John Crome

John Crome (22 December 1768 – 22 April 1821), once known as Old Crome to distinguish him from his artist son John Berney Crome, was an English landscape painter of the Romantic era, one of the principal artists and founding members of the Norwich School of painters. He lived in the English city of Norwich for all his life. Most of his works are of Norfolk landscapes.

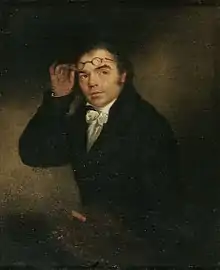

John Crome | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Michael William Sharp | |

| Born | John Crome 22 December 1768 Norwich, England |

| Died | 22 April 1821 (aged 52) Norwich |

| Nationality | English |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

| Spouse | Phoebe Berney |

| Children |

|

Crome's work is in the collections of public art galleries, including the Tate Gallery and the Royal Academy in London, and the Castle Museum in Norwich. He produced etchings and taught art.

Biography

John Crome was born on 22 December 1768 in Norwich,[2] and baptised on 25 December at St George's Church, Tombland, Norwich.[3] He was the son of John Crome, a weaver (who is also described as either an innkeeper or a lodger at a Norwich inn),[4] and his wife Elizabeth.[5] After a period working as an errand boy for a doctor (from the age of 12), he was apprenticed to Francis Whisler, a house, coach and sign painter.[6][note 1] At about this time he formed a friendship with Robert Ladbrooke, then an apprentice printer. They shared a room and went on sketching trips in the fields and lanes around Norwich.[2] They occasionally bought prints to copy.

Crome and Ladbrooke sold some of their work to a local printseller, Smith and Jaggars,[8] and it was probably through the print-seller that Crome met Thomas Harvey of Old Catton, who helped him set to up as a drawing teacher.[2] Crome had access to Harvey's art collection, which allowed him to develop his skills by copying the works of Thomas Gainsborough and Meindert Hobbema. Crome received further instruction and encouragement from the artist John Opie, and the English portraitist William Beechey, whose house in London he frequently visited.[9]

In October 1792 Crome married Phoebe Berney.[10] They produced two daughters and six sons, two of whom, John Berney Crome and William Henry Crome became landscape painters.[11]

In 1803 Crome and Ladbrooke formed the Norwich Society of Artists, a group that also included Robert Dixon, Charles Hodgson, Daniel Coppin, James Stark and George Vincent. Their first exhibition was in 1805; it marked the start of the Norwich School of painters, the first art movement created outside London.[12] Crome contributed 22 works to its first exhibition, held in 1805. He served as President of the Society several times and held the position at the time of his death.[13] With the exception of the times when he made short visits to London, he had little or no communication with the great artists of his own time.[9] He exhibited 13 works at the Royal Academy between 1806 and 1818. He visited Paris in 1814, following the defeat of Napoleon, and later exhibited views of Paris, Boulogne, and Ostend. Most of his subjects were of scenes in Norfolk.[13]

Crome was drawing master at Norwich School for many years. Several members of the Norwich School art movement were educated at the school and were taught by him,[14] including Stark and Edward Thomas Daniell.[15] He also taught privately, his pupils including members of the influential Gurney family, whom he stayed with whilst in the Lake District in 1802.[8]

.jpg.webp)

He died at his house in Gildengate, Norwich, on 22 April 1821, and was buried in St. George's Church. On his death-bed he is said to have gasped, "Oh Hobbema, my dear Hobbema, how I have loved you".[2] A memorial exhibition of more than 100 of his works was held in November that year by the Norwich Society of Artists.[8]

Crome's Broad and nearby Crome's Farm in The Broads National Park are named after him. The area surrounding Heartsease is covered by the Crome ward and division on Norwich City Council and Norfolk County Council respectively.

An incident in Crome's life was the subject of the one-act opera Twice in a Blue Moon by Phyllis Tate, to a libretto by Christopher Hassall: it was first performed in 1969. In the story Crome and his wife split one of his paintings in two to sell each half at the Norwich Fair.[16]

Works

Crome, who is sometimes referred to as "Old Crome",[17] worked in both watercolour and oil, producing more than 300 oil paintings during his career.

Between 1809 and 1813 he made a series of etchings. They were not published in his lifetime, although he issued a prospectus announcing his intention to do so.[18]

His two main influences are considered to be Dutch 17th-century painting and the work of the Welsh landscape painter Richard Wilson. Along with the artist John Constable, Crome was one of the earliest English painters to represent identifiable species of trees, rather than generalised forms.[9] His works, renowned for their originality and vision, were inspired by direct observation of the natural world combined with a comprehensive study of old masters.

The art historian Andrew Hemingway has identified a theme of leisure in Crome's work, citing particularly his works depicting the beach at Great Yarmouth, and the River Wensum in his native Norwich.[19] An example of the latter is the oil painting Boys Bathing on the River Wensum, Norwich, which was painted in 1817.[20] It depicts a scene at New Mills, the location of several of Crome's works.[21]

Gallery

_-_The_Poringland_Oak_-_N02674_-_National_Gallery.jpg.webp) The Poringland Oak (c.1818), National Gallery

The Poringland Oak (c.1818), National Gallery A Barge with a Wounded Soldier (undated), Yale Center for British Art

A Barge with a Wounded Soldier (undated), Yale Center for British Art The River Wensum, Norwich (c.1814), Yale Center for British Art

The River Wensum, Norwich (c.1814), Yale Center for British Art Yarmouth Jetty (c.1810), Yale Center for British Art

Yarmouth Jetty (c.1810), Yale Center for British Art Boys Bathing on the River Wensum, Norwich (1817), Yale Center for British Art

Boys Bathing on the River Wensum, Norwich (1817), Yale Center for British Art Woodland Landscape near Norwich (1810–1812), Yale Center for British Art

Woodland Landscape near Norwich (1810–1812), Yale Center for British Art_-_The_Bell_Inn_-_NG_2846_-_National_Galleries_of_Scotland.jpg.webp) The Bell Inn (c.1805), National Galleries of Scotland

The Bell Inn (c.1805), National Galleries of Scotland

Notes

- Cundall gives his master's name as 'Whistler'.[7]

References

- Clifford & Clifford1968, p. 28.

- Stephen 1888, pp. 140–143.

- Mottram 1931, p. 25.

- Binyon 1897, pp. 7–8.

- Mottram 1931, p. 30.

- Goldberg 1978, p. 38.

- Cundall 1920, p. 8.

- Cundall 1920, p. 9.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 483–484.

- Cundall 1920, p. 10.

- "William Henry Crome | 74 Artworks at Auction | MutualArt". www.mutualart.com. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- Walpole 1997, p. 19.

- Cundall 1920, p. 11.

- Cundall 1920, pp. 1, 17, 25, 26, 27, 31

- Cundall 1920, p. 32.

- Farnham Festival (1969). "Twice in a Blue Moon" (PDF). Phyllis Tate. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Cole & Van Dyke 1902, p. 141.

- Cundall 1920, p. 15.

- Hemingway 2016, p. 302.

- "Boys Bathing on the River Wensum, Norwich". Yale Center for British Art. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Hemingway 2016, p. 347.

Sources

- Binyon, Laurence (1897). John Crome and John Sell Cotman. London: Seeley & Co. OCLC 251906700.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Clifford, Derek; Clifford, Timothy (1968). John Crome. London: Faber and Faber Ltd. OCLC 557807587.

- Cole, Timothy; Van Dyke, John Charles (1902). Old English Masters. New York: The Century Co. OCLC 975407215.

- Cundall, Herbert Minton (1920). Holme, Geoffrey (ed.). The Norwich School. London: Geoffrey Holme Ltd. OCLC 651802612.

- Goldberg, Norman L. (1978). John Crome the Elder. Vol. 1: Text and a critical catalogue. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-1821-4.

- Hemingway, Andrew (2016). Landscape between Ideology and the Aesthetic: Marxist Essays on British Art and Art Theory, 1750–1850. Brill. p. 302. ISBN 978-90-04-26901-9.

- Mottram, Ralph Hale (1931). John Crome of Norwich. London: John Lane The Bodley Head Limited. OCLC 717763630.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 140–143.

- Walpole, Josephine (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Woodbridge, UK: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-85149-261-9.

Further reading

- Moore, Andrew W. (1985). The Norwich School of Artists. Norwich: HMSO/Norwich Museums Service. ISBN 978-0-11-701587-6.

- Theobald, Henry Studdy (1906). Crome's Etchings; a catalogue and an appreciation, with some account of his paintings. London: MacMillan and Co. Ltd. OCLC 250577003.

External links

- John Crome in "England Births and Christenings, 1538–1975", FamilySearch. (registration required)

- Artworks by or after John Crome at the Art UK site

- Works by (or relating to) John Crome at the British Museum

- Works by (or relating to) John Crome in the Norfolk Museums Collections

- Works by (or relating to) John Crome at the Yale Center for British Art