Atlas (mythology)

In Greek mythology, Atlas (/ˈætləs/; Greek: Ἄτλας, Átlas) is a Titan condemned to hold up the heavens or sky for eternity after the Titanomachy. Atlas also plays a role in the myths of two of the greatest Greek heroes: Heracles (Hercules in Roman mythology) and Perseus. According to the ancient Greek poet Hesiod, Atlas stood at the ends of the earth in extreme west.[1] Later, he became commonly identified with the Atlas Mountains in northwest Africa and was said to be the first King of Mauretania (modern-day Morocco and west Algeria, not to be confused with the modern-day country of Mauritania).[2] Atlas was said to have been skilled in philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy. In antiquity, he was credited with inventing the first celestial sphere. In some texts, he is even credited with the invention of astronomy itself.[3]

| Atlas | |

|---|---|

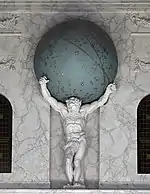

The Farnese Atlas, the oldest surviving representation of the celestial spheres. | |

| Abode | Western edge of Gaia (the Earth) |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | |

| Consort | |

| Children | |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Atlas |

Atlas was the son of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Asia[4] or Clymene.[5] He was a brother of Epimetheus and Prometheus.[6] He had many children, mostly daughters, the Hesperides, the Hyades, the Pleiades, and the nymph Calypso who lived on the island Ogygia.[7]

The term Atlas has been used to describe a collection of maps since the 16th century when Flemish geographer Gerardus Mercator published his work in honour of the mythological Titan.

The "Atlantic Ocean" is derived from "Sea of Atlas". The name of Atlantis mentioned in Plato's Timaeus' dialogue derives from "Atlantis nesos" (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος), literally meaning "Atlas's Island".[8]

Etymology

The etymology of the name Atlas is uncertain. Virgil took pleasure in translating etymologies of Greek names by combining them with adjectives that explained them: for Atlas his adjective is durus, "hard, enduring",[9] which suggested to George Doig[10] that Virgil was aware of the Greek τλῆναι "to endure"; Doig offers the further possibility that Virgil was aware of Strabo's remark that the native North African name for this mountain was Douris. Since the Atlas mountains rise in the region inhabited by Berbers, it has been suggested that the name might be taken from one of the Berber languages, specifically from the word ádrār "mountain".[11]

Traditionally historical linguists etymologize the Ancient Greek word Ἄτλας (genitive: Ἄτλαντος) as comprised from copulative α- and the Proto-Indo-European root *telh₂- 'to uphold, support' (whence also τλῆναι), and which was later reshaped to an nt-stem.[12] However, Robert S. P. Beekes argues that it cannot be expected that this ancient Titan carries an Indo-European name, and he suggests instead that the word is of Pre-Greek origin, as such words often end in -ant.[12]

Mythology

War and punishment

Atlas and his brother Menoetius sided with the Titans in their war against the Olympians, the Titanomachy. When the Titans were defeated, many of them (including Menoetius) were confined to Tartarus, but Zeus condemned Atlas to stand at the western edge of the earth and hold up the sky on his shoulders. Atlas did not want to do this resulting in him being sent to hell.[13] Thus, he was Atlas Telamon, "enduring Atlas," and became a doublet of Coeus, the embodiment of the celestial axis around which the heavens revolve.[14]

A common misconception today is that Atlas was forced to hold the Earth on his shoulders, but Classical art shows Atlas holding the celestial spheres, not the terrestrial globe; the solidity of the marble globe borne by the renowned Farnese Atlas may have aided the conflation, reinforced in the 16th century by the developing usage of atlas to describe a corpus of terrestrial maps.

Encounter with Perseus

The Greek poet Polyidus c. 398 BC[15] tells a tale of Atlas, then a shepherd, encountering Perseus who turned him to stone. Ovid later gives a more detailed account of the incident, combining it with the myth of Heracles. In this account Atlas is not a shepherd, but a king.[16] According to Ovid, Perseus arrives in Atlas's Kingdom and asks for shelter, declaring he is a son of Zeus. Atlas, fearful of a prophecy that warned of a son of Zeus stealing his golden apples from his orchard, refuses Perseus hospitality.[17] In this account, Atlas is turned not just into stone by Perseus, but an entire mountain range: Atlas's head the peak, his shoulders ridges and his hair woods. The prophecy did not relate to Perseus stealing the golden apples but to Heracles, another son of Zeus, and Perseus's great-grandson.[18]

Encounter with Heracles

.jpg.webp)

One of the Twelve Labours of the hero Heracles was to fetch some of the golden apples that grow in Hera's garden, tended by Atlas's reputed daughters, the Hesperides (which were also called the Atlantides), and guarded by the dragon Ladon. Heracles went to Atlas and offered to hold up the heavens while Atlas got the apples from his daughters.[19]

Upon his return with the apples, however, Atlas attempted to trick Heracles into carrying the sky permanently by offering to deliver the apples himself, as anyone who purposely took the burden must carry it forever, or until someone else took it away. Heracles, suspecting Atlas did not intend to return, pretended to agree to Atlas's offer, asking only that Atlas take the sky again for a few minutes so Heracles could rearrange his cloak as padding on his shoulders. When Atlas set down the apples and took the heavens upon his shoulders again, Heracles took the apples and ran away.

In some versions,[20] Heracles instead built the two great Pillars of Hercules to hold the sky away from the earth, liberating Atlas much as he liberated Prometheus.

Other mythological characters

King of Atlantis

According to Plato, the first king of Atlantis was also named Atlas, but that Atlas was a son of Poseidon and the mortal woman Cleito.[21] The works of Eusebius[22] and Diodorus[3] also give an Atlantean account of Atlas. In these accounts, Atlas' father was Uranus and his mother was Gaia. His grandfather was Elium "King of Phoenicia" who lived in Byblos with his wife Beruth. Atlas was raised by his sister, Basilia.[23][24][25]

King of Mauretania

Atlas was also a legendary king of Mauretania, the land of the Mauri in antiquity roughly corresponding with modern Morocco and Algeria . In the 16th century, Gerardus Mercator put together the first collection of maps to be called an "Atlas" and devoted his book to the "King of Mauretania".[24][26]

Atlas became associated with Northwest Africa over time. He had been connected with the Hesperides, or "Nymphs", which guarded the golden apples, and Gorgons both of which were said to live beyond Ocean in the extreme west of the world since Hesiod's Theogony.[27] Diodorus and Palaephatus mention that the Gorgons lived in the Gorgades, islands in the Aethiopian Sea. The main island was called Cerna, and modern-day arguments have been advanced that these islands may correspond to Cape Verde due to Phoenician exploration.[28] The Northwest Africa region emerged as the canonical home of the King via separate sources. In particular, according to Ovid, after Perseus turns Atlas into a mountain range, he flies over Aethiopia, the blood of Medusa's head giving rise to Libyan snakes. By the time of the Roman Empire, the habit of associating Atlas's home to a chain of mountains, the Atlas Mountains, which were near Mauretania and Numidia, was firmly entrenched.[29]

Other

The identifying name Aril is inscribed on two 5th-century BC Etruscan bronze items: a mirror from Vulci and a ring from an unknown site.[30] Both objects depict the encounter with Atlas of Hercle—the Etruscan Heracles—identified by the inscription; they represent rare instances where a figure from Greek mythology was imported into Etruscan mythology, but the name was not. The Etruscan name Aril is etymologically independent.

Genealogy

Sources describe Atlas as the father, by different goddesses, of numerous children, mostly daughters. Some of these are assigned conflicting or overlapping identities or parentage in different sources.

Hyginus, in his Fabulae, adds an older Atlas who is the son of Aether and Gaia.[38]

Cultural influence

Atlas' best-known cultural association is in cartography. The first publisher to associate the Titan Atlas with a group of maps was the print-seller Antonio Lafreri, who included a depiction of the Titan on the engraved title-page he applied to his ad hoc assemblages of maps, Tavole Moderne Di Geografia De La Maggior Parte Del Mondo Di Diversi Autori (1572).[39] However, Lafreri did not use the word "Atlas" in the title of his work; this was an innovation of Gerardus Mercator, who named his work Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati (1585-1595),[40] using the word Atlas as a dedication specifically to honour the Titan Atlas, in his capacity as King of Mauretania, a learned philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer. In psychology, Atlas is used metaphorically to describe the personality of someone whose childhood was characterized by excessive responsibilities.[41] Ayn Rand's political dystopian novel Atlas Shrugged (1957) references the popular misconception of Atlas holding up the entire world on his back by comparing the capitalist and intellectual class as being "modern Atlases" which hold the modern world up at great expense to themselves.

Gallery

Atlas supports the terrestrial globe on a building in Collins Street, Melbourne, Australia.

Atlas supports the terrestrial globe on a building in Collins Street, Melbourne, Australia. Nautilus Cup. This drinking vessel, for court feasts, depicts Atlas holding the shell on his back.[42] The Walters Art Museum

Nautilus Cup. This drinking vessel, for court feasts, depicts Atlas holding the shell on his back.[42] The Walters Art Museum Sculpture of Atlas, Praza do Toural, Santiago de Compostela

Sculpture of Atlas, Praza do Toural, Santiago de Compostela

Greco-Buddhist (c. AD 100) Atlas, supporting a Buddhist monument, Hadda, Afghanistan

Greco-Buddhist (c. AD 100) Atlas, supporting a Buddhist monument, Hadda, Afghanistan Atlas inside the Royal Palace, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Atlas inside the Royal Palace, Amsterdam, Netherlands_corr.jpg.webp) Statues of Atlas on the exterior of Catherine Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, Pushkin, Saint Petersburg

Statues of Atlas on the exterior of Catherine Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, Pushkin, Saint Petersburg

Genealogy

See also

- Atlas (architecture)

- Bahamut, a rough analogue from Arabian mythology, and other members of Category:World-bearing animals

- Farnese Atlas

- Upelluri

Notes

- Hesiod, Theogony 517–520.

- Smith, s.v. Atlas

- Referencing Diodorus:

- "[Atlas] perfected the science of astrology and was the first to publish to mankind the doctrine of the sphere. and it was for this reason that the idea was held that the entire heavens were supported upon the shoulders of Atlas, the myth darkly hinting in this way at his discovery and description of the sphere." Bibliotheca historica, Book III 60.2

- "Atlas was so grateful to Heracles for his kindly deed that he not only gladly gave him such assistance as his Labour called for, but he also instructed him quite freely in the knowledge of astrology. For Atlas had worked out the science of astrology to a degree surpassing others and had ingeniously discovered the spherical nature of the stars, and for that reason was generally believed to be bearing the entire firmament upon his shoulders. Similarly in the case of Heracles, when he had brought to the Greeks the doctrine of the sphere, he gained great fame, as if he had taken over the burden of the firmament which Atlas had borne, since men intimated in this enigmatic way what had actually taken place." Bibliotheca historica, Book IV 27.4-5

- Apollodorus, 1.2.3.

- Hesiod,Theogony 507. It is possible that the name Asia became preferred over Hesiod's Clymene to avoid confusion with what must be a different Oceanid named Clymene, who was mother of Phaethon by Helios in some accounts.

- Roman, Luke; Roman, Monica (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology. Infobase Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4381-2639-5.

- Homer, Odyssey, 1.14, 1.50. Calypso is sometimes referred to as Atlantis (Ατλαντίς), which means the daughter of Atlas, see the entry Ατλαντίς in Liddell & Scott, and also Hesiod, Theogony, 938.

- "What does "Atlantis" mean? And why is the Space Shuttle Atlantis named after something underwater?". 8 July 2011.

- Aeneid iv.247: "Atlantis duri" and other instances; see Robert W. Cruttwell, "Virgil, Aeneid, iv. 247: 'Atlantis Duri'" The Classical Review 59.1 (May 1945), p. 11.

- George Doig, "Vergil's Art and the Greek Language" The Classical Journal 64.1 (October 1968, pp. 1-6) p. 2.

- Strabo, 17.3;

- Beekes, Robert; van Beek, Lucien (2010). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Vol. 1. Brill. p. 163.

- Hesiod, Theogony 517–520; Gantz (1993), p. 46

- The usage in Virgil's maximum Atlas axem umero torquet stellis ardentibus aptum (Aeneid, iv.481f, cf vi.796f), combining poetic and parascientific images, is discussed in P. R. Hardie, "Atlas and Axis" The Classical Quarterly N.S. 33.1 (1983:220-228).

- Polyeidos, fr. 837 Campbell; Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.627.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.617 ff. (on-line English translation at Theoi Project).

- William Godwin (1876). Lives of the Necromancers. London, F. J. Mason. p. 39.

- Ogden (2008), pp. 49, 108, 114

- Diodorus Siculus, 4.27.2; Gantz (1993), pp. 410–413.

- a lost passage of Pindar quoted by Strabo (3.5.5) was the earliest reference in this context: "the pillars which Pindar calls the "gates of Gades" when he asserts that they are the farthermost limits reached by Heracles"; the passage in Pindar has not been traced.

- Plato, Critias 133d–114a

- The "testimony of Eusebius" was "drawn from the most ancient historians" according to Mercator. Eusebius' Praeparatio evangelica gives accounts of Atlas that had been translated from the works of ancient Phoenician Sanchuniathon, the original sources for which predate the Trojan War (i.e. 13th century BCE).

- For further comment on Mercator's chosen Titanic genealogy see Keuning (1947), Akerman (1994) and Ramachandran (2015), p. 42

- Mercator & Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection (Library of Congress) (2000)

- See Bibliotheca historica, Book III, Eusebius' Praeparatio evangelica references the same mythology as Diodorus stating "These then are the principal heads of the theology held among the Atlanteans".

- Grafton, Most & Settis (2010), p. 103

- See Gantz (1993), p. 401 and Ogden (2008), p. 47-49

- For instance, the Phoenician Hanno the Navigator is said to have sailed as far as Mount Cameroon in the 5th or 6th century BC. See Lemprière (1833), pp. 249–250 and Ovid, The Metamorphoses, commented by Henry T. Riley ISBN 978-1-4209-3395-6

- Lemprière (1833), pp. 249–250

- Paolo Martini, Il nome etrusco di Atlante, (Rome:Università di Roma) 1987 investigates the etymology of aril, rejecting a link to the verbal morpheme ar- ("support") in favor of a Phoenician etymon in an unattested possible form *'arrab(a), signifying "guarantor in a commercial transaction" with the connotation of "mediator", related to the Latin borrowing arillator, "middleman". This section and note depend on Rex Wallace's review of Martini in Language 65.1 (March 1989:187–188).

- Diodorus Siculus, 4.27.2; Gantz (1993), p. 7.

- Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.21.4, 2.21.6; Ovid, Fasti 5.164

- Hyginus, Fabulae 192

- Hesiod, Works and Days 383; Apollodorus, 3.10.1; Ovid, Fasti 5.79

- Homer, Odyssey 1.52; Apollodorus, Epitome 7.24

- Hyginus, Fabulae 82 & 83

- Pausanias, 8.12.7 & 8.48.6

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface

- Ashley Baynton-Williams. "The "Lafreri school" of Italian mapmakers". Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- van Egmond, Marco. "The 'Atlas' by Mercator and Hondius". Utrecht University. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- Vogel, L. Z.; Savva, Stavroula (1993-12-01). "Atlas personality". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 66 (4): 323–330. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01758.x. ISSN 2044-8341. PMID 8123600.

- "Nautilus Cup". The Walters Art Museum.

- Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- Although usually the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, as in Hesiod, Theogony 371–374, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 507–511, Clymene, one of the Oceanids, the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at Hesiod, Theogony 351, was the mother by Iapetus of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus, while according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, another Oceanid, Asia was their mother by Iapetus.

- According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444–445 n. 2, 446–447 n. 24, 538–539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

References

- Akerman, J. R. (1994). "Atlas, la genèse d'un titre". In Watelet, M. (ed.). Gerardi Mercatoris, Atlas Europae. Antwerp: Bibliothèque des Amis du Fonds Mercator. pp. 15–29.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus (1933–67). Oldfather, C. H.; Sherman, C. L.; Welles, C. B.; Geer, R. M.; Walton, F. R. (eds.). Diodorus of Sicily : The Library of History. 12 Vols (2004 ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Gantz, T. (1993). Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4410-2. LCCN 92026010. OCLC 917033766.

- Grafton, A.; Most, G. W.; Settis, S., eds. (2010). The Classical Tradition (2013 ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07227-5. LCCN 2010019667. OCLC 957010841.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod; Works and Days, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hornblower, S.; Spawforth, A.; Eidinow, E., eds. (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. LCCN 2012009579. OCLC 799019502.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, De Astronomica, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. Online version at ToposText.

- Keuning, J. (1947). "The History of an Atlas: Mercator. Hondius". Imago Mundi. 4 (1): 37–62. doi:10.1080/03085694708591880. ISSN 0308-5694. JSTOR 1149747.

- Lemprière, J. (1833). Anthon, C. (ed.). A Classical Dictionary. New York: G. & C. & H. Carvill [etc.] LCCN 31001224. OCLC 81170896.

- Mercator, G.; Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection (Library of Congress) (2000). Karrow, R. W. (ed.). Atlas sive Cosmographicæ Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura: Duisburg, 1595 (PDF). Translated by Sullivan, D. Oakland, CA: Octavo. ISBN 978-1-891788-26-0. LCCN map55000728. OCLC 48878698. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 March 2016.

- Ogden, D. (2008). Perseus (1st ed.). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42724-1. LCCN 2007031552. OCLC 163604137.

- Ogden, D. (2013). Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955732-5. LCCN 2012277527. OCLC 799069191.

- Ramachandran, A. (2015). The Worldmakers: Global Imagining in Early Modern Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-28879-6. OCLC 930260324.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Atlas"

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. III (9th ed.). 1878. p. 27.

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (c. 120 images of Atlas)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)