Kanazawa

Kanazawa (金沢市, Kanazawa-shi) is the capital city of Japan's Ishikawa Prefecture. As of 1 January 2018, the city had an estimated population of 466,029 in 203,271 households, and a population density of 990 persons per km2.[1] The total area of the city was 468.64 square kilometres (180.94 sq mi).

Kanazawa

金沢市 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

Flag  Seal | |||||||||

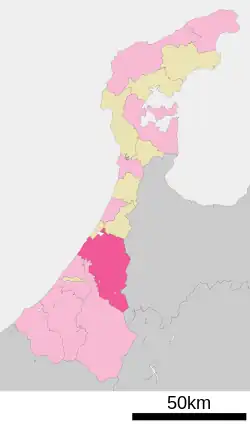

Location of Kanazawa in Ishikawa Prefecture | |||||||||

Kanazawa | |||||||||

| Coordinates: 36°33′39.8″N 136°39′23.1″E | |||||||||

| Country | Japan | ||||||||

| Region | Chūbu (Hokuriku) | ||||||||

| Prefecture | Ishikawa Prefecture | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Mayor | Takashi Murayama (from March 2022) | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| • Total | 468.64 km2 (180.94 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population (January 1, 2018) | |||||||||

| • Total | 466,029 | ||||||||

| • Density | 990/km2 (2,600/sq mi) | ||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (Japan Standard Time) | ||||||||

| City symbols | |||||||||

| Tree | Prunus mume | ||||||||

| Flower | Iris Salvia splendens Begonia Impatiens walleriana Pelargonium | ||||||||

| Phone number | 076-220-2111 | ||||||||

| Address | 1-1-1 Hirozaka, Kanazawa-shi, Ishikawa-ken 920-8577 | ||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||

Overview

Cityscape

Kanazawa Station (2013)

Kanazawa Station (2013)![Ōmichō Market [ja] (2013)](../I/Omichoichibakan004.jpg.webp) Ōmichō Market (2013)

Ōmichō Market (2013) Skyline of Kanazawa (2017)

Skyline of Kanazawa (2017) Central business district of Kanazawa (2020)

Central business district of Kanazawa (2020)![Center of Katamachi [ja] (2022)](../I/Katamachi_Crossing.jpg.webp) Center of Katamachi (2022)

Center of Katamachi (2022)

Geography

Kanazawa is located in north-western Ishikawa Prefecture in the Hokuriku region of Japan and is bordered by the Sea of Japan to the west and Toyama Prefecture to the east. The city sits between the Sai and Asano rivers. The eastern portion of the city is dominated by the Japanese Alps. Parts of the city are within the borders of the Hakusan National Park.

Climate

Kanazawa has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) characterized by hot, humid summers and cold winters with heavy snowfall.[2] Average temperatures are slightly cooler than those of Tokyo, with means approximately 4 °C (39 °F) in January, 12 °C (54 °F) in April, 27 °C (81 °F) in August, 17 °C (63 °F) in October, and 7 °C (45 °F) in December. The lowest temperature on record was −9.4 °C (15.1 °F) on January 27, 1904, with a maximum of 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) standing as a record since September 8, 1902.[3] The city is distinctly wet, with an average humidity of 73% and 193 rainy days in an average year. Precipitation is highest in the autumn and winter; it averages more than 250 millimetres (10 in)/ month November through January when the Aleutian Low is strongest, but it is above 125 millimetres (4.9 in) every month of the year.

| Climate data for Kanazawa (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1882−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.2 (70.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

33.7 (92.7) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

33.1 (91.6) |

28.4 (83.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.7 (14.5) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 256.0 (10.08) |

162.6 (6.40) |

157.2 (6.19) |

143.9 (5.67) |

138.0 (5.43) |

170.3 (6.70) |

233.4 (9.19) |

179.3 (7.06) |

231.9 (9.13) |

177.1 (6.97) |

250.8 (9.87) |

301.1 (11.85) |

2,401.5 (94.55) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 67 (26) |

53 (21) |

13 (5.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

24 (9.4) |

157 (62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 24.9 | 20.2 | 17.5 | 13.4 | 11.8 | 11.6 | 14.2 | 10.4 | 13.2 | 14.1 | 18.2 | 24.2 | 193.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 70 | 66 | 64 | 67 | 74 | 75 | 72 | 73 | 70 | 70 | 72 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.3 | 86.5 | 144.8 | 184.8 | 207.2 | 162.5 | 167.2 | 215.9 | 153.6 | 152.0 | 108.6 | 68.9 | 1,714.1 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[4] | |||||||||||||

Neighbouring municipalities

Demographics

Per Japanese census data,[5] the population of Kanazawa has recently plateaued after a long period of growth.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 361,379 | — |

| 1980 | 417,684 | +15.6% |

| 1990 | 442,868 | +6.0% |

| 2000 | 456,638 | +3.1% |

| 2010 | 462,361 | +1.3% |

| 2020 | 463,254 | +0.2% |

History

The name "Kanazawa" (金沢, 金澤), which literally means "marsh of gold", is said to derive from the legend of the peasant Imohori Togoro (literally "Togoro Potato-digger"), who was digging for potatoes when flakes of gold washed up. The well in the grounds of Kenroku-en is known as 'Kinjo Reitaku' (金城麗澤) to acknowledge these roots. The area where Kanazawa is was originally known as Ishiura, whose name is preserved at the Ishiura Shrine near Kenrokuen.

Muromachi period

During the Muromachi period (1336 to 1573), as the powers of the central shōguns in Kyoto was waning, Kaga Province came under the control of the Ikkō-ikki, followers of the teachings of priest Rennyo, of the Jōdo Shinshū sect, who displaced the official governors of the province, the Togashi clan, and established a kind of theocratic republic later known as "The Peasants' Kingdom". Their principal stronghold was the Kanazawa Gobo, on the tip of the Kodatsuno Ridge. Backed by high hills and flanked on two sides by rivers, it was a natural fortress, around which a castle town developed. This was the start of what would become the city of Kanazawa.

Sengoku period

In 1580, during the Sengoku period (1467 to 1615), Oda Nobunaga sent Shibata Katsuie, and his general Sakuma Morimasa, to conquer the Kaga Ikko-ikki.[6]

After overthrowing the "Peasant's Kingdom", Morimasa was awarded the province as his fief. However, after the assassination of Oda Nobunaga in 1582, he was displaced by Maeda Toshiie, who founded Kaga Domain. At the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Maeda sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu and thus was able to further enlarge his holdings to a massive 1.2 million koku — by far the largest feudal domain within the Tokugawa shogunate. The Maeda clan continued to rule Kaga Domain from Kanazawa Castle through the end of the Edo period.

Edo period

Maeda Toshiie and his successors greatly enlarged Kanazawa Castle and carefully planned the layout of the surrounding jōkamachi to meet strategic and defensive concerns. On April 14, 1631, a fire consumed much of the city, including the castle. In 1632 Maeda Toshitsune ordered the construction of a canal to bring water from the upper Sai River to the castle to alleviate a water shortage problem. Water was drawn from far upstream, and channeled through kilometres of canals and pipes carefully laid at a 750:1 slope for about 3.3 kilometres (2.1 miles) to the castle. The water was fed to the castle under the moat that lay between it and what is now Kenrokuen by an artesian well. The large lake in Kenrokuen, Kasumi-ga-Ike, acted as an emergency supply. Local legend has it that the lake has a plug, which could be pulled to increase the water in the moats. The series of moats were laid out in the early seventeenth century. Initially they were dry, but later connected to the rivers. The Inner Moat was dug in only 27 days, and averaged about four to five feet wide. The Outer Moat took a bit longer, and averages some six to nine feet in width. Though much of the Inner Moat has been filled in, large sections of the Outer Moat remain. The earth removed from the moat was piled into ridges along the inner side, as an added defence measure.

.jpeg.webp)

Before the Maeda clan arrived in Kanazawa, the town had a population of only 5,000.[7] However, thanks to Maeda efforts, that number rose quickly. By 1700, Kanazawa rivaled Rome, Amsterdam, and Madrid in size with its population of over 100,000.[8] The Maeda summoned samurai retainers to live in Kanazawa and offered a set of incentives to attract the artisans and merchants needed to support the samurai population.[9] Chartered merchants and artisans received economic, social, and political privileges in exchange for moving to the city: they were guaranteed business, exempt from certain taxes, and given pieces of land for shops and residences.[10] These merchants and artisans were at the top of the chōnin, or townsman, social class.

Other merchants and artisans, who made up the rest of the chōnin, came without such promises. Some were first hired as servants for samurai or wealthy merchant families and decided to stay in the city even after their contracts expired, though most moved to Kanazawa for no reason other than the commercial opportunities the city presented. The government further facilitated growth by responding to the needs of these newcomers with projects like the Sai River Project. Because the Sai River split in two and the castle was located in the center, a part of the riverbed was unusable. In the 1610s, the construction project diverted the secondary stream into the main river, thus creating usable land, where four new wards opened for chōnin settlement.[11] Some of these poorer merchants became successful enough to compete with chartered merchants for city administration positions, but many supported themselves by making and selling low cost goods, such as umbrellas and straw sandals, for mass consumption. This signifies that the commoner population of Kanazawa began to generate its own consumption demands, thus stimulating even more growth.[12]

Kanazawa flourished largely because of a mutually beneficial relationship between the daimyō and the chōnin. The samurai relied on merchants and artisans for goods and services, while the chōnin were able to thrive because of the protection that the daimyō provided. Coming out of the Sengoku Period, castle towns were particularly appealing because of their security and defenses.[13] Kanazawa's growth was indicative of a larger trend in Japan from 1580 to 1700: urbanization. In those 120 years, the population of the country nearly doubled, reaching approximately 30,000,000, and the percentage of people living in urban towns of more than 10,000 residents grew more than tenfold.[14] Kanazawa continued to grow until 1710, when the chōnin population reached 64,987, and the city's total reached approximately 120,000. The population then stabilized.[15] Much of the economic and population growth in Kanazawa, as well as in other Japanese castle towns, occurred during Japan's closed country policy (sakoku). Beginning in the 1630s, Japan had little or no influence from other countries. However, this phase was clearly not a sign of backwardness or decline. The growth that Japan experienced while operating under sakoku policy was largely possible because of castle towns such as Kanazawa. They facilitated growth in a way that did not require foreign influence, thus contributing to the success and stability of Japan at the time.

The vast wealth of the Maeda was channeled into arts and crafts, rather than military pursuits, and Kanazawa became the centre of the "Million-koku Culture", which helped ease suspicions held by the shogunate over the domain's wealth and the status of its daimyō as an "Outer Lord" or Tozama daimyō. The third daimyō Maeda Toshitsune, formed the "Kaga Workmanship Office" and promoted lacquer and gold-and-lacquer-work; and the fifth daimyō, Maeda Tsunanori, collected works of art and artisans from all over the country. Kanazawa was one of the largest cities in Japan throughout the Edo period.

Nagamachi Buke Yashiki District

Nagamachi Buke Yashiki District.jpeg.webp) Kazue Machi

Kazue Machi.jpg.webp) Higashiyamahigashi (Higashi-Chaya)

Higashiyamahigashi (Higashi-Chaya) Nishi Chaya-gai (Nishi-Chaya)

Nishi Chaya-gai (Nishi-Chaya)

Meiji period

Following the Meiji restoration, the modern city of Kanazawa was created on April 1, 1889, with the establishment of the modern municipalities system. The borders of the city gradually expanded by annexing neighbouring towns and villages bringing the area of the city from its initial 10.40 square kilometers to its present 468.64 square kilometers.

The Fourth High School Memorial Museum of Cultural Exchange, Ishikawa

The Fourth High School Memorial Museum of Cultural Exchange, Ishikawa

Kanazawa Literary Hall

Kanazawa Literary Hall

Heisei period

On April 1, 1996, Kanazawa was proclaimed a Core city with increased local autonomy.

Government

Kanazawa has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city legislature of 38 members. Since March 2022 the mayor is Takahasi Murayama. His predecessor was Yukiyoshi Yamano who had been mayor since December 2010.[16] Yamano resigned to run for the seat of governor of Ishikawa prefecture.

The city is the seat of the Ishikawa Prefectural Assembly, and contributes 16 of the 43 members of that body.

In terms of national politics, the city forms the Ishikawa 1st District with one seat in the lower house of the Diet of Japan.

External relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Kanazawa is twinned with the following cities:[17]

| City | Country | State | since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffalo | New York | December 18, 1962 | |

| Porto Alegre | Rio Grande do Sul | March 20, 1967 | |

| Irkutsk | Irkutsk Oblast | March 20, 1967 | |

| Ghent | Flemish Region | October 4, 1971[18] | |

| Nancy | Grand Est | October 12, 1973 | |

| Suzhou | Jiangsu | June 13, 1981 | |

| Jeonju | Jeollabuk-do | April 30, 2002 |

Economy

Kanazawa is a regional commercial centre and transportation hub for Ishikawa Prefecture. It remains noted for its traditional handicrafts industry, including the production of Kutani ware ceramics, and is a major tourist destination.[19]

Education

Universities and colleges

- Kanazawa University – is a large national university that traces its history back to the founding of a small medical school in 1862. Its immediate predecessor was the Fourth Upper High School, one of the elite preparatory schools for the Imperial Universities before the war. Many prominent politicians and other notables were graduates of 'Shiko', as it was known.

- Kanazawa College of Art, a public university operated by the city government

- Hokuriku University – a private liberal arts college with a business management department specializing in foreign languages and a School of Pharmacy

- Kanazawa Seiryo University, a private business and education university

- Kanazawa Gakuin University, private liberal arts college

- Hokuriku Gakuin University, a private Christian university which celebrated the 125th anniversary of its founding in 2010, with associated junior college

- Kanazawa Gakuin College, a private junior college

- Seiryo Women's Junior College, a private women's junior college

Primary and secondary education

Kanazawa has 58 public elementary schools operated by the city government and one public elementary school operated by the national government (associated with Kanazawa University) and one private elementary school.

The city has 25 public middle schools operated by the city government, one public combined middle/high school operated by the Ishikawa Prefectural Board of Education, one public combined middle/high school operated by the national government (associated with Kanazawa University) and two private combined middle/high schools.

Aside from the above combined middle/high schools, Kanazawa has 11 public high schools operated by the Ishikawa Prefectural Board of Education, one public industrial high school operated by the city government and four private high schools.

Ishikawa Prefecture also operates five special education schools in Kanazawa.

Transport

Airways

The nearest airport is Komatsu Airport in the city of Komatsu.

Railways

Kanazawa is served by the JR West Hokuriku Main Line and the Hokuriku Railroad. Since 14 March 2015, the city is also served by the Hokuriku Shinkansen, shortening the trip from Tokyo to Kanazawa to around 2 and a half hours. With the opening of the Shinkansen line in March 2015, part of the Hokuriku Main Line which was formerly operated by JR West was separated and operated by the third-sector company IR Ishikawa Railway.

Conventional lines

.svg.png.webp) West Japan Railway Company (JR West)

West Japan Railway Company (JR West)

IR Ishikawa Railway (IR)

IR Ishikawa Railway (IR)

Hokuriku Railroad (Hokutetsu)

Hokuriku Railroad (Hokutetsu)

- Asanogawa Line: Hokutetsu-Kanazawa - Nanatsuya -Kamimoroe - Isobe - Waridashi -Mitsukuchi - Mitsuya - Okobata - Kitama - Kagatsume

- Ishikawa Line: Magae - Nuka-Jūtakumae - Otomaru -Shijima

Expressway

- Hokuriku Expressway

- Noto Satoyama Expressway

Japan National Route

Seaport

- Port of Kanazawa

Local attractions

Kanazawa was one of the few major Japanese cities to be spared destruction by air raids during World War II, and as a result, much of Kanazawa's considerable architectural heritage has been preserved.

Kenrokuen Garden is by far the most famous part of Kanazawa. Originally built as the outer garden of Kanazawa Castle, it was opened to the public in 1875. It is considered one of the "three great gardens of Japan" and is filled with a variety of trees, ponds, waterfalls and flowers stretching over 25 acres (10 ha). In winter, the park is notable for its yukitsuri – ropes attached in a conical array to trees to support the branches under the weight of the heavy wet snow, thereby protecting the trees from damage.

Outside Kenrokuen is the Ishikawa-mon, the back gate to Kanazawa Castle. The original castle was largely destroyed by fire in 1888 but has been partially restored. The Seisonkaku Villa was built in 1863 by Maeda Nariyasu (13th daimyō of Kaga Domin) for his mother, Takako. It was originally called Tatsumi Goten (Tatsumi Palace). Much of it has been dismantled, but what remains is one of the most elegant remaining feudal lord villas in Japan. The villa stands in a corner of Kenrokuen; separate admission fees apply. Notable features are the vividly coloured walls of the upper floor, with purple or red walls and dark-blue ceilings (red walls—benigara—are a Kanazawa tradition), and the custom-made English carpet in the audience chamber.

The Oyama-jinja shrine, which is considered an Important Cultural Property, is also in Kanazawa. It is noted for its imposing three-story Shinmon gate influenced by Dutch design, built in 1875, with its brightly coloured stained-glass windows.

Kanazawa's Myōryūji Temple also known as the Ninja-dera (Ninja Temple) is an amalgamation of traditional temple architecture, hidden doors, passageways, and hidden escape routes. Local legend has it that the temple, with its hidden doors and passageways, was intended as a secret refuge for the local rulers in the case of an external threat.

Mount Utatsu gives a commanding view of the city of Kanazawa. Toyokuni Shrine, Utatsu Shrine (a Tenman-gū), and Atago Shrine, known together as the Mount Utatsu Three Shrines, are found on the mountain. A monument to author Shūsei Tokuda is located near the summit.

Traditional architecture

Kanazawa boasts numerous Edo period (1603–1867) former geisha houses in the Higashi Geisha District, across the Asano river (with its old stone bridge) out from central Kanazawa. Nearby is the Yougetsu Minshuku which sits at one end of one of the most photographed streets in Japan. This area retains the look and feel of pre-modern Japan, its two-story wooden façades plain and austere. The effect is accentuated by the early morning mist. At night, the street is lit by recreated Taishō-period streetlamp.

Houses were taxed on the width of the frontage, leading to the development of many long, thin houses. Unlike samurai houses, they were built right up to the road and directly abutted their neighbours. They were two-storied, though the upper floor was used mainly for storage, particularly at the front of the house, above the shop area. One feature of Kanazawa merchant houses is the long earth corridor that runs from the front door to the rear of the house. This was usually on one side, and the rooms opened off it. The typical merchant's house, would have the shop area, then a couple of inner rooms, with the most important room at the back, facing the inner garden. Beyond that was the kitchen area, and at the rear of the house would be a thick-walled fireproof storehouse.

Though very few from the Edo period remain, the basic style remained unchanged until the World War II. One notable feature of the design is the 'sode-utatsu' wings extending forward on the sides of the upper floor. Their exact purpose is not certain, but one theory is that they were wind blockers, which is logical given Kanazawa's weather. Snow was also a significant factor in house design. The roofs sloped into a central garden that was designed to allow snow to collect as much as to provide light to the rear. While the sea of black-glazed tiles sparkling in the sun is a common tourist image of Kanazawa today, the traditional architectural style used wooden boards held down by stones. Due to the heavy snowfalls of the Japan Sea coast, traditional tiles were considered to be too heavy. The use of tiles on the frontage and boards under the eaves is to prevent snow damage.

Samurai areas

Large-scale reorganization of the samurai areas took place in 1611. Areas had been ordained by income. As the total income of the domain had increased fourfold in the past couple of decades, there was some reorganization to be done. And room had to be found for the 14 families with incomes over 3,000 koku and their retainers, not to mention the large number of samurai who arrived from Takaoka (in Toyama Prefecture) with Maeda Toshitsune, the third lord, when he took up his position. The richest families were moved out of the castle and given massive estates throughout the city. Their own retainers were housed in huge complexes nearby. The most notable example in Kanazawa is Honda-machi, where the retainers of the rich and powerful Honda family lived, in what was almost a town within a town.

In most cases, even with large fiefs like Sendai and Satsuma, samurai tended to live on their own land. But in Kaga all samurai, regardless of income, lived in Kanazawa. When Kanazawa was finished in more or less its final form in the late 17th century, over three-quarters of it was samurai housing. Nearest the castle were the huge estates of the Eight Houses (chief vassals) and their own retainers. For every 100 koku of income, a samurai was given about 550 square metres of land, and average of the "middle-class" samurai was 800, which is huge compared to modern Japanese housing. The richest vassal family, the Hondas, had a 50,000 koku income. The minimum for daimyo level was 10,000 koku, and apart from the Eight Houses, some twelve families had incomes in excess of this. Kanazawa was filled with huge mansions.

Size and location of samurai housing was determined by income and standing. The richest and most powerful samurai in Kanazawa had their own men, often hundreds of them, who were housed in large areas that usually adjoined the main house. Samurai houses shared a similar basic pattern: a single-floored residence, usually fairly square or rectangular in plan, surrounded by a garden – both the vegetable and the decorative kinds. The roof was gabled and faced the road. The boundary wall was usually made of beaten earth, topped with tiles. There are a number of them around in the city, most notably in the Nagamachi area. The size and height of the wall and the entry gate were also dictated by rank. Samurai over 400 koku in income had a stable gate, used to house guards and horses.

Though the Nagamachi area is promoted in the tourist brochures as the 'samurai area', the overwhelming majority of the houses are not samurai houses, but modern post-war housing. There are very few genuine samurai houses in Kanazawa. (This is because after the Meiji Restoration the samurai found themselves bereft of their traditional income, and many of them ended up selling off their estates, which were turned into fields before being redeveloped as modern housing before World War II.)

Temple areas

One distinctive aspect of Kanazawa, and other castle towns, is the clustering of temples near the entrances. When Kanazawa was ruled by the Ikkō, the temples were all Jōdo Shinshū, the Ikkō sect. After the Ikkō were defeated, other sects moved in: Sōtō, Shingon, Hokke, Ji, etc. They were placed in their present locations by around 1616. In the Teramachi ("temple town" area), they were lined up side by side along a long straight road leading to the foot of Nodayama. Defensive purposes have often been argued for this type of planning, and it is true that the wide spaces, thick walls, and large halls of temples were able to be used as emergency fortifications. However, to what extent this influenced the layout is not certain. It was, in Kanazawa's case at least, never put to the test.

On the other side of town, the Utatsuyama temple district, at the foot of the hill of the same name, has smaller temples and twisty roads.

Geisha areas

Kanazawa had a further expansion in 1661, when many samurai who had followed their retired Lord Toshitsune to his villa at Komatsu returned after his death. They built houses on the fringes of the city, with street layouts almost totally unplanned. These areas are some of the most labyrinthine parts of the city, but this was not done for defensive purposes. By this time, peace was quite firmly secured. To alleviate crowding from the continual (illegal) inflow of peasants and other migrants, residents were permitted to rent land from neighbouring farmers. These areas are some of the most convoluted, as the roads were laid out on the old winding paths through the fields.

Thus Kanazawa attained the form that it kept for the rest of the Edo period — even now the majority of roads in the old city are little changed in form from two centuries ago. The only major change was the creation of geisha districts (hanamachi) at the foot of Utatsuyama and over the Sai River in 1820, to control and regulate pleasure houses and prostitutes (bath girls; 湯女). However, conservative factions regained control of the Kaga government, and the geisha districts were abolished a decade later. The districts were made legal again just before the Meiji Restoration, and stayed that way until prostitution was officially outlawed in 1954. The geisha areas were out of bounds to samurai; they were patronised by rich merchants and artisans, who would compete with each other to spend the most money on parties.

The geisha house, or "tea house" (ochaya) as it is commonly called, is superficially similar to the merchant houses (in the same way the samurai houses are superficially similar to farmhouses). However, unlike the merchant houses, where the second floor at the front was for storage, and thus very low, the second story of tea houses are much higher, because the upper floor was used as the main entertaining area.

The upper floors are faced with sliding wooden shutters which would be open in the day or when there was a party going on. The bottom floor is faced with the unique, extremely fine latticework that is known as Kaga lattice. The standard of décor was far higher than most merchant houses, at least to the extent allowed by the Sumptuary Laws that the Shogunate passed. Due in part to the long gloomy winters, Kaga décor is far brighter than the drab earth browns and greens and ochres of Kyoto style: bold bright scarlets (benigara; 紅柄) and ultramarines were popular. The upper floor of the Seisonkaku Villa in Kenrokuen is particularly boldly decorated, with purple and black walls as well.

Culture

Hyakumangoku Matsuri and Asano-gawa Enyukai are the major festivals held in Kanazawa.

Kanazawa-haku is gold that is beaten into a paper-like sheet. Gold leaf plays a prominent part in the city's cultural crafts, to the extent that there is the Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum. It is found throughout Kanazawa and Ishikawa; Kanazawa produces 99% of Japan's high-quality gold leaf. The gold leaf that covers the famous Golden Pavilion in Kyoto was produced in Kanazawa. Gold leaf is even put into food. The city is famous for tea with gold flakes, which is considered by the Japanese people to be good for health and vitality. Kanazawa lacquerware (Kanazawa shikki), a high-quality lacquerware traditionally decorated with gold dust, is also well known.

'Cultural landscape in Kanazawa. Tradition and culture in the castle town' has been designated an Important Cultural Landscape.[20]

Local cuisine

Kanazawa is known for its traditional Kaga Cuisine, with seafood a specialty. The sake produced in this region, derived from the rice grown in Ishikawa Prefecture with the considerable precipitation of the Hokuriku region, allowing for an ample supply of clean, fresh water is considered to be of high quality. Omicho market is a market in the middle of the city, originally open-air, and now covered, which dates back to the Edo period. Most of the shops there sell seafood.

Popular Food and Drink in Kanazawa include:[21]

- Wagashi (Japanese confections) of Kanazawa - Admired for its ability to be sampled by the 5 senses of taste, smell, touch, sight and hearing.

- Jibuni - a soup dish consisting of duck, vegetables, and wheat flour. It is said to symbolize Kanazawa.

- Kanazawa Sake - refined sake from the region.

- Kaga Vegetables - premium vegetables supporting the traditional cuisine of old Kanazawa.

- Kaburazushi - a traditional fermented dish that has existed since the Edo Era.

Notable people

Politicians and public servants

- Nobuyuki Abe (1875 ~ 1953; 36th Prime Minister of Japan)

- Takuo Godō (Vice admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy)

- Yoichi Hatta (Engineer of Governor-General of Taiwan)

- Hayakawa Senkichirō (Politician, President of South Manchuria Railway)

- Senjūrō Hayashi (33rd Prime Minister of Japan)

- Tetsuo Kutsukake (Cabinet minister)

- Ryūtarō Nagai (Cabinet minister)

- Nakahashi Tokugorō (Cabinet minister)

- Naoki Okada (Politician)

Business people

- Inokuchi Ariya (1856 - 1923; Founder of Ebara Corporation)

- Takaaki Kidani (Founder and President of Bushiroad)

- Shitagau Noguchi (Founder of Nichitsu zaibatsu)

- Masatsune Ogura (President of Sumitomo Group)

Academics

- Hisashi Kimura (1870 – 1943; Astronomer)

- Yoshio Koide (Physicist)

- Miyake Setsurei (Philosopher)

- D. T. Suzuki (Zen Buddhism scholar)

- Gaisi Takeuti (Mathematician)

- Yoshirō Taniguchi (Architect)

Art and culture

- Kyōka Izumi (1987 ~ 1939; Novelist)

- Clifton Karhu (American artist specializing in woodblock prints)

- Yasushi Kataoka (Architect)

- Natsuo Kirino (Novelist)

- Murō Saisei (Novelist, Poet)

- Shōgyo Ōba (Maki-e lacquer artist, Living National Treasure of Japan)

- Takumi Shibano (Science-fiction translator and author)

- Yoshirō Taniguchi (Architect)

- Shūsei Tokuda (Novelist)

Media and artists

- Azumi Inoue (Singer)

- Tatsuya Isaka (Actor)

- Takeshi Kaga (Actor)

- Toshiko Koshijima (b. 1980; Singer of the band Capsule)

- Ryutaro Morimoto (Singer)

- Yasutaka Nakata (b. 1980; Producer of Capsule)

- Mamiko Noto (Voice actress)

- Shun Shioya (Actor)

- Ryōko Shintani (Voice actress)

- Aya Suzaki (Voice actress)

- Miki Takakura (Actress)

- Misato Tanaka (Actress)

- Mayuko Watanabe (Journalist)

- Kazuki Yao (Voice actor)

Athletics

- Kenkichi Oshima (1908 ~ 1985; Triple jump bronze medalist at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles)

- Takanori Sugibayashi (b. 1976; Triple jumper in the 2000 and 2004 Olympics)

Others

- Igor Fraga (Motorsports)

- Keiji Kojima (Keirin)

- Yu Koshikawa (Volleyball)

- Akira Masuda (Karate)

- Keita Masuda (Badminton)

- Kaori Matsumoto (Judo)

- Hiroshi Nakano (Rower)

- Rana Nakano (Trampolining)

- Yuichi Nakayama (Motorsports)

- Naoya Nomura (Professional wrestling [puroresu])

- Hisakatsu Oya (Professional wrestling [puroresu])

- Katsuhiko Sumii (Horse trainer)

References

- Official statistics page

- Kanazawa climate data

- 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値). Japan Meteorological Agency.

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- Kanazawa population statistics

- Turnbull, Stephen (2000). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & C0. p. 230. ISBN 1854095234.

- Totman, Conrad (1993). Early Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 152.

- McClain, James (1982). Kanazawa: A Seventeenth-Century Japanese Castle Town. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 2.

- McClain, James (Summer 1980). "Castle Towns and Daimyo Authority: Kanazawa in the Years 1583-1630". Journal of Japanese Studies. 6 (2): 274. doi:10.2307/132323. JSTOR 132323.

- McClain, James (Summer 1980). "Castle Towns and Daimyo Authority: Kanazawa in the Years 1583-1630". Journal of Japanese Studies. 6 (2): 279–85. doi:10.2307/132323. JSTOR 132323.

- McClain, James (Summer 1980). "Castle Towns and Daimyo Authority: Kanazawa in the Years 1583–1630". Journal of Japanese Studies. 6 (2): 284–88. doi:10.2307/132323. JSTOR 132323.

- McClain, James (Summer 1980). "Castle Towns and Daimyo Authority: Kanazawa in the Years 1583-1630". Journal of Japanese Studies. 6 (2): 284–288. doi:10.2307/132323. JSTOR 132323.

- McClain, James (Summer 1980). "Castle Towns and Daimyo Authority: Kanazawa in the Years 1583–1630". Journal of Japanese Studies. 6 (2): 297. doi:10.2307/132323. JSTOR 132323.

- McClain, James (1982). Kanazawa: A Seventeenth-Century Japanese Castle Town. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 1.

- McClain, James (Summer 1980). "Castle Towns and Daimyo Authority: Kanazawa in the Years 1583–1630". Journal of Japanese Studies. 6 (2): 274. doi:10.2307/132323. JSTOR 132323.

- Profile of Mayor, Kanazawa City (in Japanese) on 2018-02-22

- かなざわの姉妹都市 [Sister cities of Kanazawa] (in Japanese). Kanazawa City. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- "Ghent Zustersteden". Stad Gent (in Dutch). City of Ghent. Retrieved 2013-07-20.

- Campbell, Allen; Nobel, David S (1993). Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha. p. 732. ISBN 406205938X.

- "Database of Registered National Cultural Properties". Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- "Kanazawa City Travel Guide | Planetyze". Planetyze. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

External links

Kanazawa travel guide from Wikivoyage

Kanazawa travel guide from Wikivoyage- Kanazawa City official website (in Japanese)

- Kanazawa City official website (in English)

- Kanazawa Tourist Information Guide

- Kanazawa attractions (in English)

- Kanazawa Tourist Information Guide from 2008 (in English)

.jpg.webp)