History of the Jews in France

The history of the Jews in France deals with Jews and Jewish communities in France since at least the Early Middle Ages. France was a centre of Jewish learning in the Middle Ages, but persecution increased over time, including multiple expulsions and returns. During the French Revolution in the late 18th century, on the other hand, France was the first European country to emancipate its Jewish population. Antisemitism still occurred in cycles and reached a high in the 1890s, as shown during the Dreyfus affair, and in the 1940s, under Nazi occupation and the Vichy regime.

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Total population | |

| Core Jewish population: 480,000–550,000[1][2][3][4][5] Enlarged Jewish population (includes non-Jewish relatives of Jews): 600,000[6][7] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Traditional Jewish languages Hebrew, Yiddish, Ladino, and other Jewish languages (most endangered and some now extinct) Liturgical languages Hebrew and Aramaic Predominant spoken languages French, Hebrew, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, and Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism or no religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, other ethnic divisions |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

Before 1919, most French Jews lived in Paris, with many being very proud to be fully assimilated into French culture, and they comprised an upscale subgroup. A more traditional Judaism was based in Alsace-Lorraine, which was taken by Germany in 1871 and recovered by France in 1918 following World War I. In addition, numerous Jewish refugees and immigrants came from Russia and eastern and central Europe in the early 20th century, changing the character of French Judaism in the 1920s and 1930s. These new arrivals were much less interested in assimilation into French culture. Some supported such new causes as Zionism, the Popular Front and communism, the latter two being popular among the French political left.

During World War II, the Vichy government collaborated with Nazi occupiers to deport a large number of both French Jews and foreign Jewish refugees to concentration camps.[8] By the war's end, 25% of the Jewish population of France had been murdered in the Holocaust, though this was a lower proportion than in most other countries under Nazi occupation.[9][10]

In the 21st century, France has the largest Jewish population in Europe and the third-largest Jewish population in the world (after Israel and the United States). The Jewish community in France is estimated to number 480,000–550,000, depending in part on the definition being used. French Jewish communities are concentrated in the metropolitan areas of Paris, which has the largest Jewish population (277,000),[11] Marseille, with a population of 70,000, Lyon, Nice, Strasbourg and Toulouse.[12]

The majority of French Jews in the 21st century are Sephardi and Mizrahi North African Jews, many of whom (or their parents) emigrated from former French colonies of North Africa after those countries gained independence in the 1950s and 1960s. They span a range of religious affiliations, from the ultra-Orthodox Haredi communities to the large segment of Jews who are entirely secular and who often marry outside the Jewish community.[13]

Approximately 200,000 French Jews live in Israel. Since 2010 or so, more have been making aliyah in response to rising antisemitism in France.[14]

Roman and Merovingian periods

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), "The first settlements of Jews in Europe are obscure. From 163 BCE there is evidence of Jews in Rome [...]. In the year 6 C.E. there were Jews at Vienne and Gallia Celtica; in the year 39 at Lugdunum (i.e. Lyon)".[15]

An early account praised Hilary of Poitiers (died 366) for having fled from the Jewish society. The emperors Theodosius II and Valentinian III sent a decree to Amatius, prefect of Gaul (9 July 425), that prohibited Jews and pagans from practising law or holding public offices (militandi). This was to prevent Christians from being subject to them and possibly incited to change their faith. At the funeral of Hilary, Bishop of Arles, in 449, Jews and Christians mingled in crowds and wept; the former were said to have sung psalms in Hebrew.[15]

In the sixth century, Jews were documented in Marseilles, Arles, Uzès, Narbonne, Clermont-Ferrand, Orléans, Paris, and Bordeaux. These cities had generally been centers of ancient Roman administration and were located on the great commercial routes. The Jews built synagogues in these cities. In harmony with the Theodosian code, and according to an edict of 331 by the emperor Constantine, the Jews were organized for religious purposes as they were in the Roman empire. They appear to have had priests (rabbis or ḥazzanim), archisynagogues, patersynagogues, and other synagogue officials. The Jews worked principally as merchants, as they were prohibited from owning land; they also served as tax collectors, sailors, and physicians.[15]

They probably remained under Roman law until the triumph of Christianity, with the status established by Caracalla, on a footing of equality with their fellow citizens. Their association with fellow citizens was generally amicable, even after the establishment of Christianity in Gaul. The Christian clergy participated in some Jewish feasts; intermarriage between Jews and Christians sometimes occurred; and the Jews made proselytes. Worried about Christians adopting Jewish religious customs, the third Council of Orléans (539) warned the faithful against Jewish "superstitions", and ordered them to abstain from traveling on Sunday and from adorning their persons or dwellings on that day. In the 6th century, a Jewish community thrived in Paris.[18] They built a synagogue on the Île de la Cité, but it was later torn down by Christians, who erected a church on the site.[18]

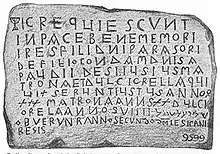

In 629, King Dagobert proposed the expulsion of all Jews who would not accept Christianity. No mention of the Jews was found from his reign to that of Pepin the Short. The Jews on the other hand continued to dwell and to prosper in what is now Southern France, then known as Septimania and a dependency of the Visigothic kings of Spain. From this epoch (689) dates the earliest known inscription relating to the Jews of France, the "Funerary Stele of Justus, Matrona and Dulciorella" of Narbonne, written in Latin and Hebrew.[15][16][17] The Jews of Narbonne, chiefly merchants, were popular among the people, who often rebelled against the Visigothic kings.[19]

Carolingian period

The presence of Jews in France under Charlemagne is documented, with their position being regulated by law. Exchanges with the Orient strongly declined with the presence of Arabs in the Mediterranean sea. Trading and importing of oriental products such as gold, silk, black pepper or papyrus almost disappeared under the Carolingians. The Radhanite Jewish traders were nearly the only group to maintain trade between the Occident and the Orient.[20]

Charlemagne fixed a formula for the Jewish oath to the state. He allowed Jews to enter into lawsuits with Christians. They were not allowed to require Christians to work on Sundays. Jews were not allowed to trade in currency, wine, or grain. Legally, Jews belonged to the emperor and could be tried only by him. But the numerous provincial councils which met during Charlemagne's reign were not concerned with the Jewish communities.

Louis the Pious (ruled 814–840), faithful to the principles of his father Charlemagne, granted strict protection to Jews, whom he respected as merchants. Like his father, Louis believed that 'the Jewish question' could be solved with the gradual conversion of Jews; according to medievalist scholar J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, some people believed this tolerance threatened the Christian unity of the Empire, which led to the strengthening of the Bishops at the expense of the Emperor. Saint Agobard of Lyon (779–841) had many run-ins with the Jews of France. He wrote about how rich and powerful they were becoming. Scholars such as Jeremy Cohen[21] suggest that Saint Agobard's belief in Jewish power contributed to his involvement in violent revolutions attempting to dethrone Louis the Pious in the early 830s.[22] Lothar and Agobard's entreaties to Pope Gregory IV gained them papal support for the overthrow of Emperor Louis. Upon Louis the Pious' return to power in 834, he deposed Saint Agobard from his see, to the consternation of Rome. There were unsubstantiated rumors in this period that Louis' second wife Judith was a converted Jew, as she would not accept the ordinatio for their first child.

Jews were engaged in export trade, particularly traveling to Palestine under Charlemagne. When the Normans disembarked on the coast of Narbonnese Gaul, they were taken for Jewish merchants. One authority said the Jewish traders boasted about buying whatever they pleased from bishops and abbots. Isaac the Jew, who was sent by Charlemagne in 797 with two ambassadors to Harun al-Rashid, the fifth Abbasid Caliph, was probably one of these merchants. He was said to have asked the Baghdad caliph for a rabbi to instruct the Jews whom he had allowed to settle at Narbonne (see History of the Jews in Babylonia).

Capetians

Persecutions (987–1137)

There were widespread persecutions of Jews in France beginning in 1007 or 1009.[23] These persecutions, instigated by Robert II (972–1031), King of France (987–1031), called "the Pious", are described in a Hebrew pamphlet,[24][25] which also states that the King of France conspired with his vassals to destroy all the Jews on their lands who would not accept baptism, and many were put to death or killed themselves. Robert is credited with advocating forced conversions of local Jewry, as well as mob violence against Jews who refused.[26] Among the dead was the learned Rabbi Senior. Robert the Pious is well known for his lack of religious tolerance and for the hatred which he bore toward heretics; it was Robert who reinstated the Roman imperial custom of burning heretics at the stake.[27] In Normandy under Richard II, Duke of Normandy, Rouen Jewry suffered from persecutions that were so terrible that many women, in order to escape the fury of the mob, jumped into the river and drowned. A notable of the town, Jacob b. Jekuthiel, a Talmudic scholar, sought to intercede with Pope John XVIII to stop the persecution in Lorraine (1007).[28] Jacob undertook the journey to Rome, but was imprisoned with his wife and four sons by Duke Richard, and escaped death only by allegedly miraculous means.[29] He left his eldest son, Judah, as a hostage with Richard while he and his wife and three remaining sons went to Rome. He bribed the pope with seven gold marks and two hundred pounds, who thereupon sent a special envoy to King Robert ordering him to stop the persecutions.[25][30]

If Adhémar of Chabannes, who wrote in 1030, is to be believed (he had a reputation as a fabricator), the anti-Jewish feelings arose in 1010 after Western Jews addressed a letter to their Eastern coreligionists warning them of a military movement against the Saracens. According to Adémar, Christians urged by Pope Sergius IV[31] were shocked by the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem by the Muslims in 1009. After the destruction, European reaction to the rumor of the letter was of shock and dismay, Cluniac monk Rodulfus Glaber blamed the Jews for the destruction. In that year Alduin, Bishop of Limoges (bishop 990–1012), offered the Jews of his diocese the choice between baptism and exile. For a month theologians held disputations with the Jews, but without much success, for only three or four of Jews abjured their faith; others killed themselves; and the rest either fled or were expelled from Limoges.[32][33] Similar expulsions took place in other French towns.[33] By 1030, Rodulfus Glaber knew more concerning this story.[34] According to his 1030 explanation, Jews of Orléans had sent to the East through a beggar a letter that provoked the order for the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Glaber adds that, on the discovery of the crime, the expulsion of the Jews was everywhere decreed. Some were driven out of the cities, others were put to death, while some killed themselves; only a few remained in the "Roman world". Count Paul Riant (1836–1888) says that this whole story of the relations between the Jews and the Mohammedans is only one of those popular legends with which the chronicles of the time abound.[35]

Another violent commotion arose at about 1065. At this date Pope Alexander II wrote to Béranger, Viscount of Narbonne and to Guifred, bishop of the city, praising them for having prevented the massacre of the Jews in their district, and reminding them that God does not approve of the shedding of blood. In 1065 also, Alexander admonished Landulf VI of Benevento "that the conversion of Jews is not to be obtained by force."[36] Also in the same year, Alexander called for a crusade against the Moors in Spain.[37]

Franco-Jewish literature

During this period, which continued until the First Crusade, Jewish culture flourished in the South and North of France. The initial interest included poetry, which was at times purely liturgical, but which more often was a simple scholastic exercise without aspiration, destined rather to amuse and instruct than to move. Following this came Biblical exegesis, the simple interpretation of the text, with neither daring nor depth, reflecting a complete faith in traditional interpretation, and based by preference on the Midrashim, despite their fantastic character. Finally, and above all, their attention was occupied with the Talmud and its commentaries. The text of this work, together with that of the writings of the Geonim, particularly their responsa, was first revised and copied; then these writings were treated as a corpus juris, and were commented upon and studied both as a pious exercise in dialectics and from the practical point of view. While most of the focus of Jewish authors was religious, they did discuss other subjects, like the papal presence in their communities.[38]

Rashi

The great Jewish figure who dominated the second half of the 11th century, as well as the whole rabbinical history of France, was Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki) of Troyes (1040–1105). He personified the genius of northern French Judaism: its devoted attachment to tradition; its untroubled faith; its piety, ardent but free from mysticism. His works are distinguished by their clarity, directness, and are written in a simple, concise, unaffected style, suited to his subject.[39] His commentary on the Talmud, which was the product of colossal labor, and which eclipsed the similar works of all his predecessors, by its clarity and soundness made the study of that vast compilation easy, and soon became its indispensable complement. Every edition of the Talmud that was ever published has this commentary printed on the same page of the Talmud itself. His commentary on the Bible (particularly on the Pentateuch), a sort of repertory of the Midrash, served for edification, but also advanced the taste for seeking the plain and true meaning of the bible. The school which he founded at Troyes, his birthplace, after having followed the teachings of those of Worms and Mainz, immediately became famous. Around his chair were gathered Simḥah b. Samuel, R. Shamuel b. Meïr (Rashbam), and Shemaya, his grandsons; likewise Shemaria, Judah b. Nathan, and Isaac Levi b. Asher, all of whom continued his work. The school's Talmudic commentaries and interpretations are the basis and starting point for the Ashkenazic tradition of how to interpret and understand the Talmud's explanation of Biblical laws. In many cases, these interpretations differ substantially from those of the Sephardim, which results in differences between how Ashkenazim and Sephardim hold what constitutes the practical application of the law. In his Biblical commentaries, he availed himself of the works of his contemporaries. Among them must be cited Moses ha-Darshan, chief of the school of Narbonne, who was perhaps the founder of exegetical studies in France, and Menachem b. Ḥelbo. Thus the 11th century was a period of fruitful activity in literature. Thenceforth French Judaism became one of the poles within Judaism.[39]

The Crusades

The Jews of France suffered during the First Crusade (1096),[40] when the crusaders are stated, for example, to have shut up the Jews of Rouen in a church and to have murdered them without distinction of age or sex, sparing only those who accepted baptism.[41] According to a Hebrew document, the Jews throughout France were at that time in great fear and wrote to their brothers in the Rhine countries making known to them their terror and asking them to fast and pray.[41] In the Rhineland, thousands of Jews were killed by the crusaders (see German Crusade, 1096).[42]

Jews did not have an active role in the Crusades, like Muslims and Christians did. Instead, Jews feared for their lives, as expulsions and anti-Jewish sentiment was on the rise in Western Europe. In 1256, around 3000 Jews were murdered in the French cities of Bretagne, Anjou, and Poitou. The violence and hatred spread by the pope encouraging violence led to the persecution of Jews in France. Many Jews fled to Narbonne, a city on the southwest coast of the country, which had long been a safe haven and center for Jewish life. The southern coast was more tolerant of Jewish life than the northern half of the country.[43]

Expulsion from France, 1182

The First Crusade led to nearly a century of accusations (blood libel) against the Jews, many of whom were burned or attacked in France. Immediately after the coronation of Philip Augustus on 14 March 1181, the King ordered the Jews arrested on a Saturday, in all their synagogues, and despoiled of their money and their investments. In the following April 1182, he published an edict of expulsion, but according to the Jews a delay of three months for the sale of their personal property. Immovable property, however, such as houses, fields, vines, barns, and wine presses, he confiscated. The Jews attempted to win over the nobles to their side but in vain. In July they were compelled to leave the royal domains of France (and not the whole kingdom); their synagogues were converted into churches. These successive measures were simply expedients to fill the royal coffers. The goods confiscated by the king were at once converted into cash.

During the century which terminated so disastrously for the Jews, their condition was not altogether bad, especially if compared with that of their brethren in Germany. Thus may be explained the remarkable intellectual activity which existed among them, the attraction that it exercised over the Jews of other countries, and the numerous works produced in those days. The impulse given by Rashi to study did not cease with his death; his successors—the members of his family first among them—continued his work. Research moved within the same limits as in the preceding century, and dealt mainly with the Talmud, rabbinical jurisprudence, and Biblical exegesis.[39]

Recalled by Philip Augustus, 1198

This century, which opened with the return of the Jews to France proper (then reduced almost to the Île de France), closed with their complete exile from the country in a larger sense. In July 1198, Philip Augustus, "contrary to the general expectation and despite his own edict, recalled the Jews to Paris and made the churches of God suffer great persecutions" (Rigord). The king adopted this measure from no good will toward the Jews, for he had shown his true sentiments a short time before in the Bray affair. But since then he had learned that the Jews could be an excellent source of income from a fiscal point of view, especially as money-lenders. Not only did he recall them to his estates, but he gave state sanction by his ordinances to their operations in banking and pawnbroking. He placed their business under control, determined the legal rate of interest, and obliged them to have seals affixed to all their deeds. Naturally, this trade was taxed, and the affixing of the royal seal was paid for by the Jews. Henceforward there was in the treasury a special account called "Produit des Juifs", and the receipts from this source increased continually. At the same time, it was in the interest of the treasury to secure possession of the Jews, considered a fiscal resource. The Jews were therefore made serfs of the king in the royal domain, just at a time when the charters, becoming wider and wider, tended to bring about the disappearance of serfdom. In certain respects their position became even harder than that of serfs, for the latter could in certain cases appeal to custom and were often protected by the Church; but there was no custom to which the Jews might appeal, and the Church laid them under its ban. The kings and the lords said "my Jews" just as they said "my lands", and they disposed in like manner of the one and of the other. The lords imitated the king: "they endeavored to have the Jews considered an inalienable dependence of their fiefs, and to establish the usage that if a Jew domiciled in one barony passed into another, the lord of his former domicil should have the right to seize his possessions." This agreement was made in 1198 between the king and the Count of Champagne in a treaty, the terms of which provided that neither should retain in his domains the Jews of the other without the latter's consent and furthermore that the Jews should not make loans or receive pledges without the express permission of the king and the count. Other lords made similar conventions with the king. Thenceforth they too had a revenue known as the Produit des Juifs, comprising the taille, or annual quit-rent, the legal fees for the writs necessitated by the Jews' law trials, and the seal duty. A thoroughly characteristic feature of this fiscal policy is that the bishops (according to the agreement of 1204 regulating the spheres of ecclesiastical and seigniorial jurisdiction) continued to prohibit the clergy from excommunicating those who sold goods to the Jews or who bought from them.[44]

The practice of "retention treaties" spread throughout France after 1198. Lords intending to impose a heavy tax (captio, literally "capture") on Jews living in their lordship (dominium) signed treaties with their neighbours, whereby the latter refused to permit the former's Jews entry into his domains, thus "retaining" them for the lord to tax. This practice arose in response to the common flight of Jews in the face of a captio to a different dominium, where they purchased the right to settle unmolested by gifts (bribes) to their new lord. In May 1210 the crown negotiated a series of treaties with the neighbours of the royal demesne and successfully "captured" its Jews with a large tax levy. From 1223 on, however the Count Palatine of Champagne refused to sign any such treaties, and in that year even refused to affirm the crown's asserted right to force non-retention policies on its barons. Such treaties became obsolete after Louis IX's ordinance of Melun (1230), when it became illegal for a Jew to migrate between lordships. This ordinance—the first piece of public legislation in France since Carolingian times—also declared it treason to refuse non-retention.[45]

Under Louis VIII

Louis VIII of France (1223–26), in his Etablissement sur les Juifs of 1223, while more inspired with the doctrines of the Church than his father, Philip Augustus, knew also how to look after the interests of his treasury. Although he declared that from 8 November 1223, the interest on Jews' debts should no longer hold good, he at the same time ordered that the capital should be repaid to the Jews in three years and that the debts due the Jews should be inscribed and placed under the control of their lords. The lords then collected the debts for the Jews, doubtless receiving a commission. Louis furthermore ordered that the special seal for Jewish deeds should be abolished and replaced by the ordinary one.

Twenty-six barons accepted Louis VIII's new measures, but Theobald IV (1201–53), the powerful Count of Champagne, did not, since he had an agreement with the Jews that guaranteed their safety in return for extra income through taxation. Champagne's capital at Troyes was where Rashi had lived a century before, and Champagne continued to have a prosperous Jewish population. Theobald IV would become a major opposition force to Capetian dominance, and his hostility was manifest during the reign of Louis VIII. For example, during the siege of Avignon, he performed only the minimum service of 40 days and left for home amid charges of treachery.

Under Louis IX

In spite of all these restrictions designed to restrain, if not to suppress moneylending, Louis IX of France (1226–70) (also known as Saint Louis), with his ardent piety and his submission to the Catholic Church, unreservedly condemned loans at interest. He was less amenable than Philip Augustus to fiscal considerations. Despite former conventions, in an assembly held at Melun in December 1230, he compelled several lords to sign an agreement not to authorize Jews to make any loan. No one in the whole Kingdom of France was allowed to detain a Jew belonging to another, and each lord might recover a Jew who belonged to him, just as he might his own serf (tanquam proprium servum), wherever he might find him and however long a period had elapsed since the Jew had settled elsewhere. At the same time, the ordinance of 1223 was enacted afresh, which only proves that it had not been carried into effect. Both king and lords were forbidden to borrow from Jews.

In 1234, Louis freed his subjects from a third of their registered debts to Jews (including those who had already paid their debts), but debtors had to pay the remaining two-thirds within a specified time. It was also forbidden to imprison Christians or to sell their real estate to recover debts owed to Jews. The king wished in this way to strike a deadly blow at usury.

In 1243, Louis ordered, at the urging of Pope Gregory IX, the burning in Paris of some 12,000 manuscript copies of the Talmud and other Jewish works.

In order to finance his first Crusade, Louis ordered the expulsion of all Jews engaged in usury and the confiscation of their property, for use in his crusade, but the order for the expulsion was only partly enforced if at all. Louis left for the Seventh Crusade in 1248.

However, he did not cancel the debts owed by Christians. Later, Louis became conscience-stricken, and, overcome by scruples, he feared lest the treasury, by retaining some part of the interest paid by the borrowers, might be enriched with the product of usury. As a result, one-third of the debts was forgiven, but the other two-thirds were to be remitted to the royal treasury.

In 1251, while Louis was in captivity on the Crusade, a popular movement rose up with the intention of traveling to the east to rescue him; although they never made it out of northern France, Jews were subject to their attacks as they wandered throughout the country (see Shepherds' Crusade).

In 1257 or 1258 ("Ordonnances", i. 85), wishing, as he says, to provide for his safety of soul and peace of conscience, Louis issued a mandate for the restitution in his name of the amount of usurious interest which had been collected on the confiscated property, the restitution to be made either to those who had paid it or to their heirs.

Later, after having discussed the subject with his son-in-law, King Theobald II of Navarre and Count of Champagne, Louis decided on 13 September 1268 to arrest Jews and seize their property. But an order which followed close upon this last (1269) shows that on this occasion also Louis reconsidered the matter. Nevertheless, at the request of Paul Christian (Pablo Christiani), he compelled the Jews, under penalty of a fine, to wear at all times the rouelle or badge decreed by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215. This consisted of a piece of red felt or cloth cut in the form of a wheel, four fingers in circumference, which had to be attached to the outer garment at the chest and back.

The Medieval Inquisition

The Inquisition, which had been instituted in order to suppress Catharism, finally occupied itself with the Jews of Southern France who converted to Christianity. The popes complained that not only were baptized Jews returning to their former faith but that Christians also were being converted to Judaism. In March 1273, Pope Gregory X formulated the following rules: relapsed Jews, as well as Christians who abjured their faith in favor of "the Jewish superstition", were to be treated by the Inquisitors as heretics. The instigators of such apostasies, as those who received or defended the guilty ones, were to be punished in the same way as the delinquents.

In accordance with these rules, the Jews of Toulouse, who had buried a Christian convert in their cemetery, were brought before the Inquisition in 1278 for trial, with their rabbi, Isaac Males, being condemned to the stake. Philip IV at first ordered his seneschals not to imprison any Jews at the instance of the Inquisitors, but in 1299 he rescinded this order.

The Great Exile of 1306

Toward the middle of 1306 the treasury was nearly empty, and the king, as he was about to do the following year in the case of the Templars, condemned the Jews to banishment, and took forcible possession of their property, real and personal. Their houses, lands, and movable goods were sold at auction; and for the king were reserved any treasures found buried in the dwellings that had belonged to the Jews. That Philip the Fair intended merely to fill the gap in his treasury, and was not at all concerned about the well-being of his subjects, is shown by the fact that he put himself in the place of the Jewish moneylenders and exacted from their Christian debtors the payment of their debts, which they themselves had to declare. Furthermore, three months before the sale of the property of the Jews the king took measures to ensure that this event should be coincident with the prohibition of clipped money, in order that those who purchased the goods should have to pay in undebased coin. Finally, fearing that the Jews might have hidden some of their treasures, he declared that one-fifth of any amount found should be paid to the discoverer. It was on 22 July, the day after Tisha B'Av, a Jewish fast day, that the Jews were arrested. In prison they received notice that they had been sentenced to exile; that, abandoning their goods and debts, and taking only the clothes which they had on their backs and the sum of 12 sous tournois each, they would have to quit the kingdom within one month. Speaking of this exile, a French historian has said,

In striking at the Jews, Philip the Fair at the same time dried up one of the most fruitful sources of the financial, commercial, and industrial prosperity of his kingdom.[46]

To a large extent, the history of the Jews of France ceased. The span of control of the King of France had increased considerably in extent. Outside the Île de France, it now comprised Champagne, the Vermandois, Normandy, Perche, Maine, Anjou, Touraine, Poitou, the Marche, Lyonnais, Auvergne, and Languedoc, reaching from the Rhône to the Pyrénées. The exiles could not take refuge anywhere except in Lorraine, the county of Burgundy, Savoy, Dauphiné, Roussillon, and a part of Provence—all regions located in Empire. It is not possible to estimate the number of fugitives; that given by Grätz, 100,000, has no foundation in fact.[47]

Return of the Jews to France, 1315

%252C_France_-_Mus%C3%A9e_d'art_et_d'histoire_du_Juda%C3%AFsme.jpg.webp)

Nine years had hardly passed since the expulsion of 1306 when Louis X of France (1314–16) recalled the Jews. In an edict dated 28 July 1315, he permitted them to return for a period of twelve years, authorizing them to establish themselves in the cities in which they had lived before their banishment. He issued this edict in answer to the demands of the people. Geoffrey of Paris, the popular poet of the time, says in fact that the Jews were gentle in comparison with the Christians who had taken their place, and who had flayed their debtors alive; if the Jews had remained, the country would have been happier; for there were no longer any moneylenders at all.[48] The king probably had the interests of his treasury also in view. The profits of the former confiscations had gone into the treasury, and by recalling the Jews for only twelve years he would have an opportunity for ransoming them at the end of this period. It appears that they gave the sum of 122,500 livres for the privilege of returning. It is also probable, as Adolphe Vuitry states, that a large number of the debts owing to the Jews had not been recovered, and that the holders of the notes had preserved them; the decree of return specified that two-thirds of the old debts recovered by the Jews should go into the treasury. The conditions under which they were allowed to settle in the land are set forth in a number of articles; some of the guaranties which were accorded the Jews had probably been demanded by them and been paid for.[49]

They were to live by the work of their hands or to sell merchandise of good quality; they were to wear the circular badge, and not discuss religion with laymen. They were not to be molested, either with regard to the chattels they had carried away at the time of their banishment, or with regard to the loans which they had made since then, or in general with regard to anything which had happened in the past. Their synagogues and their cemeteries were to be restored to them on condition that they would refund their value; or, if these could not be restored, the king would give them the necessary sites at a reasonable price. The books of the Law that had not yet been returned to them were also to be restored, with the exception of the Talmud. After the period of twelve years granted to them, the king might not expel the Jews again without giving them a year's time in which to dispose of their property and carry away their goods. They were not to lend on usury, and no one was to be forced by the king or his officers to repay to them usurious loans.

If they engaged in pawnbroking, they were not to take more than two deniers in the pound a week; they were to lend only on pledges. Two men with the title "auditors of the Jews" were entrusted with the execution of this ordinance and were to take cognizance of all claims that might arise in connection with goods belonging to the Jews that had been sold before the expulsion for less than half of what was regarded as a fair price. The king finally declared that he took the Jews under his special protection and that he desired to have their persons and property protected from all violence, injury, and oppression.

Expulsion of 1394

On 17 September 1394, Charles VI suddenly published an ordinance in which he declared, in substance, that for a long time he had been taking note of the many complaints provoked by the excesses and misdemeanors which the Jews committed against Christians; and that the prosecutors, having made several investigations, had discovered many violations by the Jews of the agreement they had made with him. Therefore, he decreed as an irrevocable law and statute that thenceforth no Jew should dwell in his domains ("Ordonnances", vii. 675). According to the Religieux de St. Denis, the king signed this decree at the insistence of the queen ("Chron. de Charles VI." ii. 119).[50] The decree was not immediately enforced, a respite being granted to the Jews in order that they might sell their property and pay their debts. Those indebted to them were enjoined to redeem their obligations within a set time; otherwise, their pledges held in pawns were to be sold by the Jews. The provost was to escort the Jews to the frontier of the kingdom. Subsequently, the king released the Christians from their debts.[51]

Provence

Archaeological evidence has been discovered of a Jewish presence in Provence since at least the 1st century. The earliest documentary evidence for the presence of Jews dates from the middle of the 5th century in Arles. The Jewish presence reached a peak in 1348 when it probably numbered about 15,000.[52]

Provence was not incorporated into France until 1481, and the expulsion edict of 1394 did not apply there. The privileges of the Jews of Provence were confirmed in 1482. However, from 1484, anti-Jewish disturbances broke out, with looting and violence perpetrated by laborers from outside the region hired for the harvest season. In some places, Jews were protected by the town officials, and they were declared to be under royal protection. However, a voluntary exodus began and was accelerated when similar disorders were repeated in 1485.[52] According to Isidore Loeb, in a special study of the subject in the Revue des Études Juives (xiv. 162–183), about 3,000 Jews came to Provence after the Alhambra Decree expelled Jews from Spain in 1492.

From 1484, one town after another had called for expulsion, but the calls were rejected by Charles VIII. However, Louis XII, in one of his first acts as king in 1498, issued a general expulsion order for the Jews of Provence. Though not enforced at the time, the order was renewed in 1500 and again in 1501. On this occasion, it was definitively implemented. The Jews of Provence were given the option of conversion to Christianity and a number chose that option. However, after a short while—if only to compensate partially for the loss of revenues caused by the departure of the Jews—the king imposed a special tax, referred to as "the tax of the neophytes." These converts and their descendants soon became the objects of social discrimination and slander.[52]

During the second half of the 17th century, a number of Jews attempted to reestablish themselves in Provence. Before the French Revolution abolished the administrative entity of Provence, the first community outside the southwest, Alsace-Lorraine and Comtat Venaissin, was re-formed in Marseilles.[52]

Early modern period

17th century

At the beginning of the 17th century Jews began again to re-enter France. This resulted in a new edict of 23 April 1615[53] which forbade Christians, under the penalty of death and confiscation, to shelter Jews or to converse with them.

Alsace was home to a significant number of Jews. In annexing the region in 1648, the French government was at first inclined toward the banishment of Jews living in those provinces but thought better of it in view of the benefit he could derive from them. On 25 September 1675, Louis XIV granted these Jews letters patent, taking them under his special protection. This, however, did not prevent them from being subjected to every kind of extortion, and their position remained the same as it had been under the Austrian government.

In 1683, Louis XIV expelled Jews from the newly acquired colony of Martinique. The Regency was no less severe.

Beginnings of emancipation

In the course of the 18th century, the attitude of the authorities toward Jews became more tolerant and corrected previous legislation. The authorities often overlooked infractions of the edict of banishment; a colony of Portuguese and German Jews was tolerated in Paris. The voices of enlightened Christians who demanded justice for the proscribed people began to be heard.

By the 1780s there were about 40,000 to 50,000 Jews in France, chiefly centered in Bordeaux, Metz, and a few other cities. They had very limited rights and opportunities, apart from the money-lending business, but their status was not illegal.[54] An Alsatian Jew named Cerfbeer, who had rendered great service to the French government as purveyor to the army, was the representantive of the Jews before Louis XVI. The humane minister, Malesherbes, summoned a commission of Jewish notables to make suggestions for the amelioration of the condition of their coreligionists. The direct result of the efforts of these men was the abolition, in 1785, of the degrading poll-tax and the permission to settle in all parts of France. Shortly afterward the Jewish question was raised by two men of genius, who subsequently became prominent in the French Revolution—Count Mirabeau and the Abbé Grégoire—the former of whom, while on a diplomatic mission in Prussia, had made the acquaintance of Moses Mendelssohn and his school (see Haskalah), who were then working toward the intellectual emancipation of the Jews. In a pamphlet, "Sur Moses Mendelssohn, sur la Réforme Politique des Juifs" (London, 1787), Mirabeau refuted the arguments of the German antisemites like Michaelis and claimed for the Jews the full rights of citizenship. This pamphlet naturally provoked many writings for and against the Jews, and the French public became interested in the question. On the proposition of Roederer the Royal Society of Science and Arts of Metz offered a prize for the best essay in answer to the question: "What are the best means to make the Jews happier and more useful in France?" Nine essays, of which only two were unfavorable to the Jews, were submitted to the judgment of the learned assembly. Of the challenge, there were three winners: Abbé Gregoire, Claude-Antoine Thiery, and Zalkind Hourwitz.

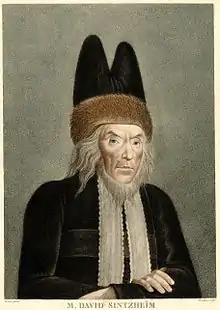

The Revolution and Napoleon

The Sephardi Jews in Bordeaux and Bayonne, who were willing to trade in their communal rights in exchange for full citizenship, participated in 1789 in the election of the Estates-General but those in Alsace, Lorraine, and in Paris, many of them Ashkenazi reluctant to yield to the state their intra-communal privileges, were denied this right. Herz Cerfbeer, a French-Jewish financier, then asked to Jacques Necker and obtained the right for Jews from eastern France to elect their own delegates.[55] Among them were the son of Cerfbeer, Theodore, and Joseph David Sinzheim. The Cahier written by the Jewish community from eastern France asked for the end of the discriminatory status and taxes targeting Jews.

The fall of the Bastille was the signal for disorders everywhere in France. In certain districts of Alsace the peasants attacked the dwellings of the Jews, who took refuge in Basel. A gloomy picture of the outrages upon them was sketched before the National Assembly (3 August) by the abbé Henri Grégoire, who demanded their complete emancipation. The National Assembly shared the indignation of the prelate, but left the question of emancipation undecided; it was intimidated by the deputies of Alsace, especially by Jean-François Rewbell.[55]

On 22 December 1789, the Jewish question came again before the Assembly in debating the issue of admitting to public service all citizens without distinction of creed. Mirabeau, the abbé Grégoire, Robespierre, Duport, Barnave and the comte de Clermont-Tonnerre exerted all the power of their eloquence to bring about the desired emancipation; but the repeated disturbances in Alsace and the strong opposition of the deputies of that province and of the clericals, like La Fare, Bishop of Nancy, the abbé Maury, and others, caused the decision to be again postponed. Only the Portuguese and the Avignonese Jews, who had hitherto enjoyed all civil rights as naturalized Frenchmen, were declared full citizens by a majority of 150 on 28 January 1790. This partial victory infused new hope into the Jews of the German districts, who made still greater efforts in the struggle for freedom. They won over the eloquent advocate Godard, whose influence in revolutionary circles was considerable. Through his exertions the National Guards and the diverse sections pronounced themselves in favor of the Jews, and the abbé Malot was sent by the General Assembly of the Commune to plead their cause before the National Assembly. The grave affairs which absorbed the Assembly, the prolonged agitations in Alsace, and the passions of the clerical party kept in check the advocates of Jewish emancipation. A few days before the dissolution of the National Assembly (27 September 1791) a member of the Jacobin Club, formerly a parliamentary councilor, Duport, unexpectedly ascended the tribune and said,

I believe that freedom of worship does not permit any distinction in the political rights of citizens on account of their creed. The question of the political existence of the Jews has been postponed. Still the Muslems and the men of all sects are admitted to enjoy political rights in France. I demand that the motion for postponement be withdrawn, and a decree passed that the Jews in France enjoy the privileges of full citizens.

This proposition was accepted amid loud applause. Rewbell endeavored, indeed, to oppose the motion, but he was interrupted by Regnault de Saint-Jean, president of the Assembly, who suggested "that every one who spoke against this motion should be called to order, because he would be opposing the constitution itself".

During the Reign of Terror

Judaism in France thus became, as the Alsatian deputy Schwendt wrote to his constituents, "nothing more than the name of a distinct religion". However, in Alsace, especially in the Bas-Rhin the reactionaries did not cease their agitations and Jews were victims of discriminations.[55] During the Reign of Terror, at Bordeaux, Jewish bankers, compromised in the cause of the Girondins, had to pay important fines or to run away to save their lives while some Jewish bankers (49 according to the Jewish Encyclopedia) were imprisoned at Paris as suspects and nine of them were executed.[56] The decree of the convention by which the Catholic faith was annulled and replaced by the worship of Reason was applied by the provincial clubs, especially by those of the German districts, to the Jewish religion as well. Some synagogues were pillaged and the mayors of a few eastern towns (Strasbourg, Troyes, etc.) forbade the celebration of Sabbath (to apply the week of ten days).[56]

Meanwhile, the French Jews gave proofs of their patriotism and of their gratitude to the land that had emancipated them. Many of them died in battle as part of the Army of the Republic while fighting the forces of Europe in coalition. To contribute to the war fund, candelabra of synagogues were sold, and wealthier Jews deprived themselves of their jewels to make similar contributions.

Attitude of Napoleon

Though the Revolution had begun the process of Jewish emancipation in France, Napoleon also spread the concept in the lands he conquered across Europe, liberating Jews from their ghettos and establishing relative equality for them. The net effect of his policies significantly changed the position of the Jews in Europe. Starting in 1806, Napoleon passed a number of measures supporting the position of the Jews in the French Empire, including assembling a representative group elected by the Jewish community, the Grand Sanhedrin. In conquered countries, he abolished laws restricting Jews to ghettos. In 1807, he added Judaism as an official religion of France, with previously sanctioned Roman Catholicism, and Lutheran and Calvinist Protestantism. Despite the positive effects, it is unclear however, whether Napoleon himself was disposed favorably towards the Jews, or merely saw them as a political or financial tool. On 17 March 1808, Napoleon rolled back some reforms by the so-called décret infâme, declaring all debts with Jews reduced, postponed, or annulled; this caused the Jewish community to nearly collapse. The decree also restricted where Jews could live, especially for those in the eastern French Empire, with all its annexations in the Rhineland and beyond (as of 1810), in hopes of assimilating them into society. Many of these restrictions were eased again in 1811 and finally abolished in 1818.

After the Restoration

The restoration of Louis XVIII did not materially change the political condition of the Jews. Enemies of the Jews cherished the hope that the Bourbons would hasten to undo the work of the Revolution with regard to Jewish emancipation, but were soon disappointed. The emancipation the French Jews had made enough progress that the clerical monarch could not find pretexts for curtailing their rights as citizens. They were no longer treated as poor, downtrodden peddlers or money-lenders with whom every petty official could do as he liked. Many of them already occupied high positions in the army and the magistracy, as well as in the arts and sciences.

State recognition

Of the faiths recognized by the state, only Judaism had to support its ministers, while those of the Catholic and Protestant churches were supported by the government. This legal inferiority was removed in 1831, thanks to the intervention of the Duke of Orléans, lieutenant-general of the kingdom, and to the campaign led in Parliament by the deputies comte de Rambuteau and Jean Viennet. Encouraged by these prominent men, the minister of education, on 13 November 1830, offered a motion to place Judaism upon an equal footing with Catholicism and Protestantism as regards support for the synagogues and for the rabbis from the public treasury. The motion was accompanied by flattering compliments to the French Jews, "who", said the minister, "since the removal of their disabilities by the Revolution, have shown themselves worthy of the privileges granted to them". After a short discussion the motion was adopted by a large majority. In January 1831, it passed in the Chamber of Peers by 89 votes to 57, and on 8 February it was ratified by King Louis Philippe, who from the beginning had shown himself favorable to placing Judaism on an equal footing with the other faiths. Shortly afterward the rabbinical college, which had been founded at Metz in 1829, was recognized as a state institution, and was granted a subsidy. The government likewise liquidated the debts contracted by various Jewish communities before the Revolution.

Full equality

Full equality did not occur until 1831. By the fourth decade of the nineteenth century, France provided an environment in which Jews took active and many times leading roles. The Napoleonic policy of carrières aux talents, or 'careers for the gifted', permitted French Jews to enter previously forbidden fields such as the arts, finance, trade, and government. For this they were never forgiven by primarily Royalist and Catholic antisemites.

Assimilation

While the Jews had become in other respects the equals of their Christian fellow citizens, the More Judaico oath continued to be administered to them, in spite of the repeated protestations of the rabbis and the consistory. It was only in 1846, owing to a brilliant defense speech by the Jewish lawyer Adolphe Crémieux before the Court of Nîmes in defense of a rabbi who had refused to take this oath, and to a valuable essay on the subject by Martin, a prominent Christian advocate of Strasburg, that the Court of Cassation removed this last remnant of the legislation of the Middle Ages. With this act of justice the history of the Jews of France merges into the general history of the French people. The rapidity with which many of them won affluence and distinction in the nineteenth century is without parallel. In spite of the deep-rooted prejudices which prevailed in certain classes of French society, many of them occupied high positions in literature, art, science, jurisprudence, the army—indeed, in every walk of life. In 1860, the Alliance Israelite Universelle was formed "to work everywhere for the emancipation and moral progress of the Jews; to offer effective assistance to Jews suffering from antisemitism; and to encourage all publications calculated to promote this aim."[57]

In 1870, the Crémieux decrees granted automatic French citizenship to the approximately 40,000 Jews of Algeria, at that time a French département, contrary to their Muslim neighbors.[58]

People of Jewish faith in France were becoming assimilated into their lives. After their Emancipation in 1791, Jews in France had new freedoms. For example, Jews were allowed to attend schools that were once delegated for just non-Jews. They were also allowed to pray in their own synagogues. Lastly, many Jews found themselves moving from the rural areas of France and into the big cities. In these big cities, Jews had new job opportunities and many were advancing up the economic ladder.

Although life was looking brighter for these Western Jews, some Jews who lived in Eastern Europe believed that the Emancipation in Western countries were causing the Jews to lose their traditional beliefs and culture. As more and more Jews were becoming assimilated into their new lives, these Jews were breaking away from rabbinical law and rabbinical authority decreased. For example, Jews were marrying outside of their religion and their children were growing up in homes where they were not being introduced to traditional beliefs and losing connection with their roots. Also, in these new urbanized Jewish homes, less and less Jews were following the strict rules of Kosher laws. Many Jews were so preoccupied with assimilating and prospering in their new lives that they formed a new type of Judaism that would fit with the times. The Reform Movement came about to let Jews stay connected to their roots while also living their lives without so many restrictions.

Antisemitism

Alphonse Toussenel (1803–1885) was a political writer and zoologist who introduced antisemitism into French mainstream thinking. A utopian socialist and a disciple of Charles Fourier, he criticized the economic liberalism of the July Monarchy and denounced the ills of civilization: individualism, egoism, and class conflict. He was hostile to the Jews and also to the British. Toussenel's Les juifs rois de l'époque, histoire de la féodalité financière (1845) argued that French finance and commerce was controlled by an alien Jewish presence, typified in the malign influence of the Rothschild banking family of France. Toussenel's antisemitism was rooted in a revolutionary-nationalist interpretation reading of French history. He was innovative and using zoology as a vehicle for social criticism, and his natural history books, as much as his political writings, were infused with antisemitic and anti-English sentiments. For Toussenel, the English and the Jews represented external and internal threats to French national identity.[59]

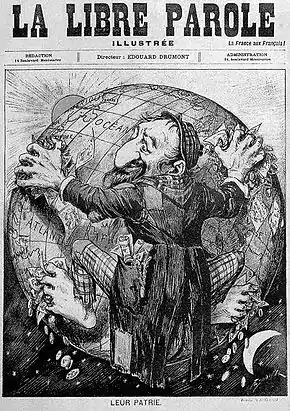

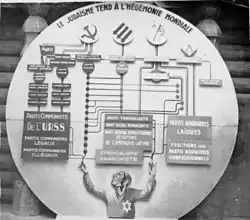

Antisemitism based on racism emerged in the 1880s led by Edouard Drumont, who founded the Antisemitic League of France in 1889, and was the founder and editor of the newspaper La Libre Parole. After spending years of research, he synthesized three major strands of antisemitism. The first strand was traditional Catholic attitudes toward the "Christ killers" augmented by vehement antipathy toward the French Revolution. The second strand was hostility to capitalism, of the sort promoted by the Socialist movement. The third strand was scientific racism, based on the argument that races have fixed characteristics, and the Jews have highly negative characteristics.[60][61]

Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair was a major political scandal that convulsed France from 1894 until its resolution in 1906, and which had reverberations for decades more. The affair is often seen as a modern and universal symbol of injustice for reasons of state[62] and remains one of the most striking examples of a complex miscarriage of justice where the press and public opinion played a central role. The issue was blatant antisemitism as practiced by the Army and defended by traditionalists (especially Catholics) against secular and republican forces, including most Jews. In the end, the latter triumphed, albeit at a very high personal cost to Dreyfus himself.[63][64]

The affair began in November 1894 with the conviction for treason of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent. He was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly having communicated French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris. Dreyfus was sent to the penal colony at Devil's Island in French Guiana, where he spent almost five years.

Two years later, in 1896, evidence came to light identifying a French Army major named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real spy. After high-ranking military officials suppressed the new evidence a military court unanimously acquitted Esterhazy after the second day of his trial. The Army accused Dreyfus of additional charges based on false documents. Word of the military court's framing of Dreyfus and of an attendant cover-up began to spread, chiefly owing to J'Accuse...!, a vehement open letter published in a Paris newspaper in January 1898 by the notable writer Émile Zola. Activists put pressure on the government to reopen the case.

In 1899, Dreyfus was returned to France for another trial. The intense political and judicial scandal that ensued divided French society between those who supported Dreyfus (now called "Dreyfusards"), such as Anatole France, Henri Poincaré and Georges Clemenceau, and those who condemned him (the anti-Dreyfusards), such as Édouard Drumont, the director and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole. The new trial resulted in another conviction and a 10-year sentence but Dreyfus was given a pardon and set free. Eventually, all the accusations against Alfred Dreyfus were demonstrated to be baseless. In 1906 Dreyfus was exonerated and reinstated as a major in the French Army.

The Affair from 1894 to 1906 divided France deeply and lastingly into two opposing camps: the pro-Army, mostly Catholic "anti-Dreyfusards" who generally lost the initiative to the anticlerical, pro-republican Dreyfusards. It embittered French politics and allowed the radicals to come to power.[65][66]

20th century

The relatively small Jewish community was based in Paris, and very well established in the city's business, financial, and intellectual elite. A third of Parisian bankers were Jewish, led by the Rothschild family, which also played a dominant role in the well organized Jewish community. Many of the most influential French intellectuals were nominally Jewish, including Henri Bergson, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl and Emile Durkheim. The Dreyfus affair to some degree rekindled their sense of being Jewish.[67] Jews were prominent in art and culture, typified by such artists as Modigliani, Soutine, and Chagall. The Jews considered themselves fully assimilated into French culture, for them Judaism was entirely a matter of religious belief, with minimal ethnic or cultural dimensions.[68]

By the time Dreyfus was fully exonerated in 1906, antisemitism declined sharply and it declined again during the First World War, as a nation was aware that many Jews died fighting for France. The antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole closed in 1924, and the former anti-Dreyfusard Maurice Barrès included Jews among France's "spiritual families".[69][70]

After 1900, a wave of Jewish immigrants arrived, mostly fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe. The flow temporarily halted during World War I but resumed afterwards. The long-established, heavily assimilated Jewish population by 1920 was now only a third of the French Jewish population. It was overwhelmed by new immigrants and the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine. About 200,000 immigrants arrived, 1900 to 1939, mostly Yiddish-speakers from Russia and Poland as well as German-speaking Jews who fled the Nazi regime after 1933. The historic base of traditional Judaism was in Alsace-Lorraine, which was recovered by France in 1918.

The new arrivals got along poorly with the established elite Jewish community. They did not want to assimilate, and they vigorously supported such new causes, especially Zionism and communism.[71] The Yiddish influx and the Jewishness of the Popular Front's leader Léon Blum contributed to a revival of antisemitism in the 1930s. Conservative writers such as Paul Morand, Pierre Gaxotte, Marcel Jouhandeau, and the leader of Action française Charles Maurras denounced Jews. Perhaps the most violent antisemitic writer was Louis-Ferdinand Céline, who wrote, "I feel myself very friendly to Hitler, and to all Germans, whom I feel to be my brothers.... Our real enemies are Jews and Masons", and "Yids are like bedbugs". By 1937, even mainstream French conservatives and socialists, not previously associated with antisemitism, denounced the alleged Jewish influence pushing the country into a "Jewish war" against Nazi Germany. The new intensity of antisemitism facilitated the extremism of the Vichy regime after 1940.[70]

World War II and the Holocaust

When France came under occupation by Nazi Germany in June 1940, about 330,000 Jews lived in France (and another 370,000 in never occupied French North Africa). Of the 330,000, fewer than half held French citizenship and the others were foreigners, mostly exiles from Germany and Central Europe who had immigrated to France during the 1930s.[8] Another 110,000 French Jews were living in the colony of French Algeria.[72]

About 200,000 Jews, and the large majority of foreign Jews, resided in the Paris area. Among the 150,000 French Jews, about 30,000, generally native to Central Europe, had recently obtained French citizenship after immigrating to France during the 1930s. Following the 1940 armistice after Germany invaded France, the Nazis incorporated the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine into Germany. The remainder of northern and western France was placed under German military control. Unoccupied southern metropolitan France and the French empire were placed under the control of the Vichy Regime, a new collaborationist French government. Some Jews managed to escape the invading German forces. Some found refuge in the countryside. Spain allowed 25,600 Jews to use its territory as an escape route.

German occupation forces published their first anti-Jewish measure on 27 September 1940 as the "First Ordinance." The measure was a census of Jews, and defined "who is a Jew." The Second Ordinance was published on 18 October 1940, proscribing various business activities for Jews. On 31 August 1941 German forces confiscated all radios belonging to Jews, followed by their telephones, their bicycles, and disconnecting all phones to Jews. They were forbidden to use public telephones. Jews were forbidden to change their address, and next were forbidden to leave their homes between 8 pm and 5 am. All public places, parks, theatres and certain shops were soon closed to Jews. German forces issued new restrictions, prohibitions and decrees by the week. Jews were barred from public swimming pools, restaurants, cafes, cinemas, concerts, music halls, etc. On the metro, they were allowed to ride only in the last carriage. Antisemitic articles were frequently published in newspapers since the Occupation. The Germans organized antisemitic exhibitions to spread their propaganda. The music of Jewish composers was banned, as were works of art by Jewish artists. On 2 October 1941, seven synagogues were bombed. Still, the vast majority of synagogues remained opened during the whole war in the Zone libre. The Vichy government even protected them after attacks as a way to deny persecution.[73]

The first roundup of Jews took place on 14 May 1941, and 4,000 foreign Jews were taken captive. Another roundup took place on 20 August 1941, collecting both French and foreign Jews, who were sent to the Drancy internment camp and other concentration camps in France. Roundups continued, collecting French nationals, including lawyers and other professionals. On 12 December 1941, the most distinguished members of the Paris Jewish community, including doctors, academics, scientists and writers, were rounded up. On 29 May 1942, the Eighth Ordinance was published, which ordered Jews to wear the yellow star. The most notorious roundup was the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup, which required detailed planning and the use of the full resources of French police forces. This roundup took place on 16 and 17 July 1942; it collected nearly 13,000 Jews, 7,000 of whom, including more than 4,000 children, were interned and locked into the Vélodrome d'Hiver, without adequate food or sanitation.

In the meantime, the Germans began deportations of Jews from France to the death camps in eastern Europe. The first trains left on 27 March 1942. Deportations continued until 17 August 1944, by which time nearly 76,000 Jews (including those from Vichy France) were deported, of whom only 2,500 survived. (see Timeline of deportations of French Jews to death camps.) The majority of Jews deported were non-French Jews.[8] One quarter of the pre-war Jewish population of France was killed in that process.

Antisemitism was particularly virulent in Vichy France, which controlled a third of France from 1940 to 1942, at which point the Germans took over that southern area. Vichy's Jewish policy was a mixture of 1930s antiforeigner legislation with the virulent antisemitism of the Action Française movement.[74] The Vichy government openly collaborated with the Nazi occupiers to identify Jews for deportation and transportation to the death camps. As early as October 1940, without any request from the Germans, the Vichy government passed anti-Jewish measures (the Vichy laws on the status of Jews), prohibiting them from moving, and limiting their access to public places and most professional activities, especially the practice of medicine. The Vichy government also implemented those anti-Jewish laws in the colonies of Vichy North Africa. In 1941, the Vichy government established the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, which in 1942 worked with the Gestapo to round-up Jews. They participated in the Vel' d'Hiv roundup on 16 and 17 July 1942.

On the other hand, France is recognised as the nation with the third highest number of Righteous Among the Nations (according to the Yad Vashem museum, 2006). This award is given to "non-Jews who acted according to the most noble principles of humanity by risking their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust."

In 1995 French President Jacques Chirac formally apologized to the Jewish community for the complicit role that French policemen and civil servants played in the roundups. He said:

- "These black hours will stain our history for ever and are an injury to our past and our traditions. Yes, the criminal madness of the occupant was assisted ('secondée') by the French, by the French state. Fifty-three years ago, on 16 July 1942, 450 policemen and gendarmes, French, under the authority of their leaders, obeyed the demands of the Nazis. That day, in the capital and the Paris region, nearly 10,000 Jewish men, women and children were arrested at home, in the early hours of the morning, and assembled at police stations... France, home of the Enlightenment and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, land of welcome and asylum, France committed that day the irreparable. Breaking its word, it delivered those it protected to their executioners."[75]

Chirac also identified those who were responsible: "450 policemen and gendarmes, French, under the authority of their leaders [who] obeyed the demands of the Nazis."

In July 2017, while at a ceremony at the site of the Vélodrome d'Hiver, France's President Emmanuel Macron denounced the country's role in the Holocaust and the historical revisionism that denied France's responsibility for 1942 roundup and subsequent deportation of 13,000 Jews (or the eventual deportation of 76,000 Jews). He refuted claims that the Vichy government, in power during WW II, did not represent the State.[76] "It was indeed France that organised this", French police collaborating with the Nazis. "Not a single German" was directly involved, he added.

Neither Chirac nor François Hollande had specifically stated that the Vichy government, in power during World War II, actually represented the French State.[77] Macron on the other hand, made it clear that the government during the War was indeed that of France. "It is convenient to see the Vichy regime as born of nothingness, returned to nothingness. Yes, it's convenient, but it is false. We cannot build pride upon a lie."[78][79]

Macron made a subtle reference to Chirac's 1995 apology when he added, "I say it again here. It was indeed France that organized the roundup, the deportation, and thus, for almost all, death."[80][81]

Post-World War II: Anti-discriminatory laws and migration

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish exodus from the Muslim world |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Antisemitism in the Arab world |

| Exodus by country |

| Remembrance |

| Related topics |

In the wake of the Holocaust, around 180,000 Jews remained in France, many of whom were refugees from Eastern Europe who either could not or would not return to their former home countries. To prevent the types of abuses that took place under the German Occupation and Vichy Regime, the legislature passed laws to suppress antisemitic harassment and actions, and established educational programs.

Jewish exodus from France's colonies in North Africa

The surviving French Jews were joined in the late 1940s, 1950s and 1960s by large numbers of Jews from France's predominantly Muslim North African colonies (along with millions of other French nationals) as part of the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries. They fled to France because of the decline of the French Empire and a surge in Muslim Antisemitism following the founding of Israel and Israel's victories in the Six-Day War and other Arab-Israeli wars.[47]

By 1951, France's Jewish population totalled around 250,000.[18] Between 1956 and 1967, about 235,000 Sephardi Jews from Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco and Egypt immigrated to France.

By 1968, Sephardi Jews from the former French possessions in North Africa constituted the majority of the Jews of France. Before World War II and the Holocaust, French Jews were predominately from the Ashkenazi tradition and culture. The Sephardim, who follow nusach sepharad (Judaism as per the Sephardic ritual, according to Dan Michman's definition of such Jews), have since had a significant influence on the nature of French Jewish culture. These Jews from French North Africa have generally enjoyed a successful social and economic integration and helped reinvigorate the country's Jewish community. Kosher restaurants and Jewish schools have multiplied, in particular since the 1980s. In part in response to internal and international events, many of the younger generations have committed to religious renewal.

In the 1980 Paris synagogue bombing, France's Jewish population suffered its first deadly terrorist attack since actions of the German occupation in the Second World War. The attack followed an increase in antisemitic incidents in the late 1970s by Neo Nazis.

France–Israel relations

Since World War II, France's government has varied in supporting and opposing the Israeli government. It was initially a very strong supporter of Israel, voting for its formation at the United Nations. It was Israel's main ally and primary supplier of military hardware for nearly two decades between 1948 and 1967.[82]

After the military alliance between France and Israel during the 1956 Suez Crisis, relations between Israel and France remained strong. It is widely believed that, as a result of the Protocol of Sèvres agreement, the French government secretly transported parts of its own atomic technology to Israel in the late 1950s which the Israeli government used to create nuclear weapons.[83]

But, after the end of the Algerian War in 1962, in which Algeria gained independence, France began to shift toward a more pro-Arab view. This change accelerated rapidly after the Six-Day War in 1967, in which the relations became strained. Following the war, the United States became Israel's main supplier of weapons and military technology.[82] After the 1972 Munich massacre at the Olympics, the French government refused to extradite Abu Daoud, one of the planners of the attack.[84] Both France and Israel participated in the 15-year-long Lebanese Civil War.

21st century

France has the largest Jewish population in Europe and the third largest Jewish population in the world (after Israel and the United States). The Jewish community in France is estimated from a core population of 480,000–500,000[1][2][3][4] to an enlarged population of 600,000.[6][7]

In 2009, France's highest court, the council of state issued a ruling recognising the state's responsibility in the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews during World War II. The report cited "mistakes" in the Vichy regime that had not been forced by the occupiers, stating that the state "allowed or facilitated the deportation from France of victims of anti-Semitism".[85][86]

Antisemitism and Jewish emigration

In the early 2000s, rising levels of antisemitism among French Muslims and antisemitic acts were publicized around the world,[87][88][89] including the desecration of Jewish graves and tensions between the children of North African Muslim immigrants and North African Jewish children.[90] One of the worst crimes happened when Ilan Halimi was mutilated and tortured to death by the so-called "Barbarians gang", led by Youssouf Fofana. This murder was motivated by money and fueled by antisemitic prejudices (the perpetrators said they believed Jews to be rich).[91][92] In March 2012, a gunman, who had previously killed three soldiers, opened fire at a Jewish school in Toulouse in an antisemitic attack, killing four people, including three children. President Nicolas Sarkozy said, "I want to say to all the leaders of the Jewish community, how close we feel to them. All of France is by their side."[93]

However, Jewish philanthropist Baron Eric de Rothschild suggested that the extent of antisemitism in France has been exaggerated and that "France was not an antisemitic country".[94] The Newspaper Le Monde Diplomatique had earlier said the same thing.[95] According to a 2005 poll made by the Pew Research Center, there is no evidence of any specific antisemitism in France, which, according to this poll, appears to be one of the least antisemitic countries in Europe,[96] though France has the world's third largest Jewish population.[1] France is the country that had the most favourable views of Jews in Europe (82%), next to the Netherlands, and the country with the third-fewest unfavourable views (16%) next to the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

Rises in antisemitism in modern France have been linked to the intensifying Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[97][98][99] Between the start of the Israeli offensive in Gaza in late December 2008 and its end in January 2009, an estimated hundred antisemitic acts were recorded in France. This compares with a total of 250 antisemitic acts in the whole of 2007.[97][100] In 2009, 832 acts of antisemitism were recorded in France (with, in the first half of 2009, an estimated 631 acts, more than the whole of 2008, 474), in 2010, 466 and, in 2011, 389.[101] In 2011, there were 260 threats (100 graffitis, 46 flyers or mails, 114 insults) and 129 crimes (57 assaults, 7 arsons or attempted arsons, 65 deteriorations and acts of vandalism but no murder, attempted murder or terrorist attack) recorded.[101]

Between 2000 and 2009, 13,315 French Jews moved to Israel, or made aliyah, an increase compared to the previous decade (1990–1999 : 10,443) that was in the continuity of a similar increase since the 1970s.[102] A peak was reached during this period, in 2005 (2005: 2,951 Olim) but a significant proportion (between 20 and 30%) eventually came back to France.[103] Some immigrants cited antisemitism and the growing Arab population as reasons for leaving.[89] One couple who moved to Israel claimed that rising antisemitism by French Muslims and the anti-Israel bias of the French government was making life for Jews increasingly uncomfortable for them.[104] At a welcoming ceremony for French Jews in the summer of 2004, then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon caused controversy when he advised all French Jews to "move immediately" to Israel and escape what he coined "the wildest anti-semitism" in France.[104][105][106][107] In August 2007, some 2,800 olim were due to arrive in Israel from France, as opposed to the 3,000 initially forecast.[108] 1,129 French Jews made aliyah to Israel in 2009 and 1,286 in 2010.[102]

However, in the long term, France is not one of the top countries of Jewish emigration toward Israel.[109] Many French Jews feel a strong attachment to France.[110] In November 2012, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in a joint press conference with François Hollande advised the French Jewish community by saying "In my role as Prime Minister of Israel, I always say to Jews, wherever they may be, I say to them: Come to Israel and make Israel your home." alluding to former Israel Prime Minister's Ariel Sharon's similar 2004 advisement towards the French Jewish community to move to Israel.[111] In 2013, 3,120 French Jews immigrated to Israel, marking a 63% increase over the previous year.[112]