Georgi Dimitrov

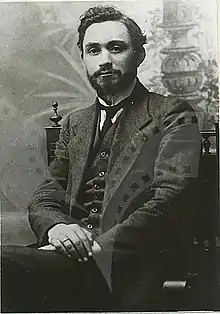

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (/dɪˈmiːtrɒf/;[1] Bulgarian: Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов) also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (Russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian communist politician who served as General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party from 1946 to 1949. From 1935 to 1943, he was the General Secretary of the Communist International.

Georgi Dimitrov | |

|---|---|

| Георги Димитров | |

| |

| General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party | |

| In office 27 December 1948 – 2 July 1949 | |

| Succeeded by | Valko Chervenkov |

| 32nd Prime Minister of Bulgaria 2nd Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Bulgaria | |

| In office 23 November 1946 – 2 July 1949 | |

| Preceded by | Kimon Georgiev |

| Succeeded by | Vasil Kolarov |

| Head of the International Policy Department of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 27 December 1943 – 29 December 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Post established |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Suslov |

| General Secretary of the Executive Committee of the Communist International | |

| In office 1935–1943 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov

(Bulgarian: Георги Димитров Михайлов) 18 June 1882 Kovachevtsi, Principality of Bulgaria |

| Died | 2 July 1949 (aged 67) Barvikha, RSFSR, USSR |

| Political party | BCP |

| Other political affiliations | BRSDP (1902–1903) BSDWP-Narrow Socialists (1903–1919) |

| Spouse(s) | Ljubica Ivošević (1906–1933) Roza Yulievna (until 1949) |

| Profession | typesetter, revolutionary, politician |

| Part of a series on |

| Communism |

|---|

|

|

|

Born in western Bulgaria, Dimitrov worked as a printer and trade unionist during his youth. He was elected to the Bulgarian parliament as a socialist during the First World War and campaigned against the country's involvement, which led to his brief imprisonment for sedition. In 1919, he helped found the Bulgarian Communist Party, and two years later he moved to the Soviet Union and was elected to the executive committee of Profintern. In 1923, Dimitrov led a failed communist uprising against the government of Aleksandar Tsankov and was subsequently forced into exile. He lived in the Soviet Union until 1929, when he relocated to Germany and became head of the Comintern operations in central Europe.

Dimitrov rose to international prominence in the aftermath of the Reichstag fire trial. Accused of plotting the arson, he refused counsel and mounted an eloquent defence against his Nazi accusers, in particular Hermann Göring, ultimately winning acquittal. After the trial he relocated to Moscow and was elected head of Comintern.

In 1946, Dimitrov returned to Bulgaria after 22 years in exile and was elected prime minister of the newly founded People's Republic of Bulgaria. He negotiated with Josip Broz Tito to create a federation of Southern Slavs, which led to the 1947 Bled accord. The plan ultimately fell apart over differences regarding the future of the join country as well as the Macedonian question, and was completely abandoned following the fallout between Stalin and Tito. Dimitrov died after a short illness in 1949 in Barvikha near Moscow. His embalmed body was housed in the Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum in Sofia until its removal in 1990; the mausoleum was demolished in 1999.

Early life

Dimitrov was born in Kovachevtsi in present-day Pernik Province, the first of eight children, to refugee parents from Ottoman Macedonia (a mother from Bansko and a father from Razlog). His father was a rural craftsman, forced by industrialisation to become a factory worker. His mother, Parashkeva Doseva, was a Protestant Christian, and his family is sometimes described as Protestant.[2] The family moved to Radomir and then to Sofia.[3] One of Georgi's brothers, Nikola, moved to Russia, joined the Bolsheviks in Odessa until he was arrested in 1908 and exiled to Siberia, where he died in 1916.[4] Another brother, Konstantin, became a trade union leader but was killed in the First Balkan War in 1912. One of his sisters, Lena, married a future communist leader, Valko Chervenkov.

Dimitrov was sent to Sunday school by his mother, who wanted him to be a pastor, but was expelled at the age of 12, and trained as a compositor,[4] and became active in the labor movement in the Bulgarian capital, and was an active trade union member from the age of 15. In 1900, he became secretary of the Sofia branch of the printers' union.

Career

Dimitrov joined the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers' Party in 1902, and in 1903 followed Dimitar Blagoev and his wing, as it formed the Social Democratic Labour Party of Bulgaria ("The Narrow Party", or tesniaks). This party became the Bulgarian Communist Party in 1919, when it affiliated to Bolshevism and the Comintern. From 1904 to 1923, he was Secretary of the General Trade Unions Federation, which the Narrows controlled.

In 1911, he spent a month in prison for libeling an official of the rival Free Federation of Trade Unions, whom he accused of strike breaking. In 1915 (during World War I) he was elected to the Bulgarian Parliament and opposed the voting of a new war credit. In summer 1917, after he intervened in defence of wounded soldiers who were being ordered by an officer to clear out of a first class railway carriage, he was charged with 'incitement to mutiny, stripped of his parliamentary immunity and was imprisoned on 29 August 1918.[5] Released in 1919, he went underground, and made two failed attempts to visit Russia, finally reaching Moscow in February 1921. He returned to Bulgaria later in 1921 but returned to Moscow and was elected in December 1922 to the executive of Profintern, the communist trade union international.

In June 1923, when Prime Minister Aleksandar Stamboliyski was deposed through a coup d'état, Dimitrov and Khristo Kabakchiev, the leading communists in Bulgaria at that time, resolved not to take sides,[6] a decision condemned by Comintern as a "political capitulation" brought on by the party's "dogmatic-doctrinaire approach".[7] After Vasil Kolarov had been sent from Moscow to impose a change in the party line, Dimitrov accepted Comintern's authority, and in September 1923 led, alongside Kolarov, the failed uprising, against the regime of against Aleksandar Tsankov, which cost the lives of possibly five thousand communist supporters during the fighting and the reprisals that followed. Despite its failure, the attempt was approved by Comintern, and secured the positions of Kolarov and Dimitrov – who escaped via Yugoslavia to Vienna – as the joint leaders of the Bulgarian CP.

In the aftermath the St Nedelya Church, a terrorist bomb attack carried out by communists, Dimitrov was tried in absentia in May 1926 and sentenced to death, although he had not approved the attack, and his only surviving brother, Todor, was arrested and killed by royal police in 1925.[4] Under pseudonyms, he lived in the Soviet Union until 1929, when he was ousted from his leadership role in the Bulgarian communist party by a faction of younger, more left wing activists,[6] and was relocated to Germany, where he was given charge of the Central European section of the Comintern. In 1932, Dimitrov was appointed Secretary General of the World Committee Against War and Fascism, replacing Willi Münzenberg.[8]

Leipzig trial

Dimitrov was based in Berlin when the Nazis came to power, and was arrested on 9 March 1933 on the evidence of a waiter who claimed to have seen "three Russians" (in reality, Dimitrov and two other Bulgarians, Vasil Tanev, and Blagoy Popov, both of whom were members of the faction that had supplanted Dimitrov in the Bulgarian Communist Party)[6] talking in a cafe with Marinus van der Lubbe, who would later be accused of setting the Reichstag on fire by the Nazis. During the Leipzig trial, Dimitrov famously decided to refuse counsel and instead defend himself against his Nazi accusers, primarily Hermann Göring, using the trial as an opportunity to defend the ideology of Communism. Explaining why he chose to speak in his own defense, Dimitrov said:

I admit that my tone is hard and grim. The struggle of my life has always been hard and grim. My tone is frank and open. I am used to calling a spade a spade. I am no lawyer appearing before this court in the mere way of his profession. I am defending myself, an accused Communist. I am defending my political honor, my honor as a revolutionary. I am defending my Communist ideology, my ideals. I am defending the content and significance of my whole life. For these reasons every word which I say in this court is a part of me, each phrase is the expression of my deep indignation against the unjust accusation, against the putting of this anti-Communist crime, the burning of the Reichstag, to the account of the Communists.[9]

Dimitrov's calm conduct of his defence and the accusations he directed at his prosecutors won him world renown.[10] On August 24, 1942, The Milwaukee Journal declared that in the Leipzig Trial, Dimitrov displayed "the most magnificent exhibition of moral courage ever shown anywhere."[11] In Europe, a popular saying spread across the Continent: "There is only one brave man in Germany, and he is a Bulgarian."[12] Dimitrov, Tanev, and Popov were acquitted. Two months later, on 23 December, the USSR secured the release of the three Bulgarians, who were granted Soviet citizenship.

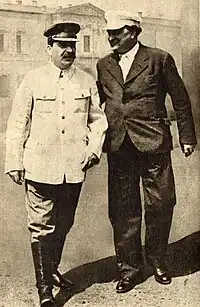

Head of Comintern

When Dimitrov arrived in Moscow, on 27 February 1934, he was encouraged by Joseph Stalin to end the practice of denouncing Social Democrats as 'social fascists', practically indistinguishable from actual fascists, and to promote united front tactics against Fascism. In April, as his fame grew in the wake of the Leipzig Trial, he was appointed a member of the Executive of Comintern and of its political secretariat, in charge of the Anglo-American and Central European sections. He was being positioned to take control of the Comintern from the Old Bolsheviks Iosif Pyatnitsky and Wilhelm Knorin, who had controlled it since 1923. Dimitrov was chosen by Stalin to be the head of the Comintern in 1934. Tzvetan Todorov says, "He became part of the Soviet leader's inner circle."[13] He was the dominant presence at the 7th Comintern Congress, in July–August 1935, at which he was elected General Secretary of Comintern.

During the Great Purge, Dimitrov knew about the mass arrests, but did almost nothing. In November 1937, he was told by Stalin to lure Willi Münzenberg to the USSR so that he could be arrested, but did not object. Similarly, he noted in his diary when Julian Leszczyński, Henryk Walecki, and several members of his staff were arrested, but again did nothing, though he did raise questions when the NKVD representative in Comintern, Mikhail Trilisser, was arrested.[14]

Leader of Bulgaria

In 1946, Dimitrov returned to Bulgaria after 22 years in exile and became leader of the Communist party there. After the founding of the People's Republic of Bulgaria in 1946, Dimitrov succeeded Kimon Georgiev as Prime Minister, while keeping his Soviet Union citizenship. Dimitrov started negotiating with Josip Broz Tito on the creation of a Federation of the Southern Slavs, which had been underway since November 1944 between the Bulgarian and Yugoslav Communist leaderships.[15] The idea was based on the idea that Yugoslavia and Bulgaria were the only two homelands of the Southern Slavs, separated from the rest of the Slavic world. The idea eventually resulted in the 1947 Bled accord, signed by Dimitrov and Tito, which called for abandoning frontier travel barriers, arranging for a future customs union, and Yugoslavia's unilateral forgiveness of Bulgarian war reparations. The preliminary plan for the federation included the incorporation of the Blagoevgrad Region ("Pirin Macedonia") into the People's Republic of Macedonia and the return of the Western Outlands from Serbia to Bulgaria. In anticipation of this, Bulgaria accepted teachers from Yugoslavia who started to teach the newly codified Macedonian language in the schools in Pirin Macedonia and issued the order that the Bulgarians of the Blagoevgrad Region should claim а Macedonian identity.[16]

However, differences soon emerged between Tito and Dimitrov with regard to both the future joint country and the Macedonian question. Whereas Dimitrov envisaged a state where Yugoslavia and Bulgaria would be placed on an equal footing and Macedonia would be more or less attached to Bulgaria, Tito saw Bulgaria as a seventh republic in an enlarged Yugoslavia tightly ruled from Belgrade.[17] Their differences also extended to the national character of the Macedonians; whereas Dimitrov considered them to be an offshoot of the Bulgarians,[18] Tito regarded them as an independent nation which had nothing to do whatsoever with the Bulgarians.[19] The initial tolerance for the Macedonization of Pirin Macedonia gradually grew into outright alarm.

By January 1948, Tito's plans to annex Bulgaria and Albania had become an obstacle to policy of the Cominform and the other Eastern Bloc countries.[15] In December 1947, Enver Hoxha and an Albanian delegation were invited to Bulgaria. During their meeting, Dimitrov told Enver Hoxha, knowing about the subversive activity of Koçi Xoxe and other pro-Yugoslav Albanian officials: "Look here, Comrade Enver, keep the Party pure! Let it be revolutionary, proletarian and everything will go well with you!"[20]

After the initial rupture, Stalin invited Tito and Dimitrov to Moscow regarding the recent incident. Dimitrov accepted the invitation, but Tito refused, and sent Edvard Kardelj, his close associate, instead.[15] The resulting fall-out between Stalin and Tito in 1948 gave the Bulgarian Government an eagerly-awaited opportunity of denouncing Yugoslav policy in Macedonia as expansionistic and of revising its policy on the Macedonian question.[21] The ideas of a Balkan Federation and a United Macedonia were abandoned, the Macedonian teachers were expelled and teaching of Macedonian throughout the province was discontinued. At the 5th Congress of the Bulgarian Workers' Party (Communists), Dimitrov accused Tito of "nationalism" and hostility towards the internationalist communists, specifically the Soviet Union.[22] Despite the fallout, Yugoslavia did not reverse its position on renouncing Bulgarian war reparations, as defined in the 1947 Bled accord.

Personal life

In 1906, Dimitrov married his first wife, Serbian emigrant milliner, writer and socialist Ljubica Ivošević, with whom he lived until her death in 1933.[3] While in the Soviet Union, Dimitrov married his second wife, the Czech-born Roza Yulievna Fleishmann (1896–1958), who gave birth to his only son, Mitya, in 1936. The boy died at age seven of diphtheria. While Mitya was alive, Dimitrov adopted Fani, a daughter of Wang Ming, the acting General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 1931.[3][23] He and his wife adopted another child, Boiko Dimitrov, born 1941.

Death

Dimitrov died on 2 July 1949 in the Barvikha sanatorium near Moscow. The speculation[15][24] that he had been poisoned has never been confirmed, although his health seemed to deteriorate quite abruptly. The supporters of the poisoning theory claim that Stalin did not like the "Balkan Federation" idea of Dimitrov and his closeness with Tito.[15][24]

After the funeral, Dimitrov's body was embalmed and placed on display in Sofia's Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum. After the fall of Communism in Bulgaria, his body was buried in Sofia's central cemetery in 1990. His mausoleum was demolished in 1999.

Legacy

Bulgaria

- Dimitrovgrad, Bulgaria

- Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum 1949–1999

Russia

- Dimitrovgrad, Russia

- In Novosibirsk a large street leading to a bridge over the Ob River are both named after him. The bridge was opened in 1978.

Serbia

- Dimitrovgrad, Serbia

Romania

- In Bucharest, a boulevard was named after him (Bulevardul Dimitrov), although this name was changed after 1990 to the former Romanian king Ferdinand (Bulevardul Ferdinand).

Armenia

- Dimitrov, Armenia

Hungary

- The square Fővám tér and the street Máriaremetei út in Budapest, Hungary were named after Dimitrov between 1949 and 1991. On the square a bust of him was erected in 1954, replaced by a full-length statue in 1983 and taken to the eponymous street a year later. Both sculptures are exhibited since 1992 in the Memento Park.

_fal%C3%A1n_Georgi_Dimitrov_eml%C3%A9kt%C3%A1bl%C3%A1ja._Fortepan_17159.jpg.webp) A memorial to Dimitrov in Budapest

A memorial to Dimitrov in Budapest

Slovakia

- During the times of the communist rule, an important chemical factory in Bratislava was called "Chemické závody Juraja Dimitrova" (colloquially Dimitrovka) in his honour. After the Velvet revolution, it was renamed Istrochem.

East Germany

- In then-East Berlin's Pankow district, a street that since 1874 had been named Danziger Straße — after the formerly German city Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) — was in 1950 renamed Dimitroffstraße (Dimitrov Street) by the Communist East German regime. It also lent its name to an U-Bahn station. After German unification, the Berlin Senate in 1995 restored the street's name to Danziger Straße, and the U-Bahn station was renamed Eberswalder Straße.

Benin

- A large painted statue of Dimitrov survives in the centre of Place Bulgarie in Cotonou, Republic of Benin, decades after the country abandoned Marxism–Leninism and the colossal statue of Vladimir Lenin was removed from Place Lenine.

Ukraine

- Dymytrov, now Myrnohrad in Ukraine was named Dymytrov between 1972 and 2016.

Yugoslavia

- After the 1963 Skopje earthquake, Bulgaria joined the international reconstruction effort by donating funds for the construction of a high school, which opened in 1964. In order to honor the donor country's first post-World War II president, the high school was named after Georgi Dimitrov, a name it still bears today.

- The town of Caribrod (Цариброд) in what was then the People's Republic of Serbia, FPRY was renamed in 1950 to Dimitrovgrad (Димитровград) to honor the late Bulgarian leader, despite the Tito-Stalin split. The name has been kept since, although in recent years the local city council has tried to restore the old name (most recently in 2019), and some people prefer the older name to avoid confusion with the Dimitrovgrad in Bulgaria.

Cuba

- A main avenue in the Nuevo Holguin neighborhood, which was built during the 1970s and 1980s in the city of Holguín, Cuba is named after him.

- Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias Jorge Dimitrov in Bayamo is named after him.

- IPUEC Jorge Dimitrov (Ceiba 7) school in Caimito

- Primary School Escuela Primaria Jorge Dimitrov in Havana

Nicaragua

The Sandinista government of Nicaragua renamed one of Managua's central neighbourhoods "Barrio Jorge Dimitrov" in his honor during that country's revolution in the 1980s.

Cambodia

- There is also an avenue (#114) named for him in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Italy

- There is a Georgi Dimitrov street in the city of Reggio Emilia, Emilia Romagna administrative region.

Works

References

Citations

- "Dimitrov". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Staar, Richard Felix (1982). Communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Hoover Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0817976927.

- Ценкова, Искра (21–27 March 2005). "По следите на червения вожд" (in Bulgarian). Тема. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- Banac 2003, p. xvii.

- Banac 2003, p. xix.

- Banac 2003, p. xxii.

- Carr, E.H. (1969). The Interregnum, 1923–24. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 201.

- Ceplair, Larry (1987). Under the Shadow of War: Fascism, Anti-Fascism, and Marxists, 1918–1939. Columbia University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0231065320. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- Georgi Dimitrov, And Yet It Moves: Concluding Speech before the Leipzig Trial, Sofia: Sofia Press, 1982, p. 15

- Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem. New York: The Viking Press, 1965. p. 188

- "The Man who defied Goering, Yet Lived", The Milwaukee Journal

- John D. Bell, The Bulgarian Communist Party from Blagoev to Zhivkov, Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1985, p. 47

- Tzvetan Todorov, "Stalin close up." Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 5.1 (2004): 94–111 at p. 95.

- Banac 2003, pp. 62, 89–91.

- Gallagher, T. (2001). Outcast Europe: The Balkans, 1789–1989, from the Ottomans to Milošević. Routledge. p. 181. ISBN 978-0415270892. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

- Nationalism from the Left: The Bulgarian Communist Party During the Second World War and the Early Post-War Years, Yannis Sygkelos, Brill, 2011, ISBN 9004192085, p. 156.

- H.R. Wilkinson Maps and Politics. A Review of the Ethnographic Cartography of Macedonia, Liverpool, 1951. pp. 311–312.

- Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise, Viktor Meier, Routledge, 2013, ISBN 1134665113, p. 183.

- Hugh Poulton Who are the Macedonians?, C. Hurst & Co, 2000, ISBN 1850655340. pp. 107–108.

- Hoxha, Enver (1982). The Titoites. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House. p. 417.

- H.R. Wilkinson Maps and Politics. A Review of the Ethnographic Cartography of Macedonia, Liverpool, 1951. p. 312.

- Dimitrov, Georgi. "Political Report of the Central Committee to the V Congress of the Bulgarian Workers' Party (Communists)". Revolutionary Democracy. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023.

- Chang, Jung; Halliday, Jon (2011). Mao: The Unknown Story. Knopf Doubleday. p. 254. ISBN 978-0307807137.

- Chary, F.B. (2011). The History of Bulgaria. ABC-CLIO. p. 131. ISBN 978-0313384479. Retrieved 2015-09-13.

Cited works

- Banac, Ivo (2003). The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov, 1933–1949. New Haven: Yale U.P. ISBN 0300097948.

Further reading

- Dalin and Firsov, Dimitrov and Stalin, 1934–1943: Letters from the Soviet Archives, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000

- Dimitrov and Banac, The Diary of Georgi Dimitrov, 1933–1949, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003

- Marietta Stankova, Georgi Dimitrov: A Life, London: I. B. Tauris, 2010

External links

- Georgi Dimitrov Reference Archive at Marxist Internet Archive.

- Selected Works in English (Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3) in PDF format, published in Bulgaria in 1972

- Georgi Dimitrov: 90th Birth Anniversary, containing biographical information.

- Video A Better Tomorrow: The Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum from UCTV (University of California)

- Newspaper clippings about Georgi Dimitrov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW