Old City of Jerusalem

The Old City of Jerusalem is a 0.9-square-kilometre (0.35 sq mi) walled area[2] in East Jerusalem.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top:

| |

| Location | East Jerusalem |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 148 |

| Inscription | 1981 (5th Session) |

| Endangered | 1982–present |

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

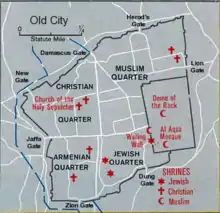

The Old City is today divided into four uneven quarters, in a tradition which may have begun with an 1840s British map of the city;[3] these are the Muslim Quarter, the Christian Quarter, the Armenian Quarter, and the Jewish Quarter.[4] A fifth area, the Temple Mount, known to Muslims as Al-Aqsa or Haram al-Sharif, is home to the Dome of the Rock, the Al-Aqsa Mosque and was once the site of the Jewish Temple. The Old City's current walls and city gates were built by the Ottoman Empire from 1535 to 1542 under Suleiman the Magnificent. The Old City is home to several sites of key importance and holiness to the three major Abrahamic religions: the Temple Mount and the Western Wall for Judaism, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for Christianity, and the Dome of the Rock and al-Aqsa Mosque for Islam. The Old City, along with its walls, was added to the World Heritage Site list of UNESCO in 1981.

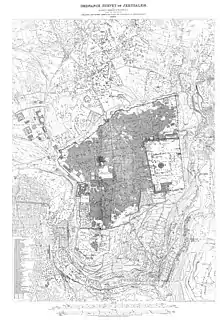

In spite of its name, the Old City of Jerusalem's current layout is different from that of ancient times. Most archeologists believe that the City of David, an archaeological site on a rocky spur south of the Temple Mount, was the original settlement core of Jerusalem during the Bronze and Iron Ages.[5][6][7][8][9] At times, the ancient city spread to the east and north, covering Mount Zion and the Temple Mount. The Old City as defined by the walls of Suleiman is thus shifted a bit northwards compared to earlier periods of the city's history, and smaller than it had been in its peak, during the late Second Temple period. The Old City's current layout has been documented in significant detail, notably in old maps of Jerusalem over the last 1,500 years.

Until the mid-19th century, the entire city of Jerusalem (with the exception of David's Tomb complex) was enclosed within the Old City walls. The departure from the walls began in the 19th century, when the city's municipal borders were expanded to include Arab villages such as Silwan and new Jewish neighborhoods such as Mishkenot Sha'ananim. The Old City came under Jordanian control following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. During the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel occupied East Jerusalem; since then, the entire city has been under Israeli control. Israel unilaterally asserted in its 1980 Jerusalem Law that the whole of Jerusalem was Israel's capital.[10] In international law East Jerusalem is defined as territory occupied by Israel.

Population

In 1967, the Old City contained 17,000 Muslims, 6,000 Christians (including Armenians) and no Jews, as the latter had been expelled from the city in the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[11]

The current population of the Old City resides mostly in the Muslim and Christian quarters. In 2007, the total population was 36,965; there were 27,500 Muslims (growing to over 30,000 by 2013); 5,681 non-Armenian Christians, 790 Armenians (who decreased in number to about 500 by 2013); and 3,089 Jews (with almost 3,000 plus some 1,500 yeshiva students by 2013).[12][11][13]

Political status

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Old City was captured by Jordan and all its Jewish residents were evicted. During the Six-Day War in 1967, which saw hand-to-hand fighting on the Temple Mount, Israeli forces captured the Old City along with the rest of East Jerusalem, subsequently annexing them as Israeli territory and reuniting them with the western part of the city. Today, the Israeli government controls the entire area, which it considers part of its national capital. However, the Jerusalem Law of 1980, which effectively annexed East Jerusalem to Israel, was declared null and void by United Nations Security Council Resolution 478. East Jerusalem is now regarded by the international community as part of occupied Palestinian territory.[14][15]

History

Israelite period

According to the Hebrew Bible, before King David's conquest of Jerusalem in the 11th century BCE the city was home to the Jebusites. The Bible describes the city as heavily fortified with a strong city wall, a fact confirmed by archaeology. The Bible names the city ruled by King David as the City of David, in Hebrew Ir David, which was identified southeast of the Old City walls, outside the Dung Gate. In the Bible, David's son, King Solomon, extended the city walls to include the Temple and Temple Mount. After the partition of the United Kingdom of Israel, the southern tribes remained in Jerusalem, with the city becoming the capital of the Kingdom of Judah.[16]

Jerusalem was largely extended westwards after the Neo-Assyrian destruction of the northern Kingdom of Israel and the resulting influx of refugees. King Hezekiah had been preparing for an Assyrian invasion by fortifying the walls of the capital, building towers, and constructing a tunnel to bring fresh water to the city from a spring outside its walls.[17] He made at least two major preparations that would help Jerusalem to resist conquest: the construction of the Siloam Tunnel, and construction of the Broad Wall. The First Temple period ended around 586 BCE, as Nebuchadnezzar's Neo-Babylonian Empire conquered Judah and Jerusalem, and laid waste to Solomon's Temple and the city.[18]

Second Temple period

In 538 BCE, the Persian King Cyrus the Great invited the Jews of Babylon to return to Judah to rebuild the Temple.[19] Construction of the Second Temple was completed in 516 BCE, during the reign of Darius the Great, 70 years after the destruction of the First Temple.[20][21] The city was rebuilt on a smaller scale in about 440 BCE, during the Persian period, when, according to the Bible, Nehemiah led the Jews who returned from the Babylonian Exile. An additional, so-called Second Wall, was built by King Herod the Great, who also expanded the Temple Mount and rebuilt the Temple. In 41–44 CE, Agrippa, king of Judea, started building the so-called "Third Wall" around the northern suburbs. The entire city was totally destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE.[22]

Late Roman, Byzantine, and Early Muslim periods

The northern part of the city was rebuilt by the Emperor Hadrian around 130, under the name Aelia Capitolina. In the Byzantine period Jerusalem was extended southwards and again enclosed by city walls.

Muslims occupied Byzantine Jerusalem in the 7th century (637 CE) under the second caliph, `Umar Ibn al-Khattab who annexed it to the Islamic Arab Empire. He granted its inhabitants an assurance treaty. After the siege of Jerusalem, Sophronius welcomed `Umar, allegedly because, according to biblical prophecies known to the Church in Jerusalem, "a poor, but just and powerful man" would rise to be a protector and ally to the Christians of Jerusalem. Sophronius believed that `Umar, a great warrior who led an austere life, was a fulfillment of this prophecy. In the account by the Patriarch of Alexandria, Eutychius, it is said that `Umar paid a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and sat in its courtyard. When the time for prayer arrived, however, he left the church and prayed outside the compound, in order to avoid having future generations of Muslims use his prayer there as a pretext for converting the church into a mosque. Eutychius adds that `Umar also wrote a decree which he handed to the Patriarch, in which he prohibited Muslims gathering in prayer at the site.[23]

Crusader & Ayyubid periods

In 1099, Jerusalem was captured by the Western Christian army of the First Crusade and it remained in their hands until recaptured by the Arab Muslims, led by Saladin, on October 2, 1187. He summoned the Jews and permitted them to resettle in the city. In 1219, the walls of the city were razed by Sultan Al-Mu'azzam of Damascus; in 1229, by treaty with Egypt, Jerusalem came into the hands of Frederick II of Germany. In 1239 he began to rebuild the walls, but they were demolished again by Da'ud, the emir of Kerak. In 1243, Jerusalem came again under the control of the Christians, and the walls were repaired. The Khwarazmian Turks took the city in 1244 and Sultan Malik al-Muazzam razed the walls, rendering it again defenseless and dealing a heavy blow to the city's status.

Ottoman period

The current walls of the Old City were built in 1535–42 by the Ottoman Turkish sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The walls stretch for approximately 4.5 km (2.8 miles), and rise to a height of between 5 and 15 metres (16.4–49 ft), with a thickness of 3 metres (10 feet) at the base of the wall.[4] Altogether, the Old City walls contain 35 towers, of which 15 are concentrated in the more exposed northern wall.[4] Suleiman's wall had six gates, to which a seventh, the New Gate, was added in 1887; several other, older gates, have been walled up over the centuries. The Golden Gate was at first rebuilt and left open by Suleiman's architects, only to be walled up a short while later. The New Gate was opened in the wall surrounding the Christian Quarter during the 19th century. Two secondary gates were reopened in recent times on the southeastern side of the city walls as a result of archaeological work.

UNESCO status

In 1980, Jordan proposed that the Old City be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[25] It was added to the List in 1981.[26] In 1982, Jordan requested that it be added to the List of World Heritage in Danger. The United States government opposed the request, noting that the Jordanian government had no standing to make such a nomination and that the consent of the Israeli government would be required since it effectively controlled Jerusalem.[27] In 2011, UNESCO issued a statement reiterating its view that East Jerusalem is "part of the occupied Palestinian territory, and that the status of Jerusalem must be resolved in permanent status negotiations."[28]

Archaeology

Israelite period

Among the Israelite period finds in the Old City are two portions of the 8th and 7th century BCE city walls, in the area of the Israelite Tower, probably including parts of a gate where numerous projectiles were found, attesting to the Babylonian sack of Jerusalem in 586 BCE.[29][30][31] Another part of the late 8th-century BCE fortification discovered was dubbed the "broad wall", after the way it was described in the Book of Nehemiah, built to defend Jerusalem against the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem of 701 BCE.[30][29][32]

Hellenistic period

In 2015, archaeologists uncovered the remnants of an impressive fort, built by Greeks in the center of old Jerusalem. It is believed that it is the remnants of the Acra fortress. The team also found coins that date from the time of Antiochus IV to the time of Antiochus VII. In addition, they found Greek arrowheads, slingshots, ballistic stones and amphorae.[33]

In 2018, archaeologists discovered a 4-centimeter-long filigree gold earring with a ram's head around 200 meters south of the Temple Mount. The Israel Antiquities Authority said it was consistent with jewelry from the early Hellenistic period (3rd or early 2nd century BCE). Adding that it was the first time somebody finds a golden earring from the Hellenistic times in Jerusalem.[34]

Herodian period

Many structures dated to the Herodian period were discovered in the Jewish Quarter during archaeological excavations carried out between 1967 and 1983. Among them was unearthed a palatial mansion from the Herodian period,[35] believed to be the residence of Annas the High Priest.[36] In its vicinity, a depiction of the Temple menorah was discovered, carved while its model still stood in the Temple, engraved in a plastered wall.[36] The palace has been destroyed during the final days of the Roman siege of 70 CE, suffering the same fate as the so-called Burnt House, a building belonging to the Kathros priestly family, which was found nearby.[37][30]

In 1968, the Trumpeting Place inscription was found at the southwest corner of Temple Mount, and is believed to mark the site where the priests used to declare the advent of Shabbat and other Jewish holidays.[38]

Byzantine period

In the 1970s, while excavating the remains of the Nea Church (the New Church of the Theotokos), a Greek inscription was found. It reads: "This work too was donated by our most pious Emperor Flavius Justinian, through the provision and care of Constantine, most saintly priest and abbot, in the 13th year of the indiction."[39][40] A second dedicatory inscription bearing the names of Emperor Justinian and of the same abbot of the Nea Church was discovered in 2017 among the ruins of a pilgrim hostel about a kilometre north of Damascus Gate, which proves the importance of the Nea complex at the time.[40][41]

Quarters

The Old City is today divided into four uneven quarters: the Muslim Quarter, the Christian Quarter, the Armenian Quarter and the Jewish Quarter. Matthew Teller writes that this four-quarter convention may have originated in the 1841 British Royal Engineers map of Jerusalem,[3] or at least Reverend George Williams' subsequent labelling of it.[42]

This 19th-century cartographic partition into four quarters represented the historical development of the city that had previously been divided into many more harat (Arabic: حارَة, romanized: Hārat: "quarters", "neighborhoods", "districts" or "areas", see wikt:حارة);[43] the Christian and Jewish areas of the city had grown considerably over the preceding centuries.[44][45][46]

Despite the names, there was no governing principle of ethnic segregation: 30 percent of the houses in the Muslim quarter were rented out to Jews, and 70 percent of the Armenian quarter.[47]

Below is a table of the historically recorded quarters of the city, from 1495 up until the modern system:[48]

| Local divisions | Western divisions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 1495 | 1500s | 1800s | 1900 | 1840s onwards | |

| Source | Mujir al-Din | Ottoman census | Traditional system | Ottoman census | Modern maps | |

| Quarters | Ghuriyya (Turiyya) | Bab el-Asbat | Muslim Quarter (north) | North-east | ||

| Bab Hutta | Bab Hutta | Bab Hutta | Bab Hutta | |||

| Masharqa | ||||||

| Bani Zayd | Bani Zayd | Sa'diyya | Sa'diyya | North-west | ||

| Bab el-'Amud | Bab el-'Amud | Bab el-'Amud | Bab el-'Amud | |||

| Bani Murra | ||||||

| Zara'na | Dara'na | Haddadin | Nasara | Christian Quarter | North | |

| Khan ez-Zeyt | East | |||||

| Nasara ("Christian") | Nasara | Middle and south | ||||

| Mawarna | ||||||

| Jawalda | Jawalda | West | ||||

| Bani Harith | Bani Harith | Jawa'na | Sharaf | Armenian Quarter | West | |

| Dawiyya | North | |||||

| Arman ("Armenian") | Sihyun | Arman | South | |||

| Yahud ("Jewish") | Yahud | East | ||||

| Risha | Silsila | Jewish Quarter | South | |||

| Maslakh | ||||||

| Saltin | Khawaldi | |||||

| Sharaf | Sharaf (Alam) | |||||

| 'Alam | North | |||||

| Magharba ("Moroccan / Maghrebi") | Magharba | Magharba | East | |||

| Marzaban | Bab el-Qattanin | Bab es-Silsila | Wad | Muslim Quarter (south) | South | |

| Qattanin | ||||||

| Aqabet es-Sitta | Wad | |||||

| 'Aqabet et-Takiya | ||||||

| (Outside the city walls) | Nebi Daud | Mount Zion | ||||

Muslim Quarter

The Muslim Quarter (Arabic: حارَة المُسلِمين, Hārat al-Muslimīn) is the largest and most populous of the four quarters and is situated in the northeastern corner of the Old City, extending from the Lions' Gate in the east, along the northern wall of the Temple Mount in the south, to the Western Wall – Damascus Gate route in the west. During the British Mandate, Sir Ronald Storrs embarked on a project to rehabilitate the Cotton Market, which was badly neglected under the Turks. He describes it as a public latrine with piles of debris up to five feet high. With the help of the Pro-Jerusalem Society, vaults, roofing and walls were restored, and looms were brought in to provide employment.[49]

Like the other three quarters of the Old City, until the riots of 1929 the Muslim quarter had a mixed population of Muslims, Christians, and also Jews.[50] Today, there are "many Israeli settler homes" and "several yeshivas", including Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim, in the Muslim Quarter.[12] Its population was 22,000 in 2005.

Christian Quarter

The Christian Quarter (Arabic: حارة النصارى, Ḩārat an-Naşāra) is situated in the northwestern corner of the Old City, extending from the New Gate in the north, along the western wall of the Old City as far as the Jaffa Gate, along the Jaffa Gate – Western Wall route in the south, bordering the Jewish and Armenian Quarters, as far as the Damascus Gate in the east, where it borders the Muslim Quarter. The quarter contains the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, viewed by many as Christianity's holiest place.

Armenian Quarter

The Armenian Quarter (Armenian: Հայկական Թաղամաս, Haygagan T'aġamas, Arabic: حارة الأرمن, Ḩārat al-Arman) is the smallest of the four quarters of the Old City. Although the Armenians are Christian, the Armenian Quarter is distinct from the Christian Quarter. Despite the small size and population of this quarter, the Armenians and their Patriarchate remain staunchly independent and form a vigorous presence in the Old City. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the four quarters of the city came under Jordanian control. Jordanian law required Armenians and other Christians to "give equal time to the Bible and Qur'an" in private Christian schools, and restricted the expansion of church assets. The 1967 war is remembered by residents of the quarter as a miracle, after two unexploded bombs were found inside the Armenian monastery. Today, more than 3,000 Armenians live in Jerusalem, 500 of them in the Armenian Quarter.[51][52] Some are temporary residents studying at the seminary or working as church functionaries. The Patriarchate owns the land in this quarter as well as valuable property in West Jerusalem and elsewhere. In 1975, a theological seminary was established in the Armenian Quarter. After the 1967 war, the Israeli government gave compensation for repairing any churches or holy sites damaged in the fighting, regardless of who caused the damage.

Jewish Quarter

.jpg.webp)

The Jewish Quarter (Hebrew: הרובע היהודי, HaRova HaYehudi, known colloquially to residents as HaRova, Arabic: حارة اليهود, Ḩārat al-Yahūd) lies in the southeastern sector of the walled city, and stretches from the Zion Gate in the south, bordering the Armenian Quarter on the west, along the Cardo to Chain Street in the north and extends east to the Western Wall and the Temple Mount. The quarter has a rich history, with several long periods of Jewish presence covering much of the time since the eighth century BCE.[53][54][55][56][57] In 1948, its population of about 2,000 Jews was besieged, and forced to leave en masse.[58] The quarter was completely sacked by Arab forces during the Battle for Jerusalem and ancient synagogues were destroyed.

The Jewish quarter remained under Jordanian control until its recapture by Israeli paratroopers in the Six-Day War of 1967. A few days later, Israeli authorities ordered the demolition of the adjacent Moroccan Quarter, forcibly relocating all of its inhabitants, in order to facilitate public access to the Western Wall. 195 properties – synagogues, yeshivas, and apartments – were registered as Jewish and fell under the control of Jordan's Custodian of Enemy Property. Most were occupied by Palestinian refugees expelled by Israeli forces from West Jerusalem and its contiguous villages until UNWRA and Jordan constructed the Shuafat Refugee Camp, where many were shifted, leaving most of the properties empty of inhabitants.[59]

In 1968, after the Six Day War, Israel confiscated 12%, including the Jewish quarter and contiguous areas, of the Old City for public use. Some 80% of this confiscated infrastructure consisted of properties not owned by Jews.[59] After reconstruction the parts of the quarter destroyed prior to 1967, these properties were then offered for sale exclusively to the Israeli and Jewish public. The prior owners mostly refused because their properties were part of Islamic family waqfs, which cannot be put up for sale.[59] As of 2005, the population stood at 2,348.[60] Many large educational institutions have taken up residence. Before being rebuilt, the quarter was carefully excavated under the supervision of Hebrew University archaeologist Nahman Avigad. The archaeological remains are on display in a series of museums and outdoor parks, which tourists can visit by descending two or three stories beneath the level of the current city. The former Chief Rabbi is Avigdor Nebenzahl, and the current Chief Rabbi is his son Chizkiyahu Nebenzahl, who is on the faculty of Yeshivat Netiv Aryeh, a school situated directly across from the Western Wall.

The quarter includes the "Karaites' street" (Hebrew: רחוב הקראים, Rehov Ha'Karaim), on which the old Anan ben David Kenesa is located.[61]

Moroccan Quarter

There was previously a small Moroccan quarter in the Old City. Within a week of the Six-Day War's end, the Moroccan quarter was largely destroyed in order to give visitors better access to the Western Wall by creating the Western Wall Plaza. The parts of the Moroccan Quarter that were not destroyed are now part of the Jewish Quarter. Simultaneously with the demolition, a new regulation was set into place by which the only access point for non-Muslims to the Temple Mount is through the Gate of the Moors, which is reached via the so-called Mughrabi Bridge.[62][63]

Gates

During different periods, the city walls followed different outlines and had a varying number of gates. During the era of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem for instance, Jerusalem had four gates, one on each side. The current walls were built by Suleiman the Magnificent, who provided them with six gates; several older gates, which had been walled up before the arrival of the Ottomans, were left as they were. As to the previously sealed Golden Gate, Suleiman at first opened and rebuilt it, but then walled it up again as well. The number of operational gates was brought back to seven after the addition of the New Gate in 1887; a smaller one, popularly known as the Tanners' Gate, has been opened for visitors after being discovered and unsealed during excavations in the 1990s. The sealed historic gates comprise four that are at least partially preserved (the double Golden Gate in the eastern wall, and the Single, Triple, and Double Gates in the southern wall), with several other gates discovered by archaeologists of which only traces remain (the Gate of the Essenes on Mount Zion, the gate of Herod's royal palace south of the citadel, and the vague remains of what 19th-century explorers identified as the Gate of the Funerals (Bab al-Jana'iz) or of al-Buraq (Bab al-Buraq) south of the Golden Gate[64]).

Until 1887, each gate was closed before sunset and opened at sunrise. These gates have been known by a variety of names used in different historical periods and by different communities.

Gallery

Street bazaar (souq), Christian Quarter Road (2006)

Street bazaar (souq), Christian Quarter Road (2006) Entrance to the citadel, popularly known as the Tower of David

Entrance to the citadel, popularly known as the Tower of David

See also

Bibliography

- Arnon, Adar (1992). "The Quarters of Jerusalem in the Ottoman Period". Middle Eastern Studies. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 28 (1): 1–65. doi:10.1080/00263209208700889. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4283477. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

References

- "Old City of Jerusalem and its Walls". UNESCO. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Kollek, Teddy (1977). "Afterword". In John Phillips (ed.). A Will to Survive – Israel: the Faces of the Terror 1948-the Faces of Hope Today. Dial Press/James Wade.

about 225 acres

- Teller, Matthew (2022). Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City. Profile Books. p. Chapter 1. ISBN 978-1-78283-904-0. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

What wasn't corrected, though – and what, in retrospect, should have raised much more controversy than it did (it seems to have passed completely unremarked for the last 170-odd years) – was [Aldrich and Symonds's] map's labelling. Because here, newly arcing across the familiar quadrilateral of Jerusalem, are four double labels in bold capitals. At top left Haret En-Nassara and, beneath it, Christian Quarter; at bottom left Haret El-Arman and Armenian Quarter; at bottom centre Haret El-Yehud and Jews' Quarter; and at top right – the big innovation, covering perhaps half the city – Haret El-Muslimin and Mohammedan Quarter. had shown this before. Every map has shown it since. The idea, in 1841, of a Mohammedan (that is, Muslim) quarter of Jerusalem is bizarre. It's like a Catholic quarter of Rome. A Hindu quarter of Delhi. Nobody living there would conceive of the city in such a way. At that time, and for centuries before and decades after, Jerusalem was, if the term means anything at all, a Muslim city. Many people identified in other ways, but large numbers of Jerusalemites were Muslim and they lived all over the city. A Muslim quarter could only have been dreamt up by outsiders, searching for a handle on a place they barely understood, intent on asserting their own legitimacy among a hostile population, seeing what they wanted to see. Its only purpose could be to draw attention to what it excludes.

- Eliyahu Wager (1988). Illustrated guide to Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Publishing House. p. 138.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (March 6, 2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743223386 – via Google Books.

- Ariel, D. T., & De Groot, A. (1978). "The Iron Age extramural occupation at the City of David and additional observations on the Siloam Channel." Excavation at the City of David, 1985.

- Broshi (1974), pp. 21–26.

- Reich, R., & Shukron, E. (2000). "The Excavations at the Gihon Spring and Warren's Shaft System in the City of David." Ancient Jerusalem Revealed. Jerusalem, 327–339.

- Geva, Hillel; De Groot, Alon (2017). "The City of David Is Not on the Temple Mount After All". Israel Exploration Journal. 67 (1): 32–49. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 44474016.

The prevailing view among researchers that the early city, the City of David, lay in the southern part of the eastern ridge next to the spring.

- "Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 30 July 1980. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- Bracha Slae (13 July 2013). "Demography in Jerusalem's Old City". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Jerusalem The Old City: Urban Fabric and Geopolitical Implications" (PDF). International Peace and Cooperation Center. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-28.

- Beltran, Gray (9 May 2011). "Torn between two worlds and an uncertain future". Columbia Journalism School. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- East Jerusalem: Key Humanitarian Concerns Archived 2013-07-21 at the Wayback Machine United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory. December 2012

- Benveniśtî, Eyāl (2004). The international law of occupation. Princeton University Press. pp. 112–13. ISBN 978-0-691-12130-7.

- Richard A. Freund, Digging Through the Bible: Modern Archaeology and the Ancient Bible, p. 9, at Google Books, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009, p. 9.

- "Sennacherib and Jerusalem".

- Zank, Michael. "Capital of Judah I (930–722)". Boston University. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- "Ezra 1:1–4; 6:1–5". Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- Sicker, Martin (2001). Between Rome and Jerusalem: 300 Years of Roman-Judaean Relations. Praeger Publishers. p. 2. ISBN 0-275-97140-6.

- Zank, Michael. "Center of the Persian Satrapy of Judah (539–323)". Boston University. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- Zissu, Boaz (2018). "Interbellum Judea 70-132 CE: An Archaeological Perspective". Jews and Christians in the First and Second Centuries: The Interbellum 70‒132 CE. Joshua Schwartz, Peter J. Tomson. Leiden, The Netherlands. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-04-34986-5. OCLC 988856967.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "The Holy Sepulchre – first destructions and reconstructions". Christusrex.org. 2001-12-26. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- Annual Report, 1936, of the Department of Land and Surveys, page 368: "In 1936 a complete map of the Old City of Jerusalem was published on the scale 1/2,500. The only previous map of the Old City was that made in 1865 by Sir Charles Wilson, previously mentioned. This map is apparently often called by writers the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem! Anyhow, it proved itself worthy of the title, for Lieut-Col F. J. Salmon states that it was sufficiently accurate to be used as the framing of the new map. The old map showed no more than the streets and principal edifices; the new shows all the structures"

- Advisory Body Evaluation (PDF file)

- "Report of the 1st Extraordinary Session of the World Heritage Committee". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- "Justification for inscription on the List of World Heritage in Danger, 1982: Report of the 6th Session of the World Heritage Committee". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- "UNESCO replies to allegations". UNESCO. 15 July 2011.

The Old City of Jerusalem is inscribed on the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger. UNESCO continues to work to ensure respect for the outstanding universal value of the cultural heritage of the Old City of Jerusalem. This position is reflected on UNESCO's official website (www.unesco.org). In line with relevant UN resolutions, East Jerusalem remains part of the occupied Palestinian territory, and the status of Jerusalem must be resolved in permanent status negotiations.

- Geva, Hillel (2003). "Western Jerusalem at the end of the First Temple Period in Light of the Excavations in the Jewish Quarter". In Vaughn, Andrew G; Killebrew, Ann E (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and archaeology: the First Temple period. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 183–208. ISBN 978-1-58983-066-0.

- Geva, Hillel (2010). Jewish Quarter Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem. Volume IV: The Burnt House of Area B and Other Studies (Abstract). Israel Exploration Society. Retrieved 9 September 2020 – via Harvard University website, the Shelby White and Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications.

- Murphy-O'Connor (2008), pp. 76–78

- Murphy-O'Connor (2008), p. 76, Fig. 1/3 (p.10)

- "Jerusalem Dig Uncovers Ancient Greek Citadel".

- "In find of ancient gold earring, echoes of Greek rule over Jerusalem". Reuters. August 8, 2018 – via www.reuters.com.

- Murphy-O'Connor (2008), pp. 80–82

- The Palatial Mansion, Carta Publishing House, Jerusalem. Accessed 9 September 2020.

- Murphy-O'Connor (2008), p. 80

- "Were There Jewish Temples on Temple Mount? Yes". Haaretz. Retrieved 2022-01-11.

- "Collections | The Israel Museum, Jerusalem". www.imj.org.il.

- "Outside Jerusalem's Old City, a once-in-a-lifetime find of ancient Greek inscription". www.timesofisrael.com.

- "Important ancient inscription unearthed near the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem" – via www.youtube.com.

- Teller, Matthew (2022). Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City. Profile Books. p. Chapter 1. ISBN 978-1-78283-904-0. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

But it may not have been Aldrich and Symonds. Below the frame of their map, printed in italic script, a single line notes that 'The Writing' had been added by 'the Revd. G. Williams' and 'the Revd. Robert Willis'… Some sources suggest [Williams] arrived before [Michael] Alexander, in 1841. If so, did he meet Aldrich and Symonds? We don't know. But Williams became their champion, defending them when the Haram inaccuracy came up and then publishing their work. The survey the two Royal Engineers did was not intended for commercial release (Aldrich had originally been sent to Syria under 'secret service'), and it was several years before their military plan of Jerusalem came to public attention, published first in 1845 by their senior officer Alderson in plain form, without most of the detail and labelling, and then in full in 1849, in the second edition of Williams's book The Holy City. Did Aldrich and/or Symonds invent the idea of four quarters in Jerusalem? It's possible, but they were military surveyors, not scholars. It seems more likely they spent their very short stay producing a usable street-plan for their superior officers, without necessarily getting wrapped up in details of names and places. The 1845 publication, shorn of street names, quarter labels and other detail, suggests that… Compounding his anachronisms, and perhaps with an urge to reproduce Roman urban design in this new context, Williams writes how two main streets, north-south and east-west, 'divide Jerusalem into four quarters.' Then the crucial line: 'The subdivisions of the streets and quarters are numerous, but unimportant.' Historians will, I hope, be able to delve more deeply into Williams's work, but for me, this is evidence enough. For almost two hundred years, virtually the entire world has accepted the ill-informed, dismissive judgementalism of a jejune Old Etonian missionary as representing enduring fact about the social make-up of Jerusalem. It's shameful… With Britain's increased standing in Palestine after 1840, and the growth of interest in biblical archaeology that was to become an obsession a few decades later, it was vital for the Protestant missionaries to establish boundaries in Jerusalem… Williams spread his ideas around. Ernst Gustav Schultz, who came to Jerusalem in 1842 as Prussian vice-consul, writes in his 1845 book Jerusalem: Eine Vorlesung ('A Lecture'): 'It is with sincere gratitude I must mention that, on my arrival in Jerusalem, Mr Williams ... willingly alerted me to the important information that he [and] another young Anglican clergyman, Mr Rolands, had discovered about the topography of [Jerusalem].' Later come the lines: 'Let us now divide the city into quarters,' and, after mentioning Jews and Christians, 'All the rest of the city is the Mohammedan Quarter.' Included was a map, drawn by Heinrich Kiepert, that labelled the four quarters, mirroring Williams's treatment in The Holy City.

- Arnon 1992, pp. 5–7: "The origin of this ethno-religious partition lies in the nineteenth-century modern survey maps of Jerusalem drawn by Europeans – travellers, army officers, architects – who explored the city. The following verbal geographical definitions of the quarters will refer to this contemporarily prevailing division of the Old City. The ethno-religious partition of the Old City on the nineteenth-century maps reflected a situation rooted in history. Crusader Jerusalem of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the capital of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, was partitioned among the residential territories of people from different European countries, Oriental Christian communities and knights orders. In 1244 Jerusalem returned to Moslem hands when it became part of the Ayyubid Sultanate of Egypt. The change of government coincided with a devastation of the city by the Central Asian tribe of Khawarizm which all but annihilated the city's population. In 1250 the Mamluks rose to power in Egypt. Under their rule Jerusalem became a magnet to pilgrims from all parts of the Islamic world. People from various regions, towns and tribes settled in it. The parts of the city preferred by the Moslems were those adjoining the north and west sides of the Temple Mount (the other two sides lay outside the city) on which stood their two revered mosques, the Dome of the Rock and al-Agsa Mosque. Christians from different denominations resettled in the north-west of the city, at the vicinity of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Armenians settled in its south-west, near their Cathedral of St James which had been destroyd by the Khawarizms. Jews settled in Jerusalem, beginning with the second half of the thirteenth century, near the south wall of the city, because the territory there was not settled by any other community and separated from their venerated place, the West (Wailing) Wall, only by a small quarter of North-African Moslems. When the city changed hands again at the beginning of the sixteenth century, falling to the Ottoman Turks, no change in the city's population, and hence in its quarters occurred."

- Arnon 1992, pp. 12: "The continuous Moslem area of the city occupied its entire east half penetrating its west half at the north, near Damascus Gate. Excluding its south part and the north-west bulge, this region will be defined in the nineteenth century as the 'Moslem Quarter'. In the west part of the city lay Haret en-Nasara in the middle of the area which will be named in modern times the 'Christian Quarter'. Two minorities dwelt in the south outskirts of the city: Jews in Haret el-Yahud, in the south-west part of the future Jewish Quarter and Armenians around their monastery in the south part of the modern Armenian Quarter. The layout of ethno-religious groups in sixteenth-century Jerusalem agreed then with the guidelines of their dispersal in the city in the thirteenth century described above."

- Arnon 1992, pp. 16: "The continuous flow of Jews to Jerusalem since the 1840s (see below) caused Haret el-Yahud to extend to all the previously sparsely populated area south of Bab es-Silsila Street (except Haret el-Magharba) and the east part of the Armenian Quarter. Jews settled also north of Bab es-Silsila Street at the south part of the Moslem Quarter (see below). In fact, neither the traditional term 'Haret el-Yahud' nor its modern counterpart 'Jewish Quarter' could cope with the expansion of the area inhabited by Jews in the south of the Old City in the late nineteenth century. Northwards lay the two medieval quarters of Qattanin and 'Agabet et-Takiya which being called after subsidiary streets have been pushed along the years into the internal parts of the area west of the Temple Mount by two quarters named after main streets in that region and in the whole city, Wad and Bab es-Silsila."

- Arnon 1992, pp. 17: "The uniformity of the area inhabited by Moslems in the north of the city brought about, in the long run, the swallowing of the medieval-group-named quarters by the neighboring quarters called after sites. The great increase in Jewish population in modern times at the south of the city produced, on the other hand, a process in an opposite direction – a population-named quarter – Haret el-Yahud – extended to a quarter called after a site – Haret esh-Sharaf, populated in the Middle Ages by both Jews and Moslems. But unlike populations and their quarters which disappeared altogether from the city's scenery, 'Sharaf', since it was a name of a site, survived as the name of the street round which the quarter had developed. Hart el-Yahud expanded also to medieval quarters named after ethnic groups like Risha and Saltin. Other indications in quarter names of population changes between medieval and modern times were all unreal. These were the cases of Bani Zayd replaced by Sadiyya, Zara'na by Haddadin and part of Nasara by Mawarna. To complement the variations of quarter changes there were also modern quarters called after sites which partially replaced medieval site-named quarters – see Wad and Bab es-Silsila quarters before."

- Menachem Klein, 'Arab Jew in Palestine,' Israel Studies, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Fall 2014), pp. 134-153 p.139

- Arnon 1992, pp. 25–26.

- Discerning Conqueror, Haaretz

- "שבתי זכריה עו"ד חצרו של ר' משה רכטמן ברחוב מעלה חלדיה בירושלים העתיקה". Jerusalem-stories.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- Հայաստան սփյուռք [Armenia Diaspora] (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2013-05-11.

- Առաքելական Աթոռ Սրբոց Յակովբեանց Յերուսաղեմ [Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem (literally "Apostolic See of St. James in Jerusalem")] (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2011-07-09.

- University of Cape Town, Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Congress, South African Judaica Society 81(1986) (referencing archaeological evidence of "Israelite settlement of the Western Hill from the 8th Century BCE onwards").

- Simon Goldhill, Jerusalem: City of Longing 4 (2008) (conquered by "early Israelites" after the "ninth century B.C.")

- William G. Dever & Seymour Gitin (eds.), Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age Through Roman Palaestina 534 (2003) ("in the 8th–7th centuries B.C.E. ... Jerusalem was the capital of the Judean kingdom . ... It encompassed the entire City of David, the Temple Mount, and the Western Hill, now the Jewish Quarter of the Old City.")

- Hillel Geva (ed.), 1 Jewish Quarter Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem Conducted by Nahman Avigad, 1969–1982 81 (2000) ("The settlement in the Jewish Quarter began during the 8th century BCE. ... the Broad Wall was apparently erected by King Hezekiah of Judah at the end of the 8th century BCE.")

- Koert van Bekkum, From Conquest to Coexistence: Ideology and Antiquarian Intent in the Historiography of Israel’s Settlement in Canaan 513 (2011) ("During the last decennia, a general consensus was reached concerning Jerusalem at the end of Iron IIB. The extensive excavations conducted ... in the Jewish Quarter ... revealed domestic constructions, industrial installations and large fortifications, all from the second half of the 8th century BCE.")

- Mordechai Weingarten

- Dumper, Michael (2017). Najem, Tom; Molloy, Michael J.; Bell, Michael; Bell, John (eds.). Contested Sites in Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Old City Initiative. Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-317-21344-4.

- Staff. "Table III/14 – Population of Jerusalem, by Age, Quarter, Sub-Quarter, and Statistical Area, 2003" (PDF). Institute for Israel Studies (in Hebrew and English). Institute for Israel Studies, Jerusalem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Staff (2010). "Our communities". God's name to succeed (in Hebrew). World Karaite Judaism. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Nadav Shragai (8 March 2007). "The Gate of the Jews". Haaretz. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Steinberg, Gerald M. (2013). "False Witness? EU Funded NGOs and Policymaking in the Arab–Israeli Conflict" (PDF). Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs.

- Gülru Necipoğlu (2008). "The Dome of the Rock as a palimpsest: 'Abd al-Malik's grand narrative and Sultan Süleyman's glosses" (PDF). Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic. Leiden: Brill. 25: 20–21. ISBN 9789004173279. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

External links

- Virtual tour of the Old City's historic sites

- Virtual tour of the Muslim Quarter Archived 2017-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual tour of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre Archived 2007-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual tour of the Cardo Archived 2008-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual tour of the Damascus gate

- Virtual tour of the Kotel Archived 2008-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)