Italian irredentism in Savoy

Italian irredentism in Savoy was the political movement among Savoyards promoting annexation to the Savoy dynasty's Kingdom of Italy. It was active from 1860 to World War II.

History

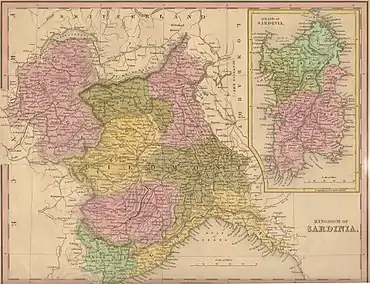

Italian irredentists were citizens of Savoy who considered themselves to have ties with the House of Savoy dynasty. Savoy was the original territory of the duke of Savoy that later became King of Italy. Since the Renaissance the area had ruled over Piedmont and had for regional capital the town of Chambéry. The official language of Savoy was French since the 15th century,[1] and was divided administratively in Savoie Propre (Chambéry), Chablais (Thonon), Faucigny (Bonneville), Genevois (Annecy), Maurienne (Saint Jean de Maurienne) and Tarentaise (Moûtiers). Vaugelas, a native of the duchy became one of the most renowned French linguists.

In spring 1860 the area was annexed to France after a referendum and the administrative boundaries changed, but a segment of the Savoyard population demonstrated against the annexation. Indeed, the final vote count on the referendum announced by the Court of Appeals was 130,839 in favour of annexation to France, 235 opposed and 71 void, showing a questionable complete support for French nationalism (that motivated criticisms about rigged results).[2]

Presently, the situation seems the following: generally, it does not exist any will to separate Savoy and Piedmont. In the highest part of the country, Maurienne, Tarentaise and Upper-Savoy (Albertville and Beaufortain), the population is resolutely for the statu quo. In Genevois, Faucigny and Chablais, if ever should produce a change, the annexation by Switzerland is preferred to any other solution.[3]

At the beginning of 1860, more than 3000 people demonstrated in Chambéry against the annexation to France rumours. On 16 March 1860, the provinces of Northern Savoy (Chablais, Faucigny and Genevois) sent to Victor Emmanuel II, to Napoleon III, and to the Swiss Federal Council a declaration - sent under the presentation of a manifesto together with petitions - where they were saying that they did not wish to become French and shown their preference to remain united to the Kingdom of Sardinia (or be annexed to Switzerland were a separation from Sardinia unavoidable).[4]

Giuseppe Garibaldi complained about the referendum that allowed France to annex Savoy and Nice, and a group of his followers (between the Italian Savoyards) took refuge in Italy in the following years. With a 99.8% vote in favour of joining France, there were allegations of vote-rigging.[5]

Some opposition to French rule was manifest when, in 1919, France officially (but contrary to the annexation treaty) ended the military neutrality of the parts of the country of Savoy that had originally been agreed to at the Congress of Vienna, and also eliminated the free trade zone - both treaty articles having been broken unofficially in World War I. France was condemned in 1932 by the international court for noncompliance with the measures of the treaty of Turin, regarding the countries of Savoy and Nice. Indeed, in 1871 a strong break away movement appeared in north and central Savoy against the annexation. The Republican Committee of the town of Bonneville considered that "the 1860 vote, was the result of imperial pressure, and not the free demonstration of the will of our country" and called for a new Referendum: France sent 10,000 troops to Savoy to restore order.

In 1861, the Associazione Oriundi Savoiardi e Nizzardi Italiani was founded in Italy,[6] an association of the Italian Savoyards that lasted one century until 1966.

During the fascist period in the early 1940s, organizations were created that promoted the unification of Savoy to the Kingdom of Italy. The fascist members were nearly one hundred in 1942, concentrated mainly in Grenoble and Chambéry.[7]

When Italy occupied Savoy in November 1942 these fascist groups claimed that nearly 10,000 Savoyards demanded the unification to Italy, but nothing was done mainly because the King of Italy opposed it.[8]

After World War II all the organizations of the Irredentist Savoyards were outlawed by the French authorities of Charles de Gaulle.

Most of the remaining Irredentist Savoyards supported in the 1950s and 1960s the development of autonomistic political organizations of Savoy, like the Mouvement Région Savoie (Savoy Regional Movement).

Italian-occupied Savoy

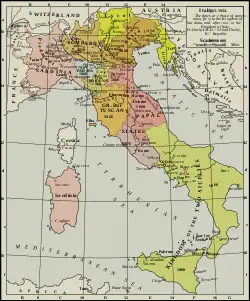

Only in 1940 did the Italian Savoyards fulfil their irredentism, when some small areas bordering the Alps were annexed by Italy. The initial zone was 832 km² and contained 28,500 inhabitants.[9]

In November 1942, in conjunction with "Case Anton", the German occupation of most of Vichy France, the Royal Italian Army (Regio Esercito) expanded its occupation zone. Italian forces took control of Grenoble, Nice, the Rhône River delta, and nearly all of Savoy.

A process of Italianization of the schools in Savoy was started, but was never fully implemented. Only a few Italian Savoyards were voluntarily enrolled in the Italian Army through fascist organizations like the Camicie Nere, most of them rejoined the resistance and fought against the invaders.

Most of the Irredentist Savoyards actively helped the Jews in the occupied zone in Savoy, a region that acted as a refugee zone for Jews fleeing persecution in Vichy France during World War II.[10]

The projects to incorporate Savoy to the Kingdom of Italy were supported by the fascist Savoyards of Grenoble,[11] but nothing was done even because in September 1943 Nazi Germany substituted Italy in the occupation of Savoy.

The Savoyard dialect

Savoyards historically have spoken a dialect related to the Arpitan language: the Savoyard dialect. Arpitan is spoken in France, in Switzerland and in Italy. However, French is the predominant language today.

During the fascist occupation in 1942-1943, Italian authorities promoted a process of Italianization of all the people of Savoy, mainly related to the use of Italian in substitution of the Savoyard dialect.[12]

See also

References

- Honoré Coquet, Les Alpes, enjeu des puissances européennes : L'union européenne à l'école des Alpes ?, L'Harmattan, 2003, 372 p. (ISBN 978-2-29633-505-9), p. 190.

- Wambaugh, Sarah & Scott, James Brown (1920), A Monograph on Plebiscites, with a Collection of Official Documents, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 599

- F. ENGELS, Savoyen, Nizza und die Rhein, Berlin, 1860

- Section: our country, Savoy / History

- The Times (April 28 1860): Universal suffrage in Savoy

- Text (in Italian) of "Bollettino" from the Savoiardi association

- Fascism's European Empire -By Davide Rodogno

- Vignoli, Giulio. Gli Italiani Dimenticati p. 130

- Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt. Germany and the Second World War - Volume 2: Germany's Initial Conquests in Europe, pg. 311

- Robert O. Paxton. Vichy France, Old Guard, New Order. 1972

- Giulio Vignoli, Gli italiani dimenticati, Roma, Giuffè, 2000, p. 130. (in Italian)

- Jean-Louis Panicacci, « Occupation italienne », nicerendezvous.com.

Bibliography

- Bosworth, R. J. B. Mussolini's Italy: Life Under the Fascist Dictatorship, 1915-1945. Penguin Books. London, 2005.

- De Pingon, Jean. Savoie Francaise. Histoire d'un pays annexé. Editions Cabédita. Lyon, 1996.

- Rodogno, Davide. Fascism European Empire. Cambrigge University Press. Cambridge, 2004.

- Vignoli, Giulio. Gli Italiani Dimenticati. Ed. Giuffè. Roma, 2000