John Cantiloe Joy and William Joy

The brothers John Cantiloe Joy (4 June 1805 – 10 August 1859), and William Joy (4 November 1803 – 22 March 1865), were English marine artists, who lived and worked together. They belonged to the Norwich School of painters, considered to be a unique phenomenon in the history of British art and the most important school of painting of 19th century England.

John Cantiloe Joy | |

|---|---|

Royal Navy shipping in the Channel (undated) | |

| Born | 4 June 1805 |

| Died | 10 August 1859 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Marine painting |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

William Joy | |

|---|---|

Saving a Crew near Yarmouth Pier (undated, Norfolk Museums Collections) | |

| Born | 4 November 1803 |

| Died | 22 March 1865 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Marine painting |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

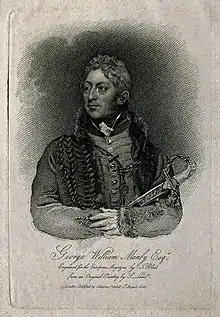

Born in Southtown (now a part of Great Yarmouth) in the English county of Norfolk, and from a working-class background, they were both expected to become tradesmen. Their talents were recognised by the inventor George William Manby, who became their patron and mentor. In 1818, he provided them with a studio, and trained them to become skilled marine artists. After two years, Manby mounted an exhibition of their work. During the 1820s, the brothers' paintings were exhibited at the Norwich Society of Artists, the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Academy and at the British Institution. William moved to London in 1829, where he was commissioned to produce new works; John joined him in London by the following year. In 1832, they moved to Portsmouth to record the area's fishing fleet for the British Government, and then moved to work in Chichester, before finally returning to London. There is some confusion among sources as to the dates of death of the two brothers: John's death is variously stated as occurring in 1857, 1866 or 1859, and that he predeceased William, who may have died in 1867, or in Yorkshire in 1865. However, death certificates confirm their deaths in 1859 and 1865 respectively.

William Joy enjoyed depicting powerful, raging seas and storm-tossed ships: John Joy painted in watercolours and his works are often less dramatic than those of his brother. Most of their publicly owned paintings belong to the Norfolk Museums Collections, based in Norwich.

Background

The Norwich School of painters, to which the Joy brothers belonged, was, according to the art historian Harold Day, "the most important School of Painting to develop in nineteenth century England".[1] The school was an important phenomenon in the history of 19th-century British art,[2] and Norwich was the first English city outside London where such a school arose.[3] Its artists were connected by geographical location, the depiction of Norwich, maritime scenes and rural Norfolk, and by close personal and professional relationships. The two most important members of the group were John Crome and John Sell Cotman; other prominent artists included George Vincent, Robert Ladbrooke, James Stark, Edward Thomas Daniell and John Thirtle.[4]

William and John Joy depicted nautical life of all kinds. During the 18th and 19th centuries, they and other English marine painters were influenced by Dutch and Flemish masters, whose seascapes were as much admired as their landscape subjects. These works were more often of non-military subjects such as world exploration, commercial shipping and fishing boats. They were produced by watercolourists, who only needed paper, drawing materials and watercolour pigments. The Joys' rapport with Dutch sea paintings was due in part to their upbringing in Great Yarmouth.[5]

Lives

Early years

William Joy was born in Southtown, Great Yarmouth,[6] on 4 November 1803, the son of John Joy and Elizabeth ('Betty') Cantiloe. His younger brother John Cantiloe Joy was born on 4 June 1805. The brothers remained close all their lives.[7]

The Joy children originated from a working-class background: their father was employed for 26 years as a guard on the Ipswich mail coach to and from Great Yarmouth.[8][9] He was possibly an amateur painter himself,[7][note 1] and the antiquarian John Chambers wrote that "his natural understanding was so excellent, and his knowledge of the powers of mechanism so correct, that... ...he was frequently accompanied ... outside the coach for the sole purpose of gaining information from his conversation". According to Chambers, "Mr. Joy was also highly susceptible of the sublime and beautiful in nature: and it was from his criticism on the effect of light and shade, as relative to the picturesque at sea, that led to a confession that he had two sons who were beginning to paint from nature."[8]

The boys attended Mr. Wright's Academy at Stone Cottage at the south-east end of Southtown.[11][12] They developed their early interest in drawing there, and sketched the school,[13] the earliest surviving examples of their work being six Select views in the Grounds of Mr. Wright's Academy Southtown Gt. Yarmouth, engraved by J. Lambert in 1820.[14]

Artistic training

The boys' artistic talents[7] caused them to be befriended by Captain George William Manby,[6] the barrack-master at Yarmouth's Royal Barracks,[note 2] and the inventor of the Manby mortar.[10] They may have met in 1818 when William first exhibited his work.[16] Manby used his money and influence to act as the Joys' patron, with the intention of gaining recognition for his invention.[17] In 1818 he provided them with studio space at the barracks,[18] and trained them to become skilled in depicting sailing ships.[6][7] Chambers noted that "he had a room fitted up for them, from which was an expansive view of the ocean, and from which might be seen all the variety of the sublime changes of its appearance, the hues produced on it by reflected clouds, with the ever varying character of the vessels which ploughed its surface".[19] Manby allowed them to his paintings by Nicholas Pocock and Francesco Francia,[7][13] and urged them to study from nature.[20]

The brothers' nurturing by Manby caused them to be isolated from other artists, including John Sell Cotman, who lived nearby. Largely self-taught, their reliance on each other served to increase their artistic isolation.[20]

In 1820 their work was exhibited at the barracks, an event which launched their artistic careers,[16][note 3] and which produced comments in the local press for the first time.[21] As John was 14 at the time, it is unlikely that any of the works were his.[22]

Manby's patronage occurred during the same period that the botanist and art collector Dawson Turner, Manby's friend and financial supporter for almost 50 years, was the patron of Cotman. Turner, who never seemed to have seriously considered buying the works of painters from the Norwich School except those of John Crome, is not known to have bought paintings from either Cotman or the Joys.[18]

Manby's sketches of a whaling trip to Greenland were used by William Joy to paint scenes of the Greenland Whale Fishery, that were later included in Manby's Journal of a Voyage to Greenland (1822).[23] An early attempt to paint in watercolours was their depiction of the yacht HMS Royal Sovereign in 1822, as it passed Yarmouth on its passage to Scotland, George IV being aboard.[24][note 4] They depicted the Lord High Admiral, the Duke of Clarence, visiting his son on board HMS Euryalus at Spithead, which helped to bring them recognition within naval circles.[24]

Careers prior to leaving Great Yarmouth

William, John and their sister Caroline lived in Great Yarmouth for many years, the brothers chiefly producing watercolours.[25] A number of picture collectors in the town actively purchased contemporary art, including paintings by the Joy brothers.[18] They included the Lacon family of Ormesby,[26] the Reverend John Homfray,[27] Mr. Croker, Mr. Freeling and Mr. F. Turner.[28] Although known as marine painters, the Joys also produced landscape sketches, some of which are in public collections.[29]

The Norwich Society of Artists was associated with the Norwich School of painters. The Joy brothers were not themselves members of the Society,[30] but its annual exhibitions in 1823, 1824, 1825 and 1828 included a number of John Joy's paintings, whilst William exhibited works at its exhibitions in 1819, and from 1823 to 1825.[31]

An artist named Caroline Joy was listed as an exhibitor in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition catalogues in 1845 and 1855.[32]

Work in London, Portsmouth and Chichester

William Joy travelled to London in 1829, armed with letters of introduction provided by Captain Manby.[16] He was introduced to Rear-Admiral Sir Charles Cunningham and Captain Edward Pelham Brenton, and received commissions from both men. A letter from Captain Manby to Dawson Turner reveals that Cunningham promised his support for Joy, and that in Manby's opinion, "Joy is now well on the road to fame and fortune, and will do honour not only to his native town but also to his country".[14] By November 1830 John had joined his brother, after which Manby's role as their mentor and patron came to an end.[33] With the assistance of the Earl of Abergavenny, they were able to obtain work,[13] and were for a period employed as artists by a Mr. Pearce of Conduit Street.[19]

In 1832 the Joys moved to Portsmouth, to depict the port's various fishing boats for the British Government,[16][34] and to improve their prospects.[20] No information about their work done there has emerged: neither of the Joys appear on the Navy Lists as government employees, or in the Imperial Calendars or the Naval Indexes and Digests, unlike other artists such as J.C. Sketchy, recorded as the Professor of Drawing at the Royal Naval College at Portsmouth from 1811 to 1836.[35]

They then worked in Chichester, before returning to live in London. They were listed together under the 'Professors and Teachers' section for the town in Pigot's Sussex Directory 1832–4, when they were living in Summerstown.[36] William Joy's last exhibited picture was at the British Institution, in 1845, when he was recorded as living in the town.[22] In London, John Joy was involved with producing illustrations for a history of the Tower of London.[37]

Final years

There is some confusion among sources as to the dates of death of the two brothers. Andrew Moore notes that after 1859, no dated paintings were produced by the Joys.[22] Redgrave, writing in 1878, gave John's date of death as 1857,[25] while Walpole gives 1866.[7] However, parish records for Lambeth indicate that John Cantiloe Joy died there in 1859,[38] and this is confirmed by a death certificate which gives details of the death of a marine artist of that name.

William's date of death is given as 1865 by the Victoria and Albert Museum website,[39] whilst the historian Josephine Walpole,[7] the Tate Museum website,[40] and the Survey of London (volume 21, published in 1949),[41] all state that he died in 1867. However, records from the 1861 United Kingdom census show that a man named William Joy was residing at Tancred's Hospital in Yorkshire that year, the record describing him as a marine artist, born in Great Yarmouth, aged 57, and unmarried.[42][note 5] Parish records for the village of Whixley show that a 61-year-old resident of Whixley called William Joy was buried on 25 March 1865[47] and his death certificate describes him as "formerly an artist in London".

Artistic output

Art historians now consider most of the Joys' paintings to have been produced individually.[48] Many of their works were unsigned, or the word 'JOY' was included on the side of a boat in a painting,[28] but Josephine Walpole believes it is quite possible to tell the brothers apart,[49] and Andrew Moore considers the notion that they worked jointly on a picture as an unfounded tradition.[22] A single painting is known to have been signed by both artists.[20] According to the English lawyer and historian Charles Palmer, the commissions the brothers obtained helped them to gain a reputation amongst nautical men for the way they accurately depicted the sails and rigging of a ship.[24]

John exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists from 1826 to 1827, whilst William exhibited pictures at the Royal Society, the Royal Academy and at the British Institution, from 1823 to 1845.[34][25]

William Joy's growing recognition in Great Yarmouth was mentioned in Druery's account of a local art collection, when he wrote, "...this would be an excellent and appropriate situation for a series of marine paintings by that eminent artist, William Joy, of Great Yarmouth...".[18] His paintings can be the easier to identify, as they are sometimes signed 'W. Joy'. His watercolours and oils have palettes that often include blues, greys, blacks and dark greens, as well as indigo, a pigment which faded over time.[49] He depicted powerful, raging seas, whipped-up foam and storm-tossed ships:[49] The writer Charlotte Miller praises his "gift for capturing the stark horror of disaster at sea".[20] The writer Michael Spender described Joy's work as "undemonstrative and accurate in its nautical detail".[5] His paintings have been compared with Joseph Stannard and Charles Brooking, but according to Walpole, his works lack Stannard's "personal charisma".[49]

John Joy painted in watercolours.[6] His palette contains delicate sepia and rich ochre tones,[28] his works are less dramatic than his brother's, and he tended to depict human figures more often.[50] According to Moore, he learnt from his elder brother.[22]

Walpole has described the Joys' later works as "more pictorial", perhaps as a result of being forced to follow the demands of their buyers, or because they had started to exhaust their subject after forty years.[50] Miller has suggested that the Joys may have found it difficult to adapt to depicting modern coal-powered iron ships, and that their aspirations were more limited than others, such as George Chambers, J.W. Carmichael or Clarkson Stanfield.[20]

Legacy

Paintings by the Joy brothers were included in an 1860 exhibition of paintings by deceased artists from the Norwich School of painters,[20] as well as in 1881, when an exhibition of their paintings entitled Wooden Walls of Old England was held at the Gladwell Brothers' gallery in Gracechurch Street, London.[51]

Examples of their works are held in the Norfolk Museums Collections based at the Norwich Castle Museum, some of which are on permanent display at the Tide and Time Museum in Great Yarmouth. Other paintings are held in the National Maritime Museum and in art galleries and museums in Portsmouth, Poole, King's Lynn, Birkenhead and Grimsby.[52][53] Several of the Joys' paintings have been sold at auction in recent years. Their undated H.M.S. Trafalgar and H.M.S. St. Vincent at Spithead (22.8 x 33 cm), which was sold at Christie's in 2014, fetched £2,375,[54] and a pair of watercolour paintings depicting fishermen, boats and sailors was sold at Keys Auctioneers of Aylsham in 2017 for £200.[55]

Gallery

A juvenile work by William Joy: In Felbrig Park (1816)

A juvenile work by William Joy: In Felbrig Park (1816) William Joy, A Lugger Driving Ashore in a Gale (Yale Center for British Art)

William Joy, A Lugger Driving Ashore in a Gale (Yale Center for British Art) William Joy, H.M. George IV passing Yarmouth on his return from Edinburgh, 1822 (Victoria & Albert Museum)

William Joy, H.M. George IV passing Yarmouth on his return from Edinburgh, 1822 (Victoria & Albert Museum) William Joy and John Cantiloe Joy, Louis Philippe, King of the French, Arriving at Portsmouth (1844), Tate Museums

William Joy and John Cantiloe Joy, Louis Philippe, King of the French, Arriving at Portsmouth (1844), Tate Museums John Cantiloe Joy, A British 1st Rate Ship of the Line Hove to (undated)

John Cantiloe Joy, A British 1st Rate Ship of the Line Hove to (undated) William Joy, Shipping off the coast at dusk (undated)

William Joy, Shipping off the coast at dusk (undated) John Cantiloe Joy, Going to a Vessel requiring assistance and Thereby preventing Shipwreck (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections

John Cantiloe Joy, Going to a Vessel requiring assistance and Thereby preventing Shipwreck (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections.jpg.webp) undated sketch, signed Mr. W. Joy, North Street, Chichester

undated sketch, signed Mr. W. Joy, North Street, Chichester William Joy, N.W. View of Yarmouth Jetty (c.1850s), Victoria and Albert Museum

William Joy, N.W. View of Yarmouth Jetty (c.1850s), Victoria and Albert Museum William and John Cantiloe Joy, (undated) Small craft running out of Portsmouth Harbour, Fort Blockhouse beyond

William and John Cantiloe Joy, (undated) Small craft running out of Portsmouth Harbour, Fort Blockhouse beyond William Joy, Shipwreck, the sun breaking through the clouds after the storm (1859)

William Joy, Shipwreck, the sun breaking through the clouds after the storm (1859) William Joy - Shipping at the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour

William Joy - Shipping at the entrance to Portsmouth Harbour

Notes

- The art historian Derek Clifford suggested that William and John's father was possibly R.B. Joy, who was known to be a member of the Norwich Society of Artists from 1808 to 1810.[10]

- The Royal Naval Hospital in Great Yarmouth was built in 1809-11 but became surplus to requirements following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The Admiralty then authorised its conversion into army barracks. By 1826 it had become unoccupied. It later became a military lunatic asylum before becoming a convalescent home, a naval base, and a psychiatric hospital. In 1996 the premises were converted into residential apartments.[15]

- Chambers' contemporary account provides a detailed snapshot of the brothers' artistic progress prior to becoming professional marine artists. An extract from his book praised them and provided advice for the young brothers: "Water in motion is more particularly the forte of William Joy, and in this department of his art, so difficult to painters in general, he has few superiors: the younger Joy exercises his talents in water colours, and both possess the qualifications of correct arrangement and excellent composition, combined with minute accuracy of representation, both in the drawing of vessels, and their lagging: and while they are making rapid progress as artists, they are not unmindful to whom they owe the excellence of their talents. All these young men now want, is a reference to, and permission to copy, the works of the most eminent masters, to enable them to do honour to the profession of the fine arts of this country; and to be the means of exciting genius in the humble walks of life to that exertion of industry which is sure to meet with encouragement."[8]

- The Joys' painting of the Royal Sovereign was purchased by its commander, Edward Owen.[24]

- Tancred's Hospital (also known as Whixley Hospital or Whixley Hall) was named after Christopher Tancred (1680–1754),[43] who bequeathed that his home should become an almshouse, where the pensioners were to be cared for by a housekeeper and a few servants.[44] The original foundation records state that the twelve pensioners were to be "decayed and necessitated gentlemen, clergymen, commissioned officers or sea officers". Further stipulations were that to become a Tancred's Pensioner they had to be British, Anglican, and unmarried, and could not be younger than 50 years old upon admission.[45][46]

References

- Day 1979, p. 7.

- Moore 1985, p. 9.

- Cundall & Holme 1920, p. 1.

- Cundall & Holme 1920, pp. 3–5.

- Spender 1987, p. 96.

- Day 1979, p. 171.

- Walpole 1997, p. 146.

- Chambers 1829, p. 313.

- Palmer 1875, p. 278.

- Clifford 1965, p. 51.

- Preston 1819, p. 247.

- "Farewell to Ferryside long-time register office". Great Yarmouth Mercury. 7 October 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Cust 1892, p. 217.

- Moore 1985, pp. 112–113.

- Davies 2015, p. 79.

- Walpole 1997, p. 147.

- Chambers 1829, pp. 313–314.

- Moore 1985, p. 112.

- Chambers 1829, p. 314.

- Miller 1977.

- Moore 1985, p. 117.

- Moore 1985, p. 114.

- Moore 1985, pp. 112–3.

- Palmer 1875, p. 279.

- Redgrave 1878, p. 244.

- Druery 1826, pp. 81–82.

- Druery 1826, pp. 119–120.

- Day 1979, p. 173.

- Clifford 1965, p. 52.

- Moore 1985, p. 118.

- Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 61.

- "Index". The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769-2018. Royal Academy. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Moore 1985, pp. 113.

- Redgrave 1893, p. 115.

- Miller 1977, p. 38.

- "Pigot's Sussex Directory, 1832–34". Historical Directories of England & Wales. University of Leicester. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Manuscript of "some account of the Tower of London", containing a brief history and physical description of the Tower, with three illustrations, by John Cantiloe Joy (1806–66), marine painter and topographical draughtsman". London Metropolitan Archives. City of London. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "William Joy in "England and Wales Census, 1851"". FamilySearch. 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019. (registration required)

- "The Jetty, Yarmouth, Norfolk". Victoria and Albert Museum. 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "William Joy". Tate. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Fitzroy Square". British History Online. University of London. 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Results for Census, land & surveys". Findmypast. 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Carr, William (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 352–3.

- Historic England (2019). "Whixley Hall (1149939)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- "Records of Tancred's Foundation, Whixley". Library. University of Leeds. 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Chambers & Chambers 1857, p. 385.

- "Yorkshire Burials (Whixley, 1865)". Findmypast. 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 146–7.

- Walpole 1997, pp. 147–8.

- Walpole 1997, p. 148.

- Huish 1882, p. 49.

- Richard Gardner Antiques website

- Wright 2006, p. 473.

- "H.M.S. Trafalgar and H.M.S. St. Vincent at Spithead". Christie's. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Lot 1374". Keys Auctioneers. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

Bibliography

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cust, Lionel Henry (1892). "Joy, William (1803-1867)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 217.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cust, Lionel Henry (1892). "Joy, William (1803-1867)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 217.

- Chambers, John (1829). A general history of the county of Norfolk. Vol. I. Norwich: John Stacey. LCCN 02029128.

- Chambers, Robert; Chambers, William (1857). Chambers's Edinburgh journal. Vol. VII. London and Edinburgh.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Clifford, Derek Plint (1965). Watercolours of the Norwich School. Cory, Adams & Mackay. OCLC 1624701.

- Cundall, Herbert Minton; Holme, Geoffrey (1920). The Norwich School. The Studio. London: Geoffrey Holme Ltd. OCLC 472125860.

- Davies, Paul P. (2015). More plaques in and around Great Yarmouth and Gorleston. Great Yarmouth Local History and Archaeological Society. ISBN 978-1-944241-98-8.

- Day, Harold (1979). The Norwich School of Painters. Eastbourne, UK: Eastbourne Fine Art. ISBN 978-0-902010-10-9.

- Druery, John Henry (1826). Historical and Topographical Notices of Great Yarmouth, in Norfolk, and Its Environs. London: Baldwin, Cradock & Joy. OCLC 23457363.

- Huish, Marcus B. (1882). The Year's Art 1882. London: Sampson Low et al. LCCN 08036871.

- Miller, Charlotte (6 October 1977). "Paintings' Elusive Joys: Two Norfolk Marine-Artist Brothers". Country Life. TI Media Ltd.

- Moore, Andrew W. (1985). The Norwich School of Artists. HMSO/Norwich Museums Service. ISBN 978-0-11-701587-6.

- Palmer, Charles John (1875). The Perlustration of Great Yarmouth, with Gorleston and Southtown. Vol. III. Great Yarmouth: George Nall. OCLC 3850725.

- Preston, John (1819). The picture of Yarmouth: being a compendious History and Description of all the public establishments within that Borough; together with a concise topographical account of ancient and modern Yarmouth, including its fisheries, etc., etc. Great Yarmouth: C, Sloman. OCLC 23457435.

- Rajnai, Miklos; Stevens, Mary (1976). The Norwich Society of Artists, 1805–1833: a dictionary of contributors and their work. Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. ISBN 978-0-903101-29-5.

- Redgrave, Richard (1893). A Catalogue of the National Gallery of British Art at South Kensington. Vol. Part I: Oil Paintings. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode. p. 115. OCLC 1008543107.

- Redgrave, Samuel (1878). A Dictionary of Artists of the English School. London: George Bell & Sons.

- Spender, Michael (1987). The glory of watercolour: the Royal Watercolour Society Diploma Collection. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8932-4. (registration required)

- Walpole, Josephine (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-85149-261-9.

- Wright, Christopher (2006). British and Irish Paintings in Public Collections. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11730-1.

Further reading

- "Joy, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15150. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Both brothers are included in the article.

- Cordingly, David (1974). Marine painting in England, 1700–1900. New York Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-289-70377-9.

- Stewart, Brian; Cutten, Mervyn (1987). Chichester artists. Canterbury, Kent: Bladen. ISBN 978-0-9512814-0-6.

External links

- Works by William Joy and John Cantiloe Joy in the Norfolk Museums Collections

- Works by John Cantiloe Joy and William Joy at Art UK

- Works by William Joy at the National Maritime Museum

- Works by the Norwich School of painters on the Mandell's Gallery website, including several by the Joy brothers

- Works by William Joy at the Yale Center for British Art

- Works by William Joy in the Royal Collection

- Works by William Joy sold at auction, as listed by Artnet

- Works by William Joy and John Cantiloe Joy at Invaluable

- Works by William Joy sold at Keys on 27 April 2018