Mines of Spain State Recreation Area and E. B. Lyons Nature Center

The Mines of Spain State Recreation Area and E. B. Lyons Nature Center is a state park in Dubuque County, Iowa, United States. It is near Dubuque, the eleventh-largest city in the state. The park features picnic areas, 15 miles (24 km) of walking/hiking trails, 4 miles (6.4 km) of ski trails, and the Betty Hauptli Bird and Butterfly Garden. It also includes archaeological sites of national importance as an early lead mining and smelting venture led by French explorer Julien Dubuque, as well as Dubuque's gravesite. These sites were collectively designated a National Historic Landmark District as Julien Dubuque's Mines.

| Mines of Spain State Recreation Area and E. B. Lyons Nature Center | |

|---|---|

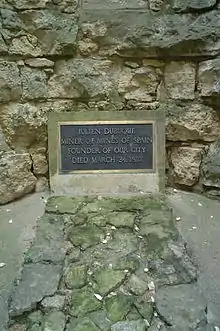

Julien Dubuque's monument | |

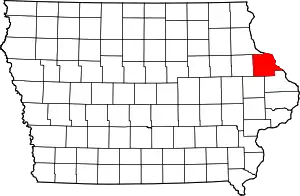

Location of Mines of Spain State Recreation Area and E. B. Lyons Nature Center in Iowa | |

| Location | Dubuque, Iowa, United States |

| Coordinates | 42°27′45″N 90°39′45″W |

| Area | 1,380 acres (5.6 km2) |

| Elevation | 751 ft (229 m)[1] |

| Established | 1981 |

| Named for | Julien Dubuque's Mines |

| Governing body | Iowa Department of Natural Resources |

Julien Dubuque's Mines | |

| Built | 1897 |

| Architect | Alexander Simplot; Carter Bros. |

| Architectural style | Late Gothic Revival |

| MPS | Mines of Spain Archeological MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 88002662 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 21, 1988[2] |

| Designated NHLD | November 04, 1993[3] |

History

Prehistoric settlement

The earliest known inhabitants of this area were from the Late Archaic period (2,050 BCE to 450 BCE).[4] This era is marked by an increasing sense of regionalism and sedentary occupation of land. The existence of copper in northeast Iowa from the Lake Superior region suggests the practice of long-distance trade. Archaeologists have located evidence of a wide variety of projectile points from this era, population expansion, exchange of raw materials and finished goods, and galena, which is associated with more complex mortuary rituals. Evidence from the Woodland period (450 BCE to 1250 CE) are found in pottery, burial mounds, and cultivated plants. Locally, this period of settlement grew out of the Late Archaic period, which in turn transitioned into the Oneota period (950 CE to European contact).[4] The Oneota are an Upper Mississippian culture that is marked by subsistence on horticulture as in the past, but increasingly on hunting and gathering. Elements from this era include bison and scapula hoes, triangular projectile points, and manos and metates.

Meskwaki

The Meskwaki tribe is believed to have arrived in this area as early as the 1760s, but were definitely in place by the 1780s.[4] The tribe lived in the lower peninsula of Michigan and possibly in Ohio before 1640 when the Iroquois forced them to the region around Green Bay in Wisconsin. As a result of the Fox Wars with the French ending in 1737 and the relocation of the Ojibwa in 1773, they were then pushed to the south and west. The Meskwaki's subsistence was primarily based on horticulture and hunting and supplemented with fishing and gathering wild foods. That started to slowly change as they became involved as middle men in the fur trade by the late 1600s. The tribe lived in semi-permanent palisaded villages of pole-frame lodges. Seasonally, family groups occupied smaller villages for hunting and other subsistence purposes. Their villages were generally located near the bank of navigable waterways. Meskwaki involvement with the lead trade began as a supplement to the fur trade and it was a source of trade goods for the tribe. Only a small portion of the tribe was involved and the work was carried out by the women and older men.[4] They only mined the surface deposits, and then they smelted the ore using two kinds of temporary smelting furnaces. They would transport the lead to nearby traders and occasionally brought the ore to St. Louis themselves to trade.

Julien Dubuque's Mines

Julien Dubuque entered an agreement with the Meskwaki in 1788 to mine lead. He is believed to be the first European to settle on what is now Iowa.[5] The Governor of New Spain gave Dubuque a grant to work Spanish-owned land, naming the 1,380-acre (560 ha) area The Mines of Spain. Dubuque developed a trading post near the Meskawki village (Village of Kettle Chief) along Catfish Creek. It included his residence, houses for Euro-American or employees of mixed origin, a grain mill, storage cellar for furs, one or two barns, a blacksmith shop, and several other storage facilities. The surrounding land was also farmed. While he worked primarily with the Meskawki, Dubuque also traded with the Sauk tribe and possibly others, and he sent lead and furs to trade at St. Louis; Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; Green Bay, Wisconsin; and Michilimackinac.

Mining would continue by the Meskwaki, then by European settlers until 1914. These activities left a complex of archaeological sites, including prehistoric native settlement sites, the mining village of the Meskwaki, Dubuque's trading post, the mining areas themselves, and later mining-related areas. They were listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on November 21, 1988, as four historic districts: Dubuque Trading Post-Village of Kettle Chief Archeological District, Mines of Spain Area Rural Community Archeological District, Mines of Spain Lead Mining Community Archeological District, and the Mines of Spain Prehistoric District.[6] The Julien Dubuque Monument, also located here, was individually listed on the NRHP on the same date. They were collectively named a National Historic Landmark District on November 4, 1993.[3]

Julien Dubuque Monument

When Dubuque died in 1810 he was buried according to the Meskawki burial customs. In 1897 a group of leaders from the City of Dubuque decided to build a monument to Julien Dubuque, who they considered their community's founder. It came at a time when the city's economy had declined and the decision to build the monument came from the local booster movement, which was common in many Midwestern cities at the time.[7] Human remains were discovered when footings were dug for the monument, but they were not identified and it could not be positively confirmed that this was actually the place Dubuque was buried. That is not as important as this was the place these people thought was the grave of Julien Dubuque, his wife Potosa, and her father Peosta, a Meskawki tribal chief.[7] The significance of the monument is less about who is supposedly buried here, and the historic events associated with them, as the historical trend (boosterism) that brought the monument about.[7]

The monument is a cylindrical tower that is 25 feet (7.6 m) high, 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, and walls that are 18 inches (46 cm) thick.[7] It is composed of locally quarried limestone and it has no roof. The monument features narrow windows, grillwork that covers its entrance, and a bronze plaque that reads "Julien Dubuque. Miner of the Mines of Spain. Founder of Our City. Died March 24, 1810". It was designed to have a "medieval design" and in that vein its ashlar block construction is capped with crenellations. It is located on the edge of a bluff above the mouth of Catfish Creek at the Mississippi River. The monument was originally designed to be situated in a rustic setting, but park features such as a roadway, footpaths, benches, and interpretive signs were added during the 20th century.

See also

References

- "Mines of Spain State Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. January 1, 2000. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Julien Dubuque's Mines". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- "Mines of Spain Archaeological Property Group". National Park Service. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- "Mines of Spain State Rec Area and E. B. Lyons". Iowa Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- "National Register of Historic Places Program: Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 1988. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- Joyce McKay. "Julien Dubuque Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved August 26, 2019. with photos

External links

- Mines of Spain State Recreation Area and E. B. Lyons Nature Center

- Friends of The Mines of Spain - Nature center information