International Brigades

The International Brigades (Spanish: Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed for two years, from 1936 until 1938. It is estimated that during the entire war, between 40,000 and 59,000 members served in the International Brigades, including some 10,000 who died in combat. Beyond the Spanish Civil War, "International Brigades" is also sometimes used interchangeably with the term foreign legion in reference to military units comprising foreigners who volunteer to fight in the military of another state, often in times of war.[1]

| International Brigades | |

|---|---|

Emblem of the International Brigades | |

| Active | 18 September 1936 – 23 September 1938 |

| Country | Albania, France, Italy, Germany, Poland, United States, Ireland, Yugoslavia, United Kingdom, Belgium, Canada, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Mexico, Argentina, Netherlands, and others... |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Paramilitary |

| Size | between 40,000 and 59,000 |

| Garrison/HQ | Albacete |

| Motto(s) |

|

| Engagements | Spanish Civil War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

| Part of a series on |

| Anti-fascism |

|---|

|

The headquarters of the brigade was located at the Gran Hotel,[2] Albacete, Castilla-La Mancha. They participated in the battles of Madrid, Jarama, Guadalajara, Brunete, Belchite, Teruel, Aragon and the Ebro. Most of these ended in defeat. For the last year of its existence, the International Brigades were integrated into the Spanish Republican Army as part of the Spanish Foreign Legion. The organisation was dissolved on 23 September 1938 by Spanish Prime Minister Juan Negrín in a vain attempt to get more support from the liberal democracies on the Non-Intervention Committee.

The International Brigades were strongly supported by the Comintern and represented the Soviet Union's commitment to assisting the Spanish Republic (with arms, logistics, military advisers and the NKVD), just as Portugal, Fascist Italy, and Nazi Germany were assisting the opposing Nationalist insurgency.[3] The largest number of volunteers came from France (where the French Communist Party had many members) and communist exiles from Italy and Germany. Many Jews were part of the brigades, being particularly numerous within the volunteers coming from the United States, Poland, France, England and Argentina.[4]

Republican volunteers who were opposed to Stalinism did not join the Brigades but instead enlisted in the separate Popular Front, the POUM (formed from Trotskyist, Bukharinist, and other anti-Stalinist groups, which did not separate Spaniards and foreign volunteers),[5] or anarcho-syndicalist groups such as the Durruti Column, the IWA, and the CNT.

Formation and recruitment

Using foreign communist parties to recruit volunteers for Spain was first proposed in the Soviet Union in September 1936—apparently at the suggestion of Maurice Thorez[6]—by Willi Münzenberg, chief of Comintern propaganda for Western Europe. As a security measure, non-communist volunteers would first be interviewed by an NKVD agent.

By the end of September, the Italian and French Communist Parties had decided to set up a column. Luigi Longo, ex-leader of the Italian Communist Youth, was charged to make the necessary arrangements with the Spanish government. The Soviet Ministry of Defense also helped, since they had an experience of dealing with corps of international volunteers during the Russian Civil War. The idea was initially opposed by Largo Caballero, but after the first setbacks of the war, he changed his mind and finally agreed to the operation on 22 October. However, the Soviet Union did not withdraw from the Non-Intervention Committee, probably to avoid diplomatic conflict with France and the United Kingdom.

The main recruitment center was in Paris, under the supervision of Soviet colonel Karol "Walter" Świerczewski. On 17 October 1936, an open letter by Joseph Stalin to José Díaz was published in Mundo Obrero, arguing that victory for the Spanish second republic was a matter not only for Spaniards but also for the whole of "progressive humanity"; in short order, communist activists joined with moderate socialist and liberal groups to form anti-fascist "popular front" militias in several countries, most of them under the control of or influenced by the Comintern.[7]

Entry to Spain was arranged for volunteers, for instance, a Yugoslav, Josip Broz, who would become famous as Marshal Tito, was in Paris to provide assistance, money, and passports for volunteers from Eastern Europe (including numerous Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War). Volunteers were sent by train or ship from France to Spain, and sent to the base at Albacete. Many of them also went by themselves to Spain. The volunteers were under no contract, nor defined engagement period, which would later prove a problem.

Also, many Italians, Germans, and people from other countries joined the movement, with the idea that combat in Spain was the first step to restore democracy or advance a revolutionary cause in their own country. There were also many unemployed workers (especially from France), and adventurers. Finally, some 500 communists who had been exiled to Russia were sent to Spain (among them, experienced military leaders from the First World War like "Kléber" Stern, "Gomez" Zaisser, "Lukacs" Zalka and "Gal" Galicz, who would prove invaluable in combat).

The operation was met with enthusiasm by communists, but by anarchists with skepticism, at best. At first, the anarchists, who controlled the borders with France, were told to refuse communist volunteers, but reluctantly allowed their passage after protests. Keith Scott Watson, a journalist who fought alongside Esmond Romilly at Cerro de los Ángeles and who later “resigned” from the Thälmann Battalion, describes in his memoirs how he was detained and interrogated by Anarchist border guards before eventually being allowed into the country.[8] A group of 500 volunteers (mainly French, with a few exiled Poles and Germans) arrived in Albacete on 14 October 1936. They were met by international volunteers who had already been fighting in Spain: Germans from the Thälmann Battalion, Italians from the Centuria Gastone Sozzi and French from the Commune de Paris Battalion. Among them was the poet John Cornford, who had travelled down through France and Spain with a group of fellow intellectuals and artists including John Sommerfield, Bernard Knox and Jan Kurzke, all of whom left detailed memoirs of their battle experiences.[9]

On 30 May 1937, the Spanish liner Ciudad de Barcelona, carrying 200–250 volunteers from Marseille to Spain, was torpedoed by a Nationalist submarine off the coast of Malgrat de Mar. The ship sunk and up to 65 volunteers are estimated to have drowned.[10]

Albacete soon became the International Brigades headquarters and its main depot. It was run by a troika of Comintern heavyweights: André Marty was commander; Luigi Longo (Gallo) was Inspector-General; and Giuseppe Di Vittorio (Nicoletti) was chief political commissar.[11]

There were many Jewish volunteers amongst the brigaders - about a quarter of the total. A Jewish company was formed within the Polish battalion that was named after Naftali Botwin, a young Jewish communist killed in Poland in 1925.[12]

The French Communist Party provided uniforms for the Brigades. They were organized into mixed brigades, the basic military unit of the Republican People's Army.[13] Discipline was severe. For several weeks, the Brigades were locked in their base while their strict military training was underway.

Service

First engagements: Siege of Madrid

The Battle of Madrid was a major success for the Republic, and staved off the prospect of a rapid defeat at the hands of Francisco Franco's forces. The role of the International Brigades in this victory was generally recognized but was exaggerated by Comintern propaganda so that the outside world heard only of their victories and not those of Spanish units. So successful was such propaganda that the British Ambassador, Sir Henry Chilton, declared that there were no Spaniards in the army which had defended Madrid. The International Brigade forces that fought in Madrid arrived after another successful Republican fighting. Of the 40,000 Republican troops in the city, the foreign troops numbered less than 3,000.[14]

Even though the International Brigades did not win the battle by themselves, nor significantly change the situation, they certainly did provide an example by their determined fighting and improved the morale of the population by demonstrating the concern of other nations in the fight. Many of the older members of the International Brigades provided valuable combat experience, having fought during the First World War (Spain remained neutral in 1914–1918) and the Irish War of Independence (some had fought in the British Army while others had fought in the Irish Republican Army (IRA)).

One of the strategic positions in Madrid was the Casa de Campo. There the Nationalist troops were Moroccans, commanded by General José Enrique Varela. They were stopped by III and IV Brigades of the Spanish Republican Army.

On 9 November 1936, the XI International Brigade – comprising 1,900 men from the Edgar André Battalion, the Commune de Paris Battalion and the Dabrowski Battalion, together with a British machine-gun company — took up position at the Casa de Campo. In the evening, its commander, General Kléber, launched an assault on the Nationalist positions. This lasted for the whole night and part of the next morning. At the end of the fight, the Nationalist troops had been forced to retreat, abandoning all hopes of a direct assault on Madrid by Casa de Campo, while the XIth Brigade had lost a third of its personnel.[15]

On 13 November, the 1,550-man strong XII International Brigade, made up of the Thälmann Battalion, the Garibaldi Battalion and the André Marty Battalion, deployed. Commanded by General "Lukacs", they assaulted Nationalist positions on the high ground of Cerro de Los Angeles. As a result of language and communication problems, command issues, lack of rest, poor coordination with armored units, and insufficient artillery support, the attack failed.

On 19 November, the anarchist militias were forced to retreat, and Nationalist troops — Moroccans and Spanish Foreign Legionnaires, covered by the Nazi Condor Legion — captured a foothold in the University City. The 11th Brigade was sent to drive the Nationalists out of the University City. The battle was extremely bloody, a mix of artillery and aerial bombardment, with bayonet and grenade fights, room by room. Anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti was shot there on 19 November 1936 and died the next day. The battle in the university went on until three-quarters of the University City was under Nationalist control. Both sides then started setting up trenches and fortifications. It was then clear that any assault from either side would be far too costly; the Nationalist leaders had to renounce the idea of a direct assault on Madrid, and prepare for a siege of the capital.

On 13 December 1936, 18,000 nationalist troops attempted an attack to close the encirclement of Madrid at Guadarrama — an engagement known as the Battle of the Corunna Road. The Republicans sent in a Soviet armored unit, under General Dmitry Pavlov, and both XI and XII International Brigades. Violent combat followed, and they stopped the Nationalist advance.

An attack was then launched by the Republic on the Córdoba front. The battle ended in a form of stalemate; a communique was issued, saying: "During the day the advance continued without the loss of any territory." Poets Ralph Winston Fox and John Cornford were killed. Eventually, the Nationalists advanced, taking the hydroelectric station at El Campo. André Marty accused the commander of the Marseillaise Battalion, Gaston Delasalle, of espionage and treason and had him executed. (It is doubtful that Delasalle would have been a spy for Francisco Franco; he was denounced by his second-in-command, André Heussler, who was subsequently executed for treason during World War II by the French Resistance.)

Further Nationalist attempts after Christmas to encircle Madrid met with failure, but not without extremely violent combat. On 6 January 1937, the Thälmann Battalion arrived at Las Rozas and held its positions until it was destroyed as a fighting force. On 9 January, only 10 km had been lost to the Nationalists, when the XIII International Brigade and XIV International Brigade and the 1st British Company, arrived in Madrid. Violent Republican assaults were launched in an attempt to retake the land, with little success. On 15 January, trenches and fortifications were built by both sides, resulting in a stalemate.

The Nationalists did not take Madrid until the very end of the war, in March 1939, when they marched in unopposed. There were some pockets of resistance during the subsequent months.

Battle of Jarama

On 6 February 1937, following the fall of Málaga, the nationalists launched an attack on the Madrid–Andalusia road, south of Madrid. The Nationalists quickly advanced on the little town of Ciempozuelos, held by the XV International Brigade. was composed of the British Battalion (British Commonwealth and Irish), the Dimitrov Battalion (miscellaneous Balkan nationalities), the Sixth February Battalion (Belgians and French), the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. An independent 80-men-strong (mainly) Irish unit, known afterward as the Connolly Column, also fought. Battalions were rarely composed entirely of one nationality, rather they were, for the most part, a mix of many.

On 11 February 1937, a Nationalist brigade launched a surprise attack on the André Marty Battalion (XIV International Brigade), killing its sentries silently and crossing the Jarama. The Garibaldi Battalion stopped the advance with heavy fire. At another point, the same tactic allowed the Nationalists to move their troops across the river. On 12 February, the British Battalion, XV International Brigade took the brunt of the attack, remaining under heavy fire for seven hours. The position became known as "Suicide Hill". At the end of the day, only 225 of the 600 members of the British battalion remained. One company was captured by ruse, when Nationalists advanced among their ranks singing The Internationale.

On 17 February, the Republican Army counter attacked. On 23 and 27 February, the International Brigades were engaged, but with little success. The Lincoln Battalion was put under great pressure, with no artillery support. It suffered 120 killed and 175 wounded. Amongst the dead was the Irish poet Charles Donnelly and Leo Greene.[16]

There were heavy casualties on both sides, and although "both claimed victory ... both suffered defeats".[17] The battle resulted in a stalemate, with both sides digging in and creating elaborate trench systems. On 22 February 1937, the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee ban on foreign volunteers went into effect.

Battle of Guadalajara

After the failed assault on the Jarama, the Nationalists attempted another assault on Madrid, this time from the northeast. The objective was the town of Guadalajara, 50 km from Madrid. The whole Italian expeditionary corps — 35,000 men, with 80 battle tanks and 200 field artillery — was deployed, as Benito Mussolini wanted the victory to be credited to Italy. On 9 March 1937, the Italians made a breach in the Republican lines but did not properly exploit the advance. However, the rest of the Nationalist army was advancing, and the situation appeared critical for the Republicans. A formation drawn from the best available units of the Republican army, including the XI and XII International Brigades, was quickly assembled.

At dawn on 10 March, the Nationalists closed in, and by noon, the Garibaldi Battalion counterattacked. Some confusion arose from the fact that the sides were not aware of each other's movements, and that both sides spoke Italian; this resulted in scouts from both sides exchanging information without realizing they were enemies.[18] The Republican lines advanced and made contact with XI International Brigade. Nationalist tanks were shot at and infantry patrols came into action.

On 11 March, the Nationalist army broke the front of the Republican army. The Thälmann Battalion suffered heavy losses but succeeded in holding the Trijueque–Torija road. The Garibaldi also held its positions. On 12 March, Republican planes and tanks attacked. The Thälmann Battalion attacked Trijuete in a bayonet charge and re-took the town, capturing numerous prisoners.

Other battles

The International Brigades also saw combat in the Battle of Teruel in January 1938. The 35th International Division suffered heavily in this battle from aerial bombardment as well as shortages of food, winter clothing, and ammunition. The XIV International Brigade fought in the Battle of Ebro in July 1938, the last Republican offensive of the war.

Casualties

Existing primary sources provide conflicting information as to the number of brigadiers killed; a report of the IB Albacete staff from late March 1938 claimed 4,575 KIA,[19] an internal Soviet communication to Moscow by an NKVD major Semyon Gendin from late July 1938 claimed 3,615 KIA,[20] while the prime minister Juan Negrín in his farewell address in Barcelona of October 28, 1938, mentioned 5,000 fallen.[21]

Also, in historiography there is no agreement as to fatal casualties. One exact figure offered is 9,934; it was calculated in the mid-1970s[22] and is at times repeated until today.[23] The highest estimate identified is 15,000 KIA.[24] Many scholars prefer 10,000, also in recently published works.[25] The popular Osprey series claims there were at least 7,800 killed.[26] However, other authors provide estimates that point rather to the range from 6,100[27] to 6,500.[28] In some non-scholarly publications the number is given as 4,900.[29] The above figures include brigadiers killed in action, these who died of wounds later or those who were executed as POWs. They do not include brigadiers who were executed by their own side, the figure that some claim might have been 500;[30] they also do not include victims of accidents (self-shooting, traffic, drownings etc) or these who perished due to health problems (illness, frostbiten, poisoning etc).

The total number of casualties is given as 48,909. It includes killed, missing and wounded, though probably contains numerous duplicated cases, as one individual might have suffered wounds a few times.[31]

The ratio of KIA to all IB combatants as calculated by historians might differ even more as it depends not only on estimates as to the number of killed, but also on estimates as to the total number of volunteers. Some sources suggest the figure of 8.3%,[32] some authors claim 15%,[33] others opt for 16.7%,[34] prefer 24.7%[35] or endorse the ratio of 28.6%;[36] a single author arrived even at 33%.[37] In comparison, in shock units used by the Nationalists, though they were not entirely comparable, the ratio was 11.3% for the Carlist requetés[38] and 14.6% for the Moroccan regulares.[39] The overall percentage of killed in action in armies of both sides is estimated at some 7%.[40]

Estimates of KIA ratio for major national contingents differs enormously and often bear no reasonable relation to the overall KIA ratio, calculated for the Brigades. For the French (including French-speaking Belgians and Swiss) the figures range between 12%[41] and 18%;[42] for the Italians between 18%[43] and 20%;[44] for the British between 16%[45] and 22%;[46] for the Americans between 13%[47] and 32%;[48] for the Germans (including Austrians and German-speaking Swiss) between 22%[49] and 40%;[50] for the Yugoslavs between 35%[51] and 50%,[52] for the Canadians between 43% and 57%;[53] for the Poles (including Ukrainians, Jews, Belarusians) between 30%[54] and 62%.[55] Among smaller contingents, the KIA ratio calculated appears to be 10% for the Cubans,[56] 17% for the Czechoslovaks,[57] 18% for the Austrians,[58] 21% for the Balts (Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians),[59] 21-25% for the Swiss,[60] 31% for the Finns,[61] 13%-33% for the Greeks,[62] 23-35% for the Swedes,[63] 40% for the Danes,[64] and 44% for the Norwegians.[65]

Disbandment

In October 1938, at the height of the Battle of the Ebro, the Non-Intervention Committee demanded the withdrawal of the International Brigades.[66] The Republican government of Juan Negrín announced the decision in the League of Nations on 21 September 1938. The disbandment was part of an ill-advised effort to get the Nationalists' foreign backers to withdraw their troops and to persuade the Western democracies such as France and Britain to end their arms embargo on the Republic.

By this time there were about an estimated 10,000 foreign volunteers still serving in Spain for the Republican side, and about 50,000 foreign conscripts for the Nationalists (excluding another 30,000 Moroccans).[67] Perhaps half of the International Brigadistas were exiles or refugees from Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy or other countries, such as Hungary, which had authoritarian right-wing governments at the time. These men could not safely return home, and some were instead given honorary Spanish citizenship and integrated into Spanish units of the Popular Army. The remainder were repatriated to their own countries. The Belgian and Dutch volunteers lost their citizenship because they had served in a foreign army.[68]

Composition

Overview

The first brigades were composed mostly of French, Belgian, Italian, and German volunteers, backed by a sizeable contingent of Polish miners from Northern France and Belgium. The XIth, XIIth and XIIIth were the first brigades formed. Later, the XIVth and XVth Brigades were raised, mixing experienced soldiers with new volunteers. Smaller Brigades — the 86th, 129th and 150th - were formed in late 1937 and 1938, mostly for temporary tactical reasons.

About 32,000[3] foreigners volunteered to defend the Spanish Republic, the vast majority of them with the International Brigades. Many were veterans of World War I. Their early engagements in 1936 during the Siege of Madrid amply demonstrated their military and propaganda value.

The international volunteers were mainly socialists, communists, or others willing to accept communist authority, and a high proportion were Jewish. Some were involved in the Barcelona May Days fighting against leftist opponents of the Communists: the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, an anti-Stalinist Marxist party) and the anarchist CNT (CNT, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) and FAI (FAI, Iberian Anarchist Federation), who had strong support in Catalonia. These libertarian groups attracted fewer foreign volunteers.

To simplify communication, the battalions usually concentrated on people of the same nationality or language group. The battalions were often (formally, at least) named after inspirational people or events. From spring 1937 onwards, many battalions contained one Spanish volunteer company of about 150 men.

Later in the war, military discipline tightened and learning Spanish became mandatory. By decree of 23 September 1937, the International Brigades formally became units of the Spanish Foreign Legion.[69] This made them subject to the Spanish Code of Military Justice. However, the Spanish Foreign Legion itself sided with the Nationalists throughout the coup and the civil war.[69] The same decree also specified that non-Spanish officers in the Brigades should not exceed Spanish ones by more than 50 percent.[70]

Non-Spanish battalions

- Abraham Lincoln Battalion – from the United States and Canada, with some British, Cypriots, and Chileans from the Chilean Worker Club of New York.

- Connolly Column – a mostly Irish republican group who fought as a section of the Lincoln Battalion.

- Mickiewicz Battalion – predominantly Polish.

- André Marty Battalion – predominantly French and Belgian.

- British Battalion – mainly British but with many from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Cyprus and other Commonwealth countries.

- Checo-Balcánico Battalion – Czechoslovakian and Balkan.

- Commune de Paris Battalion – predominantly French.

- Deba Blagoiev Battalion – predominantly Bulgarian, later merged into the Đaković Battalion.

- Dimitrov Battalion – Greek, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian and Romanian (named after Georgi Dimitrov).

- Đuro Đaković Battalion – Yugoslav, Bulgarian, anarchist, named for former Yugoslav Communist Party secretary Djuro Đaković.

- Dabrowski Battalion – mostly Polish and Hungarian, also Czechoslovak, Ukrainian, Bulgarian and Palestinian Jews.

- Edgar André Battalion – mostly German, also Austrian, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, Albanian, Romanian, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Dutch.

- Español Battalion – Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, Chilean, Argentine and Bolivian.

- Figlio Battalion – mostly Italian; later merged with the Garibaldi Battalion.

- Garibaldi Battalion – raised as the Italoespañol Battalion and renamed. Mostly Italian and Spanish but contained some Albanians.

- George Washington Battalion – the second U.S. battalion. Later merged with the Lincoln Battalion, to form the Lincoln-Washington Battalion.

- Hans Beimler Battalion – mostly German; later merged with the Thälmann Battalion.

- Henri Barbusse Battalion – predominantly French.

- Henri Vuilleman Battalion – predominantly French.

- Italian Column (Matteotti Battalion) – predominantly Italian and the first international group to reach Spain.[71][72]

- Louise Michel Battalions – French-speaking, later merged with the Henri Vuillemin Battalion.

- Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion – the "Mac-Paps", predominantly Canadian.

- Marseillaise Battalion – predominantly French, commanded by George Nathan.

- Incorporated one separate British company.

- Palafox Battalion – Yugoslav, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Jewish and French.

- Naftali Botwin Company – a Jewish unit formed within the Palafox Battalion in December 1937.

- Pierre Brachet Battalion – mostly French.

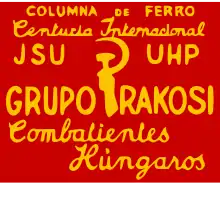

- Rakosi Battalion – mainly Hungarian, also Czechoslovaks, Ukrainians, Poles, Chinese, Mongolians and Palestinian Jews.

- Nine Nations Battalion (also known as the Sans nons and Neuf Nationalités) – French, Belgian, Italian, German, Austrian, Dutch, Danish, Swiss and Polish.

- Sixth of February Battalion – French, Belgian, Moroccan, Algerian, Libyan, Syrian, Iranian, Iraqi, Egyptian, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Filipino and Palestinian Jewish.

- Thälmann Battalion – predominantly German, named after German communist leader Ernst Thälmann.

- Tom Mann Centuria – a small, mostly British, group who operated as a section of the Thälmann Battalion.

- Thomas Masaryk Battalion: mostly Czechoslovak.

- Chapaev Battalion – composed of 21 nationalities (Ukrainian, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Bulgarian, Yugoslavian, Turkish, Italian, German, Austrian, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Belgian, French, Greek, Albanian, Dutch, Swiss, Lithuanian and Estonian).[73]

- Vaillant-Couturier Battalion – French, Belgian, Czechoslovakian, Bulgarian, Swedish, Norwegian and Danish.

- Veinte Battalion – American, British, Italian, Yugoslav and Bulgarian.

- Zwölfte Februar Battalion – mostly Austrian.

- Company De Zeven Provinciën – Dutch.

Brigadistas by country of origin

Country Estimate Notes .svg.png.webp) France

France8,962[74]–9,000[3][75] _crowned.svg.png.webp) Italy

Italy3,000[74][75]–3,350[76] .svg.png.webp) Germany

Germany3,000[3]–5,000[75] Beevor quotes 2,217 Germans and 872 Austrians.[74] .svg.png.webp) Austria

AustriaAustrian Resistance documents name 1,400 Austrians. Annexed in 1938 by Germany. .svg.png.webp) Poland

Poland500[77]–5,000[78] International historiography tends to hover around the figure of 3,000 "Poles".[3][75][74] It includes migrants from Poland but recruited in France and Belgium, who made up some 75% of the Polish contingent;[79] it also includes volunteers of Belarusian, Ukrainian and especially Jewish origin; the latter might have accounted for 45% of all volunteers classified as "Poles"[80]  United Kingdom

United Kingdom2,500–4,700[81] .svg.png.webp) United States

United States2,341[74]–2,800[75][76] .svg.png.webp) Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia1,500[3]–2,095[74] .svg.png.webp) Belgium

Belgium1,600[75]–1,722[74] .svg.png.webp) Canada

Canada1,546–2,000[75] Thomas estimates 1,000.[76]  Cuba

Cuba1,101[82][83]  Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia1,006[74]–1,500[3][75]  Argentina

Argentina740[84]  Netherlands

Netherlands628[74]–691[85]  Denmark

Denmark550 220 died. .svg.png.webp) Hungary

Hungary528[74]–1,500[3]  Sweden

Sweden500[86] Est. 799[74]–1,000[76] from Scandinavia (of whom 500 were Swedes.[86])  Romania

Romania500  Bulgaria

Bulgaria462 .svg.png.webp) Switzerland

Switzerland408[74]–800[87] .svg.png.webp) Lithuania

Lithuania300–600[88][74]  Ireland

Ireland250 Split between the British Battalion and the Lincoln Battalion which included the famed Connolly Column  Norway

Norway225 100 died.[89][90][91]  Finland

Finland225 Including 78 Finnish Americans and 73 Finnish Canadians, ca. 70 died.[92]  Estonia

Estonia200[93][74] .svg.png.webp) Greece

Greece290–400[94]  Portugal

Portugal134[74] Due to the geographic and linguistic proximity most Portuguese volunteers joined the Republican forces directly and not the International Brigades (such is the case of Emídio Guerreiro and that was the plan of the failed 1936 Naval Revolt). At the time it was estimated that about 2,000 Portuguese fought on the Republican side, spread throughout different units.[95]  Luxembourg

Luxembourg103[96] Livre historiographic d'Henri Wehenkel – D'Spueniekämfer (1997)  China

China100[97] Organised by the Chinese Communist Party, members were mostly overseas Chinese led by Xie Weijin.[98] .svg.png.webp) Mexico

Mexico90 .svg.png.webp) Cyprus

Cyprus60[94] .svg.png.webp) Australia

Australia60[99] Of whom 16 killed.[99] .svg.png.webp) Philippines

Philippines50[100][101] .svg.png.webp) Albania

Albania43 Organised in the "Garibaldi Battalion" together with Italians. They were led by the Kosovar revolutionary Asim Vokshi .svg.png.webp) Costa Rica

Costa Rica24[3]  New Zealand

New Zealand"Perhaps 20"[102] Mixed into British units Others 1,122[74]

Status after the war

_1966%252C_MiNr_1198.jpg.webp)

After the Civil War was eventually won by the Nationalists, the brigaders were initially on the "wrong side" of history, especially as most of their home countries had right-wing governments (in France, for instance, the Popular Front was not in power anymore).

However, since most of these countries soon found themselves at war with the very powers which had been supporting the Nationalists, the brigadistas gained some prestige as the first guard of the democracies, as having foreseen the danger of fascism and gone to fight it. Retrospectively, it was clear that the war in Spain was as much a precursor of the Second World War as a Spanish civil war.

Some glory therefore accrued to the volunteers (a great many of the survivors also fought during World War II), but this soon faded in the fear that it would promote communism by association.

An exception is among some left-wingers, for example many anarchists. Among these, the Brigades, or at least their leadership, are criticized for their role in suppressing the Spanish Revolution. An example of a modern work that promotes this view is Ken Loach's film Land and Freedom. A well-known contemporary account of the Spanish Civil War which also takes this view is George Orwell's book Homage to Catalonia.

East Germany

Germany was undivided until after the Second World War. At that time, the new communist state, the German Democratic Republic, began to create a national identity which was separate from and antithetical to the former Nazi Germany. The Spanish Civil War, and especially the role of the International Brigades, became a substantial part of East Germany's memorial rituals because of the substantial numbers of German communists who had served in the brigades. These showcased a commitment by many Germans to antifascism at a time when Germany and Nazism were often conflated.[103]

Canada

Survivors of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion were often investigated by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and denied employment when they returned to Canada. Some were prevented from serving in the military during the Second World War due to "political unreliability".

In 1995 a monument to veterans of the war was built near Ontario's provincial parliament.[104] On 12 February 2000, a bronze statue "The Spirit of the Republic" by sculptor Jack Harman, based on an original poster from the Spanish Republic, was placed on the grounds of the British Columbia Legislature.[105] In 2001, the few remaining Canadian veterans of the Spanish Civil War dedicated a monument to Canadian members of the International Brigades in Ottawa's Green Island Park.

Poland

In line with the 1920 legislation, Polish citizens who volunteered to the IB were automatically stripped of citizenship as individuals who without formal approval served in foreign armed forces.[106] Following republican defeat the combatants recruited in France and Belgium returned there.[107] Among the others some served in pro-Communist partisan units in the German-occupied Poland[108] and some made it to the USSR[109] and served in the pro-Communist Polish army raised there.[110]

In the Communist Poland the IB combatants – referred to as "Dąbrowszczacy" - were granted veteran rights, but their fate differed depending upon political circumstances. Following some early exaltation in 1945-1949[111] they were later approached somewhat cautiously. There were cases of assuming high positions in administration[112] and especially in security,[113] but there were also cases of deposition, arrest and prison on trumped-up charges of political conspiracy;[114] these were released in the mid-1950s.[115]

Though from the onset Polish engagement in IB was hailed as "working class taking to arms against Fascism", the most intense idolization took place between the mid-1950s and the mid-1960s, with a spate of publications, schools and streets named after "Dąbrowszczacy".[116] However, an antisemitic turn in the late 1960s again produced de-emphasizing of IB volunteers, many of whom left Poland.[117] Until the end of Communist rule the IB episode was duly acknowledged, but propaganda related was a far cry from veneration reserved for wartime Communist partisans or the USSR-raised Polish army.[118] Despite some efforts on part of IB combatants, no monument has been erected.[119]

After 1989 it was unclear whether Dąbrowszczacy were furtherly entitled to veteran privileges; the issue generated political debates until they became pointless, as almost all IB combatants had passed away.[120] Another question was about homage references, existent in public space. A state-run institution IPN declared Polish IB combatants in service of the Stalinist regime and related homage references subject to de-communisation legislation.[121] However, efficiency of purges of public space differs depending upon local political configuration and occasionally there is heated public debate ensuing.[122] Until today the role of Polish IB combatants remains a highly divisive topic; for some they are traitors and for some they are heroes.[123]

Switzerland

In Switzerland, public sympathy was high for the Republican cause, but the federal government banned all fundraising and recruiting activities a month after the start of the war as part of the country's long-standing policy of neutrality.[87] Around 800 Swiss volunteers joined the International Brigades, among them a small number of women.[87] Sixty percent of Swiss volunteers identified as communists, while the others included socialists, anarchists and antifascists.[87]

Some 170 Swiss volunteers were killed in the war.[87] The survivors were tried by military courts upon their return to Switzerland for violating the criminal prohibition on foreign military service.[87][124] The courts pronounced 420 sentences which ranged from around 2 weeks to 4 years in prison, and often also stripped the convicts of their political rights for the period of up to 5 years. In the Swiss society, traditionally highly appreciative of civic virtues, this translated to longtime stigmatization also after the penalty period expired.[125] In the judgment of Swiss historian Mauro Cerutti, volunteers were punished more harshly in Switzerland than in any other democratic country.[87]

Motions to pardon the Swiss brigaders on the account that they fought for a just cause have been repeatedly introduced in the Swiss federal parliament. A first such proposal was defeated in 1939 on neutrality grounds.[87] In 2002, Parliament again rejected a pardon of the Swiss war volunteers, with a majority arguing that they broke a law that remains in effect to this day.[126] In March 2009, Parliament adopted the third bill of pardon, retroactively rehabilitating Swiss brigades, only a handful of whom were still alive.[127] In 2000 there was a monument honoring Swiss IB combatants unveiled in Geneva; there are also numerous plaques mounted elsewhere, e.g., at the Volkshaus in Zürich.[128]

United Kingdom

On disbandment, 305 British volunteers left Spain to return home.[129] They arrived at Victoria Station in central London on 7 December and were met warmly as returning heroes by a crowd of supporters including Clement Attlee, Stafford Cripps, Willie Gallacher, Ellen Wilkinson and Will Lawther.[130]

The last surviving British member of the International Brigades, Geoffrey Servante, died in April 2019 aged 99.[131]

IBMT

The International Brigade Memorial Trust is a registered charity that handles activities around the memory of volunteers from Britain and Ireland. The group maintains a map of memorials to volunteers in the Spanish Civil War and organises yearly events to commemorate the war.

United States

In the United States, the returned volunteers were labeled "premature anti-fascists" by the FBI, denied promotion during service in the U.S. military during World War II, and pursued by Congressional committees during the Red Scare of 1947–1957.[132][133] However, threats of loss of citizenship were not carried out.

Recognition

Josep Almudéver, believed to be the last surviving veteran of the International Brigades, died on 23 May 2021 at the age of 101. Although born into a Spanish family and living in Spain at the outbreak of the conflict, he also held French citizenship and enlisted in the International Brigades to avoid age restrictions in the Spanish Republican army. He served in the CXXIX International Brigade and later fought in the Spanish Maquis, and after the war lived in exile in France.[134]

Spain

On 26 January 1996, the Spanish government gave Spanish citizenship to the 600 or so remaining Brigadistas, fulfilling a promise made by Prime Minister Juan Negrín in 1938.

France

In 1996, Jacques Chirac, then French President, granted the former French members of the International Brigades the legal status of former service personnel ("ancient combatants") following the request of two French communist Members of Parliament, Lefort and Asensi, both children of volunteers. Before 1996, the same request was turned down several times including by François Mitterrand, the former Socialist President.

Symbolism and heraldry

The International Brigades were inheritors of a socialist aesthetic. The flags featured the colors of the Spanish Republic: red, yellow and purple, often along with socialist symbols (red flags, hammer and sickle, fist). The emblem of the brigades themselves was the three-pointed red star, which is often featured.

See also

References

Footnotes

- Grasmeder, Elizabeth M.F. (2021). "Leaning on Legionnaires: Why Modern States Recruit Foreign Soldiers". International Security. 46 (1): 147–195. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00411. S2CID 236094319. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- "Reportaje | La última brigadista". EL PAÍS (in Spanish). 11 December 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- Thomas (2003), pp. 941–945.

- Rein, Raanan (2020). "De Moisés Ville a Madrid: Los argentinos judíos y la solidaridad con el bando republicano durante la Guerra Civil Española". Cuadernos de Historia de España. Buenos Aires: UBA (87): 13–36. doi:10.34096/che.n87.9046.

- Orwell, George. Homage to Catalonia. Penguin Group. Re-print, 2000. Work: Autobiographical account of the author's participation in the Spanish Civil War. ISBN 978 0 141 18305 3

- Beevor 1999, p. 124

- "Third International | association of political parties". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Single to Spain by Keith Scott Watson, first published 1937, republished "The Clapton Press". 20 January 2022. 2022. ISBN 978-1-913693-11-4

- The Good Comrade: Memoirs of an International Brigader by Jan Kurzke "The Clapton Press". 4 May 2021. 2021. ISBN 978-1-913693-06-0

- "The Sinking of the "Ciudad de Barcelona", 30th May 1937". Ciudad de Barcelona. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Thomas 2003, p. 443

- Graham, Helen (2005). The Spanish Civil War : a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-19-280377-8. OCLC 57243230.

- Orden, circular, creando un Comisariado general de Guerra con la misión que se indica (PDF). Vol. Año CCLXXV Tomo IV, Núm. 290. Gaceta de Madrid: diario oficial de la República. 16 October 1936. p. 355.

- Beevor (1982), p 137; Anderson (2003), p 59.

- Boadilla by Esmond Romilly, The Clapton Press London, 2018. ISBN 978-1999654306

- McInerney, Michael (December 1979). "The Enigma of Frank Ryan part 1" (PDF). Old Limerick Journal. 1. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Thomas 2003, p. 579

- Beevor 1999, p. 158

- Giles Tremmet, The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War, London 2021, ISBN 9781526644541, p. 7

- report of Semyon Gendin РГВА, ф. 33987, оп. 3, д. 1149, л. 260—269 [retrieved July 11, 2022]

- Daniel Pastor García, Antonio R. Celada, The Victors Write History, the Vanquished Literature: Myth, Distortion and Truth in the XV Brigade, [in:] Susana Belenguer, Ciaran Cosgrove, James Whiston (eds.), Living the Death of Democracy in Spain: The Civil War and Its Aftermath, London 2017, ISBN 9781317525431, p. 312

- Andreu Castells, Les Brigades Internacionales de la Guerra España, Barcelona 1974, p. 383

- Bruno Mugnai, Foreign volunteers and International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Firenze 2019, ISBN 9788893274210, p. 66, Carlos Engel, Azul y rojo: imágenes de la Guerra Civil Española, Madrid 1999, ISBN 9788493071301. p. 78

- "some raise the figure to 15,000, which seems to be entirely unfounded", Pastor García, Celada 2017, p. 312

- see e.g. Julian Casanova, The Spanish Civil War, London 2019, ISBN 9781350127586, p. 96, quoting Michel Lefèbvre, Rémi Skoutelsky, Les brigades internationales, Paris 2009, ISBN 9782376220718

- Ken Bradley, The International Brigades in Spain, London 1994, ISBN 18553323672, p. 7

- “of the total of 41,000 volunteers” there were “approximately 15 percent of the volunteers killed”, Stanley G. Payne, The Spanish Civil War, Cambridge 2012, ISBN 9780521174701, pp. 153, 157

- Eugeniusz Kozłowski, Brygady Międzynarodowe w obronie republiki hiszpańskiej, [w:] Dąbrowszczacy w wojnie hiszpańskiej 1936-1939, Warszawa 1989, s. 81

- out of 59,380 (8,3%), Spartacus International website [retrieved July 11, 2022]

- Andre Marty claimed he personally shot 500 men for cowardice, indiscipline and desertion, but the figure is doubted, Antony Beevor, Battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, London 2012, ISBN 9781780224534 p. 161

- Engel 1999, p. 78

- Spartacus International website [retrieved July 11, 2022]

- Payne 2012, p. 157

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- a "composite index", Jackson 1994, p. 106

- Casanova 2019, p. 96

- "An estimated third of all international volunteers were killed", Andy Durgan, Freedom fighters or Comintern army? The International Brigades in Spain, [in:] Marxist.org service 1999 [retrieved July 11, 2022]

- Payne 2012, s. 184

- 11,500 out of 78,500), Stephanie Wright, Glorious Brothers, Unsuitable Lovers: Moroccan Veterans, Spanish Women, and the Mechanisms of Francoist Paternalism, [in:] Journal of Contemporary History 55/1 (2020), p. 53

- “the rate of loss was about average for the two contending armies (which averaged approximately 7 percent fatalities) and was exceeded only by that of special units, such as the International Brigades, about 15 percent of whose effectives were killed” Stanley G. Payne, The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism, New Haven/London 2004, ISBN 9780300178326, p. 153

- L’epopée de L’espagne, Paris 1957, p. 80, referred after Michael W. Jackson, Fallen Sparrows: The International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, New York 1994, ISBN 9780871692122, s. 106

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- Palmiro Togliatti, Le Parti Communiste Italien, Paris 1961, p. 102, referred after Jackson 1994, p. 106

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- International Brigade Memorial Trust website [retrieved July 11, 2022]; the figure of 20% in Neal Wood, Communism and British Intellectuals, London 1959, p. 56, referred after Jackson p. 106

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- Edwin Rolfe, The Lincoln Battalion, New York 1939, p. 7, referred after Jackson 1994, p. 106

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- Alfred Kantorowicz, Spanische Tagebuch, Berlin 1948, p. 15, referred after Jackson 1994, p. 106

- Castells 1974, p. 383

- Tito speaks, [in:] Life 28.04.1952, referred after Jackson 1994, p. 106

- Monument to Spanish Civil War's Mac-Paps veterans unveiled, [in:] Archive News site [retrieved July 11, 2022]

- Bartłomiej Różycki, Polska ludowa wobec Hiszpanii frankistowskiej i hiszpańskiej transformacji ustrojowej, Warszawa 2015, ISBN 9788376297651, p. 146, Jacek Pietrzak, Polscy uczestnicy hiszpańskiej wojny domowej, [w:] Acta Universitatis Lodzensis. Folia Historica 97 (2016), p. 65

- allegedly 3,500 out of 5,200, Lech Wyszczelski, Wysiłek organizacyjny i bojowy dąbrowszczaków w wojnie hiszpańskiej w latach 1936-1939, [w:] Dąbrowszczacy w wojnie hiszpańskiej 1936-1939, Warszawa 1989, s. 98

- "111 muertos para 1 101 combatientes", "Los voluntarios cubanos en la GCE". Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Jiří Nedvěd, Českoslovenští dobrovolníci, mezinárodní brigády a občanská válka ve Španělsku v letech 1936 - 1939 [MA dissertation accepted at the Charles University in Prague], Praha 2008, claims that out of 2170 volunteers from Czechoslovakia (p. 90) there were 370 KIA, POW and MIA (p. 144)

- "De los 1.400 voluntarios austríacos, unos 250 murieron en diferentes frentes de la guerra", Fran Gálvez, Austria recuerda a sus brigadistas que lucharon en la Guerra Civil de España, [in:] La Vanguardia 13.10.2016

- 190 out of 892 voluntyeers, referred after Ignacio de la Torre Sanclemente, The role of the Baltics in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War (MA thesis University of Latvia), Riga 2015, p. 35, p. 35

- out of some 800 Swiss volunteers there were 170 KIA, Daniele Mariani, No pardon for Spanish civil war helpers, [in:] SwissInfo 27.02.2008. According to another work out of 815 Swiss volunteers there were 185-200 dead (23-25%), Manuel Alberto Ramón Carrión, Los voluntarios suizos en las Brigadas Internacionales, [in:] Hispania Nova 19 (2020), pp. 233, 243-244

- 70 KIA out of 225 volunteers, Jyrki Juusela, Suomalaiset Espanjan sisällissodassa, Helsinki 2003, ISBN 9789517963244, referred after de la Torre 2015, p. 35

- including Cypriots; there are 53 KIA known by name, though the number is believed to be around 100 KIA, all out of 300 or 400 volunteers, efor. "The Greek antifascist volunteers in the Spanish Civil War". EAGAINST.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- estimates as to irrecoverable losses for some 500-men-strong Swedish contingent, Fernando Camacho Padilla, Ana de la Asunción Criado, El papel de Suecia en la guerra civil española (1936-1939), [in:] Les Cahiers de Framespa [online] 27 (2018)

- 220 dead out of 550, Michel Lefebvre-Peña, Rémi Skoutelsky, Les brigades internationales. Images retrouvées, Paris 2003, ISBN 9782020523905, referred after de la Torre 2015, p. 35

- 100 KIA out of 225 volunteers, Jo Stein Moen, Rolf Moen Sæther, Tusen dager: Norge og den spanske borgerkrigen 1936-1939, Oslo 2009, ISBN 9788205393516, referred after de la Torre 2015, p. 35

- Lorenzo Peña, eroj@eroj.org. "Mensaje de de Despedida a Los voluntarios de las Brigadas Internacionales y otros discursos de La Pasionaria". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Exit - Time, Monday, 3 October 1938

- Orwell (1938).

- Beevor 2006, p. 309

- Castells (1974), pp. 258–259.

- Sachar, Howard M. (2013). Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8041-5053-8.

- Pugliese, Stanislao G. (1999). Carlo Rosselli: Socialist Heretic and Antifascist Exile. Harvard University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-674-00053-7.

- Kantorowicz (1948)

- Lefebvre (2003), p. 16. Quoted by Beevor (2006), p. 468.

- Quoted in Alvarez (1996).

- Thomas (1961), pp. 634–639.

- the number of volunteers arriving directly from Poland is estimated at 500, 600, 800 or at best 1,200, Cieplewicz, Mieczysław (1990), Zarys dziejów wojskowości polskiej w latach 1864-1939, Warszawa, p. 734, Pietrzak, Jacek (2016), Polscy uczestnicy hiszpańskiej wojny domowej, [in:] Acta Universitatis Lodzensis 97, p. 65

- the figure of 5,000 volunteers "from Poland" at times appears in general Polish public discourse or in semi-scientific publications, compare "all in all, in Spain there were some 5,000 volunteers from Poland", Szymowski, Leszek (2018), Wojna domowa w Hiszpanii: pomocnicy spod czerwonej gwiazdy, [in:] Rzeczpospolita 28.07.2018 [retrieved 20 December 2019], "there were some 5,000 volunteers from Poland during the Civil War in Spain", Siek, Magdalena (2010), Wojna domowa w Hiszpanii. Wstęp Archived 18 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Warszawa, p. 2. Older Polish prints, often intended for propaganda purposes, when quoting the 5,000 figure referred more vaguely to "Polish volunteers", "Polish citizens" or "Poles", see e.g. "over 5,000 Polish volunteers", Dąbrowszczacy. Tow. Eugeniusz Szyr o udziale Polaków w antyfaszystowskiej walce ludu hiszpańskiego, [in:] Trybuna Ludu 21.10.1966, p. 3, quoted after Różycki, Bartłomiej (2013), Dąbrowszczacy i pamięć o hiszpańskiej wojnie domowej, [in:] Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość 12/1, p. 186. In present-day Polish historiography the figure of 5,000 "Polish volunteers" is relatively rare, but it does appear, see e.g. "it is accepted that they were ca. 4,5-5,000", Pietrzak, Jacek (2016), Polscy uczestnicy hiszpańskiej wojny domowej, [in:] Acta Universitatis Lodzensis 97, p. 6

- Pietrzak, Jacek (2016), Polscy uczestnicy hiszpańskiej wojny domowej, Acta Universitatis Lodzensis 97, p. 65

- Jews, Siek, Magdalena (2010), Wojna domowa w Hiszpanii. Wstęp Archived 18 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Warszawa, p. 2

- Richard Baxell, British Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, 2012

- "Los voluntarios cubanos en la GCE". Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "New book on Cubans in SCW". Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "Voluntarios Argentinos en la Brigada XV Abraham Lincoln". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Lodewijk Petram & Samuël Kruizinga, De oorlog tegemoet, (2020) p.262.

- Thomas 2003, p. 943

- Mariani, Daniele (27 February 2008). "No pardon for Spanish civil war helpers". Swissinfo.

- "Lietuviai Ispanijos pilietiniame kare – Praeities paslaptys". www.praeitiespaslaptys.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Moen, Jo Stein og Sæther, Rolf: Tusen dager – Norge og den spanske borgerkrigen 1936-1939, Gyldendal 2009, ISBN 978-82-05-39351-6

- "frifagbevegelse.no - Nyheter fra arbeidslivet og fagbevegelsen". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "Tusen dager". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Juusela, Jyrki: Suomalaiset Espanjan sisällissodassa, Atena Kustannus 2003, ISBN 951-796-324-6

- Kuuli, (1965).

- efor. "The Greek antifascist volunteers in the Spanish Civil War". EAGAINST.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- https://www.esquerda.net/artigo/jaime-cortesao-e-os-antifascistas-portugueses-na-espanha-republicana-e-na-guerra-civil/72547 (in Portuguese)

- Henri Wehenkel, "D’Spueniekämpfer – volontaires de la Guerre d’Espagne partis du Luxembourg", CDMH, Dudelange 1997 p. 14

- "朱德等赠给国际纵队中国支队的锦旗". National Museum of China. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- "战斗在西班牙反法西斯前线的中国支队". Luobinghui. 30 March 2005. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008.

- "Serving in Spain". Australia & the Spanish Civil War: Activism & Reaction. Australian National University. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Spanish Civil War - Filipino Involement [sic]". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "SPANISH FALANGE IN THE PHILIPPINES, 1936-1945". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "The Spanish Civil War". New Zealand History. New Zealand Government. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- The Cult of the Spanish Civil War in East Germany (abstract) - Krammer, Arnold, Texas A&M University. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- Kastner, Susan (4 June 1995). "Unsung Canadian soldiers honored . . .at last". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012.

- ""Mac-Pap" Monument Unveiling". workingTV. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- Różycki, Bartłomiej (2015), Polska Ludowa wobec Hiszpanii frankistowskiej i hiszpańskiej transformacji ustrojowej, Warszawa, p. 149

- Różycki 2015, p. 148

- individual paths from internment camps to occupied Poland differed, e.g. in 1940 some ex-combatants volunteered to German labor units, recruited in occupied France and deployed in the East; some fought in the Polish army in France or in the French army and were taken prisoner by the Germans; some were parachuted from the USSR

- in few cases some Polish IB volunteers were recalled from Spain to the USSR, mostly to be executed; this was the case e.g. of Kazimierz Cichowski and Gustaw Reicher

- usually they remained in French internment camps in Algeria until liberated by the Americans; in 1942-1943 from Africa via Middle East they made it to the USSR

- in 1945-1949 the IB combatants were united in an own ex-combatant organisation, Związek Uczestników Walk o Wolność Hiszpanii; later it was amalgamanted into a general ex-combatant organisation, Różycki 2015, pp. 150-151. The group enjoyed support of Karol Świerczewski, in Spain a career Soviet commander who during few strings commanded IB units, Różycki 2015, p. 152

- the highest-ranking IB combatant was Eugeniusz Szyr, who served as deputy prime minister in 1959-1972, Pietrzak, Jacek (2016), Polscy uczestnicy hiszpańskiej wojny domowej, [in:] Acta Universitatis Lodzensis 97, p. 78

- Mieczysław Mietkowski, Grzegorz Korczyński, Franciszek Księżarczyk, Wacław Komar, Pietrzak 2016, p. 78

- Grzegorz Korczyński, Wacław Komar, Stanisław Flato, Michał Bron, Wiktor Taubenfliegel, Pietrzak 2016, p. 78

- Różycki 2015, p. 186

- Różycki 2015, pp. 186-187

- Różycki 2015, pp. 187-188. The best-known are Emanuel Mink, Michał Bron, Wiktor Taubenfligel, Józef Kutin, Eugenia Łozińska, Aleksander Szurek, Artur Kowalski and Ludwik Zagórski

- Różycki 2015, pp. 188-190

- except a commemorative stone in the Powązki military cemetery

- the legislation adopted in 1991 declared that veterans are individuals who "actively participated in the struggles for Poland's independence and sovereignty"; the veteran status allowed a number of privileges, see the official site of Urząd do Spraw Kombatantów i Osób Represjonowanych

- "Byli realizatorami polityki stalinowskiej na Półwyspie Iberyjskim", Nazwy do zmiany: Dąbrowszczaków, [in:] IPN service [retrieved 20 June 2022]

- in some cases street names have been changed but restored later, for Warsaw see Jarosław Osowski, Koniec dekomunizacji w Warszawie, [in:] Gazeta Wyborcza 10.04.2019 [retrieved 20 June 2022]. In some cases there was conflict between regional and municipal authorities, one trying to overrule another

- Opioła, Wojciech (2016), Hiszpańska wojna domowa w polskich dyskursach politycznych. Analiza publicystyki 1936–2015, Opole, pp. 238-245, Pietrzak 2016, p. 80

- Swiss Military Penal Code , SR/RS 321.0 (E·D·F·I), art. 94 (E·D·F·I)

- Piotr Bednarz, Szwajcarscy ochotnicy w Brygadach Międzynarodowych w Hiszpanii (1936–1939), [in:] Acta Universitatis Lodzensis 97 (2016), p. 139

- Report of the Judicial Committee of the National Council, Off. J. 2002 pp. 7786 et seq.

- "Parliament pardons Spanish Civil War fighters". Swissinfo. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Bednarz 2016, p. 140

- Baxell, Richard (6 September 2012). Unlikely Warriors: The British in the Spanish Civil War and the Struggle Against Fascism (Hardcover). London: Aurum Press Limited. pp. 400. ISBN 978-1845136970.

- UK: WAR: INTERNATIONAL BRIGADE RETURN FROM FIGHTING IN SPAIN (1938), retrieved 9 August 2023

- "Farewell to Geoffrey Servante, our last man standing - International Brigade Memorial Trust". www.international-brigades.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Premature antifascists and the Post-war world Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives — Bill Susman Lecture Series. King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center at New York University, 1998. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Bernard Knox, Premature Anti-Fascist Archived 8 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, reprinted from The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives — Bill Susman Lecture Series. King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center — New York University, 1998. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- "Josep Almudéver died on May 23rd". The Economist. 5 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

Sources

- Alvarez, Santiago. (in Spanish) Historia politica y militar de las brigadas internacionales Madrid: Compañía Literaria, 1996.

- Anderson, James W. The Spanish Civil War: A History and Reference Guide. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-313-32274-7

- Baxell, Richard (6 September 2012). Unlikely Warriors: The British in the Spanish Civil War and the Struggle Against Fascism (hardcover). London, England: Aurum Press Limited. p. 400. ISBN 978-1845136970.

- Beevor, Antony (1999) [1982]. The Spanish Civil War. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35281-4.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War 1936 - 1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- Bradley, Ken. International Brigades in Spain 1936-39 with Mike Chappell (Illustrator) Published by Elite. ISBN 978-1855323674.

- Brome, Vincent. The International Brigades: Spain 1936–1939. London: Heinemann, 1965.

- Castells, Andreu. (in Spanish) Las brigadas internacionales en la guerra de España. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel, 1974.

- Copeman, Fred (1948). Reason in Revolt. London: Blandford Press, 1948.

- Eby, Cecil. Comrades and Commissars. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-271-02910-8

- Gurney, Jason (1974) Crusade in Spain. London: Faber, 1974. ISBN 978-0-571-10310-2

- Kantorowicz, Alfred (1938, 1948), Spanisches Tagebuch, Madrid (1938), Berlin (1948).

- Kuuli, O; Riis, V; Utt, O; (editors) (1965) (in Estonian) Hispaania tules. Mälestusi ja dokumente fašismivastasest võitlusest Hispaanias 1936.-1939. aastal. Tallinn: Eesti raamat.

- Lefebvre, Michel; Skoutelsky, Rémi. (in Spanish) Las brigadas internacionales. Barcelona: Lunwerg Editores (2003). ISBN 84-7782-000-7

- Marco, Jorge and Thomas, Maria, "'Mucho malo for fascisti': Languages and Transnational Soldiers in the Spanish Civil War", War & Society, 38-2 (2019)

- Marco, Jorge, "The Antifascist Tower of Babel: Language Barriers in Civil-War Spain", The Volunteer, December (2019)

- Marco, Jorge, "Transnational Soldiers and Guerrilla Warfare from the Spanish Civil War to the Second World War", War i History (2018)

- Marco, Jorge and Anderson, Peter, "Legitimacy by proxy:searching for a usable past through the International Brigades in Spain’s Post-Franco democracy, 1975-2015", Journal of Modern European History, 14-3 (2016)

- Orwell, George. [1938] A Homage to Catalonia. London: Penguin Books, 1969. (New edition) ISBN 978-0-14-001699-4

- Thomas, Hugh. (1961) The Spanish Civil War. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1961.

- Thomas, Hugh (2003). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101161-5.

- Giles Tremlett. (2020) The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War, Bloomsbury, 2020 ISBN 978-1-4088-5398-6

- Wainwright, John, L. (2011) The Last to Fall: the Life and Letters of Ivor Hickman - an International Brigader in Spain. Southampton: Hatchet Green Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9568372-1-9

- "Spanish Civil War 'drew 4,000 Britons' to fight fascism". BBC News. London, England. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.