Bagha Jatin

Bagha Jatin (lit. 'Tiger Jatin'; pronounced [ˈbaɡʰa ˈd͡ʒot̪in]) or Baghajatin, born Jatindranath Mukherjee (pronounced [ˈd͡ʒot̪ind̪roˌnatʰ ˈmukʰoˌpaddʰaj]); 7 December 1879 – 10 September 1915) was an Indian independence activist.[1][2]

Baghajatin | |

|---|---|

Jatindranath Mukherjee | |

| Born | 7 December 1879 Kayagram village, Kushtia subdivision, Nadia district, Bengal Presidency, British India (now in Kumarkhali, Kushtia District, Bangladesh) |

| Died | 10 September 1915 (aged 35) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Other names | Bagha Jatin |

| Education | University of Calcutta |

| Occupation | Indian independence activist |

| Organisation | Jugantar |

| Known for | Freedom Struggle |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

| Anushilan Samiti |

|---|

|

| Influence |

| Anushilan Samiti |

| Notable events |

| Related topics |

He was one of the principal leaders of the Jugantar party that was the central association of revolutionary independence activists in Bengal.[3][4]

Early life

Jatin was born in a Brahmin family[5] to Sharatshashi and Umeshchandra Mukherjee in Kayagram, a village in the Kushtia subdivision of undivided Nadia district, in what is now Bangladesh, on 7 December 1879. He grew up in his ancestral home at Sadhuhati, P.S. Rishkhali, Jhenaidah until his father's death when Jatin was five years old. Well versed in Brahmanic studies, his father liked horses and was respected for the strength of his character. Sharatshashi settled in her parents' home in Kayagram with her son and his elder sister Benodebala (or Vinodebala). A gifted poet, she was affectionate and stern in her method of raising her children. Familiar with the essays by contemporary thought leaders like Bankimchandra Chatterjee and Yogendra Vidyabhushan, she was aware of the social and political transformations of her times. Her brother Basanta Kumar Chattopadhyay (father of Indian revolutionary and politician Haripada Chattopadhyay) taught and practised law, and counted among his clients the poet Rabindranath Tagore. Since the age of 14, Tagore had claimed in meetings organised by his family members equal rights for Indian citizens inside railway carriages and in public places. As Jatin grew older, he gained a reputation for physical bravery and great strength; charitable and cheerful by nature, he was fond of caricature and enacting religious plays, himself playing the roles of god-loving characters like Prahlad, Dhruva, Hanuman, Râja Harish Chandra as well as courageous personalities like Pratapaditya. He not only encouraged several playwrights to produce patriotic pieces for the urban stage, but also engaged village bards to spread nationalist fervour in the countryside.[6]

Student in Calcutta

After passing the Entrance examination in 1895 from Krishnanagar Anglo-vernacular School (A.V. School), Jatin joined the Calcutta Central College (now Khudiram Bose College), to study Fine Arts. At the same time, he took lessons in steno typing with Mr. Atkinson. This was a new qualification opening the possibilities of a coveted career. Soon he started visiting Swami Vivekananda, whose social thought, and especially his vision of a politically independent India – indispensable for the spiritual progress of humanity – had a great influence on Jatin. The Master taught him the art of conquering libido before raising a batch of young volunteers "with iron muscles and nerves of steel", to serve miserable compatriots during famines, epidemics and floods and running clubs for "man-making" in the context of a nation under foreign domination. They soon assisted Sister Nivedita, the Swami's Irish disciple, in this venture. According to J. E. Armstrong, Superintendent of the colonial Police, Jatin "owed his preeminent position in revolutionary circles, not only to his qualities of leadership, but in great measure to his reputation of being a Brahmachari with no thought beyond the revolutionary cause."[7] Noticing his ardent desire to die for a cause, Swami Vivekananda sent Jatin to the Gymnasium of Ambu Guha where he himself had practised wrestling. Jatin met here, among others, Sachin Banerjee, son of Yogendra Vidyabhushan (a popular author of biographies like Mazzini and Garibaldi), who turned into Jatin's mentor. In 1900, his uncle Lalit Kumar married Vidyabhushan's daughter.

Fed up with the colonial system of education, Jatin left for Muzaffarpore in 1899, as secretary of barrister Pringle Kennedy, founder and editor of the Trihoot Courrier.[8] He was impressed by this historian; through his editorials and from the Congress platform, he showed how urgent it was to have an Indian National Army and to react against the British squandering of Indian budget to safeguard their interests in China and elsewhere.

Marriage

In 1900, Jatin married Indubala Banerjee of Kumarkhali upazila in Kushtia; they had four children: Atindra (1903–1906), Ashalata (1907–1976), Tejendra (1909–1989), and Birendra (1913–1991). Struck by Atindra’s death, Jatin, with his wife and sister, set out on a pilgrimage and recovered their inner peace by receiving initiation from the saint Bholanand Giri of Haridwar. Aware of his disciple’s revolutionary commitments, the holy man extended to him his full support.

Title Bagha Jatin

Upon returning to his native village Koya in March 1906, Jatin learned about the disturbing presence of a tiger in the vicinity; while scouting in the nearby jungle, he came across a Royal Bengal tiger and fought hand-to-hand with it. Wounded, he managed to strike with a Small dagger (Khukuri) on the tiger's neck, killing it instantly. The famous surgeon of Calcutta, Suresh Prasad Sarbadhikari, "took upon himself the responsibility for curing ... [Jatin,] whose whole body had been poisoned by the tiger's nails."[9] Impressed by Jatin's exemplary heroism, Dr. Sarbadhikari published an article about Jatin in the English press. The Government of Bengal awarded him a silver shield with the scene of him killing the tiger engraved on it.[10] The title 'Bagha', meaning 'Tiger' in Bengali, became associated with him since then.

Revolutionary activities

Several sources mention Jatin as being among the founders of the Anushilan Samiti in 1902, and as a pioneer in creating its branches in the districts. According to Daly's Report: "A secret meeting was held in Calcutta about the year 1900 [...] The meeting resolved to start secret societies with the object of assassinating officials and supporters of Government [...] One of the first to flourish was at Kushtea, in the Nadia district. This was organised by one Jotindra Nath Mukherjee [sic!].".[11] Nixon reports further: "The earliest known attempts in Bengal to promote societies for political or semi-political ends are associated with the names of the late P. Mitter, Barrister-at-Law, Miss Saralabala Ghosal and a Japanese named Okakura. These activities commenced in Calcutta somewhere about the year 1900, and are said to have spread to many of the districts of Bengal and to have flourished particularly at Kushtia, where Jatindra Nath Mukharji [sic!] was leader."[12] Bhavabhushan Mitra's written notes precise his presence along with Jatindra Nath during the first meeting. A branch of this organisation (Anushilan Samiti), was to be inaugurated in Dacca. In 1903, on meeting Sri Aurobindo at Yogendra Vidyabhushan's place, Jatin decides to collaborate with him and is said to have added to his programme the clause of winning over the Indian soldiers of the British regiments in favour of an insurrection. W. Sealy in his report on "Connections with Bihar and Orissa" notes that Jatin Mukherjee "a close confederate of Nani Gopal Sen Gupta of the Howrah Gang (...) worked directly under the orders of Aurobindo Ghosh."[13]

In 1905, during a procession to celebrate the visit of the Prince of Wales at Calcutta, Jatin decides to draw the attention of the future Emperor on the behaviour of HM's English officers. Not far from the royal coach, he singles out a cabriolet on a side-lane, with a group of English military men sitting on its roof, their booted legs dangling against the windows, seriously disturbing the livid faces of a few native ladies. Stopping beside the cab, Jatin asks the fellows to leave the ladies alone. In response to their cheeky provocation, Jatin rushes up to the roof and fell them with slaps till they drop on the ground.[14] The show is not innocent. Jatin is well aware that John Morley, the Secretary of State, receives regularly complaints about the English attitude towards Indian citizens, "The use of rough language and pretty free use of whips and sticks, and brutalities of that sort..." He will be further intimated that the Prince of Wales, "on his return from the Indian tour had a long conversation with Morley [10/5/1906] (...) He spoke of the ungracious bearing of Europeans to Indians."[15]

Organiser of secret society

Jatin, together with Barindra Ghosh, set up a bomb factory near Deoghar, while Barin was to do the same at Maniktala in Calcutta. Whereas Jatin disapproved of all untimely terrorist action, Barin led an organisation centred around his own personality: his aim was, aside from the general production of terror, the elimination of certain Indian and British officers serving the Crown. Side by side, Jatin developed a decentralised federated body of loose autonomous regional cells. Organising relentless relief missions with a paramedical body of volunteers following almost a military discipline, during natural calamities such as floods, epidemics, or religious congregations like the Ardhodaya and the Kumbha Mela, or the annual celebration of Ramakrishna's birth, Jatin was suspected of utilising these as pretexts for group discussions with regional leaders and recruiting new freedom fighters to fight the supporters of the Britain.[16][17]

In May 1907 he was deputed as a shorthand writer to Mr. O'Malley's Office in Darjeeling for the Gazetteer work.[4] "From early youth he had the reputation of a local Sandow and he soon attracted attention in Darjeeling in cases in which (...) he tried to measure the strength with Europeans. In 1908 he was leader of one of several gangs that had sprung up in Darjeeling, whose object was the spreading of disaffection, and with his associates he started a branch of the Anushilan Samiti, called the Bandhab Samiti."[18] In April 1908, in Siliguri railway station, Jatin got involved in a fight with a group of English military officers headed by Captain Murphy and Lt Somerville, leading to legal proceedings, widely covered by the press.[19] On observing the gleeful animosity created by the news of a few Englishmen thrashed single-handed by an Indian, Wheeler advised the officers to withdraw the case. Warned by the Magistrate to behave properly in the future, Jatin regretted that he would not refrain from taking similar action in self-defence or in the vindication of the rights of his countrymen.[20] One day, in a pleasant mood, Wheeler asked Jatin : "With how many can you fight all alone ?" The prompt reply was: "Not a single one, if it is a question of honest people; otherwise, as many as you can imagine!"[21] In 1908 Jatin was not one of over thirty revolutionaries accused in the Alipore Bomb Case following the incident at Muzaffarpur. Hence, during the Alipore trial, Jatin took over the leadership of the secret society to be known as the Jugantar Party, and revitalises the links between the central organisation in Calcutta and its several branches spread all over Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and several places in U.P. Through Justice Sarada Charan Mitra, Jatin leases from Sir Daniel Hamilton lands in the Sundarbans to shelter revolutionaries not yet arrested. Atul Krishna Ghosh & Jatindranath Mukherjee founded PATHURIAGHATA BYAM SAMITY which was an important centre of armed revolution of Indian national movement.They are engaged in night schools for adults, homeopathic dispensaries, workshops to encourage small scale cottage industries, experiments in agriculture. Since 1906, with the help of Sir Daniel, Jatin had been sending meritorious students abroad for higher studies as well as for learning military craft.[22][23]

The Jatin Mukherjee spirit

After the Alipore Case, Jatin organized a series of what author Arun Chandra Guha describes as "daring" actions in Calcutta and in the districts, "to revive the confidence of the people in the movement ... These brought him into the limelight of revolutionary leadership although hardly anybody outside the innermost circle ever suspected his connection with those acts. Secrecy was absolute in those days – particularly with Jatin".[24] Almost contemporaneous with the anarchist gang of Bonnot well known in France, Jatin invented and introduced in India bank robbery on automobile taxi-cabs, " a new feature in revolutionary crime. "[25] Several outrages were committed: for instance, in 1908, on 2 June and 29 November; an attempt to assassinate the Lt Governor of Bengal on 7 November 1908; in 1909, on 27 February 23 April 16 August 24 September and 28 October; two assassinations – of the Prosecutor Ashutosh Biswas (on 10 February 1909) by Charu Chandra Bose, and the Deputy Superintendent of Police, Samsul Alam (on 24 January 1910): both these officers had been determined to get all the accused condemned. Arrested, outwitted by the Police, Biren Datta Gupta, the latter's assassin, disclosed Jatin's name as his leader.

The Howrah-Sibpur conspiracy case

On 25 January 1910, "with the gloom of his assassination hanging over everyone", the Viceroy Minto declared openly: "A spirit hitherto unknown to India has come into existence (...), a spirit of anarchy and lawlessness which seeks to subvert not only British rule but the Governments of Indian chiefs..."[26][27] On 27 January 1910, Jatin was arrested in connection with this murder, but was released, to be immediately re-arrested along with forty-six others in connection with the Howrah-Sibpur conspiracy case, popularly known as the Howrah Gang Case. The major charge against Jatin Mukherjee and his party during the trial (1910–1911) was "conspiracy to wage war against the King-Emperor" and "tampering with the loyalty of the Indian soldiers" (mainly with the 10th Jats Regiment) posted in Fort William, and soldiers in Upper Indian Cantonments.[25] While held in Howrah jail, awaiting trial, Jatin made contact with a few fellow prisoners, prominent revolutionaries belonging to various groups operating in different parts of Bengal, who were all accused in this case. He was also informed by his emissaries abroad that very soon Germany was to declare war against England. Jatin counted heavily on this war to organise an armed uprising along with Indian soldiers in various regiments.[28]

The case failed because of lack of proper evidence thanks to Jatin's policy of a loose decentralised organisation federating scores of regional units, as observed by F.C. Daly more than once: "The gang is a heterogeneous one, with several advisers and petty chiefs... From the information we have on record we may divide the gang into four parts: (1) Gurus, (2) Influential supporters, (3) Leaders, (4) Members."[29] J.C. Nixon's report is more explicit: "Although a separate name and a separate individuality have been given to these various parties in this account of them, and although such a distinction was probably observed amongst the minor members, it is very clear that the bigger figures were in close communication with one another and were frequently accepted members of two or more of these samitis. It may be taken that at some time these various parties were engaged in anarchical crime independently, although in their revolutionary aims and usually in their origins they were all very closely related."[30] Several observers pinpointed Jatin so accurately that the newly appointed Viceroy Lord Hardinge wrote more explicitly to Earl Crewe (H.M.'s Secretary of State for India): "As regards prosecution, I (...) deprecate the net being thrown so wide; as for example in the Howrah Gang Case, where 47 persons are being prosecuted, of whom only one is, I believe, the real criminal. If a concentrated effort had been made to convict this one criminal, I think it would have had a better effect than the prosecution of 46 misguided youths."[31] On 28 May 1911, Hardinge recognized: "The 10th Jats case was part and parcel of the Howrah Gang Case; and with the failure in the latter, the Government of Bengal realised the futility of proceeding with the former... In fact, nothing could be worse, in my opinion, than the condition of Bengal and Eastern Bengal. There is practically no Government in either province..."[32]

A new perspective

Jatin Mukherjee was not involved in the Alipore Bomb case. Jatin was acquitted in February 1911 and released. Immediately, he suspended armed revolution. This stalemate proved Jatin's full command of violence as an antidote, contrary to the Chauri Chaura incident after him. During the German Crown Prince's visit to Calcutta, Jatin met him and received a promise about arms supply.[33] Having lost his government job – and home interned, he managed to leave Calcutta, to start a contract business constructing the Jessore–Jhenaidah railway line. This provided him with a valid pretext and an ample scope to move about on horse-back or on the bicycle to consolidate not only the district units in Bengal, but also to revitalise those in other provinces. Jatin with his family set out on a pilgrimage, and at Haridwar visited his Guru, Bholananda Giri. Jatin went on to Brindavan where he met Swami Niralamba (who had been Jatindra Nath Banerjee, the renowned revolutionary, before leading a sanyasi's life); he had continued preaching in North India Sri Aurobindo's doctrine of a revolution.

Niralamba gave Jatin complementary information about, and links to, the units set up by him in Uttar Pradesh and the Punjab. An important part of revolutionary activities in these regions were led by Rasbehari Bose and his associate Lala Hardayal. On returning from his pilgrimage, Jatin started reorganising Jugantar accordingly. During the Damodar flood in 1913, mainly in the districts of Burdwan and Midnapore, relief work brought together leaders of various groups: Jatin "never asserted his leadership, but the party members in the different districts acclaimed him as their leader."[24]

Meeting with Jatin increased Rasbehari Bose's revolutionary zeal: in Jatin, he discovered "a real leader of men".[34] At the close of 1913, they met to discuss the possibilities of an armed rising of the 1857 type. Impressed by Jatin's "fiery energy and personality", Bose sounded out non-commissioned officers posted at the Fort William of Calcutta, the nerve centre of the various regiments of the colonial army, before returning to Benares "to organise the scattered forces."[35][36]

There were also attempts to organise expatriate Indian revolutionaries in Europe and the United States. Jatin's influence was international. The Bengali bestseller Dhan Gopal Mukerji, settled in New York and, at the summit of his glory, was to write : "Before 1914 we succeeded in disturbing the equilibrium of the government... Then extraordinary powers were given to the police, who called us anarchists to prejudice us forever in the eyes of the world... Dost thou remember Jyotin, our cousin – he that once killed a leopard with a dagger, putting his left elbow in the leopard's mouth and with his right hand thrusting the knife through the brute's eye deep into its brain? He was a very great man and our first leader. He could think of God ten days at a stretch, but he was doomed when the Government found out that he was our head."[37]

Right since 1907, Jatin's emissary, Taraknath Das had been organising, with Guran Ditt Kumar and Surendramohan Bose, evening schools for Indian immigrants (a majority of them Hindus and Sikhs) between Vancouver and San Francisco, through Seattle and Portland: in addition to learning how to read and write simple English, they were informed about their rights in the USA and their duty towards Mother India: two periodicals – Free Hindustan (In English, sponsored by local Irish revolutionaries) and Swadesh Sevak ('Servants of the Motherland', in Gurumukhi) – became increasingly popular. In regular contact with Calcutta and London (where the organisation was managed by Shyamji Krishnavarma), Das wrote regularly to personalities throughout the world (like Leo Tolstoy and Éamon de Valera). In May 1913, Kumar left for Manilla to create a satellite linking Asia with the American West Coast. Familiar with the doctrine of Sri Aurobindo and an erstwhile follower of Rasbehari Bose, in 1913, invited by Das, Har Dayal resigned from his teaching job at the University of Berkeley, coaxed by Jiten Lahiri (one of Jatin's emissaries) of wasting his time in daydreaming, Har Dayal set out on a lecture tour covering the major centres of Indian immigrants; enlivened by their ardent patriotism, he preached open revolt against the English rulers of India. Welcomed by the Indian militants of San Francisco, in November, he founded his journal Ghadar ('Revolt') and the Yugantar Ashram, as a tribute to Sri Aurobindo. The Sikh community also became involved in the movement.

During World War I

Shortly after when World War I broke out, in September 1914, an International Pro-India Committee was formed at Zürich. Very soon it merged into a bigger body, to form the Berlin Committee, or the Indian Independence Committee, led by Virendranath Chattopadhyaya alias Chatto: it gained the support of the German government and had as members prominent Indian revolutionaries abroad, including leaders of the Ghadar Party. Freedom fighters of the Ghadar Party started leaving for India, to join the proposed uprising inside India during World War I, with the help of arms, ammunition, and funds promised by the German government. Advised by Berlin, Ambassador Bernstorff in Washington arranged with Von Papen, his military attaché, to send cargo consignments from California to the coast of the Bay of Bengal, via Far East.[38]

These efforts were directly connected with the Jugantar, under Jatin's leadership, in its planning and organising an armed revolt. Rash Behari Bose assumed the task of carrying out the plan in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab. This international chain work conceived by Jatin came to be known as the German Plot, the Hindu–German Conspiracy, or the Zimmermann Plan. Jugantar started to collect funds by organising a series of dacoities (armed robberies) known as "Taxicab dacoities" and "Boat dacoities". Charles Tegart, in his "Report No. V" on the seditious organisations mentions the "certain amount of success" in the contact that exists between the revolutionaries and the Sikh soldiers posted at Dakshineshwar gunpowder magazine; Jatin Mukherjee in company of Satyendra Sen was seen interviewing these Sikhs. Sen "is the man who came to India with Pingle. Their mission was specially to tamper with the troops. Pingle was captured in Punjab with bombs and was hanged, while Satyen was interned under Regulation III in the Presidency Jail."[39] With Jatin's written instructions, Pingle and Kartar Singh Sarabha met Rasbehari in North India.[40]

Preoccupied by the increasing police activities to prevent any uprising, eminent Jugantar members suggested that Jatin should move to a safer place. Balasore on the Odisha coast was selected as a suitable place, being very near the spot where German arms are to be landed for the Indian rising. To facilitate transmission of information to Jatin, a business house under the name "Universal Emporium" was set up, as a branch of Harry & Sons in Calcutta, which had been created for keeping contacts with revolutionaries abroad. Jatin, therefore, moved to a hideout outside Kaptipada village in the native state of Mayurbhanj, more than thirty miles away from Balasore.

In April 1915, after meeting with Jatin, Naren Bhattacharya (the future M. N. Roy) went to Batavia, to make a deal with the German authorities concerning financial aid and the supply of arms. Through the German consul, Naren met Theodore, brother of Karl Helfferich, who assured him that a cargo of arms and ammunition was already on its way, "to assist the Indians in a revolution".[41]

A network of Czech and Slovak revolutionaries and emigrants had a role in the uncovering of Jatin's plans.[42][43] Its members in the United States, headed by E. V. Voska, were, as Habsburg subjects, presumed to be German supporters, but were actually involved in spying on German and Austrian diplomats. Voska had begun working with Guy Gaunt, who headed Courtenay Bennett's intelligence network, at the outbreak of the war and on learning of the plot from the members of the network in Europe, passed on the information to Gaunt and to Tomáš Masaryk who further passed on the information the Americans.[43][44]

Jatin's death

Jatin was informed of British action by Niren and was requested to leave his hiding place, but his insistence on taking Nirendranath (Niren) Dasgupta and Jyotish Pal with him delayed their departure by a few hours, by which time a large force of police, headed by top British officers from Calcutta and Balasore, reinforced by the army unit from Chandabali in Bhadrak district, had reached the neighborhood. Jatin and his companions walked through the forests and hills of Mayurbhanj, and after two days reached Balasore Railway Station.

The police had announced a reward for the capture of five fleeing "bandits", so the local villagers were also in pursuit. With occasional skirmishes, the revolutionaries, running through jungles and marshy land in torrential rain, finally took up position on 9 September 1915 in an improvised trench in the undergrowth on a hillock at Chashakhand in Balasore. Chittapriya and his companions asked Jatin to leave and go to safety while they guarded the rear. Jatin, however, refused to leave them.

The contingent of Government forces approached them in a pincers movement. A gunfight ensued, lasting seventy-five minutes, between the five revolutionaries armed with Mauser pistols and a large number of police and army armed with modern rifles. The incident known as Battle of Balasore ended with an unrecorded number (25 as per local eye witnesses) of casualties on the Government side. On the other hand, revolutionary Chittapriya Ray Chaudhuri died on spot, Jatin and Jyotish Pal were seriously wounded, and Manoranjan Sengupta and Niren were captured after their ammunition ran out. Jatindranath Mukherjee died at the Balasore district hospital on 10 September 1915. Manoranjan and Niren were hanged at Balasore district jail.

Legacy

Inspired by Swami Vivekananda, Jatin expressed his ideals in simple words: "Amra morbo, jagat jagbe" — "We shall die to awaken the nation".[45] It is corroborated in the tribute paid to Jatin by Charles Tegart, the Intelligence Chief and Police Commissioner of Bengal: "Though I had to do my duty, I have a great admiration for him. He died in an open fight."[46] Later in life, Tegart admitted: "Their driving power (...) immense: if the army could be raised or the arms could reach an Indian port, the British would lose the War". Professor Tripathi analysed the added dimensions revealed by the Howrah Case proceedings: acquire arms locally and abroad; raise a guerrilla; create a rising with Indian soldiers; Jatin Mukherjee's action helped improve (especially economically) the people's status. "He had indeed an ambitious dream."[47]

Informed about his death, M.N. Roy wrote: "I could not forget the injunction of the only man I ever obeyed almost blindly[...] Jatinda's heroic death [...] must be avenged. Only a year had passed since then. But in the meantime, I had come to realise that I admired Jatinda because he personified, perhaps without himself knowing it, the best of mankind. The corollary to that realisation was that Jatinda's death would be avenged if I worked for the ideal of establishing a social order in which the best in man could be manifest."[48]

In 1925, Gandhi told Charles Tegart that Jatin, generally referred to as "Bagha Jatin" (translated as Tiger Jatin), was "a divine personality". Tegart himself is purported to have told his colleagues that if Jatin were an Englishman, then the English people would have built his statue next to Nelson's at Trafalgar Square. In a 1926 note to J.E. Francis of the India Office, he described Bengali revolutionaries as "the most selfless political workers in India".[49]

The locality of Baghajatin in Kolkata has been named after him. Barbati Girls High School situated near the banks of the river Budha Balanga in Balasore town has a statue of Bagha Jatin as it was here the erstwhile Balasore district government hospital was housed and he breathed his last. Chashakhand a place near Phulari just about 15 km east of Balasore has a park in his memorium as it was here he fought the British forces after crossing the Budha Balanga river which flows nearby.

Photo gallery

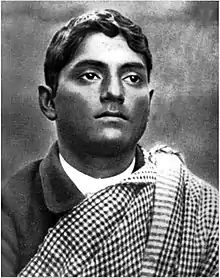

Bagha Jatin in 1895, shortly before joining the University of Calcutta

Bagha Jatin in 1895, shortly before joining the University of Calcutta Bagha Jatin at the age of 24, in Darjeeling, 1903

Bagha Jatin at the age of 24, in Darjeeling, 1903 JATINDRANATH MUKHERJEE IN 1912 : Standing behind Didi Vinodebala (sitting) with his wife Indubala,elder son Tejen (left) and daughter Ashalata (right)

JATINDRANATH MUKHERJEE IN 1912 : Standing behind Didi Vinodebala (sitting) with his wife Indubala,elder son Tejen (left) and daughter Ashalata (right) Bagha Jatin after the final battle. Balasore, 1915

Bagha Jatin after the final battle. Balasore, 1915 Statue of Bagha Jatin near Victoria Memorial, Kolkata

Statue of Bagha Jatin near Victoria Memorial, Kolkata

In popular culture

- In 1958 a patriotic film named Bagha Jatin was released under the direction of Hiranmoy Sen.

- Indian film director Harisadhan Dasgupta made Bagha Jatin, an Indian documentary film on the freedom fighter in 1977. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division.[50]

- In 2023, Bagha Jatin, a film directed by Arun Roy, will be released. Dev is essaying the titular role in the film. Music of the film is being directed by Nilayan Chatterjee.

Notes

- "Remembering Bagha Jatin". The Statesman. 11 September 2013. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Hemant Rout (10 September 2010). "Thousands of visitors and a group of freedom fighters from Orissa and West Bengal on Friday visited Chasakhand, a sleepy village in Orissa's Balasore district that sees a flurry of activity every year on September 10 - the death anniversary of freedom fighter Baghajatin and his four companions. Baghajatin, popularly known as Bengal Tiger, fell to British bullets on Sep 10, 1915, after his four-man army waged a courageous battle at Chasakhand. He continues to be an undying link between West Bengal and Orissa. Born as Jatindranath Mukherjee on December 7, 1889 in Koya village of Kushtia district of undivided Bengal, the revolutionary was known to have fought the British tooth and nail. Chasakhand is perhaps the only memorial place which binds the two states as every year tourists and freedom fighters from West Bengal throng the spot to pay tribute to the revolutionaries". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- SNS (5 September 2018). "Bagha Jatin: The Unsung Hero". The Statesman. Archived from the original on 10 July 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Dictionary of Martyrs India's Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 4. Indian Council of Historical Research. 2016. pp. 178–79.

- Harper, Tim (12 January 2021). Underground Asia: Global Revolutionaries and the Assault on Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72461-7. Archived from the original on 18 September 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Paribarik Katha and Durgotsav, by Lalitkumar Chatterjee, Jatin's uncle and revolutionary colleague, who published also Jatin's biography, Biplabi Jatindranath in 1947.

- Samanta, Vol. II, p. 393.

- Majumdar, Bimanbehari (1966). Militant Nationalism in India. Calcutta: General Printers & Publishers. p. 111. OCLC 8793353.

Mr. Kennedy was ... Editor of the Tirhoot-cowríer [sic]

- Mukherjee, pp. 167–168.

- Dr Kumar Bagchi's Talks with Prithwindra Mukherjee, preserved at the Nehru Museum, New Delhi.

- Samanta, Vol. I, p. 14.

- Samanta, Vol. II, p. 509.

- Samanta, Vol. V, p. 63.

- Notes by Vinodebala Devi.

- Das, M.N. (1964) India under Morley and Minto. George Allen and Unwin. p. 25.

- Political Trouble, p. 9.

- Samanta, Vol. IV, "A Note on the Ramakrishna Mission" by Charles Tegart, pp. 1364–66.

- Report by W. Sealy, "Connections with the Revolutionary organisation in Bihar and Odisha, 1906–16", quoted in Mukherjee, pp. 165–166.

- Notes by Bhavabhûshan. Also, The Statesman, 28 January 1910.

- Mukherjee, p. 166.

- Handwritten Notes by Benodebala Devi, preserved at the Nehru Museum, New Delhi.

- Guha, p. 161: "Workers of the Calcutta Anushilan Samiti started the Bengal Youngmen's Zamindari Co-operative Society ... The idea was to place revolutionary young men in the rural agricultural sector ... Organising small-scale cottage industries and swadeshi stores also engaged the attention of some of these workers."

- Biplabi, pp. 282–283.

- Guha, p.163.

- Rowlatt, Sidney Arthur Taylor (1918) Sedition Committee Report 1918, §68-§69.

- Minto Papers, M.1092, Viceroy's speech at First Meeting of Reformed Council, 25 January 1910

- Das, M.N. (1964) India under Morley and Minto. George Allen and Unwin. p. 122.

- Samanta, Vol. II, "Nixon's Report", p. 591.

- Samanta, Vol. I, p. 60.

- Samanta, Vol. II, p. 522.

- Hardinge Papers, Book 117, No.5, preserved at the Cambridge University Archives.

- Hardinge Papers, Book 81, Vol. II, No.231. (italics added).

- Samanta, Vol. II, "Nixon Report", p. 625.

- Mukherjee, pp. 119.

- Mukherjee, p. 118-119, 177.

- Amarendra Chatterjee's letter dated 4 August 1954 in Biplabi, p.535.

- My Brother's Face, E.P. Dutton & Co, New York, 7th Printing, 1927, pp 206–207. In order not to be taxed of exaggeration, Mukerji seems to have mentioned a "leopard", whereas it was a full grown Royal bengal tiger.

- "England's Indian Trouble" in the Berliner Tageblatt, 6 March 1914.

- Samanta, Vol. III, p. 505

- Majumdar, Bimanbehari (1966). Militant Nationalism in India. Calcutta: General Printers & Publishers. p. 167. OCLC 8793353.

[Satyen Sen] had as his fellow-travellers in the ship men like Vishnu Ganesh Pingle of Maharashtra and Kartar Singh of the Punjab. He introduced them to Jatin Miukherjee who sent them to Rash Behari Basu.

- Mukherjee, p. 186.

- Voska, Emanuel Victor; Irwin, Will (1940), Spy and Counterspy, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co, p. 141

- Masaryk, T. (1970), Making of a State, Howard Fertig, p. 242, ISBN 0-685-09575-4

- Popplewell, Richard J. (1995), Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire 1904–1924, Routledge, p. 237, ISBN 0-7146-4580-X

- Datta, Bhupendrakumar (1953). Biplaber padachinha. 2nd ed., p. 74.

- Samanta, Vol. III, Introduction, p. viii

- Tripathi, Amales (1991) Swadhinata Samgram'e Bharater Jatiya Congress (1885–1947). 2nd Edition. Ananda Publishers. pp. 77–78.

- Roy, pp. 35–36.

- The Statesman, Calcutta, 28 April 2009

- "BAGHA JATIN". filmsdivision.org. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

Cited sources

- Mukhopadhyay, Jadugopal (1982). Biplabi jîbaner smriti.

- Guha, Arun Chandra (1971). First spark of revolution: the early phase of India's struggle for independence, 1900–1920. Orient Longman. ISBN 9780883860380.

- Mukherjee, Uma (1966). Two Great Indian Revolutionaries (1st ed.). Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

- Roy, M. N. (1964) [First published 1960]. M.N. Roy's Memoirs. Allied Publisher.

- Samanta, A.K., ed. (1995). Terrorism in Bengal. Government of West Bengal, Calcutta.

Further reading

- Bhupendrakumar Datta, "Mukherjee, Jatindranath (1879–1915)" in Dictionary of National Biography volume III, ed. S.P. Sen (Calcutta: Institute of Historical Studies, 1974), pp 162–165.

- Saga of Patriotism article on Bagha Jatin by Sadhu Prof. V. Rangarajan and R. Vivekanandan.

- W. Sealy, Connections with the Revolutionary Organisation in Bihar and Orissa, 1906–1916.

- Report classified as Home Polit-Proceedings A, March 1910, nos 33–40 (cf Sumit Sarkar, The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal, 1903–1908, New Delhi, 1977, p. 376

- Sisirkumar Mitra, Resurgent India, Allied Publishers, 1963, p. 367.

- J.C. Ker, ICS, Political Trouble in India, a Confidential Report, Delhi, 1973 (repr.), p. 120. Also (i) "Taraknath Das" by William A. Ellis, 1819–1911, Montpellier, 1911, Vol. III, pp490–491, illustrated (with two of Tarak’s photos); (ii) "The Vermont Education of Taraknath Das : an Episode in British-American-Indian Relations", Ronald Spector, in Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, Vol. 48, No 2, 1980, pp 88–95; (iii) Les origines intellectuelles du mouvement d'indépendance de l'Inde (1893–1918), by Prithwindra Mukherjee, PhD Thesis, University of Paris, 1986.

- German Foreign Office Documents, 1914–18 (Microfilms in National Archives of India, New Delhi). Also, San Francisco Trial Report, 75 Volumes (India Office Library, UK) and Record Groups 49, 60, 85, and 118 (US National Archives, Washington DC, and Federal Archives, San Bruno).

- Amales Tripathi, svâdhînatâ samgrâmé bhâratér jâtiya congress (1885–1947), Ananda Publishers Pr. Ltd, Kolkâtâ, 1991, 2nd edition, pp 77–79.

- Bagha Jatin by Prithwindra Mukherjee in Challenge : A Saga of India’s Struggle for Freedom, ed. Nisith Ranjan Ray et al., New Delhi, 1984, pp 264–273.

- Sedition Committee Report, 1918.

- Bagha Jatin by Prithwindra Mukherjee, Dey’s Publishing, Calcutta, 2003 (4th Edition), 128p [in Bengali].

- Bagha Jatin: Life and Times of Jatindranath Mukherjee by Prithwindra Mukherjee, National Book Trust, New Delhi, 2010, First revised edition 2013, launched by H.E. Pranab Mukherjee

- Bagha Jatin, the Revolutionary Legacy, by Prithwindra Mukherjee, Indus Source Books, Mumbai, 2015

- The Intellectual Roots of India's Freedom Struggle (1893–1918), by Prithwindra Mukherjee, Manohar, New Delhi, 2017

- Samasamayiker chokhe Baghajatin, edited by Prithwindra Mukherjee and Pabitrakumar Gupta, Sahitya Samsad, Kolkata, 2014 ["Bagha Jatin in the Eyes of his Contemporaries"]

- Sâdhak biplabi jatîndranâth , by Prithwindra Mukherjee, West Bengal Books Board, kolkata, 1991

See also

External links

- Jatindranath Mukherjee – Bhupendrakumar Datta.

- Great Indians.