Roman Catholic Diocese of Viviers

The Diocese of Viviers (Latin: Dioecesis Vivariensis; French: Diocèse de Viviers [djɔsɛz də vivje]) is a Latin Church diocese of the Catholic Church in France. Erected in the 4th century, the diocese was restored in the Concordat of 1822, and comprises the department of Ardèche, in the Region of Rhône-Alpes. Currently the diocese is a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Lyon. Its current bishop is Jean-Louis Marie Balsa, appointed in 2015.

Diocese of Viviers Dioecesis Vivariensis Diocèse de Viviers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Ecclesiastical province | Lyon |

| Metropolitan | Archdiocese of Lyon |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 5,556 km2 (2,145 sq mi) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2014) 327,072 285,000 (est.) (87.1%) |

| Parishes | 24 'new parishes' |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | 4th Century |

| Cathedral | Cathedral of St. Vincent in Viviers, Ardèche |

| Patron saint | Saint Vincent |

| Secular priests | 98 (diocesan) 44 (Religious Orders) |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Vacant |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Olivier de Germay |

| Bishops emeritus | François Blondel |

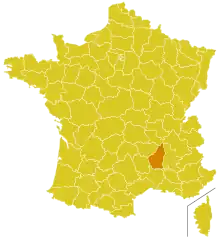

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| Website of the Diocese | |

History

Saint Andéol, disciple of Saint Polycarp, evangelized the Vivarais under Emperor Septimius Severus and was martyred in 208.

The "Old Charter", drawn up in 950 by Bishop Thomas,[1] the most complete document concerning the primitive Church of Viviers, mentions five bishops who lived at Alba Augusta (modern Alba-la-Romaine): Januarius, Saint Septimus, Saint Maspicianus, Saint Melanius and Saint Avolus. The last was a victim of the invasion of the barbarian Chrocus (the exact date of which is unknown).

In consequence of the ravages suffered by Alba Augusta, the new bishop, Saint Auxonius, transferred the see to Viviers about 430. Promotus was probably the first Bishop of Viviers; the document also mentions later several canonized bishops: Saints Lucian and Valerius (fifth and sixth centuries); Saint Venantius, disciple of Saint Avitus, who was present at the councils held in 517 and 535; Saint Melanius II (sixth century); saints Eucherius, Firminus, Aulus, Eumachius, and Longinus (seventh century); St. Arcontius, martyr (date unknown, perhaps later than the ninth century.

It seems that the Diocese of Viviers was disputed for a long time by the metropolitan Sees of Vienne and Arles. From the eleventh century its dependence on Vienne was not contested. John II, cardinal and Bishop of Viviers (1073–1095), had the abbatial church of Cruas consecrated by Urban II and accompanied him to the Council of Clermont.

Afterwards, it is said that Conrad III gave Lower Vivaraisas to Bishop William (1147) as an independent suzerainty. In the thirteenth century, under the reign of St. Louis of France, the Bishop of Viviers was obliged to recognize the jurisdiction of the Seneschal of Beucaire. By the treaty of 10 July 1305 Philip IV of France obliged the bishops of Viviers to admit the suzerainty of the kings of France over all their temporal domain.

Viviers was often troubled by religious conflicts: the Albigensian Crusade in the thirteenth century; the revolt of the Calvinists against Louis XIII (1627–1629), which ended in the capture of Privas by the royal army; the Dragonnades under Louis XIV after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes; the war of the Camisards.

It was suppressed by the Concordat of 1802, and united to the See of Mende. Re-established in 1822, the diocese then included almost all the ancient Diocese of Viviers and some part of the ancient Diocese of Valence, Vienne, Le Puy and Uzès (see Nîmes) and was suffragan of the Archdiocese of Avignon.

Bishops

To 1000

- Januarius

- Septimius

- Maspicianus

- Melanius I

- c. 407–c. 411: Avolus

- c. 411–c. 431: Auxonius

- c. 452–c. 463: Eulalius

- c. 486–c. 500: Lucianus

- c. 507: Valerius

- c. 517–c. 537: Venantius[2]

- Rusticus[3]

- (attested 549) Melanius II[4]

- Eucherius[5]

- Firminus[6]

- Aulus[7]

- Eumachius[8]

- c. 673: Longinus.[9]

- Joannes I.[10]

- Ardulfus[11]

- c. 740: Arcontius[12]

- Eribaldus[13]

- c. 815: Thomas I.[14]

- c. 833: Teugrinus[15]

- c. 850: Celse

- c. 851: Bernoin

- c. 875: Etherius (Ætherius)[16]

- c. 892: Rostaing I[17]

- c. 908: Richard[18]

- c. 950: Thomas II[19]

- c. 965–c. 970: Rostaing II[20]

- c. 974: Arman I[21]

- c. 993: Pierre[22]

From 1000 to 1300

- 1014–1041: Arman II.[23]

- 1042–1070: Gérard[24]

- 1073–1095: Giovanni di Toscanella.[25]

- 1096–1119: Leodegarius[26]

- 1119–1124: Hatto (Atton)[27]

- 1125–1131: Pierre I

- 1133–1146: Josserand de Montaigu

- 1147–1155: Guillaume I

- 1157–1170: Raymond d'Uzès

- 1171–1173: Robert de La Tour du Pin

- 1174–1205: Nicolas[28]

- 1205–1220: Bruno (Burnon)[29]

- 1220–1222: Guillaume II.

- 1222–1242: Bermond d'Anduze

- 1244–1254: Arnaud de Vogüé

- 1255–1263: Aimon de Genève

- 1263–1291: Hugues de La Tour du Pin

- 1292–1296: Guillaume de Falguières

- 1297–1306: Aldebert de Peyre

From 1300 to 1500

- 1306–1318: Louis de Poitiers

- 1319–1322: Guillaume de Flavacourt

- 1322–1325: Pierre de Mortemart

- 1325–1326: Pierre de Moussy

- 1326–1330: Aymar de La Voulte

- 1331–1336: Henri de Thoire-Villars

- 1336–1365: Aymar de La Voulte (again)[30]

- 1365–1373: Bertrand de Châteauneuf[31]

- 1373–1375: Pierre de Sarcenas

- 1376–1383: Bernard d'Aigrefeuille

- 1383–1385: Jean Allarmet de Brogny (Avignon Obedience)[32]

- 1385–1387: Olivier de Poitiers (Avignon Obedience).[33]

- 1387–1388: Pietro Pileo di Prata (Avignon Obedience)[34]

- 1389–1406: Guillaume de Poitiers (Avignon Obedience)[35]

- 1406–1442: Jean de Linières (Avignon Obedience)[36]

- 1442–1454: Guillaume-Olivier de Poitiers[37]

- 1454–1477: Hélie de Pompadour[38]

- 1477–1478: Giuliano della Rovere[39]

- 1478–1497: Jean de Montchenu[40]

- 1498–1542: Claude de Tournon[41]

From 1500 to 1805

- 1542–1550: Charles de Tournon[42]

- 1550–1554: Simon de Maillé-Brézé[43]

- 1554 : Cardinal Alessandro Farnese[44]

- 1554–1564: Jacques-Marie Sala[45]

- 1564–1571: Eucher de Saint-Vital[46]

- 1571–1572: Pierre V. d'Urre[47]

- 1575–1621: Jean V. de L'Hôtel[48]

- 1621–1690: Louis-François de la Baume de Suze[49]

- 1692–1713: Antoine de La Garde de Chambonas[50]

- 1713–1723: Martin de Ratabon[51]

- [1723: Etienne-Joseph I. de La Fare-Monclar][52]

- 1723–1748: François-Renaud de Villeneuve[53]

- 1748–1778: Joseph-Robin Morel de Mons[54]

- 1778–1802: Charles de La Font de Savine[55]

From 1802

- Vacancy to 1823

- 1823–1825: André Molin[56]

- 1825–1841: Abbon-Pierre-François Bonnel de la Brageresse[57]

- 1841–1857: Joseph Hippolyte Guibert[58]

- 1857–1876: Louis Delcusy[59]

- 1876–1923: Joseph-Michel-Frédéric Bonnet[60]

- 1923–1930: Etienne-Joseph Hurault

- 1931–1937: Pierre-Marie Durieux

- 1937–1965: Alfred Couderc

- 1965–1992: Jean VI. Hermil

- 1992–1998: Jean-Marie Louis Bonfils

- 1999–2015: François Marie Joseph Pascal Louis Blondel

- 2015–2023: Jean-Louis Marie Balsa

See also

References

- Duchesne, pp. 235–237.

- Bishop Venantius is claimed as a son of Sigismund the son of Gondebaud, King of Burgundy (Roche, p. 37), at least by hagiographic sources; historical sources do not mention him in that context. He was present at the Council of Epaona in September 517. He was also present at the Concilium Arvernense in November 535. Jacques Sirmond (1789). Conciliorum Galliae tam editorum quam ineditorum collectio (in Latin). Vol. Tomus primus. Paris: sumptibus P. Didot. pp. 900, 984. Venantius in Christi nomine episcopus civitatis Albensium relegi et subscripsi. Venantius in Christi nomine episcopus ecclesiae Vivariensis. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 545. Roche, I, pp. 36–43.

- It is claimed that Rusticus reigned for only nine months, following the death of Venantius. The single document referring to him has been demonstrated to be a forgery. His existence depends solely on the hagiographic Acts of Saint Venantius, where he is called a Roman, who, in his avarice, destroyed nearly all that Venantius had built. Roche, I, pp. 43–45. Acta Sanctorum Augusti Tomus II (Amsterdam 1733), pp. 103–110, at p. 109C.

- The Archdeacon Cautinus, representing of Bishop Melanius episcopus Albensium, was present at the Fifth Council of Orange in October 549. Sirmond, I, p. 1043. C. De Clercq, Concilia Galliae, A. 511 – A. 695 (Turnhout: Brepols 1963), p. 160.

- Eucherius is claimed as Helvetian royalty. His administration saw famine, flood, invasion and pillage, and a plague in the Vivarais. Roche, pp. 45–48. Gams, p. 656. Omitted by Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546.

- Firminus is said to have served for only a few weeks or months, resigning in favor of his son: Roche, pp. 48–50. Gams, p. 656. Omitted by Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546.

- Aulus was a son of Bishop Firminus, his predecessor. Roche, pp. 48–53. Gams, p. 656. Omitted by Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546.

- Eumachius: Omitted by Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546.

- Longinus: Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546.

- Joannes is known only from the Charta vetus. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546. Roche, p. 57.

- Arnulfus is known only from the Charta vetus. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546. Roche, p. 58.

- Arcontius is said by a local martyrology to have been killed by the citizens of Viviers. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 546–547. Roche, pp. 60–64.

- Nothing is known about Eribaldus for certain. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 547. Roche, p. 64. His name does not appear in the Charta vetus.

- Thomas: Gallia christiana XVI, p. 547.

- Teugrinus episcopus Albensis witnessed a grant made by Aldricus, Archbishop of Sens, at the Council of Sens ca. 833. Luc d' d' Achery (1657). Veterum aliquot scriptorum qui in Galliae Bibliothecis, maximè Benedictinorum, latuerant, Spicilegium: Tomus Secundus ... (in Latin). Paris: apud Carolum Savreux. p. 583. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 547.

- Eutherius was present at the Council of Châlons-sur-Saone in 875; in 876 at the Concilium Pontigorense; in 878 at the Council of Arles. He obtained a confirmation of the privileges of the Church of Viviers from Chales the Bald in 877: Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 548–549; and Instrumenta p. 221–222, no. 4, where he is called Hitherius. Roche, I, pp. 86–91.

- Rostaing: Roche, I, pp. 92–94.

- Richard: Roche, I, pp. 94–98.

- Thomas: Roche, I, pp. 98–104.

- Roche, I, pp. 105–107.

- Arman: Roche, I, pp. 107–110.

- Pierre: Roche, I, pp. 111–114.

- Arman: Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 550–551. Roche, I, pp. 114–118.

- Gerard: Gallia christiana XVI, p. 551. Roche, I, pp. 119–124.

- Giovanni was born in Siena, the nephew of the former Papal Legate to France, Giovanni di Toscanella. He became a protégé of Cardinal Hildebrand, later Pope Gregory VII. It was Pope Gregory, shortly after his election, who appointed Giovanni as Bishop of Viviers. He was called back to Rome in 1076, however, because of the crisis with Emperor Henry IV, and made a cardinal. Viviers was left in the care of Olivier, formerly Dean of Embrun. On the death of Gregory in 1085, Giovanni returned to Viviers. Roche, I, pp. 124–130. Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 551–552.

- Leodegarius was still alive in February 1119, since he attended Pope Calixtus II's Council of Beauvais: Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 552–554. Roche, I, pp. 130–139.

- Hatto was present at the Council of Reims in October 1119. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 554.

- Nicholas had resigned by 20 January 1205, when Pope Innocent III ordered a new bishop to be elected within eight days. A. Potthast, Regesta pontificum Romanorum Vol. I (Berlin 1874), p. 205 no. 2380. Eubel, I, p. 533 note 1.

- Bruno: Eubel, I, p. 533.

- Aymar: Roche, II, pp. 5–14.

- Bertrand: Roche, II, pp. 15–23.

- Jean Allarmet de Brogny was appointed by Clement VII on 11 August 1382. He had been Dean of the Chapter of the Cathedral of Gap. In July 1385 he was named Cardinal Priest of S. Anastasia Eubel, I, pp. 28 and 533.

- Olivier de Matrueil, Dean of Autun, was appointed Bishop of Viviers by Clement VII on 15 August 1385. He was transferred to the diocese of Châlons-sur-Saone on 29 January 1387. Eubel, I, pp. 152 and 533.

- Cardinal Pileus de Prato was Administrator, according to Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 577–578. Eubel, I, p. 23

- Guillaume was appointed on 23 December 1388. He died on 28 September 1406. Eubel, I, p. 533.

- Jean de Linieres was appointed on 19 October 1406, and consecrated on 13 March 1407. He died on 1 September 1442. Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 578–579. Eubel, I, p. 533; II, p. 269.

- Guillaume was granted his bulls of consecration and institution on 27 September 1442. He died on 16 August 1454. Eubel, II, p. 269.

- Helie had been Bishop of Alet (1448–1454). He received his bulls for Viviers on 29 November 1454. Eubel, II, p. 269.

- Cardinal della Rovere was approved on 3 December 1477. He was transferred to Mende on 3 July 1478. Eubel, II, pp. 192 and 269.

- Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 581–582. Eubel, II, p. 269.

- Claude was an illegitimate son of Guillaume V de Tournon. He had been Provost of the Church of Viviers, and was a Protonotary Apostolic. He was appointed to the Church of Viviers on 20 September 1499. Gallia christiana XVI, pp. 582–583. Eubel, II, p. 270.

- De Tournon was the grand-nephew of Claude de Tournon, and was appointed at the age of 21. He was only Administrator of Viviers until he was 27 and could be consecrated bishop. In the meantime he was studying Canon Law at Poitiers. Eubel, III, p. 336.

- De Maillé was approved by Pope Julius III on 1 September 1550. Eubel, III, p. 336.

- Alessandro Farnese, the son of Pope Paul III was appointed Administrator of the diocese of Viviers on 25 June 1554; his Administration ceased on the approval of the new bishop on 12 November 1554. Eubel, III, p. 336.

- Sala: Eubel, III, p. 336.

- Saint Vitale, a priest of Parma, was appointed on 6 September 1564, though the diocese of Viviers was in the hands of the Huguenots. He lived in Avignon, and was bishop in name only. He died on 5 January 1571. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 584. Eubel, III, p. 336.

- D'Urre was appointed on 27 August 1571, and died in 1572. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 584. Eubel, III, p. 336.

- L'Hôtel was confirmed by Pope Gregory XIII on 2 September 1575. He did not appear in Viviers until 1585. He died on 6 April 1621 at the age of 94. Gallia christiana XVI, p. 585. Eubel, III, p. 336.

- La Baume the second son of Rostaing de la Baume, Comte de Suze. was named Coadjutor Bishop and Bishop of Pompeiopolis on 13 November 1617. He succeeded to the diocese on the death of Bishop l'Hôtel on 6 April 1621. He did not participate in the Assembly of the French Clergy of 1682. La Baume died on 5 September 1690 at the age of 95. Jean, pp. 486–487. Gauchat, IV, p. 371.

- Chambonas had previously been Bishop of Lodève (1671–1692). He was nominated Bishop of Viviers by King Louis XIV on 22 September 1690, but not approved by Pope Innocent XII until 5 May 1692. During the brief pontificate of Pope Alexander VIII he had taken no action on the nomination. Chambonas therefore held only the temporalities, and was not released from Lodève until 1692. He died on 21 February 1713. Jean, p. 487. Ritzler, V, p. 246; p. 417, with note 3.

- Jean, pp. 487–488. Ritzler, V, p. 417, with note 4.

- La Fare was Abbot of Mortemer (Rouen). In February 1723 he was named Bishop of Viviers, but on 24 August was offered the diocese of Laon. He chose the latter, and was never installed in Viviers. Jean, p. 488.

- Villeneuve was a native of Aix-en-Provence. Jean, p. 488. Ritzler, V, p. 417, with note 5.

- Morel was born in Aix-en-Provence, a nephew of Bishop de Villeneuve. He obtained a Licenciate in theology (Paris). He was Vicar General of Viviers for his uncle for five years. On 9 April 1748 he was nominated by King Louis XV to be bishop of Viviers, and on 16 September his bulls were approved by Pope Benedict XIV. He was consecrated on 6 October in Paris at Saint-Sulpice by his uncle. He resigned the diocese on 29 May 1778, and died on 19 September 1783 at the age of 68. Jean, p. 488. Ritzler, VI, p. 444 with note 2.

- The son of Charles, Comte de Savine, was born in the diocese of Embrun, and obtained a Licenciate in theology (Paris). He was Vicar General of Mende for ten years. On 21 April 1778 he was nominated by King Louis XVI to be bishop of Viviers, and on 1 June his bulls were approved by Pope Pius VI. In 1791 he took the oath required of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, but when Reason replaced Religion in 1793, he was forced to flee, but was captured and imprisoned for seven months. He declined to resign at the request of Pope Pius VII in 1801, and died on 5 January 1815. Jean, pp. 488–489. Ritzler, VI, p. 444 with note 3. Roche, II, pp. 318–343.

- Société bibliographique (France) (1907). L'épiscopat français depuis le Concordat jusqu'à la Séparation (1802–1905). Paris: Librairie des Saints-Pères. p. 687.

- Brageresse: L'épiscopat français depuis le Concordat, pp. 687–688.

- Guibert: L'épiscopat français depuis le Concordat, pp. 688–689.

- Delcusy: L'épiscopat français depuis le Concordat, pp. 689–690.

- Bonnet: L'épiscopat français depuis le Concordat, p. 690.

Books

Reference works

- Gams, Pius Bonifatius (1873). Series episcoporum Ecclesiae catholicae: quotquot innotuerunt a beato Petro apostolo. Ratisbon: Typis et Sumptibus Georgii Josephi Manz. (Use with caution; obsolete)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1913). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 1 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. (in Latin)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1914). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 2 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. (in Latin)

- Eubel, Conradus (ed.); Gulik, Guilelmus (1923). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 3 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Gauchat, Patritius (Patrice) (1935). Hierarchia catholica IV (1592-1667). Münster: Libraria Regensbergiana. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1952). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi V (1667-1730). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1958). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi VI (1730-1799). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1968). Hierarchia Catholica medii et recentioris aevi sive summorum pontificum, S. R. E. cardinalium, ecclesiarum antistitum series... A pontificatu Pii PP. VII (1800) usque ad pontificatum Gregorii PP. XVI (1846) (in Latin). Vol. VII. Monasterii: Libr. Regensburgiana.

- Remigius Ritzler; Pirminus Sefrin (1978). Hierarchia catholica Medii et recentioris aevi... A Pontificatu PII PP. IX (1846) usque ad Pontificatum Leonis PP. XIII (1903) (in Latin). Vol. VIII. Il Messaggero di S. Antonio.

- Pięta, Zenon (2002). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentioris aevi... A pontificatu Pii PP. X (1903) usque ad pontificatum Benedictii PP. XV (1922) (in Latin). Vol. IX. Padua: Messagero di San Antonio. ISBN 978-88-250-1000-8.

- Sainte-Marthe, Denis de; Haureau, Bartholomaeus (1865). Gallia christiana, in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa (in Latin). Vol. Tomus sextus decimus (16). Paris: Apud V. Palme. pp. 538–610, Instrumenta, pp. 219–288.

Studies

- Du Boys, Albert (1842). Album du Vivarais, ou itinéraire historique et descriptif de cette ancienne province (in French). Grenoble: Prudhomme.

- Duchesne, Louis (1907). Fastes épiscopaux de l'ancienne Gaule (in French). Vol. Tome I: Provinces du Sud-Est (deuxieme ed.). Paris: A. Fontemoing. pp. 235–239.

- Jean, Armand (1891). Les évêques et les archevêques de France depuis 1682 jusqu'à 1801 (in French). Paris: A. Picard. pp. 486–489.

- Mollier, P. H. (1908). La cathédrale de Viviers (in French). Privas: Impr. Centr. de l'Ardéche.

- Roche, Auguste (1894). Armorial généalogique & biographique des évêques de Viviers (in French). Vol. Tome I. Lyon: M.L. Brun. Roche, Abbé Auguste (1894). Tome II.

External links

- (in French) Centre national des Archives de l'Église de France, L’Épiscopat francais depuis 1919, retrieved: 2016-12-24.