32] Other consequences of the One-Child Policy include difficulties accessing education and employment as a result of being an undocumented birth.[28]

In terms of positive outcomes, as Zeng and Hesketh (2016) explain, the Chinese government cites the decreased fertility rate resulting from the one-child policy as a determining factor in China's rapidly increasing GDP.[30] However, Zeng and Hesketh (2016) as well as Zhang (2017) also mention that other scholars argue China's fertility rate would have decreased as the country became more and more developed, regardless of whether the one-child policy had been in place or not.[30][33] Zhang (2017) notes that one predicted positive outcome of having less children was that families would invest more money and other resources in the children they did have, leading to a healthier and more successful population.[33] However, follow-up studies on this claim have examined child education outcomes and found that the effects of the one-child policy on education rates was "not statistically significant".[33]

Dependency ratio

China's dependency ratio is unfavorable because of the policy and its elderly population (65+) will outgrow the working aged people. The elderly population in China is highly reliant on the working aged people for support and the number of dependents (children 0–14, adults 65+) are increasing compared to the number of working aged people. China's population is aging and the number of children born is less than the replacement rate.[32]

Medical issues in China

Smoking

Smoking is very prevalent in China. In fact, China has the largest smoking population in the world.[34] One of the most direct results of the popularity of smoking in China is lung cancer, and lung cancer is the single biggest contributor to the frequency of cancer in China.[34] Parascandola and Xiao (2015) refer to the prevalence of lung cancer in China as an epidemic.[34] Collecting data on the topic is complicated by the fact that lung cancer can also stem from China's air pollution.[34] Regardless, smoking related illnesses killed 1.2 million in the People's Republic of China; however, the state tobacco monopoly, the China National Tobacco Corporation, supplies 7 to 10% of government revenues, as of 2011, 600 billion yuan, about 100 billion US dollars.[35] As a result, although movements for tobacco smoking cessation exist and have been gaining popularity, the financial benefit of the smoking industry stands in the way of more effective cessation programming.[36] In addition, the practice of smoking is intertwined with Chinese culture which further complicates the relationship between China and smoking. Smoking is central to socialization in many public spaces, although mainly men participate in the practice.[36] With these complicating factors, it has been difficult to effectively reduce tobacco use and smoking. For example, a Chinese official in 2007 mentioned that if smoking were banned, it would result in social upheaval.[36] Still, interestingly, tobacco use and smoking has decreased from about 30% prevalence to 25% percent prevalence in 2016, a sign that the tide may be changing.[37]

Sex education, contraception, and women's health

Sex education lags in China due to cultural conservatism. From ancient China to the first half of the 20th century, formal sex education was not taught. Instead, a woman's parents were mostly responsible for her sex education after she is wed.[38] Many Chinese feel that sex education should be limited to biological science. Combined with migration of young unmarried women to the cities, lack of knowledge of contraception has resulted in increasing numbers of abortions by young women.[39]

The Basic Health Services Project piloted strategies to ensure equitable access to China's rural health system; health outcomes for women improved significantly, with substantial declines in maternal mortality due to increased coverage of maternal health services.[40]

SARS

Although not identified until later, China's first case of a new, highly contagious disease, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), occurred in Guangdong in November 2002, and within three months the Ministry of Health reported 300 SARS cases and five deaths in the province. Dr. Jiang Yanyong exposed the level of danger the SARS outbreak posed to China.[41][42] By May 2003, some 8,000 cases of SARS had been reported worldwide; about 66 percent of the cases and 349 deaths occurred in China alone. By early summer 2003, the SARS epidemic had ceased. A vaccine was developed and first-round testing on human volunteers completed in 2004.

The 2002 SARS in China demonstrated at once the decline of the PRC epidemic reporting system, the deadly consequences of secrecy on health matters and, on the positive side, the ability of the Chinese central government to command a massive mobilization of resources once its attention is focused on one particular issue. Despite the suppression of news regarding the outbreak during the early stages of the epidemic, the outbreak was soon contained and cases of SARS failed to emerge.[43] Obsessive secrecy seriously delayed the isolation of SARS by Chinese scientists.[44] On 18 May 2004, the World Health Organization announced the PRC free of further cases of SARS.[45]

COVID-19 pandemic

A coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, started in December 2019.[46] It was first identified in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei, China.[47][48] Its severity has surpassed of the 2003 SARS outbreak.[49] On 30 January, the outbreak was declared to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO).[50] Wider concerns about consequences of the outbreak include political and economic instability. Political fallout has included the firing of several local leaders of the Chinese Communist Party for their poor response to the outbreak.[51] Outbreak-related incidents of xenophobia and racism against people of Chinese and East Asian descent have been reported in several countries.[52][53][54][55] The spread of misinformation and disinformation about the virus, primarily online, has been described as an "infodemic" by the WHO.[56]

Hepatitis B

Work with the CDC has created goals of decelerating the spread of Hepatitis B through immunization efforts.[57] However, Hepatitis B is still widespread in China and has been determined by Wang et al. (2019) to have "higher intermediate prevalence (5-7.99%)".[58] In fact, no country has a higher prevalence of Hepatitis B than China and one third of the world's Hepatitis B-afflicted individuals are thought to reside in China.[59] Hepatitis B in China was even described as an "epidemic" in Chen et al. (2018).[59] Some socioeconomic factors that contribute to the continued prevalence of Hepatitis B in China are first the high medical cost related to treatment.[59] Second, the stigma that surrounds the disease causes the importance of Hepatitis B testing to go undiscussed in that people who disclose their Hepatitis B positive status may be discriminated against.[60] These combine to cause a situation where many people in China do not even realize that they are infected with the disease and thus unknowingly may succumb to the disease or pass it on to others.[59]

HIV and AIDS

The AIDS disaster of Henan in the mid-1990s is estimated to be the largest man-made health catastrophe, affecting five-hundred thousand to one million persons. It was also in Hebei, Anhui, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Hubei and Guizhou.[61] HIV was transmitted via blood sale. Blood plasma mixture from several persons was returned so that same person could give blood up to 11 times a day.[62] The disaster was only recognized in 2000 and found out abroad in 2001. Pensioner Gao Yaojie sold her house to deliver data leaflets of HIV to people, while officials tried to prevent her. Some local officials and politicians were involved in the blood sale. In 2003 only 2.6% of Chinese knew that a condom could protect from AIDS.[63]

China blocked by police protest over ineffective drug treatments, cancelled meetings on HIV groups, closured office of the AIDS organization, and detained or put under house arrest prominent AIDS activists such as 2005 Reebok Human Rights Award winner Li Dan, eighty-year-old AIDS activist Dr. Gao Yaojie, and the husband-and-wife HIV activist team of Hu Jia (activist) and Zeng Jinyan.[64]

China, similar to other nations with migrant and socially mobile populations, has experienced increased incidences of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). By the mid-1980s, some Chinese physicians recognized HIV and AIDS as a serious health threat but considered it to be a "foreign problem". As of mid-1987 only two Chinese citizens had died from AIDS and monitoring of foreigners had begun. Following a 1987 regional World Health Organization meeting, the Chinese government announced it would join the global fight against AIDS, which would involve quarantine inspection of people entering China from abroad, medical supervision of people vulnerable to AIDS, and establishment of AIDS laboratories in coastal cities. Within China, the rapid increase in venereal disease, prostitution and drug addiction, internal migration since the 1980s and poorly supervised plasma collection practices, especially by the Henan provincial authorities, created conditions for a serious outbreak of HIV in the early 1990s.[65][66][67]

As of 2005 about 1 million Chinese have been infected with HIV, leading to about 150,000 AIDS deaths. Projections are for about 10 million cases by 2010 if nothing is done. Effective preventive measures have become a priority at the highest levels of the government, but progress is slow. A promising pilot program exists in Gejiu partially funded by international donors.

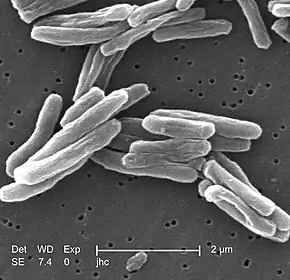

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a major public health problem in China, which has the world's second largest tuberculosis epidemic (after India). Progress in tuberculosis control was slow during the 1990s. Detection of tuberculosis had stagnated at around 30% of the estimated total of new cases, and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis was a major problem. These signs of inadequate tuberculosis control can be linked to a malfunctioning health system. Prevalent smoking aggravates its spread.

Leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, was officially eliminated at the national level in China by 1982, meaning prevalence is lower than 1 in 100,000. There are 3,510 active cases today. Though leprosy has been brought under control in general, the situation in some areas is worsening, according to China's Ministry of Health.[68]

Malaria

Plasmodium vivax malaria is the most common malaria in China, followed by P. falciparum malaria, while Plasmodium vivax malaria and Plasmodium ovale malaria are less common. P. falciparum malaria occurs mainly in the southwest and Hainan, while P. vivax malaria occurs in the northeast, north and northwest of China.[69] [70]

Since the 1950s, Chinese health authorities have worked to detect and prevent the spread of malaria by providing prophylactic anti-malarial drugs to people at risk of malaria and treating patients, and in 1967 the Chinese government launched the research “Project 523”. This work resulted in the antimalarial artemisinin-based combination therapies.[71] One of the team members, Tu Youyou, was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work.[72]

In the 1980s, began to experiment on a large scale with the use of drugs to prevent malaria. By 1988, the use of nets greatly reduced the incidence of malaria. By the end of 1990, the number of malaria cases in China had fallen to 117,000, and deaths had been reduced by 95 per cent. China was free of malaria cases for four consecutive years starting in 2017. The World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that malaria had been eliminated in China in 2021.[73][74]

Mental health

100 million Chinese people have mental illnesses that are varying degrees of intensity.[75] Currently, dilemmas such as human rights versus political control, community integration versus community control, diversity versus centrally, huge demand but inadequate services seem to challenge the further development of the mental health service in the PRC. China has 17,000 certified psychologists, which is ten percent of that of other developed countries per capita.[75]

Nutrition

In the 2000–2002 period, China had one of the highest per capita caloric intakes in Asia, second only to South Korea and higher than countries such as Japan, Malaysia, and Indonesia. In 2003, daily per capita caloric intake was 2,940 (vegetable products 78%, animal products 22%); 125% of FAO recommended minimum requirement.

Malnutrition among rural children

China has been developing rapidly for the past 30 years. Though it has uplifted a huge number of people out of poverty, many social issues still remain unsolved. One of them is malnutrition among rural children in China. The problem has diminished but still remains a pertinent national issue. In a survey done in 1998, the stunting rate among children in China was 22 percent and was as high as 46 percent in poor provinces.[76][77] This shows the huge disparity between urban and rural areas. In 2002, Svedberg found that stunting rate in rural areas of China was 15 percent, reflecting that a substantial number of children still suffer from malnutrition.[78] Another study by Chen shows that malnutrition has dropped from 1990 to 1995 but regional differences are still huge, particularly in rural areas.[79]

In a recent report by The Rural Education Action Project on children in rural China, many were found to be suffering from basic health problems. 34% have iron deficiency anaemia and 40 percent are infected with intestinal worms.[80] Many of these children do not have proper or sufficient nutrition. Often, this causes them not being able to fully reap the benefits of education, which can be a ticket out of poverty.

One possible reason for poor nutrition in rural areas is that agricultural produce can fetch a decent price, and thus is often sold rather than kept for personal consumption. Rural families would not consume eggs that their hen lay but will sell it in the market for about 20 yuan per kilogram.[81] The money will then be spent on books or food like instant noodles which lack nutrition value compared to an egg. A girl named Wang Jing in China has a bowl of pork only once every five to six weeks, compared to urban children who have a vast array of food chains to choose from.

A survey conducted by China's Ministry of Health showed the kind of food consumed by rural households. 30 percent consume meat less than once a month. 23 percent consume rice or egg less than once a month.

In a 2008 Report on Chinese Children Nutrition and Health Conditions, West China still has 7.6 million poor children who were shorter and weigh lesser than urban children. These rural children were also shorter by 4 centimetres and 0.6 kilograms lighter than World Health Organization standards.[81] It can be concluded that children in West China still lack quality nutrition.

Epidemiological studies

The most comprehensive epidemiological study of nutrition ever conducted was the China-Oxford-Cornell Study on Dietary, Lifestyle and Disease Mortality Characteristics in 65 Rural Chinese Counties, known as the "China Project", which began in 1983.[82] Its findings are discussed in The China Study by T. Colin Campbell.

Environment and health

China's rapid development has led to numerous environmental problems which all have a direct impact on health. According to Kan (2009) the environmental issues include "outdoor and indoor air pollution, water shortages and pollution, desertification, and soil pollution".[83] Of these, Kan (2009) states that the most detrimental one is the outdoor air pollution for which China has become known.[83] In Liu et al.'s research (2018) on this issue specifically, the major health effects are listed as "including adverse cardiovascular, respiratory, pulmonary, and other health-related outcomes".[84] The air pollution is not limited to industrial cities. In fact, due to the fact that rural Chinese people still use fuels such as coal for cooking, the World Health Organization attributes more premature deaths to that sort of air pollution than to China's ambient air pollution.[83] In addition, many factories are located in the countryside, which exacerbates rural air pollution.[83] Despite China's notoriously poor air quality, Matus et al. (2011) have found that the severity of China's air pollution has been declining over the years.[85]

Finally, as described by Kan (2018) and Wu, et al. (1999) another major contributor to adverse health effects related to environmental issues is water pollution.[86][83] In rural areas, this is once again due to factories located nearby. In urban areas on the other hand, China's water sanitation systems have not yet caught up with the needs of the population.[86] As a result, the water is often contaminated with human waste and is not considered potable.[86] Ingestion of contaminated water has caused diseases such as cholera.[83]

Climate change

Climate change has a significant impact on the health of Chinese people. The high temperature has caused health risks for some groups of people, such as older people (≥65 years old), outdoor workers, or people living in poverty. In 2019, each person who is older than 65 years had to endure extra 13 days of the heatwave, and 26,800 people died because of the heatwave in 2019.

In the future, the probability rate of malaria transmission will increase 39-140 percent because of temperature increase of 1-2 degrees Celsius in south China.[87]Iodine deficiency

China has problems in certain western provinces in iodine deficiency.[88]

Infection from animals

The first known human contraction of Avian Influenza (bird flu), after contact with live poultry in February 2018, was diagnosed to a woman living in the Jiangsu Province of China.[89]

Pig-human transmission of the Streptococcus suis bacteria was reported in 2005, which led to 38 deaths in and around Sichuan province, an unusually high number. Although the bacteria exists in other pig rearing countries, the pig-human transmission has only been reported in China.[90]

Hygiene and sanitation

Many of China's water sources, including underground sources and rivers, have been heavily polluted because of industry and economic growth. Increased exposure to polluted water and air has created "cancer villages" and further health and environmental problems.[91] A majority of groundwater and shallow wells surveyed in China showed signs of heavy pollution, by measuring nitrate levels which indicate water contamination[91]

By 2002, 92 percent of the urban population and 8 percent of the rural population had access to an improved water supply, and 69 percent of the urban population and 32 percent of the rural population had access to improved sanitation facilities.

Although China has made great efforts of making sanitary facilities and safe water more accessible, there are water and sanitation disparities all over China. As of 2012, sanitary facilities were available to 69% of the Chinese people and 71% of water in China is piped, yet it is still difficult preserving drinking water that is affordable and efficient at a communal level. Additionally, water in both urban and rural areas of China are still vulnerable to disease, pollution, and contamination, with rural areas at higher risk of sewage contamination.[92]

The lack of sanitation in multiple areas of China has affected many student for decades. An absence of modern-day toilets and hand washing areas have directly affected students nationwide. The lack of reliable drinking water and sanitation areas, along with many others health issues, has directly led to 1/3 of young students in China having intestinal parasites.[93]

The Patriotic Health Campaign, first started in the 1950s, are campaigns aimed to improve sanitation and hygiene in China. UNICEF also plans to incorporate government programs and policies in order to improve normal health standards in China. The programs and policies are used to teach students about basic hygiene and form campaigns encouraging people to wash their hands with soap instead of water only.[93]

WHO in China

The World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution came into force on 7 April 1948, and China has been a Member since the beginning.

The WHO China office has increased its scope of activities significantly in recent years, especially following the major SARS outbreak of 2003. The role of WHO China is to provide support for the government's health programs, working closely with the Ministry of Health and other partners within the government, as well as with UN agencies and other organizations.

China's government with WHO assistance and support has strengthened public health in the nation. The current Five Year Plan incorporates public health in a significant way. The government has acknowledged that even as millions upon millions of citizens are prospering amid the country's economic boom, millions of others are lagging behind, with healthcare many cannot afford. The challenge for China is to strengthen its health care system across the spectrum, to reduce the disparities and create a more equitable situation regarding access to health care services for the population at large.

At the same time, in an ever-interconnected world, China has embraced its responsibility to global public health, including the strengthening of surveillance systems aimed at swiftly identifying and tackling the threat of infectious diseases such as SARS and avian influenza. Another major challenge is the epidemic of HIV/AIDS, a key priority for China.

The staff of the WHO Office in China are working with their national counterparts in the following areas:

- Healthcare systems development

- Immunization

- Tuberculosis control

- HIV/AIDS control

- Maternal health and child health

- Injury prevention

- Avian influenza control

- Food safety

- Tobacco control

- Non-communicable diseases control

- Environment and health

- Communicable diseases surveillance and response

In addition, WHO technical experts in specialty areas can be made available on a short-term basis, when requested by the Chinese government. China is an active, contributing member of WHO, and has made valuable contributions to global and regional health policy. Technical experts from China have contributed to WHO through their membership on various WHO technical expert advisory committees and groups.

See also

References

- "China Health Statistics Yearbook 2020". National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China.

- Zhang, Daqing; Unschuld, Paul U (November 2008). "China's barefoot doctor: past, present, and future". The Lancet. 372 (9653): 1865–1867. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61355-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 18930539. S2CID 44522656.

- Nkengasong, John (27 January 2020). "China's response to a novel coronavirus stands in stark contrast to the 2002 SARS outbreak response". Nature Medicine. 26 (3): 310–311. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0771-1. ISSN 1546-170X. PMC 7096019. PMID 31988464.

- Healthy China 2030: A Vision for Healthier Populations.

- "The State of Health in China". McKinsey & Company.

- Qiu, Wuqi; Chu, Cordia; Mao, Ayan; Wu, Jing (28 June 2018). "The Impacts on Health, Society, and Economy of SARS and H7N9 Outbreaks in China: A Case Comparison Study". Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2018: 2710185. doi:10.1155/2018/2710185. ISSN 1687-9805. PMC 6046118. PMID 30050581.

- "Healthcare System In China: How It Works".

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "China - Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "China - Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- "China - Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- Harrell, Stevan (2023). An Ecological History of Modern China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295751719.

- Kawai Fan; Honkei Lai (2008). "Mao Zedong's Fight Against Schistosomiasis". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 51 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0013. ISSN 1529-8795. PMID 18453723. S2CID 44475390.

- Xu, Youwei; Wang, Y. Yvon (2022). Everyday Lives in China's Cold War Military Industrial Complex: Voices from the Shanghai Small Third Front, 1964-1988. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9783030996871.

- Cueto, Marcos, 2004. The ORIGINS of Primary Health Care and SELECTIVE Primary Health Care" Am J Public Health 94 (11) 1864-1874

- Lin, Chun (2006). The transformation of Chinese socialism. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8223-3785-0. OCLC 63178961.

- Carrin, Guy; Ron, Aviva; Hui, Yang; Hong, Wang; Tuohong, Zhang; Licheng, Zhang; Shuo, Zhang; Yide, Ye; Jiaying, Chen; Qicheng, Jiang; Zhaoyang, Zhang (April 1999). "The reform of the rural cooperative medical system in the People's Republic of China: interim experience in 14 pilot counties". Social Science & Medicine. 48 (7): 961–972. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00396-7. ISSN 0277-9536. PMID 10192562.

- Blumenthal, David; Hsiao, William (15 September 2005). "Privatization and Its Discontents — The Evolving Chinese Health Care System". New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (11): 1165–1170. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 16162889.

- Yip, Winnie; Hsiao, William C. (1 March 2008). "The Chinese Health System At A Crossroads". Health Affairs. 27 (2): 460–468. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.460. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 18332503.

- "What Limits to Corruption in Health Care?" Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine in April 2001 Viewpoint Voice of China translated on the U.S. Embassy Beijing website. Accessed 7 February 2007

- Zhong, Nanshan; Zeng, Guangqiao (17 August 2006). "What we have learnt from SARS epidemics in China". BMJ. 333 (7564): 389–391. doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7564.389. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1550436. PMID 16916828.

- Dong, Zhe; Phillips, Michael R (15 November 2008). "Evolution of China's health-care system". The Lancet. 372 (9651): 1715–1716. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61351-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 18930524. S2CID 44564705.

- Dib, Hassan H.; Pan, Xilong; Zhang, Hong (1 July 2008). "Evaluation of the new rural cooperative medical system in China: is it working or not?". International Journal for Equity in Health. 7 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-7-17. ISSN 1475-9276. PMC 2459170. PMID 18590574.

- Data Center: International Indicators – Population Reference Bureau

- East Asia/Southeast Asia :: China — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency

- "Gapminder". gapminder.org.

- Explainer: What was China's one-child policy? - BBC News

- "one-child policy | Definition & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "BBC - GCSE Bitesize: Case study: China". Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Zeng, Yi; Hesketh, Therese (15 October 2016). "The effects of China's universal two-child policy". Lancet. 388 (10054): 1930–1938. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31405-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 5944611. PMID 27751400.

- The one-child policy in China - Centre for Public Impact (CPI)

- "BBC - GCSE Bitesize: Case study: China". Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Zhang, Junsen (February 2017). "The Evolution of China's One-Child Policy and Its Effects on Family Outcomes". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 31 (1): 141–160. doi:10.1257/jep.31.1.141. ISSN 0895-3309.

- Parascandola, Mark; Xiao, Lin (May 2019). "Tobacco and the lung cancer epidemic in China". Translational Lung Cancer Research. 8 (S1): S21–S30. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2019.03.12. ISSN 2218-6751. PMC 6546632. PMID 31211103.

- Cheng Li (October 2012). "The Political Mapping of China's Tobacco Industry and Anti-Smoking Campaign" (PDF). John L. Thornton China Center Monograph Series. Brookings Institution (5). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

...the tobacco industry is one of the largest sources of tax revenue for the Chinese government. Over the past decade, the tobacco industry has consistently contributed 7-10 percent of total annual central government revenues...

- Hao, Pei (5 September 2019). "China's cigarette smoking epidemic". SupChina. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Smoking prevalence, total (ages 15+) - China | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- CSIRO PUBLISHING | Reproduction, Fertility and Development

- "Face of Abortion in China: A Young, Single Woman" article by Jim Yardley in the New York Times 13 April 2007

- Huntingdon, Dale; Liu Yunguo, Liz Ollier, Gerry Bloom (January 2008). "Improving maternal health – lessons from the basic health services project in China" (PDF). DFID Briefing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kahn, Joseph (13 July 2007). "China Hero Doctor Who Exposed SARS Cover-Up Barred U.S. Trip For Rights Award". New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- "The 2004 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee for Public Service". Ramon Magsaysay Foundation. 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- "After Its Epidemic Arrival, SARS Vanishes". 15 May 2005. Jim Yardley. Accessed 17 April 2006.

- "Chinese Scientists Say SARS Efforts Stymied by Organizational Obstacles China Youth Daily interview with Chinese geneticist Yang Huanming and Chinese Academy of Sciences science policy researcher Chen Hao

- "China’s latest SARS outbreak has been contained, but biosafety concerns remain". 18 May 2004. World Health Organization. Accessed 17 April 2006.

- Schlein, Lisa (24 February 2020). "WHO: Coronavirus Epidemic Is Not Yet Pandemic". VoA News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) - China, 2020" (PDF). China CDC Weekly. 2: 1–10. 20 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020 – via Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team (17 February 2020). "[The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) in China]". Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi (in Chinese). 41 (2): 145–151. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. PMID 32064853. S2CID 211133882.

- "Deaths in China Surpass Toll From SARS". The New York Times. 9 February 2020. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Somvichian-Clausen, Austa (30 January 2020). "The coronavirus is causing an outbreak in America—of anti-Asian racism". The Hill. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Kuo, Lily (11 February 2020). "China fires two senior Hubei officials over coronavirus outbreak". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Young, Evan (31 January 2020). "'This is racism': Chinese-Australians say they've faced increased hostility since the coronavirus outbreak began". Special Broadcasting Service.

- Iqbal, Nosheen (1 February 2020). "Coronavirus fears fuel racism and hostility, say British-Chinese". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Coronavirus fears trigger anti-China sentiment across the globe". Global News. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Yeung, Jessie. "As the coronavirus spreads, fear is fueling racism and xenophobia". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Fake Facts Are Flying About Coronavirus. Now There's A Plan To Debunk Them". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "CDC Global Health - China". www.cdc.gov. 24 August 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Wang, Huai; Men, Peixuan; Xiao, Yufeng; Gao, Pei; Lv, Min; Yuan, Qianli; Chen, Weixin; Bai, Shuang; Wu, Jiang (18 September 2019). "Hepatitis B infection in the general population of China: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Infectious Diseases. 19 (1): 811. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4428-y. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 6751646. PMID 31533643.

- Chen, Shanquan; Li, Jun; Wang, Dan; Fung, Hong; Wong, Lai-yi; Zhao, Lu (21 April 2018). "The hepatitis B epidemic in China should receive more attention". The Lancet. 391 (10130): 1572. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30499-9. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 29695339. S2CID 13856592.

- Kan, Quancheng; Wen, Jianguo; Xue, Rui (18 July 2015). "Discrimination against people with hepatitis B in China". The Lancet. 386 (9990): 245–246. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61276-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 26194522. S2CID 5597937.

- Pekka Mykkänen, Kiina rynnistää huipulle, Gummerus/Nemo 2004, pages 314-318

- Johan Björksten, I mittens rike, Det historiska och moderna Kina, Bilda förlag 2006, pages 190-191(in Swedish)

- Pekka Mykkänen, Isonenä kurkistaa Kiinaan, Nemo 2006, pages. 145-147 (in Finnish)

- China: Stop HIV Not People Living With HIV China Should Fulfill Promises Made to Global Fund, Respect Rights, Human Rights Watch November 2007

- July 2001 compendium, U.S. Embassy Beijing website Recent Chinese Reports on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Accessed 23 May 2010 via Internet Archive of U.S. Embassy Beijing website.

- "Revealing the Blood Wound of the Spread of AIDS in Henan Province". usembassy-china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 18 October 2002.

- China Health News And the Henan Province Health Scandal Cover-up translation of a report by the PRC NGO Aizhi

- Chen XS, Li WZ, Jiang C, Ye GY (2001). "Leprosy in China: epidemiological trends between 1949 and 1998". Bull. World Health Organ. 79 (4): 306–12. hdl:10665/268303. PMC 2566398. PMID 11357209.

- Zhang, Q, Lai, S, Zheng, C (2014). "The epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria in China, 2004–2012: from intensified control to elimination". Malar J . 13: 419. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-419. PMC 4232696. PMID 25363492.

- Lu G, Zhou S, Horstick O, Wang X, Liu Y, Müller O (2014). "Malaria outbreaks in China (1990-2013): a systematic review". Malar J. 13: 269. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-269. PMC 4105761. PMID 25012078.

- Hsu E (2006). "Reflections on the 'discovery' of the antimalarial qinghao". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 61 (6): 666–670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02673.x. PMC 1885105. PMID 16722826.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015". NobelPrize.org.

- "从3000万例到零:中国被世卫组织认证为无疟疾国家". www.who.int (in Chinese).

- Feng, Xinyu; Zhang, Li; Tu, Hong; Xia, Zhigui (4 November 2022). "Malaria Elimination in China and Sustainability Concerns in the Post-elimination Stage". China CDC Weekly. 4 (44): 990–994. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2022.201. ISSN 2096-7071. PMC 9709298. PMID 36483989.

- "And now the 50-minute hour: Mental health in China". The Economist. 18 August 2007. p. 35. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- Park, A. and Wang, S., 2001. "China’s Poverty Statistics." China Economic Review 12:384–98

- Park, A. and Zhang, L., 2000. "Mother’s Education and Child Health in China’s Poor Areas." Mimeo, University of Michigan Department of Economics

- Svedberg, P. (2006) "Declining child malnutrition: a reassessment", International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 35, No. 5, pp. 1336-46

- Chen, C. 2000. "Fat Intake and Nutritional Status of Children in China." American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 72(Supplement):1368S–72S

- The Rural Education Action Project - REAP, http://reap.stanford.edu/ - a group of researchers from the Freeman Spogli Institute and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2008 – retrieved from www.ccap.org.cn/uploadfile/2011/0111/20110111054129822.doc on 11 February 2011

- "West China county improves rural children health with free eggs". China Daily. 7 December 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Brody, Jane E. "Huge Study Of Diet Indicts Fat And Meat", The New York Times, 8 May 1990.

- Kan, Haidong (December 2009). "Environment and Health in China: Challenges and Opportunities". Environmental Health Perspectives. 117 (12): A530-1. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901615. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 2799473. PMID 20049177.

- Liu, Wenling (2018). "Health Effects of Air Pollution in China". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 1471 (7): 1471. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071471. PMC 6068713. PMID 30002305.

- Matus, Kira (2012). "Health damages from air pollution in China" (PDF). Global Environmental Change. 22: 55–66. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.006. hdl:1721.1/61774.

- Wu, C (1999). "Water pollution and human health in China". Environmental Health Perspectives. 107 (4): 251–256. doi:10.1289/ehp.99107251. PMC 1566519. PMID 10090702.

- The Lancet (2021). "Climate and COVID-19: converging crises". The Lancet. 397 (10269): 71. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32579-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 33278352. S2CID 227315818.

- Google search for "iodine deficiency in China"

- "Human infection with avian influenza A(H7N4) virus – China". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Streptococcus suis Outbreak, Swine and Human, China" Archived 27 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine August 2005. Veterinary Service. Accessed 17 April 2006.

- "China's "war on water pollution" must tackle causes of deep groundwater pollution". Global Water Forum. 3 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "Home". Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- "Sanitation and Hygiene - UNICEF China Protecting children's rights". www.unicef.cn. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

External links

- China Health Care Association

- Chinese Preventive Medicine Association

- China Profile by World Health Organization (WHO Office in China)

- Chinese Ministry of Health Archived 12 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- China Medical Board

- Hospitals in China

Resources

- "Critical health literacy: a case study from China in schistosomiasis control"

- Children's Healthcare in China

- Health Information for Travelers to China Archived 3 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- China's Healthcare System: Improving Quality of Insurance, Service, and Personnel Reforming China’s Healthcare System Roundtable series held by the Brookings-Tsinghua Center at Tsinghua University

- The Current State of Public Health in China Annual Review of Public Health Vol. 25: 327-339 (Volume publication date April 2004)

- A Critical Review of Public Health in China August 2004 paper