Fosterfields

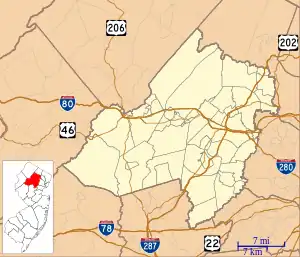

Fosterfields, also known as Fosterfields Living Historical Farm, is a 213.4-acre (86.4 ha) farm and open-air museum at the junction of Mendham and Kahdena Roads in Morris Township, New Jersey. The oldest structure on the farm, the Ogden House, was built in 1774.[5] Listed as the Joseph W. Revere House, Fosterfields was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 20, 1973, for its significance in art, architecture, literature, and military history.[6] The museum portrays farm life circa 1920.[7][8]

Fosterfields | |

Joseph W. Revere House | |

| |

| Location | Junction of Mendham and Kahdena Roads, Morris Township, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°48′6″N 74°30′16″W |

| Area | 213.4 acres (86.4 ha)[1] |

| Built | 1854 |

| Architect | Joseph Warren Revere |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival style |

| Part of | Washington Valley Historic District (ID92001583) |

| NRHP reference No. | 73001127[2] (original) 91000478[3] (increase) |

| NJRHP No. | 2175; 2176[4] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 20, 1973 |

| Boundary increase | October 9, 1991 |

| Designated CP | November 12, 1992 |

| Designated NJRHP | January 29, 1973 March 11, 1991 |

United States Navy officer, adventurer and author Joseph Warren Revere, a grandson of Paul Revere, was a significant owner of the property.[9] During Revere's ownership he designed and built an 1854 Carpenter-Gothic mansion titled "The Willows."[5][10][11]

In 1881 Charles Grant Foster, a New York commodities broker, purchased the property and developed it into a Jersey cattle farm entitled "Fosterfields." His daughter, Caroline Rose Foster, spent 98 years living and working on the property, enjoying carpentry, fishing, and civic engagement during the Gilded Age of Morristown.[9]

While writing her will in 1974, Caroline Foster arranged to bequeath the land to the Morris County Park Commission following her death, with the intent of making the property an educational farm.[12][13][14][15][8] Upon Foster's death in 1979, the Park Commission received the farm.[16][17] The boundary was increased on October 9, 1991.[18] It was listed as a contributing property of the Washington Valley Historic District on November 12, 1992.[19]

History

Lenape ownership

Around 1000 the land was inhabited by Munsee Lenape people. Circa 1500, Morris County was part of the Lenapehoking.[20] Arrowheads found in Munsee encampments throughout the Washington Valley suggest that they hunted wolf, elk, and wild turkey for game. They likely ate mussels from the Whippany River.[5]

In the 17th century Munsee fishermen made an annual pilgrimage from the Washington Valley to the Minisink Island on the Delaware River, in part to procure shellfish. Caroline Foster has said it is likely that Munsee farmers cultivated corn in the summertime in the fields of the Washington Valley.[5]

In 1757 colonists of the "New Jersey Association for Helping the Indians" forcibly relocated some 200 Lenape from the Washington Valley to Brotherton, New Jersey.[21] In 1801, some members of the tribe voluntarily traveled to join the Oneidas' reservation in Stockbridge, New York after receiving an invitation from the Oneidas.[22][9][23] However, colonists again expelled Lenape families in Stockbridge to Green Bay, Wisconsin in 1822.[9]

Ogden Farm

Circa the 1750s, Samuel Roberts had purchased over 150 acres (61 ha) of land in Washington Valley, including what became Fosterfields and the nearby Ranney farm. Caroline Foster has stated that Roberts enslaved three Black people; no further details are provided.[5]

In 1774, Samuel Roberts's stepson Jonathan Ogden married Abigail Gardiner.[5] That year, Roberts gave him 150 acres, presumably as a wedding gift.[24] Like his stepfather, Ogden enslaved three Black people.[5] A farmhouse was built to house Ogden, likely by carpenters he enslaved.[5]

The farmhouse is situated on the now-defunct Road to Jacob Arnold's. The road was named for Jacob Arnold's Tavern, a historically significant 1740s tavern then located at the Morristown Green.[25][6]

Although the farmhouse burned down in 1915, the original one-story foundation from 1774 still remains.[5]

In 1776, Ogden was listed as a landowner in Morristown. He was a county judge, and from 1802 to 1804, represented Morris County in New Jersey Legislature. He invested in the First Presbyterian Church's purchase of the Morristown Green.[5]

Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War winter of 1779–1780, General Washington stationed four regiments of artillery, field pieces, forges, and machine shops in nearby Burnham Park. Washington directed Henry Knox, Continental Brigadier general, to be in the proximity of the artillery park.[9] Knox either used the Ogden farmhouse or the Samuel Roberts house as his home and headquarters.[26]

Samuel Roberts and Jonathan Ogden fought in the American Revolutionary War.[9]

Slavery

Foster claims that Washington Valley households usually enslaved one person per twelve-person family.[5]

Circa 1825, Thomas, Neal, and Ibbe[5] were Black persons on the plantation enslaved by Jonathan Ogden. Ogden died in 1825 at the age of 82.[27] Jonathan Ogden put his wife Abigail and son Charles in charge of enforcing his will. In his will, Ogden stipulated "my wife Abigail have the time and services of my three blacks – Thomas, Neal, and Ibbe[Note 1] – during her life."[28] It is unclear whether Thomas, Neal, and/or Ibbe were freed after the death of Abigail Ogden. Sources do not indicate when the farm discontinued use of enslaved labor.[5]

Fire

On June 10, 1915, the Ogden house burned to the ground (except its 1774 foundation) due to a mattress being placed too close to a stove pipe. Foster recalled:

I woke up in the morning early and heard screams and shouts and I jumped up and you see the thing blazing...It took three days to burn, it was all solid oak ... I had [architect George Mills] draw a plan and I told him as near as I could how the thing looked.[29]

In 1915, the Ogden house was rebuilt based on Caroline Foster's memory of its appearance before the fire.[30][31]

Woods family

The historic Ogden house continued to be used as a residence, even after Revere built The Willows in 1854.[29]

From 1918 to 1927,[32] the historic Ogden house was occupied by the Woods family. Edward Woods (1875-1931) emigrated to the U.S. from Cornwall, England in 1909 and began working at Fosterfields in 1910, eventually being promoted to farm superintendent and moving into the Ogden House. Woods was paid a monthly salary of $95.[29]

His wife Agnes Woods (1879-1957) arrived in 1916 and was paid to provide food for the farmhands,[33] usually Irish immigrants,[34] at 25 cents a meal.[29] The house did not have running water during this time, requiring the Woods family to pump water into buckets and bring it up to the kitchen.[29]

The Woods family used a 1915 wood stove range to prepare family recipes, including biscuits with gravy[29] and pasties.[35][36][37] Due to their portability, Agnes Woods carried pasties to the farmhands working in the fields.[29] As of 2022, farm staff demonstrate the functional wood stove in educational cooking programs.[35][36][37]

The Willows

The Willows refers to a mansion commissioned by Joseph Warren Revere, completed in 1854.

Ogden farm purchase

A 1851 issue of The Jerseyman describes the estate, one year prior to its purchase by General Joseph Warren Revere:[38][39]

Very desirable farm known as the 'Ogden Farm,' lying about one mile west of Morristown upon the Morris turnpike and Eastern turnpike is offered for sale. Pleasantly situated with fine southern exposure and contains 88 acres (36 ha) of land. There is upon it an excellent two-storey dwelling house with kitchen attached; good barn, cow house, wagon house, and other outbuildings; never failing spring run of water passing near the house and through lawn; wood land. Title indisputable.

In 1852, Revere purchased the Ogden Farm from then-landowner Platt Rogers for $6,000.[38] Revere was a naval officer. He is the grandson of Paul Revere who was best known for his role in the American Revolutionary War.[38] His other travels (usually related to wars) took him to Mexico, Cuba, Liberia, France, Germany, Greece, Egypt, Portugal, Spain, Algeria, and Italy. Revere chose to settle in New Jersey.[40][41]

Construction

Revere planned to construct a new, customized mansion. It would later be known as The Willows, due to the large grove of willows in the woods surrounding the property.[5]

Revere chose a site about 700 feet (210 m) west of the Ogden house, upon a picturesque slope overlooking the farm. He contracted local master carpenter Ashbel Bruen of Chatham to construct the home.[10][11] It has deeply pitched crossing gabled roofs and its front door faces southeast.[38]

The design of The Willows resembles Gevase Wheeler's 1849 Olmstead House. In his pattern book Rural Homes of 1851, British architect Gervase Wheeler published his pattern for Henry Olmstead's then-$3,000 house "about a mile and a half" from East Hartford, Connecticut.[38][42] Historian Renée Elizabeth Tribert argues that either Revere or Bruen undoubtedly owned a copy of the book and based it on Wheeler's design.[43] The end result reflected Gothic Revival style – specifically, Carpenter Gothic.[6] Revere hoped to retire on the estate.[6]

While Bruen constructed the Willows from 1852 to 1854, the Revere family temporarily lived in the Ogden house. During this time, Thomas Duncan Revere was born, on November 22, 1853.[10]

Written on August 7, 1854, Bruen's construction contract stated:[10]

[Bruen] shall and will on or before the first day of February erect, build, setup, and finish one dwelling house [for $7,125.15].

Bruen's construction of The Willows was completed in 1854, when the Reveres moved in.[6][10] Norway spruces were planted around the mansion.[5]

A self-taught artist, Revere likely painted the elaborate tromp l'oeil murals in the dining room, which were later maintained by the Foster family. The dining room murals include still lives, the Revere family crest, and a bouquet of baguettes. Revere also painted what appear to be wooden Gothic arches onto many of the walls.[6][44]

In 1861, the Civil War prompted Revere to voluntarily join the Union military. Revere became Union Army General; he was commander of the 7th New Jersey Infantry Regiment and 2nd New Jersey Infantry Regiment. In 1872, injuries forced Revere to move to Morristown.[45]

A January 9, 1873 letter from President Grant's secretary is addressed to Revere at "The Rancho," suggesting this was another nickname of The Willows.[46]

Tenants

From 1872 to 1881, the Reveres rented The Willows out to tenants. Among these tenants was fiction author Bret Harte.[18] Harte drew inspiration from his time in Morristown to write 1877 novel Thankful Blossom, a regionalist historical romance that takes place in Morristown.[47]

On April 20, 1880, Revere died of a heart attack[5] while on a ferry to New York.[48]

Fosters' ownership

From 1878 to 1880, Brooklyn Heights-based commodity broker Charles Grant Foster (1843–1927) rented The Willows, possibly to provide his wife with medical care for tuberculosis.[49] In 1881, following Revere's death, Charles Foster purchased the entire property.[33][50]

In 1882, Foster purchased two adjoining farms: the Gribbon Farm on the east and the Nathaniel Wilson Farm on the west.[5] He managed the farm while continuing to work in New York City and Morristown. Foster can be considered a gentleman farmer.[51] His family lived and entertained guests in The Willows, Revere's former estate.[33]

In 1882, to establish his dairy farm, Foster and his brother began imported purebred Jersey cows from the British Isle of Jersey, the largest of the Channel Islands. By 1883, the herd numbered around 70 head of cattle.[29]

Foster invested in progressive farming technologies of his time. In 1883, he build an ensilage pit to feed cows during the winter, which demonstrated his investment in modern ideas. Other technology included kerosene-powered egg incubation, crop rotation, and steam-engine fodder choppers and water pumps (replaced by gasoline engine in 1915).[29]

In 1884, Caroline Foster was brought to the Isle; she later recalled, "We traveled from one village to another in horse and buggy, buying one cow here and one cow there." By 1884, the Fosters' herd had about 100 head.[29]

Circa 1900, Foster affixed a wooden plain-front wall telephone to the hall of The Willows. Presumably, this investment allowed him to keep in contact with his office in New York.[29]

Charles Foster participated in the American Jersey cattle trading industry, as evident by journal advertisements. Foster's herd was registered with The American Jersey Cattle Club; he traded with breeders Jeremiah Roth of Allentown, Pennsylvania; John T. Foote of Springbrook Farm, Morristown; and Louis Gillespie of Tower Hill (now Villa Walsh), Morristown.[29] An August 1900 advertisement in The Country Gentleman reads:[52]

FOSTERFIELD'S HERD JERSEYS.

FOR SALE—COWS and HEIFERS, all my own breeding, and a choice lot in every way. Nearly every one sired by bulls...with butter tests of 14 lb. and upward, and served by bulls of the same standard. Will sell singly or a carload. Also for Sale, Bulls out of Tested Cows. Address

CHARLES G. FOSTER

Post-Office Box 173, Morristown, Morris Co., N.J.

A similar September 1919 advertisement was posted in Home and Field Illustrated:[53]

Fosterfield's Herd Registered Jerseys.

FOR SALE—Young Cows. Heifers, due to be fresh this summer and later.

Calves, both sexes, very attractive.

Come and see them or write

CHARLES G. FOSTER

P. O. Box 173, Morristown, Morris Co., N.J.

Foster maintained a daily farm journal for 40 years.[50] Foster employed farmhands and coachmen to work on the property. An example of Foster's employees were the Woods family, English immigrants from Cornwall; more details are provided above.[33] Andrew Gibbons, the Irish coachman, is another employee of the Foster's; a reenactor portrayed Gibbons in a 2017 Irish history event.[34]

Temple of Abiding Peace

In 1916, Caroline Foster began to build a one-room Cape Cod-style cottage outside The Willows.[54] She was skilled in carpentry and hoped to complete the house's construction independently.[55] In 1919, she completed the cottage and named it "The Temple of Abiding Peace." Biographer Becky Hoskins claims it was a "refuge from the daily stresses of her life," which included daily supervision of the farm and her father losing his hearing.[29] Likely named in response to the Great War,[29] the Temple of Abiding Peace was used as a workshop to entertain guests and craft birdhouses with friends.[56] She planted a garden around the house,[57][58] which continues to be maintained.[59]

Historic landscape consultant Marta McDowell claims Foster's garden is significant because "it displays features that span the history of 19th- and 20th-century American gardening: the Romantic era of the early 1800s, the Colonial Revival of 1876 onwards, and the imported English perennial borders of the early 20th century."[29]

In 1925, due to Charles Foster's failing health, most of the herd of Jersey cattle were sold in an auction. In 1927, Charles Foster died, and his 50-year-old daughter Caroline Foster took charge of the farm. She continued to sell milk, eggs, butter, vegetables, and honey to local customers and friends. In 1928, Caroline Foster bought a gasoline-powered tractor; this was a technological advancement replacing Charles Foster's method of draft horses.[29] Despite embracing new farm machinery, Charles Foster was opposed to automobiles, referring to Foster's Model T Ford as a "damn contraption."[29]

In 1999, the Temple of Abiding Peace opened to the public as part of the open-air museum.[29]

In 1937, Caroline Foster electrified The Willows and the Ogden farmhouse.[29] In 1967, at the age of 90 and beyond, Caroline Foster continued to watch farm workers thresh wheat and plant crops.[29]

Museum

Fosterfields is the first of New Jersey's three living historical farms.[60]

In 1974 farmer and philanthropist Caroline Rose Foster (1877–1979) bequeathed her estate to the Morris County Park Commission to preserve the farm.[18][61][62] In her will, Foster stipulated:[63]

I give, devise and bequeath to the COUNTY OF MORRIS, in fee simple, for the use by the Morris County Park Commission, my farm in Morris Township, Morris County, New Jersey, on both sides of the road leading from Morristown to Mendham, intending to include all of my real estate in Morris Township. It is my desire that the use made of the property and its development by the County be kept as simple as possible, and that the natural condition of the property be maintained to the extent possible so that the wildlife and trees and flowers on the property may be protected and preserved for the education and pleasure of the public. It is my further wish that the use be educational and historical rather than recreational, and that there be no food or amusement concessions. I suggest, if it seems desirable, that this property be maintained as a farm.

Farm open-air museum

The property is an open-air museum demonstrating farm chores in the early 20th century.[17] Pamphlets of the museum state that it specifically focuses on Fosterfields during the 1880s to 1930s. It specifically depicts the Fosters' life in The Willows and the Woods family's life in the Ogden House.[7] Antique machinery is on display and part of demonstrations, including early 20th century steam engines, corn sheller, icebox, wood stove, and barrel butter churns.[64][65]

Visitors can see farm animals, farmers plowing and planting fields, and historical tour guides. Guests may help perform daily farm tasks like collecting eggs, cleaning the horse harness, and grinding feed corn for the chickens.[1]

As of 2022, heritage breeds at the farm include:[66]

- Jersey cattle;

- Buff Orpington, Rhode Island Red, Plymouth Barredrock, and White Leghorn chickens;

- Oberhasli goats;

- Cayuga ducks;

- African goose;

- Shropshire rams, and mixed Leicester/Romney ewes.

The farm has hosted sheepdog trials since the late 1980s. In 2005, the trials were discontinued, but returned in 2014.[67][68][69]

Circa 2004, the farm offered a "Share-a-Chore" program, where members of the public would pay admission to do farm chores like cleaning stalls and maintaining equipment. It also ran a program called "Spread It Around" where paying observers watched a team of Belgian workhorses scatter manure on a pasture.[70]

In 2010, Connolly & Hickey Historic Architects conducted a historic structures report, then repaired and restored the barnyard complex at Fosterfields.[71]

In 2011, the farm offered a series of classes called "The Wood Stove Cook" to teach members of the public how to cook on an antique wood stove.[61]

On August 3, 2019, Fosterfields hosted Model T Ford day to celebrate the popular automobile. Festivities included displaying Caroline Foster's Model T Ford, gifted to her by her friends, and celebrating the history of motor vehicles. Historians instructed guests on how to crank and drive antique cars, and car collectors were invited to display their Model Ts.[72]

In 2019, the Fosterfields Farm Harvest festival included wagon rides, butter churning, apple cider pressing, live music, "old-time dancing," and farm animals.[73]

On February 13, 2022, Fosterfields hosted "Winter's Day," wherein guests were invited to experience ice cutting, maple tree tapping, wood sawing, wagon rides, petting cows, and an outdoor cooking demonstration.[74]

In May 2021 and May 2022, Fosterfields hosted an educational sheep-shearing and wool event titled "Born to be Shorn." Throughout the event, guest expert shearer Margaret Quinn[75] demonstrated sheep shearing with blade shears.[76][77]

Transportation exhibit

In her will, Caroline Foster stipulated:[29]

It is contemplated that the Commission will erect a fire resistant building on a part of the farm which I have already deeded to it. This will be a museum for the purpose of housing and displaying a transportation exhibit, including my collection of carriages, wagons, sleighs, harness, antique automobile, farm equipment and other articles.

As requested, her automobiles are displayed in the Fosterfields Visitors Center near the entrance, in a museum exhibit titled "Driving Into the Twentieth Century." Guests can view her 1922 Model T Ford and a 1929 Hupmobile along with two hands-on vehicular activities.[29] However, Foster's horse-drawn carriages are displayed in the Carriage House located beside the barn on the main farm.[29]

Accessibility

In 2022, photography club students at the County College of Morris created a virtual reality exhibit of the Willows' second floor, led by Professor Nicole Schwartz. The students were taught to combine 3D modeling with 360-degree cameras and photo stitching; Schwartz explains, "Every 360 shot is a collage of six individual images that students worked diligently to stitch together." The goal was to provide a second-floor experience for people with mobility disabilities; the upper level of the Willows is not wheelchair accessible due to an 18-step historically narrow staircase and lack of elevator access. This exhibit claims to provide an accessible experience for "history buffs facing mobility issues."[78]

Gallery

Information sign

Information sign The barn at Fosterfields

The barn at Fosterfields

See also

- Acorn Hall, a nearby Morristown historic house museum donated by Mary Crane Hone in 1971

- Washington Valley Historic District

- Indian Mills, New Jersey

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Morris County, New Jersey

- Howell Living History Farm

- Longstreet Farm

- History of slavery in New Jersey

Notes

- The will was handwritten in a mix of Palmer and Spencerian scripts. The letters appear to spell Ibbe. Unofficial sources suggest this name is of Latin and Biblical origin (Iacobus).

References

- "Fosterfields Living Historical Farm". Morris County Park Commission. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- "National Register Information System – (#73001127)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- "National Register Information System – (#91000478)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places – Morris County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection – Historic Preservation Office. December 28, 2020. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Barbara, Hoskins; Foster, Caroline; Roberts, Dorothea; Foster, Gladys (1960). Washington Valley, an informal history. Edward Brothers, Inc. OCLC 28817174.

- Gamble, Robert S.; Kerschner, Terry (July 19, 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Joseph W. Revere House". National Park Service. With accompanying 2 photos

- Press, Independent (August 26, 2012). "Tour The Willows in Morristown". nj. Archived from the original on March 25, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Fosterfields Living Historical Farm | Morris County Parks". www.morrisparks.net. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Barbara, Hoskins; Foster, Caroline; Roberts, Dorothea; Foster, Gladys (1960). Washington Valley, an informal history. Edward Brothers. OCLC 28817174.

- Chemerka, WIlliam R. General Joseph Warren Revere: The Gothic Saga of Paul Revere's Grandson. BearManor Media. p. 88. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Emblen, M. l (June 3, 1990). "NEW JERSEY GUIDE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- Barbato, Joan (May 5, 1989). "Restoration of "Willows" completed, B1". Daily Record. Morristown, New Jersey. pp. B1. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- Barbato, Joan (May 5, 1989). "Restoration of "Willows" complete, B4". Daily Record. Morristown, New Jersey. pp. B4. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- Friends of Fosterfields: The Farm Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Press, Independent (August 26, 2012). "Tour The Willows in Morristown". nj. Archived from the original on March 25, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- Nadzeika, Bonnie-Lynn (2012). Morristown. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9280-0. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- "Fosterfields". www.usgenwebsites.org. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Strathearn, Nancy (August 16, 1990). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Fosterfields (Boundary Increase)". National Park Service. With accompanying 28 photos

- Foster, Janet W. (November 12, 1992). "NRHP Nomination: Washington Valley Historic District". National Park Service.

- "NRHP Nomination: Washington Valley Historic District (56 photos)". National Park Service. 1991.

- Alvin M. Josephy Jr, ed. (1961). The American Heritage Book of Indians. American Heritage. pp. 168–189. LCCN 61-14871.

- "Collection: New Jersey Association for helping the Indians records | Archives & Manuscripts". archives.tricolib.brynmawr.edu. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "The Brotherton Indians of New Jersey, 1780 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- "New Stockbridge Tribe". collections.dartmouth.edu. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Vermilye, Anna S. (1906). Ogden Family History in the Line of Lieutenant Benjamin Ogden of New York: (born June 22, 1735-died August 16, 1780) of the Prince of Wales' American Regiment, and His Wife Rachel Westervelt, with Some Account of His Ancestry and Descendants. Orange Chronicle Company, printers. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- "Road past Farmhouse - Print, Photographic | Morris County Park Commission". morrisparks.pastperfectonline.com. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- Smith, Samuel Stelle (1979). Winter at Morristown, 1779–1780: The Darkest Hour. Philip Freneau Press. ISBN 978-0-912480-15-2. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Chemerka, WIlliam R. General Joseph Warren Revere: The Gothic Saga of Paul Revere's Grandson. BearManor Media. p. 18. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Last will and testament of Jonathan Ogden, notarized by Jeremiah M. De'Camp, surrogate of the County of Morris, 1848. Document available in Morris County Park Commissions archive.

- Hoskins, Rebecca (2010). Caroline Foster and Fosterfields Living Historical Farm : a life and a legacy. Ralph Iacobelli, Morris County Park Commission. Morristown, N.J.: The Friends of Fosterfields Living Historical Farm and Cooper Gristmill. ISBN 978-0-615-39122-9. OCLC 709909049.

- "Paranormal Event at Morristown's Fosterfields". TAPinto. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- michellelongo (November 15, 2019). "Weekend Family Fun: Service Dogs, Story Times, Dance and More". Baristanet. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Edward Woods, farmer at Fosterfields 1981-1927. – Negative | Morris County Park Commission". morrisparks.pastperfectonline.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Ash, Lorraine. "Fosterfields teaches kids about old-school farming". Daily Record. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Celebrate Irish History at Fosterfields Living Historic Farm in Morristown; Saturday April 22". TAPinto. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Gorce, Tammy La (March 12, 2011). "Grandma's Recipes, Made With Her Tools". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Enjoy a country Christmas at Fosterfields in Morris Township in December". New Jersey Hills. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Enjoy a wagon Ride at Historic Holidays – Morristown, NJ". www.americantowns.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Chemerka, WIlliam R. General Joseph Warren Revere: The Gothic Saga of Paul Revere's Grandson. BearManor Media. p. 87. Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Hoskins, Barbara (1960). Washington Valley: An Informal History, Morris County, New Jersey. Edwards Brothers. p. 207. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Revere, Joseph Warren (1872). Keel and Saddle: A Retrospect of Forty Years of Military and Naval Service. J.R. Osgood. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Revere, Joseph Warren (September 2009). Keel and Saddle. Applewood Books. ISBN 978-1-4290-2160-9. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Guter, Robert P. The Willows at Fosterfields Historic Structure Report, "Architectural History Report", 1983. Written by Robert P. Guter of Acroterion Historic Preservation Consultants, available in the archives of the Morris County Park Commission.

- Tribert, Renée Elizabeth (1988). "Gervase Wheeler: Mid-Nineteenth Century British Architect in America". p. 13 (iii). Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- Chemerka, WIlliam R. General Joseph Warren Revere: The Gothic Saga of Paul Revere's Grandson. BearManor Media. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- "Map of Fosterfields". The Friends of Fosterfields and Cooper Mill. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Letter from the Executive Mansion. "FOSTERFIELDS ARCHIVES\Revere Archives\Revere Box 1\Letter January 9th, 1873." January ninth, 1873 – via Fosterfields Collections, Morris County Park Commission.

- "The Project Gutenberg E-text of Thankful Blossom, by Bret Harte". www.gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- Chemerka, WIlliam R. General Joseph Warren Revere: The Gothic Saga of Paul Revere's Grandson. BearManor Media. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Morris County Park Commission. "Foster Family Papers". PastPerfectOnline. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- "Farm, History – Fosterfields Living Historical Farm – The Willows – Are We There Yet?". www.fieldtrip.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Fosterfields Living Historical Farm ⋆ Your Next Destination Awaits – Morris County, NJ". Your Next Destination Awaits – Morris County, NJ. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- The Country Gentleman. Luther Tucker & Son. 1900. p. 637. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- Home and Field Illustrated. Field Publications, Incorporated. September 1919. p. 745. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- New Jersey Women's Heritage Trail. New Jersey Historic Preservation Office. 2004.

- "Caroline Foster · The Legacy of Women of Morris County · North Jersey History Center Online Exhibits". womc.omeka.net. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- "Learn About Cara's Cottage Saturday". Morris Township-Morris Plains, NJ Patch. September 2, 2011. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- "Kitchen Table Kibitzing 5/12/2015: The Temple of Abiding Peace". Daily Kos. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- "Fosterfields Cottage Watercolor, by Hattie Evans – Painting | Morris County Park Commission". morrisparks.pastperfectonline.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- LOOSE, RUSE ON THE. "Friends help Fosterfields celebrate anniversary". Daily Record. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Jacobs, Muriel (September 14, 1986). "Antiques; Learning About Victorian Houses". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- La Gorce, Tammy (March 12, 2011). "Grandma's Recipes, Made With Her Tools". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- La Gorce, Tammy (June 5, 2010). "Plenty of Reasons to Leave the House". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Will of Caroline R. Foster, provided by the Morris County Park Commission documents.

- "Fosterfields Living Historical Farm". Festhund. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- Sovelove, Jeff. "A balmy winter day on the farm in Morris Township". Morristown Green. Archived from the original on February 5, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Denville Community News and Events | DenvilleCommunity A Virtual Downtown | Page 15". Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- "Sheep Dog Trials in Morristown". Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- "BY THE WAY; the Bark of the Players". The New York Times. August 27, 2000. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- "Sheep herding dogs back at Fosterfields in June". Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- Gorce, Tammy La (August 8, 2004). "BY THE WAY; What I Shoveled Last Summer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- "Fosterfields Living Historical Farm – Restoration of the Barnyard Complex in Morris Township, NJ". Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- "Model T Ford Day at Fosterfields Living Historical Farm on Saturday, August 3". www.morriscountynj.gov. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- NJ.com, Amy Kuperinsky | NJ Advance Media for (September 11, 2019). "New Jersey fall festivals 2019: See our huge statewide events guide". nj. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- "Don't Miss the Winter Fun & Events at Morris County Parks". www.morriscountynj.gov. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- Sovelove, Jeff. "'Born to be Shorn': Sheepish haircuts at Fosterfields in Morris Township". Morristown Green. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- michellelongo (May 13, 2022). "Weekend Family Fun: Mayfair Celebration, Anderson Park Olmsted Party, Hula and More". Baristanet. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- "Morristown Happenings: Things to Do in and Around Morristown This Weekend; May 13 - May 15". TAPinto. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- Myers, Gene. "Virtual reality unlocks historic North Jersey mansion for people with disabilities". North Jersey Media Group. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

External links

- "Visit Fosterfields". The Friends of Fosterfields and Cooper Mill.

- "Fosterfields". Morris Township, NJ – Official Website.

- "Fosterfields – 1854". Historical Marker Database.

- "Fosterfields Living Historical Farm". Historical Marker Database.

- The second-floor experience (hosted on the County College of Morris website)

![]() Media related to Fosterfields at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fosterfields at Wikimedia Commons