Judeo-Aramaic languages

Judaeo-Aramaic languages represent a group of Hebrew-influenced Aramaic and Neo-Aramaic languages.[1]

Early use

Aramaic, like Hebrew, is a Northwest Semitic language, and the two share many features. From the 7th century BCE, Aramaic became the lingua franca of the Middle East. It became the language of diplomacy and trade, but it was not yet used by ordinary Hebrews. As described in 2 Kings 18:26, the messengers of Hezekiah, king of Judah, demand to negotiate with ambassadors in Aramaic rather than Hebrew (yehudit, literally "Judean" or "Judahite") so that the common people would not understand.

Gradual adoption

During the 6th century BCE, the Babylonian captivity brought the working language of Mesopotamia much more into the daily life of ordinary Jews. Around 500 BCE, Darius I of Persia proclaimed that Aramaic would be the official language for the western half of his empire, and the Eastern Aramaic dialect of Babylon became the official standard.[2] In 1955, Richard Frye questioned the classification of Imperial Aramaic as an "official language", noting that no surviving edict expressly and unambiguously accorded that status to any particular language.[3]

Documentary evidence shows the gradual shift from Hebrew to Aramaic:

- Hebrew is used as first language and in society; other similar Canaanite languages are known and understood.

- Aramaic is used in international diplomacy and foreign trade.

- Aramaic is used for communication between subjects and in the imperial administration.

- Aramaic gradually becomes the language of outer life (in the marketplace, for example).

- Aramaic gradually replaces Hebrew in the home, and the latter is used only in religious activity.

The phases took place over a protracted period, and the rate of change varied depending on the place and social class in question: the use of one or other language was probably a social, political, and religious barometer.

From Greek conquest to Diaspora

The conquest of the Middle East by Alexander the Great in the years from 331 BCE overturned centuries of Mesopotamian dominance and led to the ascendancy of Greek, which became the dominant language throughout the Seleucid Empire, but significant pockets of Aramaic-speaking resistance continued.

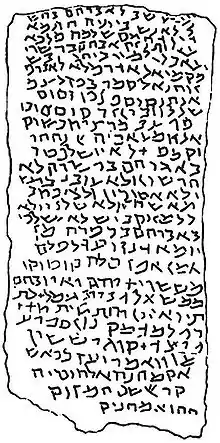

Judaea was one of the areas in which Aramaic remained dominant, and its use continued among Babylonian Jews as well. The destruction of Persian power, and its replacement with Greek rule helped the final decline of Hebrew to the margins of Jewish society. Writings from the Seleucid and Hasmonaean periods show the complete supersession of Aramaic as the language of the Jewish people. In contrast, Hebrew was the holy tongue. The early witness to the period of change is the Biblical Aramaic of the books of Daniel and Ezra. The language shows a number of Hebrew features have been taken into Jewish Aramaic: the letter He is often used instead of Aleph to mark a word-final long a vowel and the prefix of the causative verbal stem, and the masculine plural -īm often replaces -īn.

Different strata of Aramaic began to appear during the Hasmonaean period, and legal, religious, and personal documents show different shades of hebraism and colloquialism. The dialect of Babylon, the basis for Standard Aramaic under the Persians, continued to be regarded as normative, and the writings of Jews in the east were held in higher regard because of it. The division between western and eastern dialects of Aramaic is clear among different Jewish communities. Targumim, translations of the Jewish scriptures into Aramaic, became more important since the general population ceased to understand the original. Perhaps beginning as simple interpretive retellings, gradually 'official' standard Targums were written and promulgated, notably Targum Onkelos and Targum Jonathan: they were originally in a Palestinian dialect but were to some extent normalised to follow Babylonian usage. Eventually, the Targums became standard in Judaea and Galilee also. Liturgical Aramaic, as used in the Kaddish and a few other prayers, was a mixed dialect, to some extent influenced by Biblical Aramaic and the Targums. Among religious scholars, Hebrew continued to be understood, but Aramaic appeared in even the most sectarian of writings. Aramaic was used extensively in the writings of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and to some extent in the Mishnah and the Tosefta alongside Hebrew.

Diaspora

The First Jewish–Roman War of 70 CE and Bar Kokhba revolt of 135, with their severe Roman reprisals, led to the breakup of much of Jewish society and religious life. However, the Jewish schools of Babylon continued to flourish, and in the west, the rabbis settled in Galilee to continue their study. Jewish Aramaic had become quite distinct from the official Aramaic of the Persian Empire by this period. Middle Babylonian Aramaic was the dominant dialect, and it is the basis of the Babylonian Talmud. Middle Galilean Aramaic, once a colloquial northern dialect, influenced the writings in the west. Most importantly, it was the Galilean dialect of Aramaic that was most probably the first language of the Masoretes, who composed signs to aid in the pronunciation of scripture, Hebrew as well as Aramaic. Thus, the standard vowel marks that accompany pointed versions of the Tanakh may be more representative of the pronunciation of Middle Galilean Aramaic than of the Hebrew of earlier periods.

As the Jewish diaspora was spread more thinly, Aramaic began to give way to other languages as the first language of widespread Jewish communities. Like Hebrew before it, Aramaic eventually became the language of religious scholars. The 13th-century Zohar, published in Spain, and the popular 16th-century Passover song Chad Gadya, published in Bohemia, testify to the continued importance of the language of the Talmud long after it had ceased to be the language of the people.

20th century

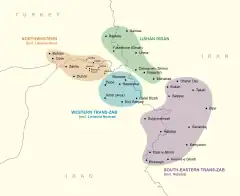

Aramaic continued to be the first language of the Jewish communities that remained in Aramaic-speaking areas throughout Mesopotamia. At the beginning of the 20th century, dozens of small Aramaic-speaking Jewish communities were scattered over a wide area extending between Lake Urmia and the Plain of Mosul, and as far east as Sanandaj. Throughout the same region l, there were also many Aramaic-speaking Christian populations. In some places, Zakho for instance, the Jewish and Christian communities easily understood each other's Aramaic. In others, like Sanandaj, Jews and Christians who spoke different forms of Aramaic could not understand each other. Among the different Jewish dialects, mutual comprehension became quite sporadic.

In the middle of the 20th century, the founding of the State of Israel led to the disruption of centuries-old Aramaic-speaking communities. Today, most first-language speakers of Jewish Aramaic live in Israel, but their distinct languages are gradually being replaced by Modern Hebrew.

Modern dialects

Modern Jewish Aramaic languages are still known by their geographical location before the return to Israel.

These include:

- Lishana Deni – originally spoken in Kurdistan Region of Northern Iraq and Southeastern Turkey

- Lishan Didan – originally spoken in Iranian Azerbaijan and Lake Van area in Turkey

- Lishanid Noshan – originally spoken in northeastern Iraq in the region of Arbil

- Hulaulá – originally spoken in Iranian Kurdistan

- Barzani Jewish Neo-Aramaic – or Lishanid d'Janan – originally spoken in three villages near Aqrah in Iraq

- Betanure Jewish Neo-Aramaic – or Lishan Huddaye originally from the village Bar Tanura in Iraq

Judeo-Aramaic studies

Judeo-Aramaic studies are well established as a distinctive interdisciplinary field of collaboration between Jewish studies and Aramaic studies. The full scope of Judeo-Aramaic studies includes not only linguistic, but rather the entire cultural heritage of Aramaic-speaking Jewish communities, both historical and modern.[4]

Some scholars, who are not experts in Jewish or Aramean studies, tend to overlook the importance of Judeo-Aramaic cultural heritage.

See also

References

- Beyer 1986.

- F. Rosenthal; J. C. Greenfield; S. Shaked (December 15, 1986), "Aramaic", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Iranica Online

- Frye, Richard N.; Driver, G. R. (1955). "Review of G. R. Driver's "Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B. C."". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 18 (3/4): 456–461. doi:10.2307/2718444. JSTOR 2718444. p. 457.

- Morgenstern 2011.

Sources

- Beyer, Klaus (1986). The Aramaic Language: Its Distribution and Subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783525535738.

- Gzella, Holger (2015). A Cultural History of Aramaic: From the Beginnings to the Advent of Islam. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004285101.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2008). The Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Urmi. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-59333-425-3.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2009). The Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Sanandaj. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-60724-134-8.

- Morgenstern, Matthew (2011). Studies in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: Based Upon Early Eastern Manuscripts. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9789004370128.

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2): 5–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-28.

- Sabar, Yona (2002). A Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dictionary: Dialects of Amidya, Dihok, Nerwa and Zakho, Northwestern Iraq. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447045575.

- Sokoloff, Michael (1990). A Dictionary of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic of the Byzantine Period. Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press. ISBN 9789652261014.

- Sokoloff, Michael (2002). A Dictionary of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic of the Talmudic and Geonic Periods. Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press. ISBN 9780801872334.

- Sokoloff, Michael (2003). A Dictionary of Judean Aramaic. Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press. ISBN 9789652262615.

- Sokoloff, Michael (2012a). "Jewish Palestinian Aramaic". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 610–619. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Sokoloff, Michael (2012b). "Jewish Babylonian Aramaic". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 660–670. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Sokoloff, Michael (2014). A dictionary of Christian Palestinian Aramaic. Leuven: Peeters. OCLC 894312905.

- Stevenson, William B. (1924). Grammar of Palestinian Jewish Aramaic. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9781725206175.