Marinus van der Lubbe

Marinus van der Lubbe (13 January 1909 – 10 January 1934) was a Dutch communist who was tried, convicted, and executed by the German Nazi regime for allegedly setting fire to the Reichstag building - the national parliament of Germany - on 27 February 1933. During his trial, the prosecution argued that van der Lubbe had acted on behalf of a wider communist conspiracy, while left-wing anti-Nazis argued that the fire was a false flag attack arranged by the Nazis themselves. Most historians agree that van der Lubbe acted alone. Nearly 75 years after the event, the German government granted van der Lubbe a posthumous pardon.[1]

Marinus van der Lubbe | |

|---|---|

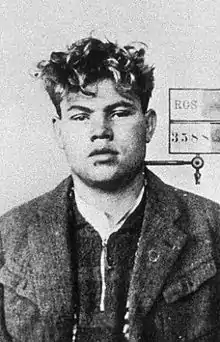

Van der Lubbe in 1933. | |

| Born | 13 January 1909 Leiden, Netherlands |

| Died | 10 January 1934 (aged 24) |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Burial place | Südfriedhof |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Occupation(s) | Political activist and trade unionist |

| Known for | Allegedly setting the Reichstag fire |

| Political party | Communist Party Holland (until 1931) |

| Movement | Council communism |

| Criminal charges | High treason and arson crime |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Criminal status | Executed (Posthumously pardoned on 6 December 2007) |

Early life

Marinus van der Lubbe was born in Leiden in the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. His parents were divorced, and after his mother died when he was twelve years old, he went to live with his half-sister's family in the town of Oegstgeest. During part of his youth van der Lubbe worked as a bricklayer. He was nicknamed Dempsey after boxer Jack Dempsey because of his great strength. While working, van der Lubbe became acquainted with the labour movement; in 1925, at age 16, he joined the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN) and its youth section, the Communist Youth Bund (CJB).

In 1926 he was injured at work, getting lime in his eyes, which hospitalised him for a few months and almost blinded him. Since the injury forced him to quit his job, he was unemployed with a pension of 7.44 guilders a week (roughly US$3.05 at the time, equivalent to US$52.41 in 2023). After some conflicts with his sister, van der Lubbe relocated to Leiden in 1927. There he learned to speak some German and founded the Lenin House, where he organised political meetings. While working for the Tielmann factory, a strike began. Van der Lubbe claimed to the management to be one of the ringleaders and offered to accept any punishment if no one else was punished, even though he was clearly too inexperienced to have been involved seriously. During the trial, he tried to claim sole responsibility and was purportedly hostile to the idea of not being punished.

Afterwards, van der Lubbe planned to emigrate to the USSR, but he lacked the funds to do so. He was active politically among unemployed workers until 1931, when he had a disagreement with the CPN and instead approached the Group of International Communists. In 1933, van der Lubbe fled to Germany to work for communism there. He had a criminal record for several attempted arsons.[2]

Reichstag fire

On 27 February 1933, van der Lubbe was arrested in the Reichstag building, soon after the building had begun burning. Van der Lubbe confessed and claimed to have acted alone and have set the Reichstag building afire in an attempt to rally German workers against fascist rule.[3]

He was tried along with the chief of the Communist Party of Germany and three members of the Bulgarian Communist Party, who were working in Germany for the Communist International. At his trial, van der Lubbe was convicted and sentenced to death for the Reichstag fire. The four other defendants (Ernst Torgler, Georgi Dimitrov, Blagoy Popov, and Vasil Tanev) were acquitted. Van der Lubbe was guillotined in a Leipzig prison yard on 10 January 1934, three days before his 25th birthday. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the Südfriedhof (South Cemetery) in Leipzig.

After World War II, attempts were made by his brother, Jan van der Lubbe, to have the original verdict reversed. In 1967, his sentence was changed by a judge from death to eight years in prison. In 1980, after more lengthy complaints, a West German court reversed the verdict entirely, but that was criticised by the state prosecutor. The case was re-examined by the Federal Court of Justice of Germany for three years. In 1983, the court made a final decision on the matter and reversed the result of the 1980 trial on grounds that there was no basis for it and so it was illegal. However, on 6 December 2007 the public prosecutor general Monika Harms nullified the entire verdict and posthumously pardoned van der Lubbe, based on a 1998 German law that makes it possible to overturn certain cases of Nazi injustice. The court's determination was based on the premise that the National Socialist regime was, by definition, unjust, and since the case's death sentence had been motivated politically, it was likely to have contained an extension of that injustice. The conclusion was independent of the factual question of whether or not van der Lubbe had actually set the fire.[4][5][6]

Claimed responsibility

Historians disagree as to whether van der Lubbe acted alone, as he said, to protest the condition of the German working class, or was involved in a larger conspiracy. The Nazis blamed a communist conspiracy. Responsibility for the Reichstag fire remains an ongoing topic of debate and research in modern historical scholarship.[7][8][9] Journalist William Shirer, writing in 1960, surmised that van der Lubbe was goaded into setting a fire at the Reichstag but that the Nazis had set their own more elaborate fire at the same time.[10] According to Ian Kershaw, writing in 1998, the consensus of nearly all contemporary historians is that van der Lubbe had in fact set the Reichstag afire.[11]

Lex van der Lubbe

"Lex van der Lubbe" is the colloquial term for the Nazi law concerning the imposition and execution of the death penalty, passed on 29 March 1933. The name comes from the fact that the law formed the legal basis for the imposition of the death penalty against van der Lubbe.

The Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February 1933 included a list of crimes for which the death penalty was to be imposed instead of a life sentence, as was previously the case. The law concerning the imposition and execution of the death penalty was passed by Hitler's government on 29 March (on the basis of the Enabling Act which had been passed on 23 March 1933). It extended the law retroactively to 31 January 1933, thereby violating Article 116 of the Weimar Constitution, which prohibited retroactive penalties. The Enabling Act itself, however, made this legislation constitutional, provided the office of the president and the Reichstag and Reichsrat were not affected.[12] It could thus be applied to van der Lubbe, who had admitted in court that he had set fire to the Reichstag on 27 February.

The law was ultimately repealed by the Allied Control Council on 30 January 1946 through Control Council Act No. 11.

Exhumation

In January 2023, bodily remains at van der Lubbe's supposed grave were exhumed. This was done to ascertain the precise location and identity of the grave, as well as to allow for a toxicological analysis. Van der Lubbe had appeared sleepy and apathetic during his trial, resulting in suspicions that he had been drugged.[3][13] These remains were determined to be van der Lubbe's after several months of forensic investigations. The toxicology report showed no evidence that van der Lubbe had been administered drugs, although it was noted that due to decomposition it is impossible to scientifically prove one way or the other and that the question remains open. [14]

References

- "75 years on, executed Reichstag arsonist finally wins pardon". the Guardian. 12 January 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Evans, Richard J. (2004). The Coming of the Third Reich. United States of America: Penguin Publishing. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-14-303469-8.

- Oltermann, Philip (2023-02-26). "'Blind chance' or plot? Exhumation may help solve puzzle of 1933 Reichstag blaze". The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- Announcement of the Attorney General of Germany (in German)

- "Marinus van der Lubbe gerehabiliteerd" [Marinus van der Lubbe rehabilitated] (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- Connolly, Kate (12 January 2008). "75 years on, executed Reichstag arsonist finally wins pardon". The Guardian.

- "The Reichstag Fire". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- DW Staff (27 February 2008). "75 Years Ago, Reichstag Fire Sped Hitler's Power Grab". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- Rabinbach, Anson (Spring 2008). "Staging Antifascism: The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror". New German Critique. 35 (1): 97–126. doi:10.1215/0094033X-2007-021.

- Shirer, William (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Simon & Schuster.

- Kershaw, Ian (1998). Hitler Hubris. Penguin Books. pp. 456–458, 731–732.

- Wesel, Uwe (2006). Geschichte des Rechts. Von den Frühformen bis zur Gegenwart [History of law. From the early forms to the present] (in German) (3rd revised and expanded ed.). Beck, Munish. p. 496. ISBN 3-406-47543-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Herrmann, Boris (2023-03-09). "Der Rest ist Geschichte". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- "Body of arsonist Marinus van der Lubbe identified – no drug residue". www.spiegel.de. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

Other sources

- Biography Marinus van der Lubbe on libcom.org history.

- Martin Schouten: Rinus van der Lubbe 1909–1934 – een biografie. De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam 1986.(in Dutch)

- Alexander Bahar and Wilfried Kugel: Der Reichstagbrand, edition q (2001) German language only.

- Hersch Fischler: Zum Zeitablauf der Reichstagsbrandstiftung. Korrekturen der Untersuchung Alfred Berndts, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 55 (2005), S. 617–632. (with English summary)

External links

Media related to Marinus van der Lubbe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marinus van der Lubbe at Wikimedia Commons- English translation of The Reichstag Fire (1963) by Fritz Tobias, with introduction by A. J. P. Taylor

- Dutch Council Communism and Van der Lubbe Burning the Reichstag – The question of "exemplary acts" – the political repercussions of his act on his comrades.

- Zuidenwind Filmproductions at www.zuidenwind.nl Documentary about Marinus van der Lubbe

- Marinus van der Lubbe rehabilitated (English)