Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (Latin: Regnum Italiae),[5] existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

Kingdom of Italy | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 469 (493 in Italy)–553 | |||||||||||||||||||

_white.jpg.webp) Coin depicting Theodoric the Great (475–526)

| |||||||||||||||||||

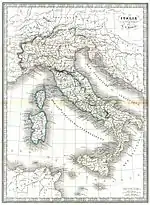

The Ostrogothic Kingdom at its greatest extent. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Ravenna (493 to 540) Pavia (540 to 553) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Gothic, Vulgar Latin | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Official: Arian and Chalcedonian Christianity[1] Minorities: Judaism,[2] Pelagian Christianity,[3] Syncretic Roman paganism,[4] Manichaeism[3] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||

• 493–526 | Theodoric (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

• 552–553 | Teia (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||

• Battles of Isonzo and Verona | 489 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Fall of Ravenna | 469 (493 in Italy) | ||||||||||||||||||

• Start of Gothic War | 535 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 553 | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great killed and replaced Odoacer, a Germanic soldier, erstwhile-leader of the foederati in Northern Italy, and the de facto ruler of Italy, who had deposed the last emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, in 476. Under Theodoric, its first king, the Ostrogothic kingdom reached its zenith, stretching from modern southern France in the west to the modern western Serbia in the southeast. Most of the social institutions of the late Western Roman Empire were preserved during his rule. Theodoric called himself Gothorum Romanorumque rex ("King of the Goths and Romans"), demonstrating his desire to be a leader for both peoples.

Starting in 535, the Byzantine Empire invaded Italy under Justinian I. The Ostrogothic ruler at that time, Witiges, could not defend the kingdom successfully and was finally captured when the capital Ravenna fell. The Ostrogoths rallied around a new leader, Totila, and largely managed to reverse the conquest, but were eventually defeated. The last king of the Ostrogothic Kingdom was Teia.

History

Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths were the eastern branch of the Goths. They settled and established a powerful state in Dacia, but during the late 4th century, they came under the dominion of the Huns. After the collapse of the Hunnic empire in 454, large numbers of Ostrogoths were settled by Emperor Marcian in the Roman province of Pannonia as foederati. Unlike most other foederati formations, the Goths were not absorbed into the structure and traditions of the Roman military but retained a strong identity and cohesion of their own.[6] In 460, during the reign of Leo I, because the payment of annual sums had ceased, they ravaged Illyricum. Peace was concluded in 461, whereby the young Theodoric Amal, son of Theodemir of the Amals, was sent as a hostage to Constantinople, where he received a Roman education.[7]

In previous years, a large number of Goths, first under Aspar and then under Theodoric Strabo, had entered service in the Roman army and were a significant political and military power in the court of Constantinople. The period 477-483 saw a complex three-way struggle among Theodoric the Amal, who had succeeded his father in 474, Theodoric Strabo, and the new Eastern Emperor Zeno. In this conflict, alliances shifted regularly, and large parts of the Balkans were devastated by it.[8]

In the end, after Strabo's death in 481, Zeno came to terms with Theodoric. Parts of Moesia and Dacia ripensis were ceded to the Goths, and Theodoric was named magister militum praesentalis and consul for 484.[8] Barely a year later, Theodoric and Zeno fell out, and again Theodoric's Goths ravaged Thrace. It was then that the thought occurred to Zeno and his advisors to direct Theodoric against another troublesome neighbour of the Empire - the Italian kingdom of Odoacer.

Odoacer's kingdom (476–493)

In 476, Odoacer, leader of the foederati in the West, had staged a coup against the rebellious magister militum Orestes, who was seeking to have his son Romulus Augustulus recognized as Western Emperor in place of Emperor Julius Nepos. Orestes had reneged on the promise of land in Italy for Odoacer's troops, a pledge made to ensure their neutrality in his attack on Nepos. After executing Orestes and putting the teenage usurper in internal exile, Odoacer paid nominal allegiance to Nepos (now in Dalmatia) while effectively operating autonomously, having been raised to the rank of patrician by Zeno. Odoacer retained the Roman administrative system, cooperated actively with the Roman Senate, and his rule was efficient and successful. He evicted the Vandals from Sicily in 477, and in 480 he occupied Dalmatia after the murder of Julius Nepos.[9][10]

Conquest of Italy by the Goths (488–493)

An agreement was reached between Zeno and Theodoric, stipulating that Theodoric, if victorious, was to rule in Italy as the emperor's representative.[11] Theodoric with his people set out from Moesia in the autumn of 488, passed through Dalmatia and crossed the Julian Alps into Italy in late August 489. The first confrontation with the army of Odoacer was at the river Isonzo (the battle of Isonzo) on August 28. Odoacer was defeated and withdrew towards Verona, where a month later another battle was fought, resulting in a bloody, but crushing, Gothic victory.[12]

Odoacer fled to his capital at Ravenna, while the larger part of his army under Tufa surrendered to the Goths. Theodoric then sent Tufa and his men against Odoacer, but he changed his allegiance again and returned to Odoacer. In 490, Odoacer was thus able to campaign against Theodoric, take Milan and Cremona and besiege the main Gothic base at Ticinum (Pavia). At that point, however, the Visigoths intervened, the siege of Ticinum was lifted, and Odoacer was decisively defeated at the river Adda on 11 August 490. Odoacer fled again to Ravenna, while the Senate and many Italian cities declared themselves for Theodoric.[12]

Theodoric kills Odoacer (493)

The Goths now turned to besiege Ravenna, but since they lacked a fleet and the city could be resupplied by sea, the siege could be endured almost indefinitely, despite privations. It was not until 492 that Theodoric was able to procure a fleet and capture Ravenna's harbours, thus entirely cutting off communication with the outside world. The effects of this appeared six months later, when, with the mediation of the city's bishop, negotiations started between the two parties.[13]

An agreement was reached on 25 February 493, whereby the two should divide Italy between them. A banquet was organised in order to celebrate this treaty. It was at this banquet, on March 15, that Theodoric, after making a toast, killed Odoacer with his own hands. A general massacre of Odoacer's soldiers and supporters followed. Theodoric and his Goths were now masters of Italy.[13]

Theodoric's rule

| "... Theodoric was a man of great distinction and of good-will towards all men, and he ruled for thirty-three years. Under his rule, Italy for thirty years enjoyed such good fortune that his successors also inherited peace. For whatever he did was good. He so governed two races at the same time, Romans and Goths, that although he himself was of the Arian sect, he nevertheless made no assault on the Catholic religion; he gave games in the circus and the amphitheatre, so that even by the Romans he was called a Trajan or a Valentinian, whose times he took as a model; and by the Goths, because of his edict, in which he established justice, he was judged to be in all respects their best king." |

| Anonymus Valesianus, Excerpta II 59-60 |

Like Odoacer, Theodoric was ostensibly a patricius and subject of the emperor in Constantinople, acting as his viceroy for Italy, a position recognized by the new Emperor Anastasius in 497. At the same time, he was the king of his own people, who were not Roman citizens. In reality, he acted as an independent ruler, although unlike Odoacer, he meticulously preserved the outward forms of his subordinate position.[14]

The administrative machinery of Odoacer's kingdom, in essence that of the former Empire, was more or less retained by the Ostrogoths. According to the analysis of Jonathan J. Arnold, Theoderic presented himself - and was more or less accepted as - a Roman Emperor.[15] But despite this rhetoric, Italy had undergone significant structural changes in the fifth century, which required that Roman administrative traditions had to be adapted by Theoderic's court.[16] The Senate continued to function normally and was consulted on civil appointments, and the laws of the Empire were still recognized as ruling the Roman population, though Goths were ruled under their own traditional laws. Indeed, as a subordinate ruler, Theodoric did not possess the right to issue his own laws (leges) in the system of Roman law, but merely edicts (edicta), or clarifications on certain details.[14]

The continuity in administration is illustrated by the fact that several senior ministers of Odoacer, like Liberius and Cassiodorus the Elder, were retained in the new kingdom's top positions.[17] The close cooperation between Theodoric and the Roman elite began to break down in later years, especially after the healing of the ecclesiastical rift between Rome and Constantinople (see below), as leading senators conspired with the Emperor. This resulted in the arrest and execution of the magister officiorum Boethius and his father-in-law, Symmachus, in 524.[18]

On the other hand, the army and all military offices remained the exclusive preserve of the Goths. The Goths were settled mostly in northern Italy, and kept themselves largely apart from the Roman population, a tendency reinforced by their different faiths: the Goths were mostly Homoian Christians (''Arians"), while the people they ruled over were adherents of Chalcedonian Christianity.[19] Despite this fact, Theoderic enjoyed good relations with the Roman church, although questions of relative jurisdiction, especially in controversies involving clerics, remained potentially fraught.[20] Jews in Theoderic's kingdom were both disadvantaged and protected as they had been under Roman law, which among other things, provided legal protections for their places of worship.[19] Theodoric's view was clearly expressed in his letters to the Jews of Genoa: "The true mark of civilitas is the observance of law. It is this which makes life in communities possible, and which separates man from the brutes. We therefore gladly accede to your request that all the privileges which the foresight of antiquity conferred upon the Jewish customs shall be renewed to you..."[21] and "We cannot order a religion, because no one can be forced to believe against his will."[22]

Relations with the Germanic states of the West

It is in his foreign policy rather than domestic affairs that Theodoric appeared and acted as an independent ruler. By means of marriage alliances, he sought to establish a central position among the barbarian states of the West. As Jordanes states: "...there was no race left in the western realms which Theodoric had not befriended or brought into subjection during his lifetime."[23] This was in part meant as a defensive measure, and in part as a counterbalance to the influence of the Empire. His daughters were wedded to the Visigothic king Alaric II and the Burgundian prince Sigismund,[24] his sister Amalfrida married the Vandal king Thrasamund,[25] while he himself married Audofleda, sister of the Frankish king Clovis I.[26]

These policies were not always successful in maintaining peace: Theodoric found himself at war with Clovis when the latter attacked the Visigoth dominions in Gaul in 506. The Franks were rapidly successful, killing Alaric in the Battle of Vouillé and subduing Aquitania by 507. However, starting in 508, Theodoric's generals campaigned in Gaul, and were successful in saving Septimania for the Visigoths, as well as extending Ostrogothic rule into southern Gaul (Provence) at the expense of the Burgundians. There in 510 Theodoric reestablished the defunct praetorian prefecture of Gaul. Now Theodoric had a common border with the Visigothic kingdom, where, after Alaric's death, he also ruled as regent of his infant grandson Amalaric.[27]

Family bonds also served little with Sigismund, who as a staunch Chalcedonian Christian cultivated close ties to Constantinople. Theodoric perceived this as a threat and intended to campaign against him, but the Franks acted first and invaded Burgundy in 523, quickly subduing it. Theodoric could only react by expanding his domains in the Provence north of the river Durance up to the Isère.

The peace with the Vandals, secured in 500 with the marriage alliance with Thrasamund, and their common interests as Arian powers against Constantinople, collapsed after Thrasamund's death in 523. His successor Hilderic showed favour to the Nicaean Christians, and when Amalfrida protested, he had her and her entourage murdered. Theodoric was preparing an expedition against him when he died.[28]

Relations with the Empire

| "It behoves us, most clement Emperor, to seek for peace, since there are no causes for anger between us. [...] Our royalty is an imitation of yours, modelled on your good purpose, a copy of the only Empire; and insofar as we follow you do we excel all other nations. Often you have exhorted me to love the senate, to accept cordially the laws of past emperors, to join together in one all the members of Italy. [...] There is moreover that noble sentiment, love for the city of Rome, from which two princes, both of whom govern in her name, should never be disjoined." |

| Letter of Theodoric to Anastasius Cassiodorus, Variae I.1 |

Theodoric's relations with his nominal suzerain, the Eastern Roman Emperor, were always strained, for political as well as for religious reasons. Especially during the reign of Anastasius, these led to several collisions, none of which however escalated into general warfare. In 504-505, Theodoric's forces launched a campaign to recover Pannonia and the strategically important town of Sirmium, formerly parts of the praetorian prefecture of Italy, which were now occupied by the Gepids.[29]

The campaign was successful, but it also led to a brief conflict with imperial troops, where the Goths and their allies were victorious. Domestically, the Acacian schism between the patriarchates of Rome and Constantinople, caused by imperial support for the Henotikon, as well as Anastasius' Monophysite beliefs, played into Theodoric's hands, since the clergy and the Roman aristocracy of Italy, headed by Pope Symmachus, vigorously opposed them.[29]

Thus, for a time, Theodoric could count on their support. The war between the Franks and Visigoths led to renewed friction between Theodoric and the Emperor, as Clovis successfully portrayed himself as the champion of the Western Church against the "heretical" Arian Goths, gaining the Emperor's support. This even led to the dispatch of a fleet by Anastasius in 508, which ravaged the coasts of Apulia.[29]

With the ascension of Justin I in 518, a more harmonious relationship seemed to be restored. Eutharic, Theodoric's son-in-law and designated successor, was appointed consul for the year 519, while in 522, to celebrate the healing of the Acacian schism, Justin allowed both consuls to be appointed by Theodoric.[30] Soon, however, renewed tension would result from Justin's anti-Arian legislation, and tensions grew between the Goths and the Senate, whose members, as Chalcedonians, now shifted their support to the Emperor.[31]

The suspicions of Theodoric were confirmed by the interception of compromising letters between leading senators and Constantinople, which led to the imprisonment and execution of Boethius in 524. Pope John I was sent to Constantinople to mediate on the Arians' behalf, and, although he achieved his mission, on his return he was imprisoned and died shortly after. These events further stirred popular sentiment against the Goths.[31]

Death of Theodoric and dynastic disputes (526–535)

24.jpg.webp)

After the death of Theodoric on 30 August 526, his achievements began to collapse. Since Eutharic had died in 523, Theodoric was succeeded by his infant grandson Athalaric, supervised by his mother, Amalasuntha, as regent. The lack of a strong heir caused the network of alliances that surrounded the Ostrogothic state to disintegrate: the Visigothic kingdom regained its autonomy under Amalaric, the relations with the Vandals turned increasingly hostile, and the Franks embarked again on expansion, subduing the Thuringians and the Burgundians and almost evicting the Visigoths from their last holdings in southern Gaul.[32] The position of predominance which the Ostrogothic Kingdom had enjoyed under Theodoric in the West now passed irrevocably to the Franks.

This dangerous external climate was exacerbated by the regency's weak domestic position. Amalasuntha was Roman-educated and intended to continue her father's policies of conciliation between Goths and Romans. To that end, she actively courted the support of the Senate and the newly ascended Emperor Justinian I, even providing him with bases in Sicily during the Vandalic War. However, these ideas did not find much favour with the Gothic nobles, who in addition resented being ruled by a woman. They protested when she resolved to give her son a Roman education, preferring that Athalaric be raised as a warrior. She was forced to discharge his Roman tutors, but instead Athalaric turned to a life of dissipation and excess, which would send him to a premature death.[33]

| "[Amalasuntha] feared she might be despised by the Goths on account of the weakness of her sex. So after much thought she decided [...] to summon her cousin Theodahad from Tuscany, where he led a retired life at home, and thus she established him on the throne. But he was unmindful of their kinship and, after a little time, had her taken from the palace at Ravenna to an island of the Bulsinian lake where he kept her in exile. After spending a very few days there in sorrow, she was strangled in the bath by his hirelings." |

| Jordanes, Getica 306 |

Eventually, a conspiracy started among the Goths to overthrow her. Amalasuntha resolved to move against them, but as a precaution, she also made preparations to flee to Constantinople, and even wrote to Justinian asking for protection. In the event she managed to execute the three leading conspirators, and her position remained relatively secure until, in 533, Athalaric's health began to seriously decline.[34]

Amalasuntha then turned for support to her only relative, her cousin Theodahad, while at the same time sending ambassadors to Justinian and proposing to cede Italy to him. Justinian indeed sent an able agent of his, Peter of Thessalonica, to carry out the negotiations, but before he had even crossed into Italy, Athalaric had died (on 2 October 534), Amalasuntha had crowned Theodahad as king in an effort to secure his support, and he had deposed and imprisoned her. Theodahad, who was of a peaceful disposition, immediately sent envoys to announce his ascension to Justinian and to reassure him of Amalasuntha's safety.[34]

Justinian immediately reacted by offering his support to the deposed queen, but in early May 535, she was executed.[a] This crime served as a perfect pretext for Justinian, fresh from his forces' victory over the Vandals, to invade the Gothic realm in retaliation.[35] Theodahad tried to prevent the war, sending his envoys to Constantinople, but Justinian was already resolved to reclaim Italy. Only by renouncing his throne in the Empire's favour could Theodahad hope to avert war.

Gothic War and end of the Ostrogothic Kingdom (535–554)

The Gothic War between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Ostrogothic Kingdom was fought from 535 until 554 in Italy, Dalmatia, Sardinia, Sicily and Corsica. It is commonly divided into two phases. The first phase lasted from 535 to 540 and ended with the fall of Ravenna and the apparent reconquest of Italy by the Byzantines. With the fall of Ravenna, the capital of the kingdom was brought to Pavia, which it became the last centres of Ostrogothic resistance that continued the war and opposed Eastern Roman rule.[36][37]

During the second phase (540/541–553), Gothic resistance was reinvigorated under Totila and put down only after a long struggle by Narses, who also repelled the 554 invasion by the Franks and Alamanni. In the same year, Justinian promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction which prescribed Italy's new government. Several cities in northern Italy continued to hold out, however, until the early 560s.

The war had its roots in the ambition of Justinian to recover the provinces of the former Western Roman Empire, which had been lost to invading barbarian tribes in the previous century (the Migration Period). By the end of the conflict Italy was devastated and considerably depopulated. As a consequence, the victorious Byzantines found themselves unable to resist the invasion of the Lombards in 568, which resulted in the loss of large parts of the Italian peninsula.

List of kings

- Valamir –465

- Theodemir 470–475

- Theodoric the Great (Thiudoric) 489–526

- Athalaric (Atthalaric) 526–534

- Amalasuintha 534-535

- Theodahad (Thiudahad) 534–536

- Witiges (Wittigeis) 536–540

- Ildibad (Hildibad) 540–541

- Eraric the Rugian (Heraric, Ariaric) 541

- Totila (Baduila) 541–552

- Teia (Theia, Teja) 552–553

Culture

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

Because of the kingdom's short history, no fusion of the two peoples and their art was achieved. However, under the patronage of Theodoric and Amalasuntha, large-scale restoration of ancient Roman buildings was undertaken, and the tradition of Roman civic architecture continued. In Ravenna, new churches and monumental buildings were erected, several of which survive.

The Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, its baptistry, and the Archiepiscopal Chapel follow the typical late Roman architectural and decorative motifs, but the Mausoleum of Theodoric displays purely Gothic elements, such as its construction not from the usual brick, but of massive slabs of Istrian limestone, or the 300-ton single-piece roof stone.

Literature

Some older works were copied in Greek and Gothic (e.g. the Codex Argenteus), and the literature is solidly in the Greco-Roman tradition. Cassiodorus, hailing from a distinguished background, and himself entrusted with high offices (consul and magister officiorum) represents the Roman ruling class. Like many others of his background, he served Theodoric and his heirs loyally and well, something expressed in the writings of the period.

In his Chronica, used later by Jordanes in his Getica, as well as in the various panegyrics written by him and other prominent Romans of the time for the Gothic kings, Roman literary and historical tradition is put in the service of their Gothic overlords. His privileged position enabled him to compile the Variae Epistolae, a collection of state correspondence, which gives great insight into the inner workings of the Gothic state. Boethius is another prominent figure of the period. Well-educated and also from a distinguished family, he wrote works on mathematics, music and philosophy. His most famous work, Consolatio philosophiae, was written while imprisoned on charges of treason.

In Germanic languages, King Theodoric inspired countless legends of questionable veracity.

In popular culture

- The 1876 historical novel A Struggle for Rome by Felix Dahn (and its two-part screen adaptation in 1968 and 1969) focuses on the struggle among the Byzantines, the Ostrogoths and the native Italians over control of Italy after Theodoric's death.

- The 1938 historical novel Count Belisarius by Robert Graves describes the campaigns of the Byzantine general Belisarius to conquer the Ostrogothic Kingdom during the reign of Justinian.

- In the 1941 alternate history novel Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp, a modern archaeologist is transported through time to Ostrogothic Italy, helps to stabilise it after Theodoric's death, and averts its conquest by Justinian.

- Guy Gavriel Kay's Sarantine Mosaic series takes place in a setting based on Ostrogothic Italy and the East Roman Empire, just before the Gothic War.

- Gary Jennings' 1993 novel Raptor documents the rise of Theodoric the Great and the Ostrogothic Kingdom through the eyes of a fictional hermaphrodite Thorn.

Footnotes

^ a: The exact date and circumstances surrounding Amalasuntha's execution remain a mystery. In his Secret History, Procopius proposes that Empress Theodora might have had a hand in the affair, wishing to get rid of a potential rival. Although it is generally dismissed by historians such as Gibbon and Charles Diehl, Bury (Ch. XVIII, pp. 165-167) considers that the story is corroborated by circumstantial evidence.

References

- Cohen (2016), pp. 510–521.

- Cohen (2016), pp. 504–510.

- Cohen (2016), pp. 523, 524.

- Cohen (2016), pp. 521–523.

- Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator, Variae, Lib. II., XLI. Luduin regi Francorum Theodericus rex.

- Chris Wickham, The Inheritance of Rome, 98

- Jordanes, Getica, 271

- Bury (1923), Ch. XII, pp. 413-421.

- "At this time, Odovacar overcame and killed Odiva in Dalmatia", Cassiodorus, Chronica 1309, s.a.481

- Bury (1923), Ch. XII, pp. 406-412.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XII, p. 422.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XII, pp. 422-424.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XII, pp. 454-455.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XIII, pp. 422-424.

- Arnold, Jonathan J. (2014). Theoderic and the Roman Imperial Restoration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107294271. ISBN 978-1-107-05440-0.

- Bjornlie, M. Shane; M. Shane Bjornlie; Kristina Sessa (2016-01-01). "Governmental Administration". In J. J. Arnold (ed.). A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy. Brill. pp. 48–49. doi:10.1163/9789004315938_004. hdl:2027/mdp.39015003846675. ISBN 978-90-04-31593-8.

- Bury (1923), Vol. II, Ch. XIII, p. 458.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, pp. 153-155.

- Cohen (2016), pp. 505–506.

- Cohen, Samuel (February 2022). "Gelasius and the Ostrogoths: jurisdiction and religious community in late fifth‐century Italy". Early Medieval Europe. 30 (1): 20–44. doi:10.1111/emed.12519. ISSN 0963-9462. S2CID 247674196.

- Cassiodorus, Variae, IV.33

- Cassiodorus, Variae, II.27

- Jordanes, Getica 303

- Jordanes, Getica, 297

- Jordanes, Getica, 299

- Bury (1923), Ch. XIII, pp. 461-462.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XIII, p. 462.

- Procopius, De Bello Vandalico I.VIII.11-14

- Bury (1923), Ch. XIII, p. 464.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, pp. 152-153.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, p. 157.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, p. 161.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, pp. 159-160.

- Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, pp. 163-164.

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.V.1

- Thompson, Edward Arthur (1982). Romans and Barbarians: Decline of the Western Empire. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9780299087005.

- "Pavia Royal town". Monasteri Imperiali Pavia. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

Sources

Primary sources

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico, Volumes I-IV

- Jordanes, De origine actibusque Getarum ("The Origin and Deeds of the Goths"), translated by Charles C. Mierow.

- Cassiodorus, Chronica

- Cassiodorus, Varia epistolae ("Letters"), at the Project Gutenberg

- Anonymus Valesianus, Excerpta, Pars II

Secondary sources

- Amory, Patrick (2003). People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52635-7.

- Arnold, Jonathan J. (2014). Theoderic and the Roman Imperial Restoration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107294271. ISBN 978-1-107-05440-0.

- Barnwell, P. S. (1992). Emperor, Prefects & Kings: The Roman West, 395-565. UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2071-1.

- Burns, Thomas S. (1984). A History of the Ostrogoths. Boomington.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1923). History of the Later Roman Empire Vols. I & II. Macmillan & Co., Ltd.

- Cohen, Samuel (2016). "Religious Diversity". In Jonathan J. Arnold; M. Shane Bjornlie; Kristina Sessa (eds.). A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy. Leiden, Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 503–532. ISBN 978-9004-31376-7.

- Gibbon, Edward. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. IV.. Chapters 41 & 43

- Heather, Peter (1998). The Goths. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-20932-4.

- Wolfram, Herwig; Dunlap, Thomas (1997). The Roman Empire and its Germanic peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08511-4.

External links

Media related to Ostrogothic Italy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ostrogothic Italy at Wikimedia Commons