István Friedrich

István Friedrich (anglicised as Stephen Frederick; 1 July 1883 – 25 November 1951) was a Hungarian politician, footballer and factory owner who served as prime minister of Hungary for three months between August and November in 1919. His tenure coincided with a period of political instability in Hungary immediately after World War I, during which several successive governments ruled the country.

István Friedrich | |

|---|---|

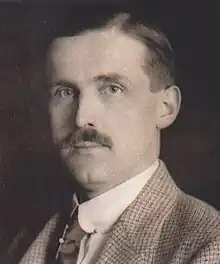

Friedrich in August 1919 | |

| 24th Prime Minister of Hungary | |

| In office 7 August 1919 – 24 November 1919 | |

| Monarchs | Archduke Joseph August as Regent himself as acting Head of State |

| Preceded by | Gyula Peidl |

| Succeeded by | Károly Huszár |

| Acting Head of State of Hungary | |

| In office 23 August 1919 – 24 November 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Archduke Joseph August |

| Succeeded by | Károly Huszár |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 July 1883 Malacka, Austria-Hungary (now Malacky, Slovakia) |

| Died | 25 November 1951 (aged 68) Vác, Hungarian People's Republic |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Political party | F48P (1912–1919) KNP (1919) KNEP (1919–1920) KNP (1920–1922) KNFPP (1922–1926) KGSZP (1926–1935) KE (1935–?) |

| Spouse | Margit Asbóth |

| Children | Gita Erzsébet |

| Profession | Politician, footballer, factory owner |

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of birth | 1 July 1883 | ||

| Place of birth | Malacka, Austria-Hungary | ||

| Date of death | 25 November 1951 (aged 68) | ||

| Place of death | Vác, Hungary | ||

| Position(s) | Right winger | ||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) |

| ? | Műegyetemi AFC | ? | (?) |

| International career | |||

| 1904 | Hungary | 1 | (0) |

| *Club domestic league appearances and goals | |||

Biography

Early life

Friedrich was born into a family of German origin[1] as the son pharmacist János Friedrich and Erzsébet Wagner on 1 July 1883 in the town of Malacka (now Malacky, Slovakia). He finished his secondary studies at the High Gymnasium of Pozsony (now Bratislava, Slovakia). As a right winger footballer of the Műegyetemi AFC, he played once for the Hungary national football team on 9 October 1904, when they suffered a 4–5 defeat against Austria in WAC-Platz. Thus, Friedrich became the first prime minister in the world history who had earlier played for a national football team on a professional level. Following the game, he functioned as a referee, belonging to the second generation.[2]

Friedrich studied engineering at the universities of Budapest (where he graduated in 1905) and Charlottenburg before studying law at Budapest and Berlin.[3] He worked as an engineer for AEG in Berlin until 1908.[1][3] That year he returned to Hungary and married Margit Asbóth, daughter of Emil Asbóth, the owner of the Ganz-Danubius Company, one of the largest industrial conglomerates in Hungary, although he did not work for his father-in-law, instead setting up his own business in Mátyásföld, on the outskirts of the Hungarian capital.[1] On his return to Hungary he was engaged in the manufacture of machinery and owned an iron foundry; he sold the factory in 1920.[4][1][3]

Friedrich spent eight years working as an emigrant in the United States.[4] In 1912 he joined the Independence Party of Mihály Károlyi and was considered as part of the left wing of the liberals.[1] During that time he also came in contact with a Masonic lodge.[3] Soon, Friedrich became president of his party's Mátyásföld branch.[1] In 1914 he had accompanied Mihály Károlyi to the United States[4] and since then was one of his closest friends. Károlyi recalled him as a "youtful, idealistic and enthusiastic" who held in high esteem for his "resolute desire for peace".[1] On his way home, Friedrich was interned in France for a short time following the outbreak of the World War I. Returning to Hungary after a successful escape through Spain and Italy, he volunteered and served in the Austro-Hungarian Army, in the artillery, with the rank of lieutenant, and fought at the Uzsok Pass in Carpathian Ruthenia.[3] After having been declared unfit for service on the front, he went to work as a rearguard in Pilsen (Škoda Works) and Vienna (Arsenal), then served as commander of a technical repair unit until his demobilisation from the army in 1917.[3]

Cabinet of Mihály Károlyi and the Soviet republic

During the Aster Revolution at the end of World War I, he led large protests at the Royal Palace of Budapest to demand the appointment of the Károlyi government; he actively participated in and was wounded in the so-called "Battle of the Chain Bridge" on 28 October 1918.[5][4][3] Following the formation of the government on 31 October, he was appointed Secretary of State for War in Károlyi's first cabinet on 1 November,[4][3] which came under his control because of the small size of his superior, minister Béla Linder's entity.[6] According to Károlyi, Friedrich was an "uncontrollable demagogue."[7][4] The old enthusiasm between the prime minister and his deputy minister cooled quickly. Friedrich approached the more conservative section of the party,[4] while Károlyi relied increasingly on the Social Democrats.[6]

Károlyi proclaimed himself a follower of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, thus he and his followers trusted the Entente Powers and pinned their hopes for maintaining Hungary's territorial integrity, the securing of a separate peace, and exploiting Károlyi's close connections in France. By contrast, Friedrich, as a prominent member of the moderate wing, rejected Károlyi's "naive" foreign policy and sought to set up a powerful army under the old leadership of military officers, contradicting Linder's pacifist manifesto. After the dismissal of Linder, Friedrich was a close associate of Albert Bartha, the new defence minister. He maintained a relationship with counter-revolutionary groups, thus gradually drifted into the political right-wing.[8]

In the dismemberment of the party that finally took place in January 1919 between conservatives and progressives, Friedrich left,[3] along with the majority, while Károlyi only managed to keep less than a quarter of the party next to him. Friedrich was dismissed as Secretary of State for War on 8 February 1919.[9] He formed an opposition party along with other former cabinet members, such as Minister of Education Márton Lovászy and Minister of the Interior Tivadar Batthyány.[9] In the coming decades, several former colleagues, including Lajos Varjassy, Oszkár Jászi and Mihály Károlyi himself regarded Friedrich as a traitor, who had joined the reactionary forces, abandoning the cause of the short-lived liberal democracy in Hungary.[10]

Following the resignation of the coalition government of Dénes Berinkey on 20 March 1919, which was caused by the intention of the Entente to further reduce the territory controlled by Hungary, the Social Democrats called the Communists to a coalition government, which gained power the next day, leading to the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic.[9] Most prominent liberals left the country or took refuge in the countryside.[11] However, Lovászy and Friedrich remained in the capital.[12] In the face of the Hungarian-Romanian War, the new Soviet government took numerous hostages.[12] On 19 April the authorities arrested Friedrich and sentenced him to death for counter-revolutionary activities.[12][13] With the aid of People's Commissar Zsigmond Kunfi, a former member of the Károlyi Cabinet, he managed to have the sentence commuted and soon managed to escape with the aid of some of the workers of his factory; he remained in hiding until the end of the Béla Kun government on 1 August 1919.[12]

Coup d'état of 1919

During the period of his internal exile, Friedrich became associated with the White House Comrades Association (Hungarian: Fehérház Bajtársi Egyesület), a right-wing, counter-revolutionary group, which originated from a secret society of intellectuals founded by dentist and well-known anti-Semitic political figure András Csilléry in 1916. Initially sceptical, Friedrich refused to join them and worked closely with Lovászy and Bartha to bring together the formation of a new government after the expected collapse of the Kun regime.[14]

After attempting to negotiate with the new moderate Social Democrat prime minister, Gyula Peidl, in an attempt to replace his government with a coalition where the Socialists would be forced to the background and removed, Friedrich tried to gain support for his project from the representative of the Entente.[15] Failing in both endeavours and fully aware of the conspiracies of the reactionaries, he decided to join the White House[4] to control the plot.[16] The first meeting of the conspirators took place on 1 August 1919 and it was decided that they would take power on 5 August, before the possibility that the prime minister could reach an agreement with the Entente which would reinforce his power or that he would agree to form a new coalition cabinet with the middle class parties.[17][18] The conspirators communicated their plan to Guido Romanelli, the representative of the Entente in the capital, who rejected it, and the commander of the Romanian occupation troops, who approved it[13] with the condition that the operation did not cause chaos and that the coup leaders acted promptly.[17]

The conspirators who ended up supporting Friedrich were not politicians, but bourgeoisie[19][17] (officials, university professors, dentists, etc.) with radical right leanings (anti-Semitic, anti-democratic and anti-monarchical).[16] Their first candidate for prime minister was Gyula Pekár, a novelist of little success who was very close to the late prime minister István Tisza.[14] A few days later, Friedrich recommended his friend Márton Lovászy to hold the position of prime minister, however the leadership of the White House objected it on ideological grounds.[16] On 4 August 1919, Friedrich led the monarchical delegation that persuaded Archduke Joseph of Austria, who had "universal prestige" in Hungary, according to Gusztáv Gratz, to travel to Budapest that night to carry out a coup that would overthrow the government of Gyula Peidl, controlled by the trade unionists.[4] However, Joseph was unpopular with the membership of the White House because of his supportive role in the Aster Revolution.[20]

On 5 August, Vilmos Böhm, envoy to Vienna, phoned Budapest to inform his government of his meeting with representatives of the Entente Powers, where they accepted a moderate reorganisation of the Peidl cabinet instead of establishment of a grand coalition. A White House spy informed Csilléry of the conversation's content.[20] Böhm's telephone call confirmed the counterrevolutionary forces' worst fears; the Allied representatives were willing to recognise Peidl's cabinet. The leaders of the White House then felt that they needed to take power immediately.[21]

With the control of the police and some of the military units in the capital on 6 August 1919, that afternoon members of the White House, most notably General Ferenc Schnetzer and Jakab Bleyer, arrested Károly Peyer, the Minister of the Interior, learning that the rest of the cabinet was meeting in council at the Sándor Palace, where they were detained by the coup plotters.[22] At the same time, they had occupied the Ministry of Defence without resistance.[22] After some protests, Peidl's cabinet agreed to resign[13] under threats and with the coup plotters' promise that a coalition government would be formed.[23] Friedrich's participation in the coup was minimal, as he has always tried to resolve the situation by negotiation. Historian Eva S. Balogh argued that he wanted to re-establish the early phases of the Károlyi regime, yet exclude the later shift that led to the Social Democratic Party having more influence in the affairs of the state.[24]

Prime Minister of Hungary

Following the success of the coup, which counted on the Romanian neutrality and the tacit support of the British and the Italians,[19] on 7 August 1919 Friedrich was named prime minister while the archduke became regent.[7][19][25][21][13] After a one-week transitional period lasting until 15 August, his cabinet was composed primarily of former members of the government of Prime Minister Mihály Károlyi, belonging mainly to the more conservative wing of his Independence Party, which had split during his rule. Friedrich founded his own party Christian National Party (KNP) but it did not have mass support.[26] He was far to the left of the counter-revolutionaries who had plotted the coup against the Peidl government and attempted to carry out, ultimately unsuccessfully, the moderate program that had originally been proposed at the beginning of the government of Károlyi.[27] His government was even weaker than Peidl's and was little more than a collection of conspirators[19] and unknown figures, without members of the nobility that could serve to attract the counterrevolutionary right.[28] The cabinet could not count on British nor Italian military aid, given the practical absence of troops from these countries in the capital, nor could it count on Romanian aid, whose units occupied the city and the eastern territories.[19] The government of Bucharest refused to recognise the Friedrich cabinet.[19] The government of Szeged and the French, for their part, almost immediately tried to do away with the Friedrich government or, if this was impossible, to alter its composition.[19] The neighbouring states, fearful of a restoration of the Habsburgs, supported the French position and showed their opposition to the appointment of Archduke Joseph.[29]

After the seizure of power, Friedrich tried to limit reckoning with the former government's criminals, without much success.[30] Attacks were soon launched on Jews, accused by many reactionaries of being responsible for the Soviet government and any crimes committed during its period.[30] In spite of this, in mid-August he had succeeded in forming a broad coalition government[31] which, however, was not joined by the Socialists.[32] Without these, the Entente refused to recognise the government.[33][29] The Entente feared that the government, with a ruler from the ancient imperial family, would restore the dynasty.[13]

On 7 August, Friedrich abolished institutions of the Hungarian Soviet Republic and instituted private ownership in industry, commerce and agriculture, following decrees which abrogated the Soviet legacy from the former Peidl Government.[4][13]

On 23 August, the Archduke decided to resign the regency before opposition from the powers;[34] Friedrich thus lost one of the pillars of his government and the post of head of state remained unfilled.[29]

His attempts to create a military force loyal to his government, independent of the National Army and theoretically subordinate to the government of Szeged, failed due to the Romanian opposition.[28] The few units that managed to reunite mostly defected to the side of Miklós Horthy when they entered Szeged, after evacuating it of the Romanian formations.[35]

Militarily limited, Friedrich tried to politically underpin his government during August and September with successive modifications of the cabinet, first to the left and then to the right, without thereby achieving the recognition of the Entente.[35][36] With each change of government, refugees, and especially Viennese counterrevolutionaries, were gaining power.[37] Despite failing to achieve recognition of the major powers, the alliances resulted in the formation of a powerful new political party, the Christian National Union Party (KNEP).[37] This party, created in October, brought together important politicians from the northwestern territories of Hungary, the Catholic Church and certain refugees from Transylvania, such as those grouped around István Bethlen and Pál Teleki.[38] Part of the upper-class bourgeoisie also supported the new organisation.[39] The government of Szeged, which had recognised Friedrich's government, had disappeared;[39] the main weakness of this government was the military, and the uncertain possibility at the outset that Horthy should not subordinate his National Army to Friedrich's government, as it happened.[40]

Friedrich tried to earn his loyalty by officially naming himself Commander-in-Chief of the Hungarian Army, a position he already held, but he did not manage to subordinate Horthy to his government, nor transfer his government to the capital.[40] Meanwhile, Horthy controlled the Western territories free of the Romanian occupation through the officers of his army, leaving aside the official officers loyal to the government of Friedrich.[40]

At the beginning of November, the Romanians showed themselves willing to evacuate the capital and the whole territory to the west of the Tisza River, which happened to be controlled by the forces of Horthy, given the lack of significant forces directly subordinate to the government.[41] Faced with the possibility of an extension of a White Terror, practised by officers loyal to Horthy's units,[31] both the Allies and representatives close to the government tried to convince Horthy to limit the crackdown in the capital.[41] After initially promising to subject the Army to control of a new coalition government, he contradicted them and maintained control over it.[42] The large number of detainees under his command intensified after the arrival of Horthy to the capital; political prisoners soon filled the jails.[43]

On 17 November, the Friedrich cabinet imposed Prime Ministerial Decree ME 5985/1919 which established universal suffrage by secret ballot to all citizens (including women) over the age of 24. Thus 74% of the adult population (and 40% of the total population) had access to vote in the January 1920 parliamentary election which was the most democratic election in Hungarian history until the 1945 parliamentary election, as three million citizens had the right to vote.[44] However the first universal suffrage in Hungary proved to be short-lived and temporary, as in early 1922, the Bethlen cabinet at the beginning of the era of consolidation, imposed residency, citizenship, education, age and gender restrictions and reintroduced use of the open ballot system in countryside via Prime Ministerial Decree ME 2200/1922, reducing suffrage by 12% points to 28% of the total population.[45]

Friedrich remained in office as Prime Minister until 24 November,[36] and then transferred to the Ministry of Defence[42] until 15 March 1920, a position of little significance given that the troops obeyed only Horthy.[36][13] The pressure of the socialist left and the reactionaries led by Miklós Horthy, both supported by the representative of the Entente, led to the resignation of Friedrich.[33] The new government, of which he was a part, was a coalition cabinet that included socialists, liberals and agrarians, but which was controlled by the KNEP.[42] It was led by Károly Huszár, of little political stature and with few followers, elected as a result of the rejection of the candidacy of Horthy and his supporters to that of Albert Apponyi.[42] Supporters of Friedrich theoretically occupied key ministries, such as defence, foreign and interior, but the maintenance of control of the army by Horthy and its independence from the government foiled the chances of Friedrich maintaining political power in the country.[42]

Exit from power

In the elections of February 1920, Friedrich was elected by the KNEP but almost immediately formed an own group with his followers, one of several groups that arose from the parties which had contended in the elections.[46] He was deputy of a small group of Christian Democrats from 1920 to 1939.[13] In 1921, accused in the trial for the murder of István Tisza, he managed to be acquitted.[13] In November of the same year, he was again arrested for participating in the failed attempt to restore the Emperor Charles.[13] Shortly afterwards he became marginalised from national politics.[13]

In July 1951, he was arrested by the government of the Hungarian People's Republic under Mátyás Rákosi and falsely accused of plotting his overthrow.[13] He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison, but died on 25 November 1951.[47] He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1990.[13]

References

- Balogh 1976, p. 272.

- Tóth-Szenesi, Attila (17 April 2017). "A fociválogatottban játszott, később miniszterelnök lett". Index.hu. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Roszkowski & Kofman 2016, p. 266.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 55.

- Balogh 1976, pp. 272–273.

- Balogh 1976, p. 273.

- Szilassy 1969.

- Markó 2006, p. 156.

- Balogh 1976, p. 274.

- Balogh 1976, p. 270.

- Balogh 1976, pp. 274–275.

- Balogh 1976, p. 275.

- Roszkowski & Kofman 2016, p. 267.

- Balogh 1976, p. 276.

- Balogh 1976, pp. 276–278.

- Balogh 1976, p. 278.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 56.

- Balogh 1976, pp. 279–280.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 135.

- Balogh 1976, p. 279.

- Balogh 1976, p. 280.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 61.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 62.

- Balogh 1976, p. 281.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 64.

- Balogh 1976, pp. 281, 283.

- Balogh 1976, pp. 281–282.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 137.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 136.

- Balogh 1976, p. 284.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 68.

- Balogh 1976, p. 285.

- Balogh 1976, p. 286.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 67.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 138.

- Szilassy 1971, p. 69.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 139.

- Mócsy 1983, pp. 139–140.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 140.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 141.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 151.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 155.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 156.

- Romsics 2001, p. 75.

- Romsics 2001, p. 88.

- Mócsy 1983, p. 168.

- Roszkowski & Kofman 2016, pp. 266–267.

Bibliography

- Balogh, Eva S. (1976). "Istvan Friedrich and the Hungarian coup d'etat of 1919: A Reevaluation". Slavic Review. 35 (2): 269–286.

- Markó, László (2006). A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig: Életrajzi Lexikon [Great Officers of State in Hungary from King Saint Stephen to Our Days: A Biographical Encyclopedia] (in Hungarian). Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963-208-970-7.

- Mócsy, István I. (1983). The Uprooted: Hungarian Refugees and Their Impact on Hungary's Domestic Politics, 1918-1921. EAST EUROPEAN MONOGRAPHS. Brooklyn College Press. ISBN 0-88033-039-2.

- Romsics, Ignác (2001). "Választójog és parlamentarizmus a 20. századi magyar történelemben". In Romsics, Ignác (ed.). Múltról a mának. Osiris. ISBN 963-389-596-0.

- Roszkowski, Wojciech; Kofman, Jan (2016). Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 1208. ISBN 9781317475941.

- Szilassy, Sándor (1969). "Hungary at the Brink of the Cliff 1918-1919". East European Quarterly. 3 (1): 95–109.

- Szilassy, Sándor (1971). Revolutionary Hungary 1918–1921. Aston Park, Florida: Danubian Press. ISBN 978-08-79-34005-6.

- Vida, István (2011). Magyarországi politikai pártok lexikona (1846–2010) [Encyclopedia of the Political Parties in Hungary (1846–2010)] (in Hungarian). Gondolat Kiadó. p. 187. ISBN 978-963-693-276-3.