Celali rebellions

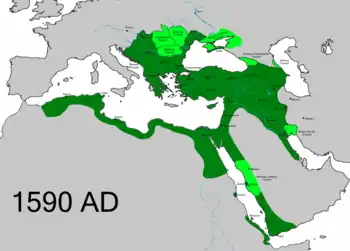

The Celali rebellions (Turkish: Celalî ayaklanmaları) were a series of rebellions in Anatolia of irregular troops led by bandit chiefs and provincial officials known as celalî, celâli, or jelālī,[1] against the authority of the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th and early to mid-17th centuries. The first revolt termed as such occurred in 1519, during Sultan Selim I's reign, near Tokat under the leadership of Celâl, an Alevi preacher. Celâl's name was later used by Ottoman histories as a general term for rebellious groups in Anatolia, most of whom bore no particular connection to the original Celâl.[2] As it is used by historians, the "Celali Rebellions" refer primarily to the activity of bandits and warlords in Anatolia from c. 1590 to 1610, with a second wave of Celali activity, this time led by rebellious provincial governors rather than bandit chiefs, lasting from 1622 to the suppression of the revolt of Abaza Hasan Pasha in 1659. These rebellions were the largest and longest lasting in the history of the Ottoman Empire.

The major uprisings involved the sekbans (irregular troops of musketeers) and sipahis (cavalrymen maintained by land grants). The rebellions were not attempts to overthrow the Ottoman government but were reactions to a social and economic crisis stemming from a number of factors: demographic pressure following a period of unprecedented population growth during the 16th century, climatic hardship associated with the Little Ice Age, a depreciation of the currency, and the mobilization of thousands of sekban musketeers for the Ottoman army during its wars with the Habsburgs and Safavids, who turned to banditry when demobilized. Celali leaders often sought no more than to be appointed to provincial governorships within the empire, while others fought for specific political causes.[3] Such as Abaza Mehmed Pasha's effort to topple the Janissary government established after the regicide of Osman II in 1622, or Abaza Hasan Pasha's desire to overthrow the grand vizier Köprülü Mehmed Pasha. The Ottoman leaders understood why the Celali rebels were making demands, so they gave some of the Celali leaders government jobs to stop the rebellion and make them part of the system. The Ottoman army used force to defeat those who didn't get jobs and kept fighting. The Celali rebellion ended when the most powerful leaders became part of the Ottoman system and the weaker ones were defeated by the Ottoman army. The Janissaries and former rebels who had joined the Ottomans fought to keep their new government jobs.[3]

Major revolts

Karayazıcı (1598)

Especially after the 1550s, with the increase of oppression by local governors and levying of new and high taxes, minor incidents started to occur with increasing frequency. After the beginning of the wars with Persia, especially after 1584, Janissaries began seizing the lands of the farmworkers to extort money, and also lent money with high interest rates, thus causing the tax revenues of the state to drop seriously.

In 1598 a sekban leader, Karayazıcı Abdülhalim, united the dissatisfied groups in the Anatolia Eyalet and established a base of power in Sivas and Dulkadir, where he was able to force towns to pay tribute to him.[1] He was offered the governorship of Çorum, but refused the post and when Ottoman forces were sent against them, he retreated with his forces to Urfa, seeking refuge in a fortified castle, which became the center of resistance for 18 months. Out of fear that his forces would mutiny against him, he left the castle, was defeated by government forces, and died some time later in 1602 from natural causes. His brother Deli Hasan then seized Kutahya, in western Anatolia, but later he and his followers were won over by grants of governorships.[1]

Later

The Celali unrests, however, continued under the leadership of Janbuladoglu in Aleppo and Yusuf Pasha and Kalenderoğlu in western Anatolia. They were finally suppressed by the grand vizier Kuyucu Murad Pasha, who by 1610 had eliminated a large number of Jelalis.

See also

References

- "Jelālī Revolts | Turkish history". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2012-10-25.

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (2010-05-21). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438110257.

- Anderson, Betty S. (2016). A history of the modern Middle East : rulers, rebels, and rogues. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8047-9875-4. OCLC 945376555.

Further reading

- Barkey, Karen. Bandits and Bureaucrats: The Ottoman Route to State Centralization. Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Griswold, William J. The Great Anatolian Rebellion, 1000-1020/1591-1611 (Islamkundliche Untersuchungen), 1983. K. Schwarz Verlag. ISBN 3-922968-34-1.

- İnalcık, Halil. “Military and Fiscal Transformation in the Ottoman Empire, 1600-1700.” Archivum Ottomanicum 6 (1980): 283–337.

- Özel, Oktay. “The Reign of Violence: The Celalis c. 1550-1700.” In The Ottoman World, 184–202. Edited by Christine Woodhead. London: Routledge, 2011.

- White, Sam. The Climate of Rebellion in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.