Roman Catholic Diocese of Montauban

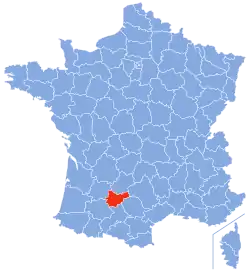

The Diocese of Montauban (Latin: Dioecesis Montis Albani; French: Diocèse de Montauban) is a Latin Church diocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese is coextensive with Tarn-et-Garonne, and is currently a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Toulouse. The episcopal seat of the Diocese of Montauban is in Montauban Cathedral.

Diocese of Montauban Dioecesis Montis Albani Diocèse de Montauban | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | France |

| Ecclesiastical province | Toulouse |

| Metropolitan | Archdiocese of Toulouse |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 3,717 km2 (1,435 sq mi) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2013) 230,800 (est.) 175,900 (est.) (76.2%) |

| Parishes | 321 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | 11 July 1317 |

| Cathedral | Cathedral of Notre Dame of the Assumption in Montauban |

| Secular priests | 59 (diocesan) 12 (Religious Orders) 9 Permanent Deacons |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Bishop | Alain Guellec |

| Metropolitan Archbishop | Guy de Kerimel |

| Bishops emeritus |

|

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| Website of the Diocese | |

Suppressed under the Concordat of 1802 and divided between the three neighbouring dioceses of Toulouse, Agen, and Cahors, Montauban was re-established by imperial decree of 1809, but this measure was not approved by the Holy See. Re-established by the Concordat of 1817, the diocese did not receive a bishop approved by the Papacy until 1824.

History

Legend attributes to Clovis the foundation of Moissac Abbey in 506, but Saint Amand (594–675) seems to have been the first abbot. The abbey grew, and in a few years its possessions extended to the gates of Toulouse. The church of Moissac, formerly the abbey church, has a portal built in 1107 which is a veritable museum of Romanesque sculpture; its cloister (1100–1108) is one of the most remarkable in France.[1]

Moissac Abbey

The threats and incursions of the Saracens, Hungarians, and Northmen brought the monks of Moissac to elect "knight abbots" who were laymen, and whose mission was to defend them. From the tenth to the thirteenth century several of the counts of Toulouse were knight-abbots of Moissac; the death of Alfonso, Count of Poitou (1271) made the King of France the legitimate successor of the counts of Toulouse, and in this way the abbey came to depend directly on the kings of France, henceforth its "knight-abbots". The union of Moissac with Cluny was begun by Abbot Stephen as early as 1047, and completed in 1063 under Abbot Durand.[2] Four filial abbeys and numerous priories depended on Moissac Abbey. In 1618 Moissac was transformed into a collegiate church which had, among other titulars, Cardinal Mazarin (1644–1661),[3] and Cardinal de Loménie de Brienne, minister of Louis XVI (1775–1788).[4]

Montauriol Abbey

In 820 Benedictine monks had founded Montauriol Abbey under the patronage of Saint Martin; subsequently, it adopted the name of its abbot Saint Theodard, Archbishop of Narbonne, who died at the abbey in 893. The Count of Toulouse, Alphonse Jourdan, took from the abbey in 1144 its lands on the heights overlooking the right bank of the Tarn, and founded there the city of Montauban; a certain number of inhabitants of Montauriol and serfs of the abbey formed the nucleus of the population. The monks protested, and in 1149 a satisfactory agreement was concluded.[5]

New ecclesiastical province

Notwithstanding the sufferings of Montauban during the Albigensian wars, the Diocese of Toulouse grew rapidly. Pope John XXII, by the Bull Salvator (25 June 1317),[6] separated the see of Toulouse from the ecclesiastical province of Narbonne, making the see of Toulouse an archiepiscopal see, and giving it four dioceses as suffragans that were created from within its territory: the Diocese of Montauban, the Diocese of St.-Papoul, the Diocese of Rieux, and the Diocese of Lombez. Bertrand de Puy, abbot at Montauriol, was first bishop of Montauban.[7] Bishop Bertrand was consecrated in Avignon on 5 August, but, as he was making his way back to his new diocese, he died on the road.[8]

From 19 January 1361 to August 1369, Montauban, which had been occupied by John Chandos, Lieutenant-General of the King Edward III of England, was in the hands of the English.[9]

Cathedral and Chapter

On 30 July 1317, in the Bull Nuper ex certis, Pope John freed the church of Montauban, which he had erected into a cathedral with a Chapter, from all other jurisdictions, in particular from the diocese of Toulouse, Cahors, Bourges, and Narbonne, and from the Benedictine Order.[10]

The monastery church of Montauriol, which became the Cathedral, had been dedicated to Saints Martin and Theodore. It was pillaged and burnt by the Protestants on 20 December 1561. Only one of the towers remained standing, and it was destroyed in 1567 for the sake of building materials for fortifications.[11] The Chapter was composed of twenty-four Canons, to which were added some sixty other clerics, variously called hebdomadaries, prebendaries, or simply clerics. The Chapter was led by a pair of 'dignities' (not dignitaries): the Provost and the Major Archdeacon.[12]

In 1630, after the destruction of the Cathedral of Saint-Martin by the Protestants, the bishop united the Chapter with the Chapter of the Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame, and that church, rededicated to Saint James, became the cathedral of the diocese.[13] In 1674, after the Huguenot Wars, when Catholics were still outnumbered by Protestants by two-to-one, the destroyed cathedral of Montauban had three dignities, three persons, and eighteen Canons.[14] The foundation stone of the present cathedral of the Assumption was laid in 1692. In 1762, the population had risen to c. 15,000, and the Cathedral boasted six dignities and eighteen Canons.[15]

There was a second Chapter in the diocese, at the Collegiate Church of Saint-Étienne de Tascon in Montaubon, headed by a Dean. It was erected into a collegiate church by Pope John XXII in 1318. Destroyed in 1561 by the Huguenots, it was reconstructed by Bishop de Colbert in 1680.[16]

Protestant ascendency

Despite the resistance of Jacques des Prés-Montpezat (1556–1589), a nephew of Jean de Lettes whom he succeeded him as bishop, the Calvinists became masters of the city; in 1561 they interdicted Catholic worship; the destruction of the churches, and even of the cathedral, was begun and carried on until 1567.[17] In 1570 Montauban became one of the four strongholds granted the Protestants and in 1578, 1579, and 1584 harboured the synods held by the députés of the Reformed Church of France.[18]

The general synod of the Reformers held at Montpellier, in May, 1598, decided on the creation of an academy at Montauban; it was opened in 1600, was exclusively Protestant, and gathered students from other countries of Europe. In 1632 the Jesuits established themselves at Montauban, but in 1659 transferred the Academy to Puylaurens.[19] In 1808 a faculty of Protestant theology was created at Montauban and still exists. By a decree of 15 September 1809, the Grand Master of the University fixed the number of professors at six.[20]

For a short time, in 1600, Catholic worship was re-established but was soon suppressed. Bishop Anne Carrion de Murviel (1600–1652), declining the honor of martyrdom, withdrew to Montech during the greater part of his reign and left his flock to be administered through deputies who did not fear the Protestants. In spite of the unsuccessful siege of Montauban by Louis XIII (August–November, 1621), the fall of La Rochelle (1629) entailed the submission of the city, and Richelieu entered it on 20 August 1629.

In 1626 the Jesuits were sent to Montauban, but in 1628 they were expelled along with all the other Catholics. They returned in 1629 after the fall of La Rochelle, but were forced to make a temporary retreat due to the plague. They were recalled in 1630 by Bishop Anne de Murviel, and they were granted half the positions in the Collège in 1633. They took over the other half when the Protestants moved to Puylaurens in 1662. They continued to staff the Collège until the Jesuits were expelled from France by edict of Louis XV on 2 February 1763.[21]

Revolution

The diocese of Montauban was one of the fifty dioceses that were abolished by decree of the National Assembly in 1790, in the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, an act which was uncanonical. The territory of the diocese, which fell into the new Department of Tarn-et-Garonne, but Montauban was not the largest city in the department, and therefore it was denied a bishop in the new Constitutional Church.

Bishop Le Tonnelier de Breteuil (1762–1794) died during the Reign of Terror on 14 August 1794, in the prison of Rouen,[22] after converting the philosopher La Harpe to Catholicism.

In 1793 the Abbey of Moissac was closed, along with all the other monastic institutions in France. The Cathedral Chapter was also disbanded.

Church of the Concordat

The diocese was recreated, uncanonically, by the Emperor Napoleon I in 1808, and he offered the diocese to Jean-Armand Chaudru de Trélissac, the pre-Revolutionary Vicar General of Montauban, who refused the offer. Other offers were made, but not confirmed by Pope Pius VII.[23]

Under the Concordat, however, Bonaparte exercised the same privileges as had the kings of France, especially that of nominating bishops for vacant dioceses, with the approval of the Pope. The practice continued until the Restoration in 1815, when the privilege of nomination returned to the hands of the King of France.[24] On the occasion of the proclamation of the Empire in 1804, Archbishop de Cicé was made a member of the Legion of Honor and a Count of the Empire.[25]

In accordance with the Concordat between Pope Pius VII and King Louis XVIII, signed on 11 June 1817, the diocese of Montauban was to be restored.[26] The Concordat, however, was never ratified by the French National Assembly, which had the reputation of being more royalist than the King, and therefore, ironically, Napoleonic legislation was never removed from the legal code (as agreed in the Concordat of 1817) and the terms of the Concordat of 1817 never became state law.

In 1881 and 1882, Jules Ferry was responsible for the enactment of the Jules Ferry Laws, establishing free primary education throughout France, and mandatory secular education. This removed church control over public education.

The low point in relations between the Vatican and Paris came in 1905, with the Law on the Separation of the Churches and the State. This meant, among other things, the end of financial support on the part of the French government and all of its subdivisions of any religious group. An inventory was ordered of all places of worship that had received subsidies from the State, and all property not legally subject to a pious foundation was to be confiscated to the State. That was a violation of the Concordat of 1801. In addition the State demanded repayment of all loans and subsidies given the Churches during the term of the Concordat. On 11 February 1906, Pope Pius X responded with the encyclical Vehementer Nos, which condemned the Law of 1905 as a unilateral abrogation of the Concordat. He wrote, "That the State must be separated from the Church is a thesis absolutely false, a most pernicious error."[27] Diplomatic relations were broken, and did not resume until 1921.[28]

After concordats

Despite huge losses in property and income, the diocese of Montauban was still able to maintain the École Saint-Théodard in Montauban for young men, and the École Jeanne-d'Arc in Montauban for young women. It also operated the Minor Seminary of the Sacred Heart, and the Institut familial.

During World War I, 109 priests and 24 seminarians participated in the conflict. 9 priests and 6 seminarians died. They won one Legion of Honor, one Médaille militaire, and 43 Croix de guerre.[29]

During World War II, Montauban was a significant transit point for persons fleeing the Nazis and the Vichy government. Bishop Théas had a well-known positive attitude toward the Jews, protesting publicly against their deportation and mistreatment. He also protested publicly against the drafting of French youth into the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO). He was arrested by the Gestapo on 9 June 1944 and interned in Toulouse; he was liberated on 30 August 1944 by the US 28th Infantry Division.[30] The socialist former Prime Minister Léon Blum recommended Montauban to Austrian socialist leaders, and Montauban had an active office of the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers), who aided in arranging passage to Spain.[31]

Religious associations

There was a convent of Cistercian monks at Belleperche (Bella pertica).[32]

The Hermits of Saint Augustine (O.E.S.A.) had a house at Montauban before 1345, headed by a Prior. The Calvinists burned the buildings on 21 August 1561, and demolished them in 1568 for building materials. They returned to Montauban in 1632, but did not recover their properties until Bishop de Bertier granted them provisionally in 1662. He also consecrated the new church in 1665.[33]

The Capuchins (O.F.M.Cap.) came to Montauban in 1629 on a preaching mission, but were driven out temporarily by the plague. In 1630 they were given property by the King and then by the consuls of Montauban, and with a gift of 6,000 livres by the Duc d'Épernon, with which they built the Hôpital-Saint-Roch, their convent and their church. The Capuchins were expelled in the anticlerical legislation of 1895-1905. and their buildings were converted for use as the diocesan Major Seminary.[34]

The Friars Minor Conventuals (Cordeliers, O.F.M.Conv.) had established themselves in Montauban before 1251, when they found themselves in trouble with Bishop Guillaume of Agen for usurping the fiefs of the Chapter, and for hearing confessions in the parishes of the city; the dispute with the Chapter continued until 1348. In the 15th century they received substantial gifts from the Seigneur de la Gravière, Notet Seguier. Along with other religious orders they were expelled by the Huguenots in 1561, and their convent was turned into a prison for a time, and then was razed to the foundations. They were restored in 1631. After they were again dissolved by the French Revolution, their buildings were occupied by the Ursulines.[35]

In 1251 the Dominicans (O.P.) established a house in Montauban in the Faubourg Saint-Étienne, colonized from their house in Cahors. A provincial Chapter was held in their convent in 1303, at which time the first Mass took place in their church. In 1561 the Calvinists seized the church and made it a Protestant house of worship, though they destroyed it in 1565 to make a fort, which was destroyed by Cardinal Richelieu in 1629, under whose protection they returned to Montauban. Another provincial Chapter of their Order took place in the new buildings in 1685. The Sisters of Mercy came to occupy the buildings after the Bourbon Restoration.[36]

The Carmelites (O.Carm.) were established in Montauban before 1277. They were expelled by the Calvinists in 1561, and when they returned in 1632, their church and their convent had completely disappeared. In 1635 they established their legal claim on the land, and rebuilt their house and a chapel.[37]

There was a convent of Clarisses (O.S.C.) as early as 1258, and the Ursulines were established in 1639. The buildings of the Clarisses were taken over by the Protestant School of Theology.[38]

On 25 July 1523, fifteen inhabitants of Moissac, after they had made a pilgrimage to Compostela, grouped themselves into a confraternity "à l'honneur de Dieu, de Notre Dame et Monseigneur Saint Jacques". This confraternity, reorganized in 1615 by letters patent of Louis XIII, existed for many years. As late as 1830 "pilgrims" were still seen in the Moissac processions. In fact Moissac and Spain were long closely united; a monk of Moissac, Gerald of Braga, was Archbishop of Braga from 1095 to 1109.

The principal pilgrimages of the diocese are: Notre Dame de Livron or de la Déliverance, visited by Blanche of Castile and Louis XIII; Notre Dame de Lorm, at Castelferrus, dating from the fifteenth century; Notre Dame de la Peyrouse, near Lafrançaise.

Among the congregations of women found in the diocese in 1913 were: Sisters of Mercy, hospitallers and teachers, founded in 1804 (mother-house at Moissac); Sisters of the Guardian Angel, hospitallers and teachers, founded in 1839 at Quillan in the Diocese of Carcassonne by Father Gabriel Deshayes, Superior of the Daughters of Wisdom,[39] whose mother-house was transferred to the château of La Molle, near Montauban in 1858.

In 2017 the diocese of Montauban was host to the following religious communities of men: the Missions Etrangères de Paris, the Ermites de Saint-Bruno, the Pères Blancs, and the Foyer d' Amitié; and the following religious communities of women: the Carmelites Missionaires, the Dominicaines de la Présentation de la Sainte Vierge, the Dominicaines du Saint Nom de Jésus, the Congregation de la Sainte-Famille, the Soeurs de la Miséricorde, the Soeurs de l'Ange Gardien, the Ursulines de l'Union Romaine and the Communauté Marie Mère de l'Eglise.[40]

Bishops

from 1317 to 1519

- 1317 : Bertrand (I) du Puy, O.S.B.[41]

- 1317–1355 : Guillaume de Cardaillac[42]

- 1355–1357 : Jacques (I) de Daux (Deaulx)[43]

- 1357–1361 : Bertrand (II) de Cardaillac[44]

- 1361–1368 : Arnaud Bernardi du Pouget (Administrator)[45]

- 1368–1379 : Pierre (I) de Chalais[46]

- 1380–1403 : Bertrand (III) Robert de Saint-Jal (Avignon Obedience)[47]

- 1403–1404 : Géraud du Puy[48]

- 1404–1424 : Raymond de Bar[49]

- 1424–1425 : Gérard de Faidit[50]

- 1425–1427 : Pierre de Cottines[51]

- 1427–1445 : Bernard de la Roche Fontenilles, O.Min.[52]

- 1446–1449 : Aymery de Roquemaurel[53]

- 1450–1452 : Bernard de Rousergues[54]

- 1452–1453 : Guillaume d'Estampes[55]

- 1454–1470 : Jean de Batut de Montrosier[56]

- 1470–1484 : Jean de Montalembert, O.S.B.Clun.[57]

- 1484 : Georges de Viguerie[58]

- 1484–1491 : Georges d'Amboise[59]

- 1491–1519 : Jean d'Auriolle[60]

from 1519 to 1800

- 1519–1539 : Jean des Prés-Montpezat[61]

- 1539–1556 : Jean de Lettes-Montpezat[62]

- 1556–1589 : Jacques II des Prés-Montpezat[63]

- 1600–1652 : Anne Carrion de Murviel[66]

- 1652–1674 : Pierre de Bertier[67]

- 1675–1693 : Jean-Baptiste Michel de Colbert[68]

- 1693–1703 : Henri de Nesmond[69]

- 1703–1728 : François d'Haussonville de Nettancourt Vaubecourt[70]

- 1728–1763 : Michel de Verthamon de Chavagnac[71]

- 1763–1794 : Anne-François Victor le Tonnelier de Breteuil[72]

- 1794–1817 : Sede Vacante

since 1800

- 1817–1824 : Jean-Armand Chaudru de Trélissac, administrator[73]

- 1824–1826 : Jean-Louis Lefebvre de Cheverus[74]

- 1826–1833 : Louis-Guillaume-Valentin DuBourg[75]

- 1833–1844 : Jean-Armand Chaudru de Trelissac[76]

- 1844–1871 : Jean-Marie Doney[77]

- 1871–1882 : Théodore Legain[78]

- 1882–1908 : Adolphe-Josué-Frédéric Fiard[79]

- 1908–1929 : Pierre-Eugène-Alexandre Marty[80]

- 1929–1935 : Clément Émile Roques

- 1935–1940 : Elie-Antoine Durand

- 1940–1947 : Pierre-Marie Théas[30]

- 1947–1970 : Louis de Courrèges d'Ustou

- 1970–1975 : Roger Tort

- 1975–1996 : Jacques de Saint-Blanquat

- 1996–2007 : Bernard Housset

- 2007–2022 : Bernard Ginoux[81]

- 2022–present : Alain Guellec

See also

References

- Quitterie Cazes; Maurice Scellès (2001). Le cloître de Moissac (in French). Bordeaux: Éditions Sud Ouest. ISBN 978-2-87901-452-4.

- Ernest Rupin (1897). L'abbaye et les cloîtres de Moissac (in French). Paris: A. Picard. pp. 13–24, 45–57 (Durand).

- Rupin, pp. 170–172

- Daux, II, p. 73. Rupin, pp. 179-180.

- Claude Devic; Lucas (1733). Histoire générale de Languedoc avec des notes et les pièces justificatives (in French). Vol. Tome second. Paris: chez Jacques Vincent. pp. 438, 463.

- Tomassetti, Luigi, ed. (1859). Bullarum. diplomatum et privilegiorum sanctorum romanorum pontificum. Vol. Tomus IV. (Taurinensis ed.). Turin: Seb. Franco et Henrico Dalmazzo editoribus. pp. 245–247.

- Daux, pp. 11-16.

- The fact is recalled by Pope John XXII in his letter of appointment of the second bishop, Guillaume. Daux, pp. 23-24, with note 2.

- Moulenq, pp. 78-79.

- Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, Instrumenta, p. 203.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 83-84.

- Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 225-228.

- Moulenq, II, p. 97.

- Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 273 note 1. There were 1300 Catholics and 2600 Protestants.

- Ritzler-Sefrin, VI, p. 294. The diocese contained 183 parishes.

- Moulenq, p. 89.

- Moulenq, p. 69.

- Philip Conner (2017). "Chapter 4: Montauban as a 'mother' church". Huguenot Heartland: Montauban and Southern French Calvinism During the Wars of Religion. New York NY USA: Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-92995-0.

- Michel Nicolas (1885). Histoire de l'ancienne Académie protestante de Montauban (1598-1659) et de Puylaurens (1660-1685) (in French). Montauban: Impr, et lithographie E. Forestié. pp. 5–13.

- Charles Louis Frossard (1882). Les origines de la faculté de théologie protestante de Montauban: étude historique ... (in French). Paris: Grassart. pp. 20–21.

- Moulenq, p. 112.

- Jean, p. 397.

- Paul Poupard (1961). Correspondence inédite entre Mgr. Antonio Garibaldi, internonce à Paris, et Mgr. Cesaire Mathieu, Archévêque de Besançon (in French). Rome: Gregorian Biblical BookShop. pp. 123, note 11. ISBN 978-88-7652-624-4. See also the remarks of C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., p. 363.

- Georges Desdevises du Dezert (1908). L'église & l'état en France ...: Depuis le Concordat jusqu' nos jours (1801-1906) (in French). Paris: Société Française d'Imprimerie et de Libraire. pp. 21–22.

- Palanque, p. 177.

- Concordat entre Notre Saint Père le pape et le roi très-chrétien, signé à Rome, le 11 juin 1817: avec les bulles et pièces qui y sont relatives, en latin & en françois, et la liste des évêques de France (in French and Latin). Paris: A. Le Clère. 1817. pp. 37, 43, 84.

- Ceslas B. Bourdin, "Church and State" in: Craig Steven Titus, ed. (2009). Philosophical Psychology: Psychology, Emotions, and Freedom. Washington DC USA: CUA Press. pp. 140–147. ISBN 978-0-9773103-6-4.

- J. de Fabregues (1967). "The Re-Establishment of Relations between France and the Vatican in 1921". Journal of Contemporary History. 2 (4): 163–182. doi:10.1177/002200946700200412. JSTOR 259828. S2CID 220874600.

- A. Baudrillart, ed. (1920). Almanach catholique français pour 1920 (in French). Paris: Bloud & Gay. p. 89.

- Diocèse de Montauban, Mgr. Théas; retrieved: 2017-11-20. (in French) Anonymes, Justes et Persécutés durant la période Nazie dans les communes de France, Juste parmi les Nations: Pierre-Marie Théas; retrieved: 2017-11-20. (in French)

- Bension Varon (2015). Fighting Fascism and Surviving Buchenwald: The Life and Memoir of Hans Bergas. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 21–25. ISBN 978-1-5035-7255-3.

- Jean, p. 397. Association des amis de Belleperche (1999). La grande aventure des Cisterciens: leur implantation en Midi-Pyrénées : actes du Colloque organisé à l'Abbaye de Belleperche, les 22 et 23 août 1998 (in French). Montauban: Ove design & éditions. ISBN 9782951462106.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 100-101.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 101-102.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 103-105.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 105-107.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 102-103.

- Moulenq, II, pp. 109-112.

- F. Laveau (1854). Vie du P. Deshayes ancien recteur d'auray, Et vicaire-général de Vannes (in French). Vannes: Gustave de Lamarzelle. J. F. Devaux, Les Filles de la Sagesse II (Cholet 1955). A. P. Laveille, C. Collin, G. Deshayes et ses familles religieuses..(Brussels 1924).

- Diocèse de Montauban, Vie consacrée; retrieved: 2017-11-22. (in French)

- Bertrand was granted his bulls on 5 August 1317. He was never installed. Eubel, I, p. 347.

- Guillaume was appointed by Pope John XXII on 12 November 1317. He had been Abbot of the Benedictine monstery of Pessan (diocese of Auch). He died in 1355. Daux, pp. 23-70. Eubel, I, p. 347.

- Jacques de Daux was the nephew of Cardinal Bertrand de Deaulx, and had been Canon and Sacristan of the Cathedral Chapter of Avignon. He was a doctor of canon law. He was appointed by Pope Innocent VI on 10 June 1355 (not on 24 December, as in Gams, p. 578). He was transferred to the diocese of Gap on 21 August 1357, and then to Nîmes on 6 April 1362. Joseph Hyacinthe Albanès (1899). Gallia christiana novissima (in French and Latin). Vol. Tome premier: Aix, Apt, Frejus, Gap, Riez, et Sisteron. Montbéliard: Société anonyme d'Imprimérie Montbéliardaise. pp. 501–502, Instrumenta, pp. 319–320, no. LIV. Eubel, I, p. 347, 361, 514.

- Bertrand was the nephew of Bishop Guillaume de Cardaillac, and the brother of Archbishop Jean, titular Patriarch of Alexandria. He was appointed by Pope Innocent VI on 21 August 1357, the same day as Bishop Jacques de Deaulx was transferred to Gap. Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 236-237. Eubel, I, p. 347. (There was no 'Bishop Bernardus'; he is a mistake for Bertrandus. There was no Sede Vacante, as is sometimes claimed).

- Arnaldus was appointed Administrator of the diocese of Montauban by Pope Innocent VI on 16 June 1361. He was named a cardinal by Pope Urban V on 22 September 1368, but died before he could be assigned a title. Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 237-238. Eubel, I, pp. 21, 347.

- Pierre was appointed by Pope Urban V on 18 October 1368. He died on 22 November 1379. Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 238-239. Eubel, I, p. 347.

- Bertrand was appointed on 14 January 1380 by Pope Clement VII. He died on 5 (or 8) September 1403. Gallia christiana XIII, p. 239-240. Eubel, I, p. 347.

- Bishop du Puy was appointed on 27 September 1403 by Pope Benedict XIII. He took possession through procurators, and governed through two Vicars who were members of the Cathedral Chapter. Gerard was transferred to the diocese of Saint Flour on 17 December 1404. Gallia christiana XIII, p. 240. Eubel, I, pp. 251, 347.

- Raymond had held the office of Dean of the Cathedral Chapter of Gap. He was appointed to the diocese of Montauban on 17 December 1404 by Benedict XIII. He resigned, or died, on 26 March 1424. Gallia christiana XIII, p. 241. Eubel, I, p. 347.

- Bishop Faidit had been Cantor in the Cathedral Chapter of Lavaur. He was appointed Bishop of Montauban by Pope Martin V on 5 June 1424. He was transferred to the diocese of Couserans on 10 September 1425. Eubel, I, pp. 204, 347.

- Pierre de Cottines was appointed Bishop of Montauban on 28 September 1425 by Pope Martin V. He was transferred to the diocese of Castres on 24 October 1427. Eubel, I, p. 173, 347.

- Bernard de la Roche had been Bishop of Cavaillon (1424–1427). He received his bulls for Montauban on 24 October 1427, but did not enter his diocese until 29 September 1429; he stayed for two years in Beaumont-de-Lomagne. He signed his Testament in Paris on 23 September 1445, dying shortly thereafter. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, p. 242. Eubel, I, p. 179 and 347; II, p. 195.

- Aimeric had been Prior Major of the Cathedral of Montauban and Abbot of Moissiac. He paid for his bulls on 7 January 1446. He died on 16 October 1449. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 242-243. Eubel, II, p. 195.

- Bernard Rosier had been Bishop of Bazas (1447–1450). He was requested by the Church of Montauban, and provided by Pope Nicholas V on 9 January 1450. He was transferred to the diocese of Toulouse on 3 January 1452. Eubel, II, pp. 252, 263, 347.

- Guillaume d'Estampes received his bulls on 3 January 1452. His brother Robert was Marshal and Seneschal of Bourbon, and his brother Jean was Bishop of Carcassonne. As Bishop-elect he was sent as ambassador by King Charles VII of France to Alfonso of Aragon, and then to Frederick, King of the Romans. Guillaume was transferred to the diocese of Condom on 18 March 1454. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, p. 243. Eubel, II, pp. 133, 195.

- Montrosier was given his bulls by Pope Nicholas V on 8 March 1454 (according to Sainte-Marthe; or 29 March, according to Garampi), and took possession on 18 November 1455. He died in 1470. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, p. 244. Eubel, II, p. 195.

- Montalambert was elected by the Chapter, and confirmed by Archbishop Bernard of Toulouse on 23 August 1470. He was confirmed by Pope Paul II on 1 July 1471, and his bulls were issued on 5 July 1471. He died in 1483. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, p. 244. Eubel, II, p. 195.

- Viguerie was Aumonier of the Chapter of the Cathedral of Montauban, and was elected by them as bishop, but he died before 7 May without having received papal approval. Jean de Brugeres, the Cantor of the Chapter of Rodez, was offered the bishopric by the Chapter, but he declined. The Chapter then turned to Jean de Saint Estienne. On 16 December 1484, Pope Innocent VIII wrote to Montauban to admit Georges d'Amboise as their bishop, but Jean de Saint Estienne opposed him into 1485, when he died. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, p. 245. Eubel, II, p. 195.

- Georges d'Amboise was appointed bishop at the age of fourteen in 1484. He was consecrated a bishop in 1489. He made his solemn entry into his diocese on 10 May 1489. He was transferred to the diocese of Narbonne on 2 December 1491. He was named a cardinal on 17 September 1498. He was minister of Louis XII, and twice in 1503 embarrassed himself by trying to intimidate a conclave into electing him pope. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, p. 245. Eubel, II, p. 195.

- Jean d'Auriole was the son of Pierre d'Auriole, Chancellor of France of King Louis XII. He was named bishop of Montauban in Consistory by Pope Innocent VIII on 2 December 1491. He died on 21 October 1519. According to Daux, I, Deuxième periode: Jean d' Oriolle, p. 52, Auriole gave up the administration of his diocese on 15 or 21 July 1516, in favor of his nephew, Antoine, who was a Canon of Cahors. His Testament is dated 3 February 1518 (Daux, p. 56). Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 245-247. Eubel, II, p. 195.

- Daux, I, Deuxième periode: Jean d' Oriolle, p. 46, argues that Jean des Prés was Coadjutor for Bishop d'Auriole from 1516. Eubel, III, p. 248, dates his episcopacy from 31 May 1516, citing Garampi as his source. Bishop des Prés died on 30 October 1539.

- Jean de Lettes was Abbot of Moissac and Bishop of Béziers (1537-1543), which he was allowed to keep along with the Bishopric of Montauban with royal and papal permission down until October 1543. He was approved as Bishop of Montauban by Pope Paul III on 20 November 1537. He resigned the Abbey of Moissac to Cardinal de Guise, and the bishopric of Montauban to his nephew Jacques. He married and became a Protestant. Sainte-Marthe, Gallia christiana XIII, pp. 249-250. Le Bret, II, pp. 6-7. Eubel, III, p. 248.

- Des Prés was approved in Consistory by Pope Paul IV on 12 June 1556. He died on 25 January 1589. Eubel, III, p. 248.

- Daux, II, Troisième période, Vacance du Siége, p. 95. Eubel, III, p. 248.

- Claude de Champaigne had been Grand Vicar for Bishop Jacqaues des Pres. On the bishop's death, Claude was elected Vicar Capitular by the Chapter. He was Vicar in spiritualities, but he was not a bishop and did not perform functions reserved for a bishop. The Chapter also elected a Vicar for temporalities, François de Prévost. Gallia christiana XIII, p. 251. Daux, II, Troisième période, Vacance du Siége, pp. 95-98.

- De Murviel was approved on 15 November 1600 by Pope Clement VIII. He was assigned a Coadjutor bishop on 7 April 1636. He died on 8 September 1652. Eubel, III, p. 248. Gauchat, Hierarchia catholica IV, p. 246.

- Pierre de Berthier (as he signed himself) was named titular bishop of Augustopolis and Coadjutor Bishop of Montaubon on 7 April 1636 by Pope Urban VIII. He succeeded to the bishopric on 8 September 1652, and died in June 1674. Gauchat, p. 101 with note 7; 246.

- Colbert was nominated by King Louis XIV on 21 November 1674, and preconised (approved) by Pope Clement X on 15 July 1675. He was transferred to the diocese of Toulouse on 12 October 1693. Jean, p. 395. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 273 with note 3.

- Nesmond was named Bishop of Montauban by Louis XIV in 1687, to succeed Colbert, who was to be promoted to Toulouse. Pope Innocent XI, however, was unwilling to issue bulls of transfer for Colbert, or bulls of consecration and institution for Nesmond, due to the breakdown in relations between the Papacy and Louis XIV, over the Four Articles. Innocent XI died in 1689, but his successor, Alexander VIII held the same position, and therefore it was not until Louis XIV made his retraction in 1692 that the Pope was willing to sign bulls for the two prelates. In the meantime, Nesmond served as Vicar General for Bishop Colbert. Nesmond was finally consecrated on 24 May 1693 by Bishop Charles-Antoine de la Garde de Chambonas of Viviers. Jean, p. 395-396. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 273 with note 4.

- Vaubecourt: Jean, p. 395. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 273 with note 5.

- Verthamon was nephew of Jean-Jacques de Verthamon, Bishop of Couserans; brother of Guillaume-Samuel de Verthamon, Bishop of Luçon; and cousin of and Jean-Baptiste de Verthamon, Bishop of Pamiers; one of his uncles was Pierre de Verthamon, S.J., Provincial of France. Michel was consecrated a bishop in Paris on 8 January 1730. He died at Montaubon on 25 September 1762. Jean, p. 396. Ritzler-Sefrin, V, p. 273 with note 6.

- Born in Paris in 1724, Breteuil had been Canon of Soissons and Vicar General of Narbonne for five years. He was nominated by King Louis XV on 10 October 1762, and preconised by Pope Clement XIII on 24 January 1763. He was consecrated on 24 February 1763 by Archbishop Charles de la Roche-Aymon of Reims. He was imprisoned under the French Terror and died on 14 August 1794. Jean, pp. 396-397. Ritzler-Sefrin, VI, p. 294 with note 2.

- Chaudru de Trélissac had been Vicar General of Montauban before the Revolution. C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., p. 363. Ritzler-Sefrin, VII, p. 269.

- Cheverus was transferred from the diocese of Boston, Massachusetts on 3 May 1824. Cheverus became Archbishop of Bordeaux and a cardinal. He died in 1836. Annuario pontificio (Roma: Cracas 1826), p. 94. André Hamon, Vie du cardinal de Cheverus, archevèque de Bordeaux quatrième édition (Paris 1837). C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., pp. 363-364. Ritzler-Sefrin, VII, p. 269.

- Dubourg: C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., pp. 364-365. Annabelle McConnell Melville (1986). Louis William DuBourg: Bishop in two worlds, 1818-1833. Chicago: Loyola University Press. ISBN 978-0-8294-0529-3. Ritzler-Sefrin, VII, p. 269.

- Chaudru de Trelissac: C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., pp. 365-366. Ritzler-Sefrin, VII, p. 269.

- Doney was named by the French government on 28 November 1843, and preconsied by Pope Gregory XVI on 22 January 1844. He was consecrated a bishop on 15 March 1844 by Archbishop Jacques Mathieu of Besançon. In 1866 Doney made a spectacle of himself by writing a furious letter to the French newspaper Le Monde, in which he denounced an ecumenical project to translate the Bible into French, on the grounds that it was repugnant to the principles of the Catholic Church, contrary to the decrees of Councils and of Popes, contrary to common sense, and an act of rebellion and impiety on the part of priests who joined the group. Evangelical Christendom. new series. Vol. VII. London: W. J. Johnson. 1866. p. 221. In 1869 Doney attended the First Vatican Council. He died on 21 January 1871. In general see: C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., pp. 366-367. Ritzler-Sefrin, VIII, p. 392.

- Legain: C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., pp. 368-369. Ritzler-Sefrin, VIII, p. 392.

- Fiard was a native of Lens-Lestang (diocese of Valence). He served as Vicar-General of Oran, and was appointed bishop of Montauban on 18 November 1881. He was consecrated at Montauban on 25 January 1882. C. Daux, in: Société bibliographique (France) (1907), L'épiscopat français..., p. 369. A. Battandier (ed.), Annuaire pontifical catholique (Paris: Maison de la Bonne Presse 1907), p. 261.(in French)

- Marty was born in 1850 in Beaumont-de-Perigord. He studied at the Minor Seminary of Bergerac, at the Major Seminary of Périgueux, and then at the Institut Catholique de Toulouse. He was appointed teacher of dogma at the seminary of Toulouse. In 1888 he was awarded a Canonry in the Cathedral, and he became a visiting preacher in several dioceses in France. Bishop Fiard of Montauban asked Pope Pius X specifically to name Marty as his successor. The Pope appointed Marty as Coadjutor Bishop on 7 August 1907, and he succeeded to the diocese on 10 January 1908. He died on 3 February 1929. J. P. Poey (1908). Évêques de France: biographies et portraits de tous les cardinaux, archevêques et évêques de France et des colonies (in French) (third ed.). Paris: P. Lethielleux. pp. 168–169. A. Baudrillart, ed. (1920). Almanach catholique français pour 1920 (in French). Paris: Bloud & Gay. p. 89.

- Diocèse de Montauban, Mgr. Bernard Ginoux, retrieved: 2017-11-17. (in French)

Bibliography

- Reference books

- Gams, Pius Bonifatius (1873). Series episcoporum Ecclesiae catholicae: quotquot innotuerunt a beato Petro apostolo. Ratisbon: Typis et Sumptibus Georgii Josephi Manz. pp. 479–480. (Use with caution; obsolete)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1913). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 1 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. pp. 76–77. (in Latin)

- Eubel, Conradus, ed. (1914). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 2 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana. p. .

- Eubel, Conradus (ed.); Gulik, Guilelmus (1923). Hierarchia catholica, Tomus 3 (second ed.). Münster: Libreria Regensbergiana.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) p. . - Gauchat, Patritius (Patrice) (1935). Hierarchia catholica IV (1592-1667). Münster: Libraria Regensbergiana. Retrieved 2016-07-06. p. .

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1952). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi V (1667-1730). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 2016-07-06. p. .

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1958). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentis aevi VI (1730-1799). Patavii: Messagero di S. Antonio. Retrieved 2016-07-06. pp. .

- Ritzler, Remigius; Sefrin, Pirminus (1968). Hierarchia Catholica medii et recentioris aevi sive summorum pontificum, S. R. E. cardinalium, ecclesiarum antistitum series... A pontificatu Pii PP. VII (1800) usque ad pontificatum Gregorii PP. XVI (1846) (in Latin). Vol. VII. Monasterii: Libr. Regensburgiana.

- Remigius Ritzler; Pirminus Sefrin (1978). Hierarchia catholica Medii et recentioris aevi... A Pontificatu PII PP. IX (1846) usque ad Pontificatum Leonis PP. XIII (1903) (in Latin). Vol. VIII. Il Messaggero di S. Antonio.

- Pięta, Zenon (2002). Hierarchia catholica medii et recentioris aevi... A pontificatu Pii PP. X (1903) usque ad pontificatum Benedictii PP. XV (1922) (in Latin). Vol. IX. Padua: Messagero di San Antonio. ISBN 978-88-250-1000-8.

- Studies

- Darrow, Margaret H. (2014). "Chapter Two: Montauban in Revolution". Revolution in the House: Family, Class, and Inheritance in Southern France, 1775-1825. Princeton University Press. pp. 20–54. ISBN 978-1-4008-6034-0.

- Daux, Camille (1881). Histoire de l'église de Montauban (in French). Vol. Tome premier. Montauban: Bray et Retaux. [Pagination is not continuous, but begins anew with each 'Period'. The biography of each bishop was issued separately, each with its own pagination.]

- Daux, Camille (1882). Histoire de l'église de Montauban (in French). Vol. Tome II. Montauban: Bray et Retaux.

- De Vic, Cl.; Vaissete, J. (1876). Histoire generale de Languedoc (in French). Vol. Tome IV. Toulouse: Edouard Privat.

- Jean, Armand (1891). Les évêques et les archevêques de France depuis 1682 jusqu'à 1801 (in French). Paris: A. Picard. pp. 395–397.

- Le Bret, Henry (1841). Marcellin et Gabriel Ruck (ed.). Histoire de Montauban (in French). Vol. Tome premier (nouvelle ed.). Montauban: chez Rhetoré.

- Ligou, Daniel (1954). "La structure sociale du Protestantisme Montalbanais à la fin du XVIIIe siècle," Bulletin de la Société de l'histoire du Protestantisme français 100 (1954), pp. 93–110. (in French)

- Moulenq, François (1880). Documents historiques sur le Tarn-et-Garonne, diocése, abbayes, chapitres, commanderies, églises, seigneuries, etc (in French). Vol. Tome second. Montauban: Forestie.

- Sainte-Marthe, Denis de (1785). Gallia christiana, in provincias ecclesiasticas distributa (in Latin). Vol. Tomus decimus-tertius (13) (second ed.). Paris: Johannes- Baptista Coignard. pp. 226–266, Instrumenta, pp. 181–220.

- Société bibliographique (France) (1907). L'épiscopat français depuis le Concordat jusqu'à la Séparation (1802-1905). Paris: Librairie des Saints-Pères.

External links

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Montauban". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Montauban". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Montauban". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Diocese of Montauban". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.